As bison makes slow and steady gains in the market, fractures over the future of the industry emerge.

When two competitors enter a market, it’s natural that they’re going to have much more in common than what makes them different. But some rivalries, like bison and beef, cannot be squarely compared, apples to apples, because their differences start biologically.

Bison remain partially wild animals, whereas most cattle are fully domesticated apart from some wayward herds in the American West. Bison can wander through all types of terrain and withstand inclement weather because they’re native to North America, developed over millennia to live all across the continent. They can independently give birth, so with enough land, a bison rancher can own a herd and be relatively hands off with their animals while they wander off. When bison eat, they’re drawn to native grasses and leave flowers and clover alone, which can support butterflies and other pollinators in the surrounding ecosystem. Due to these factors, bison is a very tender, lean protein that many describe as slightly sweet.

Cattle, on the other hand, were introduced here in the 15th century and cannot naturally traverse different types of terrain, so they tend to congregate on flat land near waterways (which can have adverse effects on local water sources). Due to the current scale and set-up of the beef industry, cattle require a significant amount of hands-on action with ranchers to house, feed, and assist with the birthing of animals. They also tend to be crowded very densely when they’re outside, and if given the choice, will indiscriminately consume flowers, clover, and native grasses that can limit pollinators.

Some estimates say that prior to the arrival of European settlers in North America, 75 million bison roamed the continent from coast to coast. But by the late 1800s, the massive bison herds were brought to the brink of extinction with less than 500 head. The mass killings were partly for the value of their hides and bones for fertilizer, to build infrastructure for incoming settlers, and to wreak havoc against nomadic Western tribes to pressure them onto reservations. Native tribes not only subsisted on the animal, but used each and every part of it for toys, shelter, clothing, and tools. Without buffalo to hunt, a way of life was gone.

But there has been major revitalization in recent years of Tribal bison ranching programs, including a 2023 initiative by the USDA to buy bison meat from a handful of Native tribes to provide a traditional food option via the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations. Thus, the bison market also supports Native ranchers and vendors in a particularly unique way.

Yet despite the national heritage, appeal, and ecological benefits of bison, it’s still not eaten in quantities that get anywhere near beef. It makes one wonder: Why?

A Burgeoning Meat Market

“In modern times, consumer consumption is relatively new,” said Jim Matheson, executive director of the National Bison Association, a coalition of about 1,100 bison ranchers, producers, and marketers.

Matheson cites the birth of the commercial bison industry in the U.S. as February 1966 when Custer State Park in South Dakota hosted the first live buffalo auction. One hundred animals were sold off to manage the growing herd, and buyers considered the possibilities of buying and raising bison for meat consumption. Within 30 years, the industry soared due to interest from enthusiasts like Ted Turner.

“The live market got really active in the 1990s for processing animals, but there was no meat market,” said Matheson. By 2000, a massive crash brought the bison market down to the point where animals that days before went for $10,000 apiece fell to a measly $200.

That’s when the National Bison Association got very serious about developing a sustainable market that would support the entire supply chain for years to come — as opposed to a bubble without actual market support from consumers.

“In modern times, consumer consumption is relatively new.”

Terry Kremeniuk, previous executive director of the Canadian Bison Association in Saskatchewan, Canada, also describes bison as a niche protein in the mainstream Canadian market, except the industry didn’t get its start until between 1980 and 1985. In 1996, the first year that a census of bison was taken, there were 45,000 head total in Canada, but the majority of animals raised in Canada were slaughtered and sold in the U.S. (This remains true.)

Even so, the smaller scale of bison inhibits it from getting anywhere close to the market for beef. Last year about 85,000 bison were processed for meat consumption stateside, Matheson said. Beef, on the other hand, saw 36 million head processed. Thus, Matheson argues that based on assessment and conversations with ranchers, processors, and restaurants, there is not enough bison to meet current American demand, especially after the pandemic. This is why the U.S. remains such a strong import market for Canadian bison.

