An Ambrook tech worker leaves Brooklyn for hands-on training in hog slaughter and butchery — as it was practiced in the 16th century.

Warning: The imagery in this piece is graphic as it fully depicts the process of harvesting and butchering a pig.

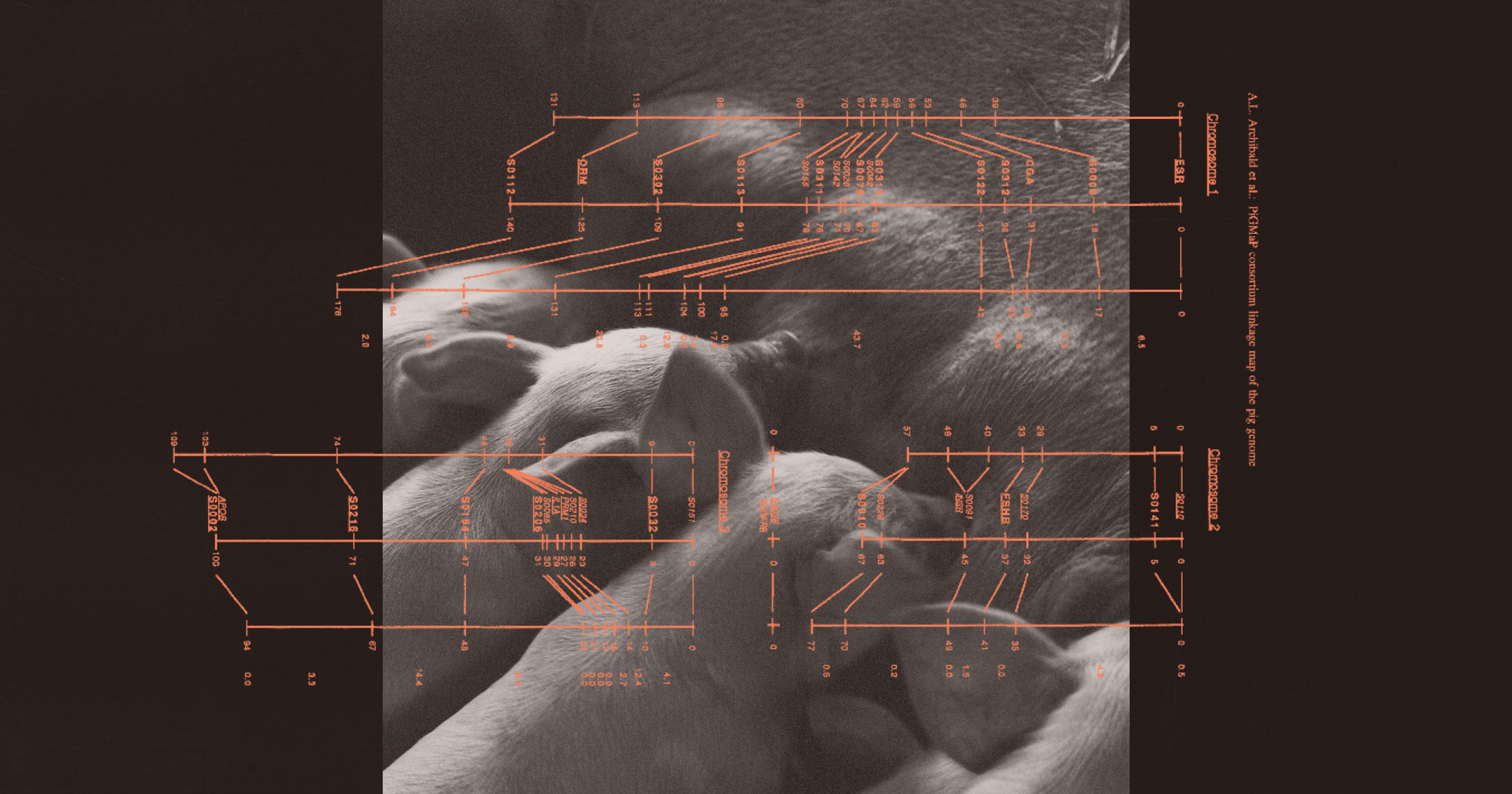

Brandon Sheard refers to himself simply as a “mobile slaughterman,” but I think that’s a bit modest. He’s a literal renaissance man — Brandon has a graduate degree in English Renaissance Literature and can reference works from Thomas Aquinas and George Orwell alike. Meanwhile, through his business Farmstead Meatsmith, Brandon roams the country teaching folks about animal harvesting as it was practiced in the 16th century. He posts educational videos on YouTube, manages an online community for aspiring meatsmiths, gives presentations all over the country, and is working on a new book about charcuterie.

Brandon’s many layers weave together seamlessly in a colorful two-day show with the billing “traditional pig harvest,” some combination of sermon, science class, and stand-up routine. This was not a show I ever expected to witness.

