The USDA has thrown $300 million at organic agriculture. Is that enough to save our soil?

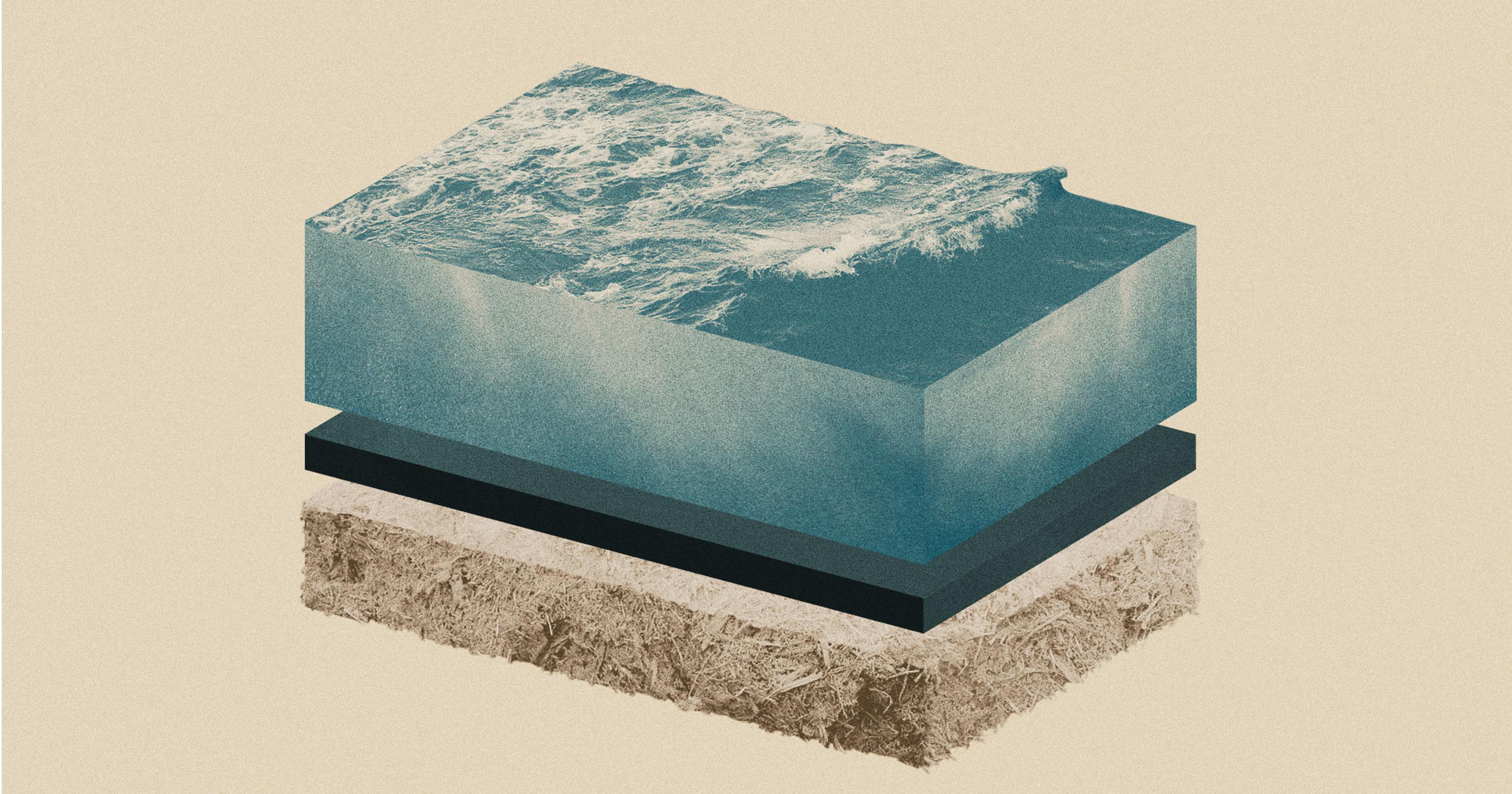

Last July was the second wettest on record in eastern Massachusetts, conditions that can leave fields farmed with chemicals all swampy and pocked with puddles. But despite the dumping of more than 10 inches of rain, the fields at Long Life Farms in Hopkinton were puddle-free. All that delicious moisture was soaked up by 2.5 acres of thriving soil, packed with microorganisms and nutrients that vegetable farmer Laura Davis has painstakingly cultivated over a decade to maintain the farm’s organic status.

The soil at Long Life owes its sponginess to a number of factors: For starters, Davis doesn’t till the land. She lets the soil absorb nutrients undisturbed. Over her vegetables, she grows a canopy of cover crops that photosynthesize year-round to keep the microbes in the dirt busy. And she rotates the veggies around her fields to naturally deter pests — growing napa cabbage in one field this season, then relocating it for the next — allowing her to skip the pesticide sprays that kill good bacteria and fungi, what she calls “the little farmers beneath your feet.”

Though the modern organic movement has its roots in the humble “back-to-the-land” days of the 1970s, it’s now globally recognized. Davis works with the Northeast Organic Farmers Association (NOFA), an organic advocacy group that pushed the federal government to establish nationwide standards for organic farming in the early 2000s.

