More than a dozen breeding programs across the country are competing to develop the next great chipping potato. The impact will be felt far beyond the snack aisle.

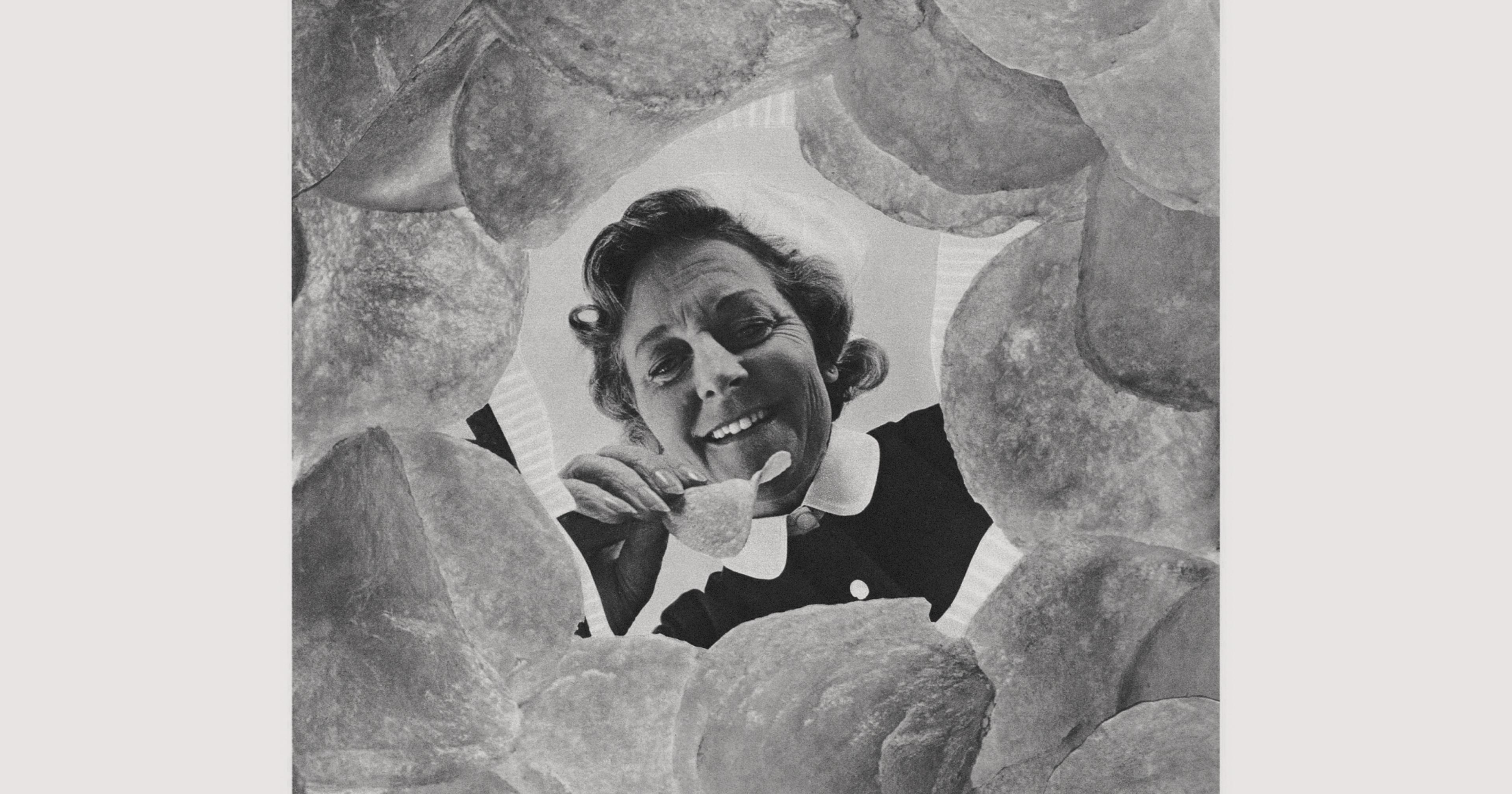

What makes a good potato chip? For starters, it should be crispy and satisfyingly crunchy, emerging from the bag fully intact without any shards. It should be perfectly golden, without any green spots or burnt edges. It should taste good, too.

For a chip with these qualities, not just any potato will do. Spuds destined for chips, referred to as “chippers” in the industry, require different traits than the russets on your dinner table. “Chippers have to be a certain size and shape to fit through processing machines so they can be sliced appropriately and form the right sized potato chip,” said Jessica Chitwood-Brown, assistant professor of potato breeding and genetics at Colorado State University, who also consider qualities like shape, coloring, sugars, yield, and disease resistance when cultivating new varieties. These details could make or break a potato’s popularity among processors — and, more importantly, consumers.

