The federal government created an uproar by slaughtering New Mexico’s “feral” cattle via helicopter. Ranchers and animal advocates aren’t happy, but disagree on the best path forward.

As we’ve previously reported, the U.S. government is shooting cattle from the air and leaving the meat to rot.

In February, a New Mexico District Judge granted the U.S. Forest Service permission to gun down “approximately” 150 head of cattle in a remote, back-country area of New Mexico known as the Gila Wilderness. The motive was ecological: These cattle have demonstrably harmed Gila’s water supply, flora and fauna, and overall environment.

Both ranchers and animal activists are concerned about what they consider to be government overreach in the management of domestic and wild animals on public land. Beyond that, these uneasy bedfellows can’t agree on what the root problem is — or the best way to fix it.

Why Ranchers Object

Ranchers have been fighting the kill order from the get-go.

“Ever since they started shooting cattle two years ago, we’ve been fighting back,” said Loren Patterson, president of the New Mexico Cattle Growers Association. “We have tried to stop them with temporary restraining orders, and last year the government offered a settlement and opportunity to agree. We’ve been going back and forth for a year, and explaining the many other options of dealing with it.”

The preferred solution that Patterson and other ranchers presented involved the association, along with nearby ranchers, going into Gila to round up the cattle, ensuring they didn’t belong to anyone, then purchasing them from the New Mexico livestock board at a discount. The ranchers would ultimately be able to sell them for a profit.

But Patterson said that the Forest Service opted to leave the negotiating table and grab their guns. He argues that the agency never did its due diligence, leaving the root of the problem festering for decades.

“The whole issue got started about 50 years ago,” Patterson explained. “Over the decades, ranchers with grazing allotments have left or have been removed from the area, and while most of their herds were removed, a handful were left.” Over the decades, that handful “did what they do well, and that’s reproduce,” Patterson continued. While the government has gathered up hundreds of cattle over the years, there’s always a core handful that remain and reproduce.

“Plus, there are plenty of branded cattle that get in there too, because the Forest Service doesn’t properly maintain fences or corrals,” Patterson said. “So even if this inhumane slaughter eliminated all of the cattle there now — which I don’t believe it did, seeing as they only got 19 out of the alleged 150 they said were there — the same problem will crop up again soon enough because cattle will get in there without proper infrastructure and protection.”

Why Animal Advocates Object

Animal advocates are less focused on this one incident than the broader context of animal rights in the U.S.

“The slaughter was stark and troubling to be sure,” said Delcianna Winders, director of the Animal Law and Policy Institute at Vermont Law School. “But in the grand scheme of things, it’s a relatively small number of animals, and I think it’s important to look at the broader context of animal rights that this case raises.”

Winders said she thinks it’s “interesting” to see the cattle industry so quick to defend animal rights in the case.