The bison contraction is related to the same pinch right now in the beef industry: Farmers and ranchers are reducing their herd size due to drought and rising operating costs, so cattle inventory is at a 50-year low. Therefore, the price of beef is skyrocketing, which makes the choice between a $10 pound of ground bison much more approachable when beef is now $7 or $8. The average price per pound of bison meat, Matheson said, has stayed consistent for some time, unlike beef.

But Kremeniuk said that contrary to Matheson’s assessment, there isn’t exactly a shortage of bison, but still plenty of room for more growth and expansion, especially for specialty products.

“There’s certainly room for more demand,” he said.

Alternate Harvesting

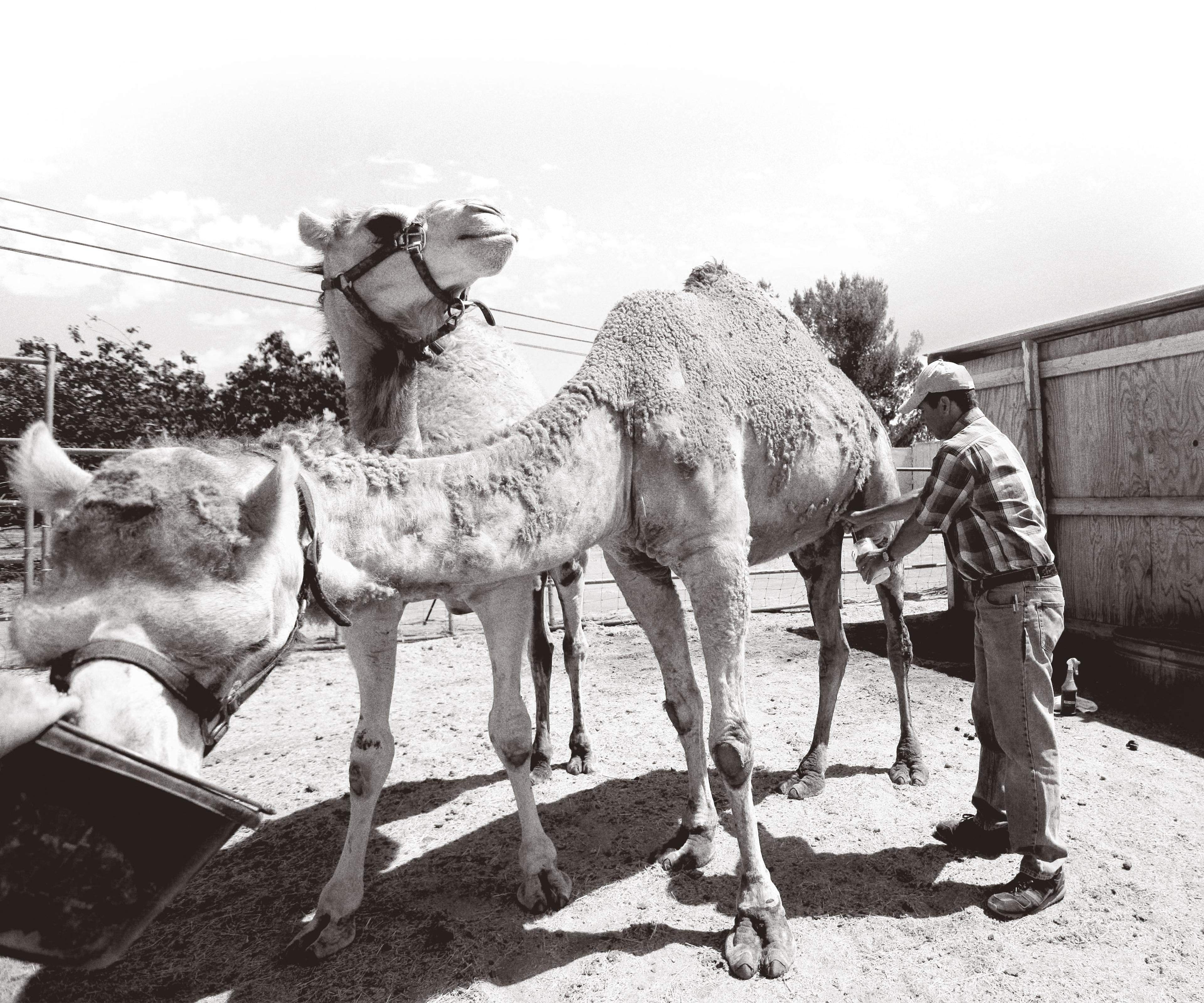

Colton and Jilian Jones, owner-operators of Wild Idea Buffalo Company in South Dakota, are niche processors in the larger bison industry. What distinguishes their business is field harvesting all their bison, which means that an animal is born, raised, and lives their life in the wide open plains. When it is time for slaughter, a hunter drives out to their pasture and kills them with a pop-up slaughterhouse via semi-truck stationed nearby.

This model is distinct in a market where between 92 to 95 percent of bison available in stores, the couple said, are finished on feedlots in a similar fashion to beef for the last few months of their life. Due to this, some experts argue that bison is not a fully wild animal anymore, but somewhat domesticated due to human intervention.

With field harvesting, every animal lives and dies without seeing the inside of a truck, feedlot, or slaughterhouse. The method also ensures that each animal lives a life with zero human intervention until death.

However, it drives costs up: A pound of Wild Idea’s ground bison is about $16.50. Both Jilian and Colton say that they don’t see beef as their competition whatsoever; they’re competing with the larger bison market that uses similar practices as the cattle industry — but still trade on the environmental, cultural, and ecological legacy of bison.

“It’s whitewashing,” said Colton. “[That’s] grain-finished buffalo … [When a customer shops and] thinks of a buffalo, they put the animal in a prairie landscape. They don’t think of a buffalo and a feedlot.”

“When a customer shops and thinks of a buffalo, they put the animal in a prairie landscape. They don’t think of a buffalo and a feedlot.”