I had been working here for about two weeks when I got a casual Slack message: “Do you want to go to a traditional pig harvest with a few other Ambrookers?” Like any eager new employee my response was, “Of course!” It wasn’t until the next morning that I thought to look up what a pig harvest actually is — it’s not like harvesting apples.

I was surprised, but not put off. Bacon is my go-to breakfast food and “hotdog” was my first email password — I couldn’t pass up this opportunity. And, like the old saying goes, “No better way to get to know your coworkers than butchering a hog together.”

Excluding my crew, everyone who attended the class was there to learn about the practical techniques — and the virtues — of pig harvesting, specifically from Brandon Sheard. To quote one attendee, “When I saw he was doing a class in the Northeast I booked it immediately. I figured he might not be back this way again.” Some guests were considering raising their first pigs and needed the full lesson, start to finish. Others had been raising and harvesting pigs for a while and wanted to refine their craft. One attendee didn’t own any pigs at all; he was simply enthralled with this iconic meatsmith.

Brandon Sheard

A traditional pig harvest starts with Brandon’s mandate to “maintain tranquility.” Tranquility is a hard thing to define, especially from the perspective of the pig, but the idea is to minimize the amount of stress an animal feels before dying. The process centers on “discerning the nature” of the pigs. For example, when doing a harvest Brandon chooses to do the slaughtering in front of the herd because “pigs don’t fear death, they fear being alone.” He identifies the alpha (“Boss Pig”) in the sounder to make sure it is slaughtered last. That’s the pig who’s least likely to freak out in solitude and attempt an escape.

Tranquility is both the means and the end when you’re actually performing a kill. If you have to slaughter an animal, a bullet to the brain is the best way to minimize pain. That said, a pig’s brain is roughly the size of a tennis ball — if you miss, chaos ensues. So patience is key. Put another way: “The only thing harder than shooting a pig once, is only shooting a pig twice.”

As Brandon circled the pen and stalked his target it was so quiet you could hear a pig pee (we did). It’s one of the few times that a pig sits still. Brandon would lean in for the shot, something would shift, and he’d start circling again. Watching this dance for seven long minutes felt like an hour but, after a split second and a deafening bang, it was over.