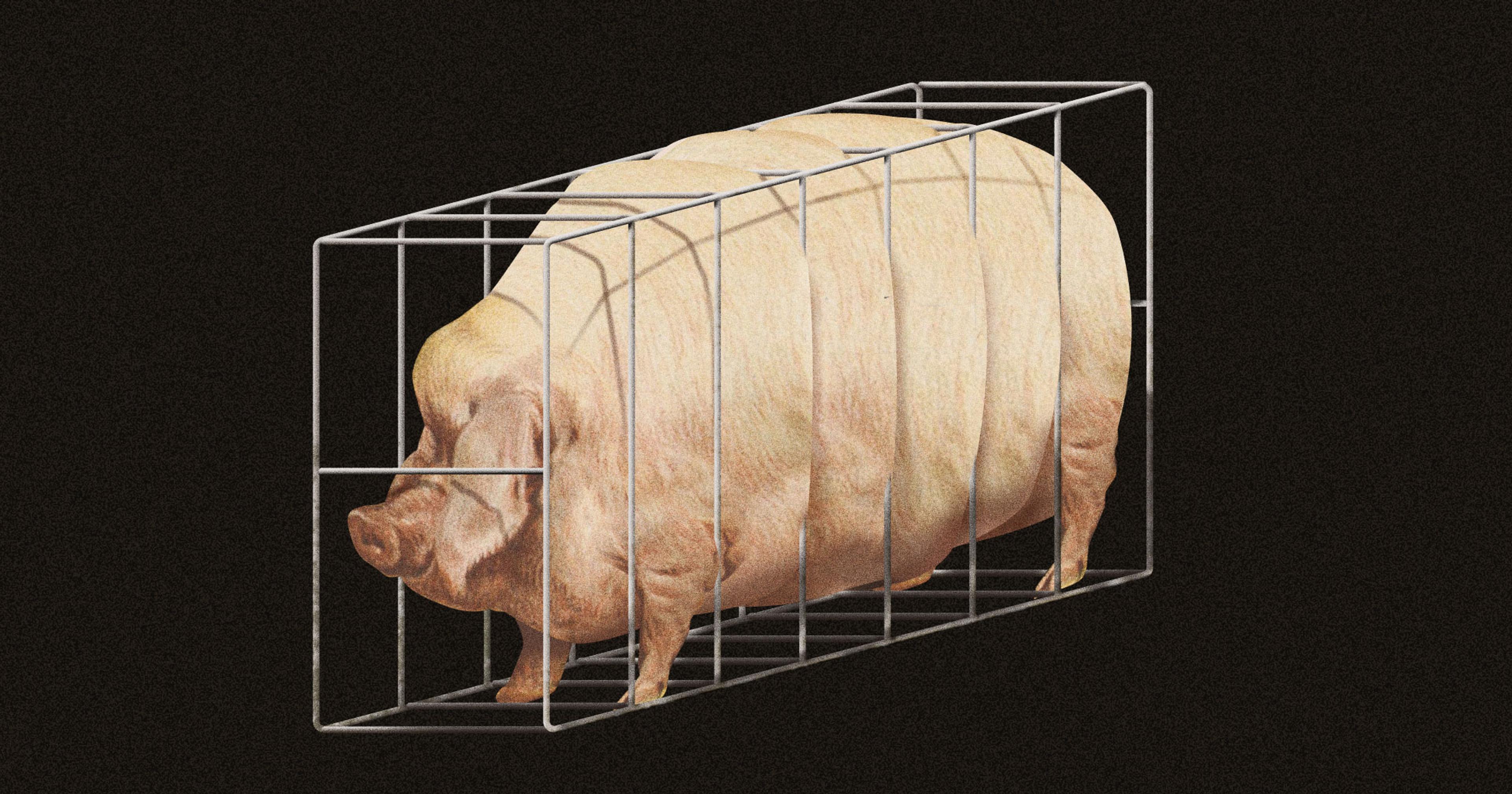

“This is an industry raising millions of cattle every year unprotected by federal laws,” Winders said. “They are routinely subjected to dehorning and castration without pain medication, they are weaned too early, and many remain conscious for several minutes after they’ve been strung up and had their throats cut.”

Winders said she and other animal rights advocates are concerned that the dramatic story of cattle being gunned down obscures larger issues. In addition to the day-to-day treatment of cattle, Winders said the government’s overly permissive approach to allowing ranchers to graze cattle and sheep on federal land needs to be addressed.

The Bureau of Land Management grants 155 million acres of grazing land to ranchers; close to 18,000 permits and leases are held by ranchers who graze their livestock on more than 21,000 allotments.

“The cattle industry is essentially being propped up by the American taxpayer in terms of land grants and subsidized feed from the soy and grain industry,” Winders argued. “Ignoring the day-to-day suffering of these cattle while bringing up the inhumanity of gunning down animals is hypocritical. At every turn, these ranchers get funding from the government, but despite their claims of concern over animal rights, what these ranchers are really motivated by is money.”

Inaction Not an Option

According to the Forest Service, the decision to remove the feral cattle using lethal methods was the only viable solution to what the agency describes as a threat to public safety and endangered species habitats. While interview requests with the Forest Service went unanswered, representatives did issue public statements repeatedly to that effect. Gila National Forest Supervisor Camille Howes argued that it was, in fact, the only viable solution.