Colton sees the course changing for his niche corner of the industry only if other producers actively compete with them to raise buffalo in wide-open landscapes and field harvest themselves. But it’s still a chicken and the egg scenario — in order for ranchers to take on more bison, the market for more expensive specialty field harvested meat has to grow.

But for Matheson and Kremeniuk, this simply isn’t doable when the wider industry is still so young and trying to sustainably grow amidst a wide range of ranchers and processors.

Kremeniuk said that people who produce bison want to earn the highest returns, and to grow the industry, it needs to continue to be profitable. The way that the cards fall right now with the exchange rate between CAD and USD and the low cost of shipping animals to the U.S., if something were to change, it could result in the Canadian market growing and a greater share of bison being kept at home where it is raised.

The flipside is that this comes with its own risks, and ceilings. The American market is 334 million people strong and the darling of any global business seeking to grow and succeed with an economy of scale. Canada, on the other hand, has about 40 million citizens, and if bison were kept at home, the bison marketing and sales would have to ramp up significantly to make up for the American export losses. Such pressures, if all didn’t pan out, could force Canadian ranchers to throw in the towel on managing their own herds.

Looking Ahead

Matheson doesn’t have dreams of grandeur when it comes to bison burgers or the like becoming wholly mainstream, even for the sake of climate change. Instead, he envisions slow, steady growth in the years to come that reflects how the bison market has organically grown on its own without excessive inputs — much like the animal itself.

“I know what we’re doing is working, and supporting tribal buffalo preservation,” he said. “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Colton of Wild Idea says that while he’d like to see a shift in harvesting practices, he’s been heartened to see the growing interest in the concept.

“It’s catching traction … In the last year or two, more people are asking if they can hire us for field harvesting, or how to make a mobile harvester,” Colton said. “There’s definitely movement in our area.”

Meanwhile Kremeniuk said that all things considered, it’s important to have perspective on where the state of bison as an animal was in the not-so-distant past, and how far the species has come partly due to more people choosing it as the grocery store — no matter the method of harvest.

“To look now at where the industry was in the 1800s and the number of bison down from millions to hundreds,“ said Kremeniuk, ”it’s one of the best conservation stories of our time.”