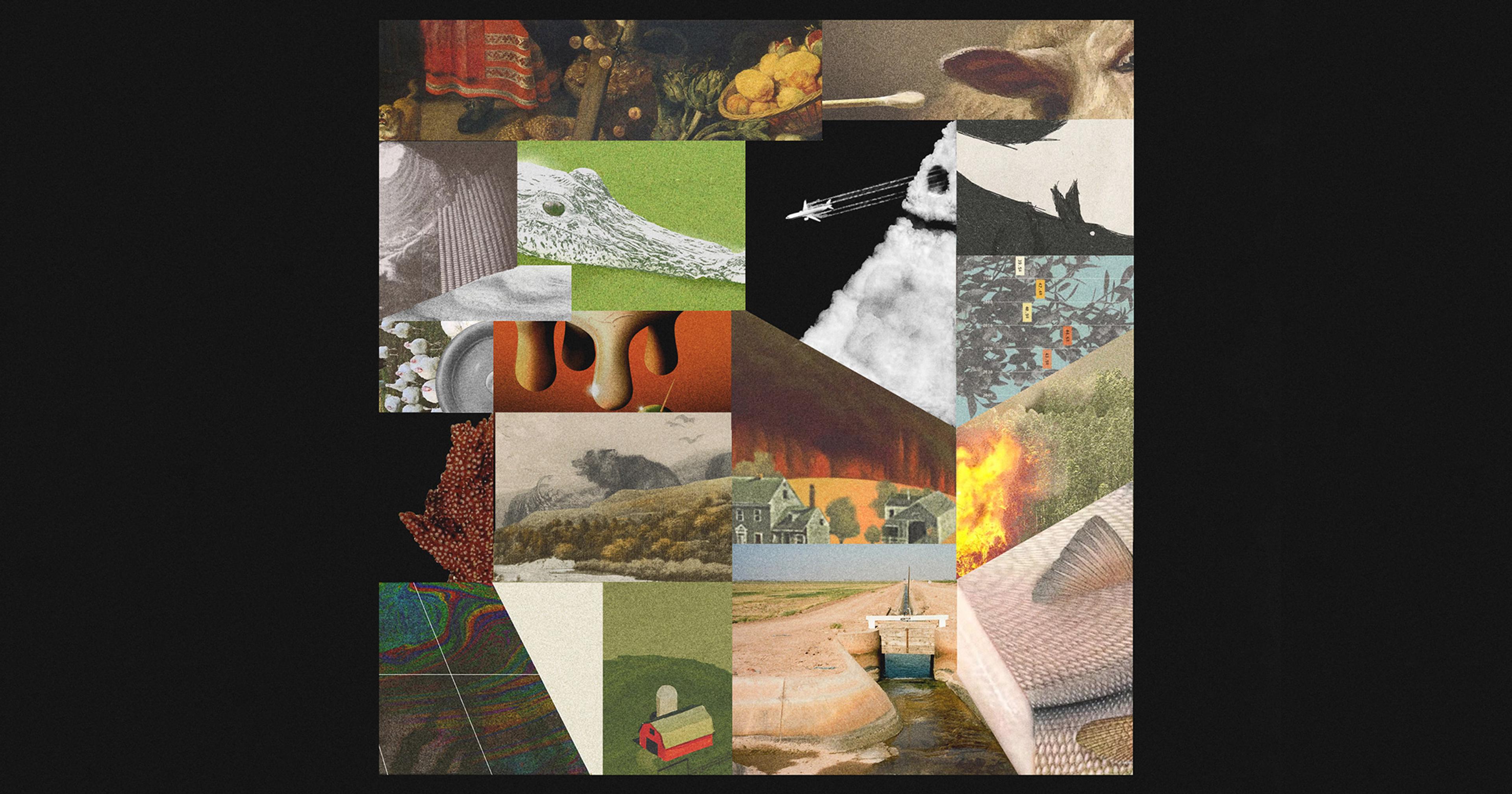

After the slaughter, my classmates and I were put to work scalding the pig and removing its hair, learning technique and breaking a sweat along the way. My Ambrook colleagues removed toenails and sawed bones in half (team bonding?). A small older woman bearhugged the head and yanked it right off. Then we got to what Brandon affectionately referred to as “gut town.” I thrust my bare hands into the town and came out with a trachea and lungs. Brandon taught us that you can fully reinflate the lungs by blowing through the aorta — not a party trick for all audiences.

While all this was happening, Brandon continually invoked food to remind us of the purpose behind the pig slaughter. Blood becomes boudin noir, the head becomes torchon, small intestines become sausage casing, liver becomes pâté, eating the pizzle is optional. We loaded our handiwork onto the bed of a pickup truck and covered it up with garbage bags to avoid shocking the farm’s CSA customers. Lots of people want farm-to-table food, but if you haven’t seen the process up close it’s easy to forget that there are gruesome, possibly traumatic steps in between.

The second day of class focused on butchery and charcuterie; we learned that both skills are more art than science. According to Brandon, people who come to the class without prior knife-wielding experience can sometimes experience “cut anxiety” — the fear of making a wrong slice and ruining the integrity of the meat. Alleviating this anxiety is just a matter of perspective. So long as the end product is a piece of meat that can be braised, boiled, or roasted, you’ve achieved success. And, if worst comes to wurst, spare cuts can be ground up for sausage mix, because “sausage … is forgiveness.”

The philosophy for curing is similar, with the rule of thumb being, there are no rules. Recipes are to be generally disregarded. You mix your salts and spices in a ratio, apply roughly 2 percent of the mix by weight, and let the cosmos take care of the rest. (Brandon frequently references the cosmos in his running sermons.) In Spain, they have folks whose job it is to know when a jamón is done based on the smell. There’s no recipe, just God-given instinct. A cure can take anywhere from two to five years depending on the meat — and the inclination of the nose in charge.

In the weeks following the harvest, I had the feeling I had seen something profound. Still, I was having a hard time putting words to the experience, so I went to Brandon’s YouTube channel. As he puts it, the virtue of pig killing is that “it gives you a context that actually is in harmony with the natural order.” For Brandon, the natural order refers to God’s natural order. The “traditions” of pig harvesting are organized around days on the liturgical calendar because that is when people had time off from work. The notion of harvesting your pig in November and eating bacon all winter — when you can’t grow plants outside — is a submission to seasonality as God created it.

I’m not religious. When I was younger I was politely excused from Sunday School for asking the question “why?” too often. What I loved about Brandon was that “why” was never an issue, it was actually the point. Partaking in a pig harvest brought up all kinds of thematic questions for me: the spiritual (Is it okay to kill a pig?), the political (Why has our food system turned away from these methods?), and the practical (What do I do with all this extra fat?). Brandon has given all these questions serious thought and is refreshingly open to engaging. I can’t say I agree with him on every subject, but I can appreciate his thoughtfulness — his devoted following appreciates it too.

At our last, pork-heavy supper, I asked Brandon if he was going to take any detours on his drive back home to Oklahoma. He replied, “I’ll probably drop by a couple great churches in the mornings.” I would be looking for bars or barbeque. In many ways we couldn’t be more different, but ultimately we share some core values: craftsmanship, care, community, sustainability. We may have very different ways of living up to those values, but isn’t that the whole point of living?

After the event, I lugged 50 pounds of pork and 10 pounds of lard onto the Northeast Regional Amtrak, to bring friends and family sustenance for the impending New York winter. I felt different than I had before — and I’m grateful for that.