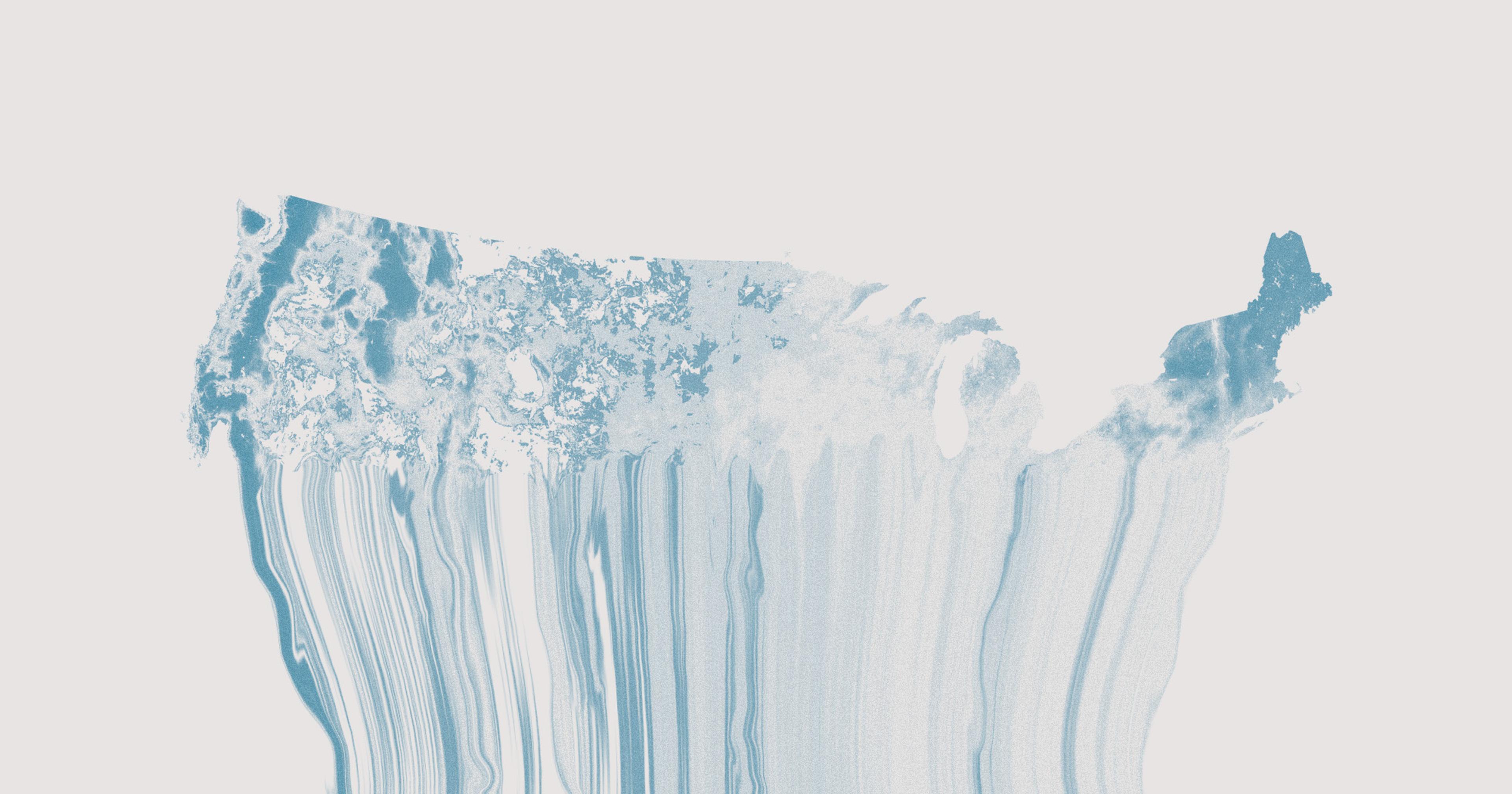

As climate change intensifies, contamination from floods can pose hazards long after the waters recede.

This spring in King County, California, Dusty Ference watched the weather forecast in fascinated horror. First, a series of atmospheric rivers dumped rain. Then, record snowpack in the Sierra Nevada mountains began to melt.