Since then, with greater visibility into conventional agriculture’s reliance on synthetics, consumer demand for organic products has grown exponentially — and far outpaced the number of organic farms in the U.S., which only account for 1% of the country’s total farmland. This has the potential to change, however, with a new and unprecedented investment from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). The Organic Transition Initiative is a multi-pronged program with $300 million in funding, designed to address the challenges growers face as they transition away from conventional, mechanized agriculture.

Those challenges are many, and the upfront costs of switching to organic have historically deterred farmers who are hamstrung by already thin margins. Some small organic farms forgo the lengthy certification, operating instead on their customers’ trust. But because of climate change, it’s never been more critical to adopt organic methods on a massive scale: Among other benefits, healthy soil promotes biodiversity, stores more carbon, is more resilient in droughts and floods, and is more resistant to erosion.

Though it can be a moneymaker for farmers in the long-run (organic products earn more at the market, and growers can reallocate the money they once spent on fertilizers and sprays), some see it as a risk — particularly those currently producing large yields of genetically modified crops. Organic farming is especially labor intensive, and USDA certification takes time: Soil needs to be synthetics-free for a minimum of three years before a grower can apply. That transition process sometimes has major hurdles, like how some newly transitioned organic farms may actually push neighboring farms to employ more pesticides to handle the uptick in bug activity, according to a new study.

Matthew Dillon, co-CEO of the Organic Trade Association, said organic farmers face other obstacles including lack of support in weed management, soil fertility, and crop insurance. Some row crop may want to grow organic, for instance, but the nearest certified organic grain elevator — where grains can be stored without non-organic cross-contamination — is hundreds of miles away. This new funding stream from the USDA is primed to solve those and similar problems, he said.

“The system of finance that we have in this country doesn’t have the support for that transition.”

The office of the USDA’s Farm Service Agency echoed enthusiasm for the program, adding that it provides an opportunity to ensure BIPOC farmers have equal access to organic farming and its benefits. Zach Ducheneaux, a cattle rancher from South Dakota and the first Native American to be appointed Administrator of the Farm Service Agency, blames the structure of farm programs since the 1930s for having barred the “generational accumulation of wealth that would allow underserved producers to be fully participating stakeholders” in the organic movement. To properly address that gap, he said, any new USDA initiative needs to prioritize equity.

In that spirit, the USDA money isn’t all funneled directly into fields; chunks of it have gone to community-building efforts like paid mentorship programs that pair experienced organic farmers with those new to organic farming or to farming altogether, and regional groups including NOFA now host regular BIPOC skill-sharing and networking events to boost diverse participation.

Many would argue the large-scale transition to organic is long overdue. But some critics of the USDA worry that organic standards have been so watered down that they’ve lost their meaning, making this effort yet another toothless attempt at sustainability. A major rift in the movement came when the USDA started awarding organic certification to hydroponic farms, which grow crops in an artificial water-based solution instead of soil.

Advocates from groups like the Real Organic Project in New England, including Davis, have protested this development, noting that soil health is the backbone of organic growing. Davis said there’s fear among many soil-based organic farmers that organic-certified hydroponics, which require a fraction of the labor, will put them out of business. The waning trust in “organic” certification has pushed many for a more rigid “regenerative” label, though there aren’t yet nationwide standards for regenerative growing.

Still, Davis stressed, when done with integrity, organic agriculture is regenerative.

She also believes there’s plenty more work to be done. For starters, she wants to see cover crops subsidized in the next Farm Bill. Davis grew up in Illinois and still has an uncle out there who runs a 2,500-acre corn and soybean farm. Like lots of comparable large-scale operations, her uncle’s farm is not organic. He doesn’t plant cover crops. Come winter, his fields are barren and his soil is dormant, making him more vulnerable to the climate change-induced drought that has gripped much of the Midwest in recent years, even threatening another Dust Bowl.

The waning trust in “organic” certification has pushed many for a more rigid “regenerative” label.

Given how much cash Davis has spent on cover crops for her tiny 2.5-acre plot, she knows it would cost her uncle tens of thousands of dollars to make the transition — an investment few business people would be willing to make without an air-tight profit guarantee.

To Ducheneaux, it’s obvious that organic farming is pragmatic farming. But the current financial structure of the agriculture sector forces farmers to opt for Band-aids instead of real well-being. Cover crops aren’t always cash crops. Microbes don’t grow big and ripe on vines like a tomato. It’s hard to make good choices when your vision is obstructed by the bottom line.

“The notion that producers don’t want to produce healthier food that is better for the environment and soil health is at best some type of logical fallacy,” Ducheneaux said. “It behooves producers to engage in things that can increase their productivity and their sale price. But the system of finance that we have in this country doesn’t have the support for that transition.”

Federal subsidies can give farmers the leeway they need to be more pragmatic — much like Ducheneaux’s predecessors before the arrival of Europeans. “We understood microbial action,” he said of his Cheyenne River Sioux ancestors. “We couldn’t see it. But that didn’t mean we didn’t understand it.”

Given time, however, the benefits of organic farming do actually bloom beautifully into sight. Start with just a small plot, Davis said, and eventually the soil will wriggle to life full of earthworms, beetles, and bugs — all signs that big things are happening underground.

Disclosure: NOFA-NJ, NOFA’s New Jersey arm, is one of Ambrook‘s customers.