One of a dozen growers, processors, and researchers participating in the National Chip Program (NCP), Chitwood-Brown is competing in a race to breed the next great chipper potato.

With an annual budget of nearly $1 million, the coast-to-coast initiative is part collaboration, part competition, and is funded by Potatoes USA, a national organization whose mission is to promote potatoes.

It might seem like investing so much money specifically into breeding potatoes for chips is small potatoes. However, the U.S. is the world’s leading chip producer, with about 60 million cwt (6.7 billion pounds) of the annual crop supporting the country’s potato chip industry, valued at more than $22 billion. “We’re talking about potato chips, which you don’t think about as a major food source for the world,” said Chitwood-Brown. “But potatoes really are a staple crop.” And the lessons she and her competition learn from breeding chipping potatoes could be applicable to modernizing and/or improving production of other potato categories.

Potatoes are the most grown vegetable in the United States, followed by tomatoes, sweet corn, and lettuce. They’re also growing increasingly threatened by rising temperatures, which can lead to a drastic reduction in yield. In 2022, the U.S. grew an estimated 397 million cwt (44 billion pounds) of potatoes, the first time since 1866 that the annual potato production declined for five consecutive years. Last year, Idaho — which grows more potatoes than any other state — saw its lowest yield since 2001. In recent years, heat and drought in the West have hindered potato production so much that Maine sent millions of pounds of the crop to Washington processors in need of supply.

“The stuff that’s generated here in Idaho, it might not do well where it’s a lot more humid or hot, like in Florida.”

The NCP researchers’ shared goal is to ensure a year-round chipper supply that is strong and resilient, not easily disrupted by climate-related issues such as drought and floods. They share research findings, trial fields, and materials, and collectively wish to see more fields planted with potatoes resistant to diseases such as late blight, which caused the Irish potato famine in the 1840s.

The collaborative nature of the program is key to pushing breeding trials along. Each participant evaluates potato varieties based on 20 different factors, including yield, storage qualities, and fry color (nobody likes a dark brown potato chip). What thrives in one region might not grow well in another.

“We can come together, put the varieties into these trials, and see how well they do in different areas,” said Rhett Spear, assistant professor and potato variety development specialist with the University of Idaho Extension. “The stuff that’s generated here in Idaho, it might not do well where it’s a lot more humid or a lot more hot, like in Florida, and stuff that grows down there might not do as well where it gets colder, since it has less of a growing season here. So it’s good to see, you know, how they do in different areas.”

In Colorado, where farmers have in recent years been punished by drought and water restrictions, Chitwood-Brown is especially focused on breeding for drought resilience. As we’ve seen with the USDA’s $15 million Klamath agricultural project — which aims to restore and manage the Klamath River that flows through Oregon and northern California, an important breeding route for salmon and suckerfish — water is a precious and increasingly limited resource. Further, as Grist recently reported, federal authorities seem more concerned with supporting the thousands of acres of potato farms in the basin, which sell to major companies like Frito Lay and In-N-Out Burger, than rebuilding and sustaining wild fish populations.

“They’re America’s favorite vegetable, and outsell every other vegetable by a landslide.”

“Water is becoming more and more of an issue in all potato-growing regions, but especially in the West. And potatoes need water — potatoes are made of water — but there are ways to grow and varieties to use that require less water,” she said. “Having plants that are more tolerant and capable of maintaining themselves and being grown with less input is incredibly important for the sustainability of agriculture everywhere, but especially in our country.”

The fruits (or tubers?) of their labor might not be seen right away. “We have anywhere from 12 to 15 years, from the time that the varieties are crossed to the time that we’re able to release them and name them and the industry can get a hold of them,” said Spear.

Since being formed in 2008, the NCP trial has generated four new chipping varieties — Lady Liberty, Manistee, Hodag, and Mackinaw — that are now being grown on 7,785 seed acres, according to John Lundeen, research director for Potatoes USA.

When it comes to potato chip innovation, market needs are generally the force driving a breeder’s efforts forward. But for plant breeders like Chitwood-Brown, the work holds a deeper meaning. “They’re America’s favorite vegetable, and outsell every other vegetable by a landslide,” she said. “The potato growers here in my state are also my friends. This is their business, this is their livelihood. If their farm collapses because they don’t have potatoes that can be grown in certain conditions … I’m thinking about those things, too. The plants and the research that I’m doing actually helps to support a whole economic system. People’s lives and livelihoods depend on that.”