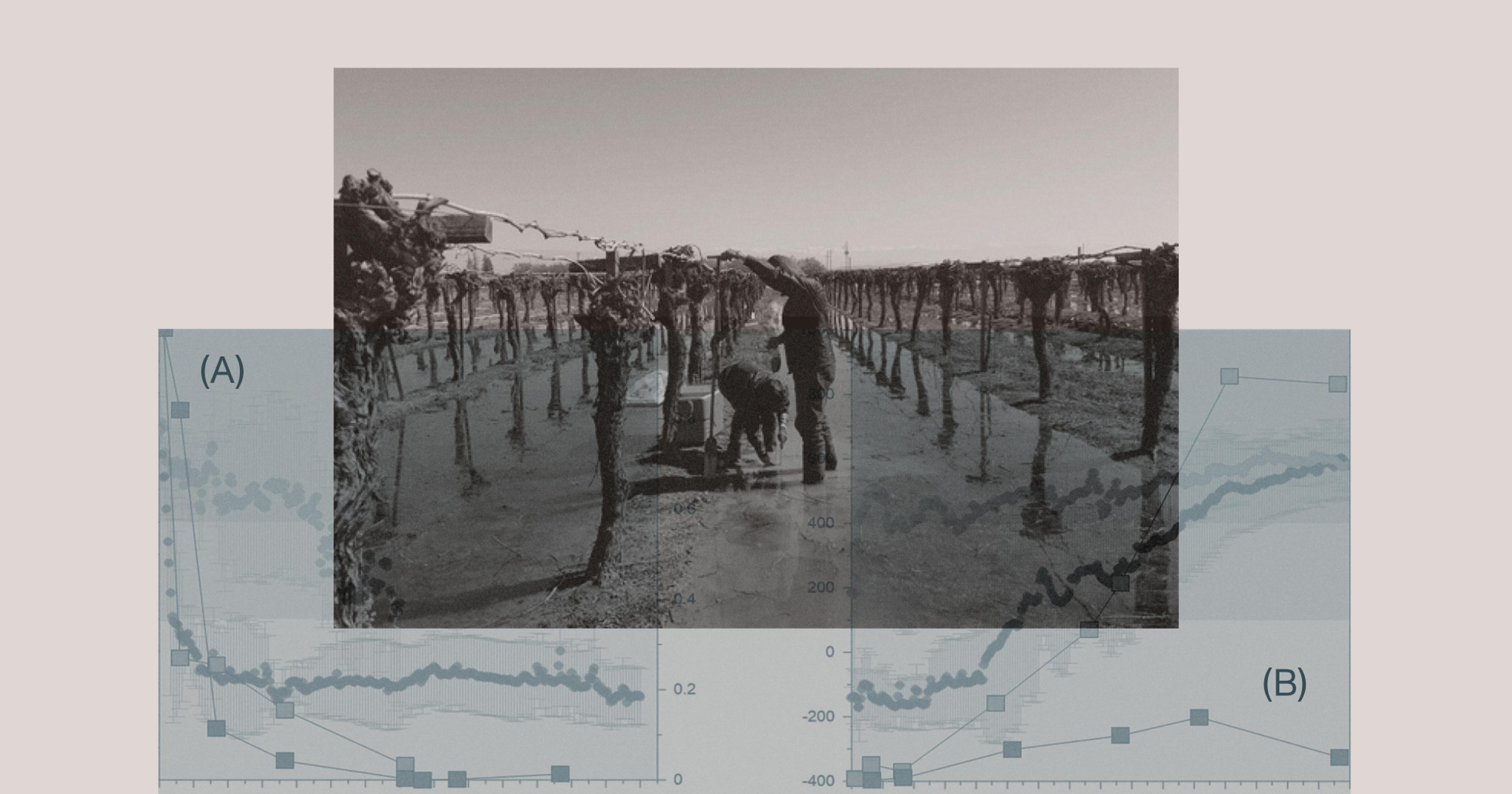

The waters quickly overtopped dams and surged past levees. “It was wild,” Ferrence said, “unlike anything I’ve ever seen.” Every day to get to his job as the executive director of the King County Farm Bureau, he had to cross a rushing creek, keeping a change of clothes and emergency supplies in his pickup in case he couldn’t get home again. The massive flood soon covered more than 90,000 acres of farmland as Tulare Lake refilled.

Tulare was once the largest freshwater body of water west of the Mississippi River. But for decades, it’s been dammed and drained and planted, as the former lakebed grew to support a $2 billion dollar agricultural industry. Now that it’s back, the water isn’t likely to recede anytime soon. “Probably it’ll be a minimum of a year from now before the lake is dry,” Ference said. There’ve been at least $140 million dollars in direct losses of crops like winter wheat and alfalfa so far — but those impacts will be compounded over the summer, as farmers would normally have planted what is now a turgid lake.