“This has been a difficult decision, but the lethal removal of feral cattle from the Gila Wilderness is necessary to protect public safety, threatened and endangered species habitats, water quality, and the natural character of the Gila Wilderness,” said Howes. “The feral cattle in the Gila Wilderness have been aggressive towards wilderness visitors, graze year-round, and trample stream banks and springs, causing erosion and sedimentation. This action will help restore the wilderness character of the Gila Wilderness enjoyed by visitors from across the country.”

If the cattle were left alone, they would continue to breed, and the potential for a visitor fatality or permanent damage to sensitive ecosystems would increase, federal officials and environmentalists argue.

In a statement, Todd Schulke, co-founder of the center for Biological Diversity applauded the “hard decision to use the most effective tools for removing feral cattle from the Gila Wilderness. We can expect immediate results — clean water, a healthy river, and restored wildlife habitat.”

No Easy Answers

Jennifer Best, Wildlife Law Program Director at Friends of Animals, is quick to say that while her organization is not involved in the case, she sees it as a symptom of a much larger, pervasive problem.

“We began to see a shift around 2017 in the way the federal government was approaching the treatment of animals,” Best said. “Both domesticated and wild … We have worked on several cases regarding the removal of wild horses from public land in favor of grazing cattle or sheep.”

And while Best said the government “should not be using cruel and unusual methods to shoot down animals on public land,” it should also “not be subsidizing the cattle and sheep on public lands.” While there are no easy solutions, Best said with an increased spotlight on the issue, she’s hopeful that advocacy groups and members of the public will take the government and other parties to task, ultimately “calling for more accountability.”

The spotlight has indeed been more intense of late. In addition to dozens of articles on the subject, and a flurry of press releases issued by environmental, ranching, and advocacy groups, even New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham (D) spoke out on the subject.

“I am disappointed in their lack of meaningful, long-term engagement with New Mexico stakeholders on controversial matters like this one,” Grisham said in a statement. “Whether debating prescribed burns or wildlife management, it is imperative that New Mexicans who live and work in and near impacted areas are allowed the time to be meaningfully involved in these decisions. When that does not occur, it fosters a continued climate of distrust and hinders progress toward our shared goals of a healthy environment and a thriving rural economy.”

In an ideal world, Patterson said area ranchers could have helped or advised the Forest Service on how to “round up the stray cattle. Branded cattle could have been returned to their owners, and the unbranded, as per New Mexico livestock code, could have gone to a livestock market and sold.”

“In another year or two, there will be a whole new population of feral cattle to contend with because the Forest Service isn’t getting to the root of the problem.”

But as Best alluded to, the government has been increasingly quick to use lethal measures to eliminate what it sees as problematic populations of animals — both wild and domestic.

In recent years, the Forest Service and the U.S. Department of Agriculture have been authorized to use so-called cyanide bombs to kill coyotes, foxes, and other animals considered to be threats to ranchers and farmers; wildlife officials have been granted permission to gun down wild hogs with AR-15s; and the Bureau of Land Management has been rounding up wild horses and burros, which spawned a trade in cross-national horse meat.

On the topic of meat, could those 19 slaughtered cows have been used for food? New Mexico has one of the highest rates of food insecurity in the nation, with 1 in 5 children there facing hunger, according to Feeding America.

“The meat from those cows could have been used to feed people,” Patterson said. “It would have taken some extra steps, and some extra time to ensure the meat got collected and processed with all of the state statutes in mind. But we could have found a solution if they hadn’t been in such a hurry.”

A hurry, Patterson continued, to put a thumb in a dike riddled with holes. “In another year or two, there will be a whole new population of feral cattle to contend with because the Forest Service isn’t getting to the root of the problem,” he said.

It’s a blanket statement many would likely agree with — even if, again, a definition of the problem and its potential solutions would be up for debate.