The water itself is also now contaminated. In addition to fertilizer and pesticide runoff, floodwaters are often tainted with fecal waste from nearby commercial animal operations, along with parasites and antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pathogens, said Anne Schechinger, agriculture economist and Midwest director at Environmental Working Group. Last year, Schechinger analyzed factory farms in North Carolina, finding many of the large facilities operate in flood plains like Tulare Lake. She said flooding near these kinds of animal operations risks unleashing health hazards like manure and carcasses.

In California’s Central Valley, this year’s deluge will likely exacerbate what was already a widespread problem. “There’s a lot of debris, there’s a lot of agriculture, and agriculture leaches a lot of nitrate into local aquifers,” said Angel Fernandez-Bou, a climate scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists who focuses on sustainable land use. Exposure can cause health effects like blue baby syndrome, a condition that can lead to suffocation, and has also been linked to preterm births and cancer. According to the United States Geological Survey, nitrates can persist for decades, accumulating over time.

Nitrogen and phosphorus runoff from farm fields can also cause algal blooms to explode. “These algae blooms can be toxic,” said Schechinger, “and once it gets into the water, it’s really hard to remove.” In Toledo, Ohio, for example, a cyanobacteria bloom — which can cause vomiting, nausea, and serious neurological problems — tainted the water supply for half a million people in 2014.

“There’s a lot of agriculture, and agriculture leaches a lot of nitrate into local aquifers.”

Near Tulare, the extent of the current nitrate contamination is difficult to determine, as many in the region rely on domestic wells for their drinking water, which are less frequently monitored than municipal drinking sources. But in a 2012 survey, about one in 10 water samples from wells in the Tulare Lake basin exceeded the drinking water nitrate standard.

When the nearby San Joaquin Valley flooded this spring, Fernandez-Bou said, you didn’t need expensive testing to know there was a problem. “The smell was horrible,” he said — especially around the dairies without covered waste ponds. “It’s kind of a disaster now, because agriculture has disturbed everything so much. The region has lost its natural resilience to cope with these extremes.”

Across the country, flooding events like these — as well as drought — are becoming more common, as climate change disrupts weather patterns. That’s a problem for farmers of all scales, said Grace Oedel, the executive director of the Northeast Organic Farming Association, Vermont (NOFA-VT). After parts of the state recently saw 9 inches of rain in 24 hours, she said growers are reeling. “Floodplain is good soil to farm in,” she said. “That’s where great farming has happened historically, is along rivers.” That’s because water channels meander over time, depositing fertile soil. But Vermont has now seen multiple 100-year floods within the last five years. “What is the frequency with which we can tolerate this amount of flooding, and continue to farm on floodplains?”

Oedel is also concerned about the possibility of contamination. She said that soil tests are now available from the state for free, but testing doesn’t actually help farmers get back into the field. “What happens if you learn there is contamination?” she asked. “What is the plan?” In Maine, for instance, the discovery of PFAS in water and soil last year permanently shut down multiple farms; the owners were not adequately compensated for their lost livelihoods. What happens to support farms that face issues is an important question, she said. “Any fallout from the flood isn’t an individual farm problem, it’s a collective problem.”

“The region has lost its natural resilience to cope with these extremes.”

Research from the American Farm Bureau Federation suggests that nationwide, disasters caused $21.5 billion dollars in crop losses last year. Only half of those were insured. There may never be a good time of year to have a flood, but Vermont’s rains came at a particularly bad time: In early July, many farmers have heavily invested in their season, but have yet to harvest. Now, Oedel said, “they are deeply in debt.” Even before the floods, many of Vermont’s farmers were already struggling.

Those departures translate into the upheaval of families and communities, said Ference. In King County, for example, farmers hoping to wait out the water will have to rely on savings. “We don’t have another industry,” he said. “You can’t just go to town and find another job.” Farmworkers, many of whom are seasonal employees, face even steeper challenges. The majority are undocumented, and their housing is often tied to their job, making it more difficult to access resources like disaster assistance or unemployment insurance. “The work conditions are often very precarious,” Fernandez-Bou said.

The increasingly erratic weather makes it crucial to refine strategies for supporting farmers during floods. Last year, the Farm Service Agency announced a new emergency relief program to help offset these kinds of losses, but it is targeted at commodity and specialty growers, not the small-scale farms that NOFA-VT works with in New England.

In the meantime, crises abound. Shortly before the flood, Odel was helping growers navigate the wildfire smoke from Canada. “Now our food is underwater, and the water itself is polluted with runoff,” she said. “The government needs to understand that they need to adapt much more quickly to the reality that we’re living in — which is a very intense, ongoing climate crisis.”