A distrust of urban living and government control, combined with the advent of remote work, has led to a different kind of “back to the land” movement in the U.S.

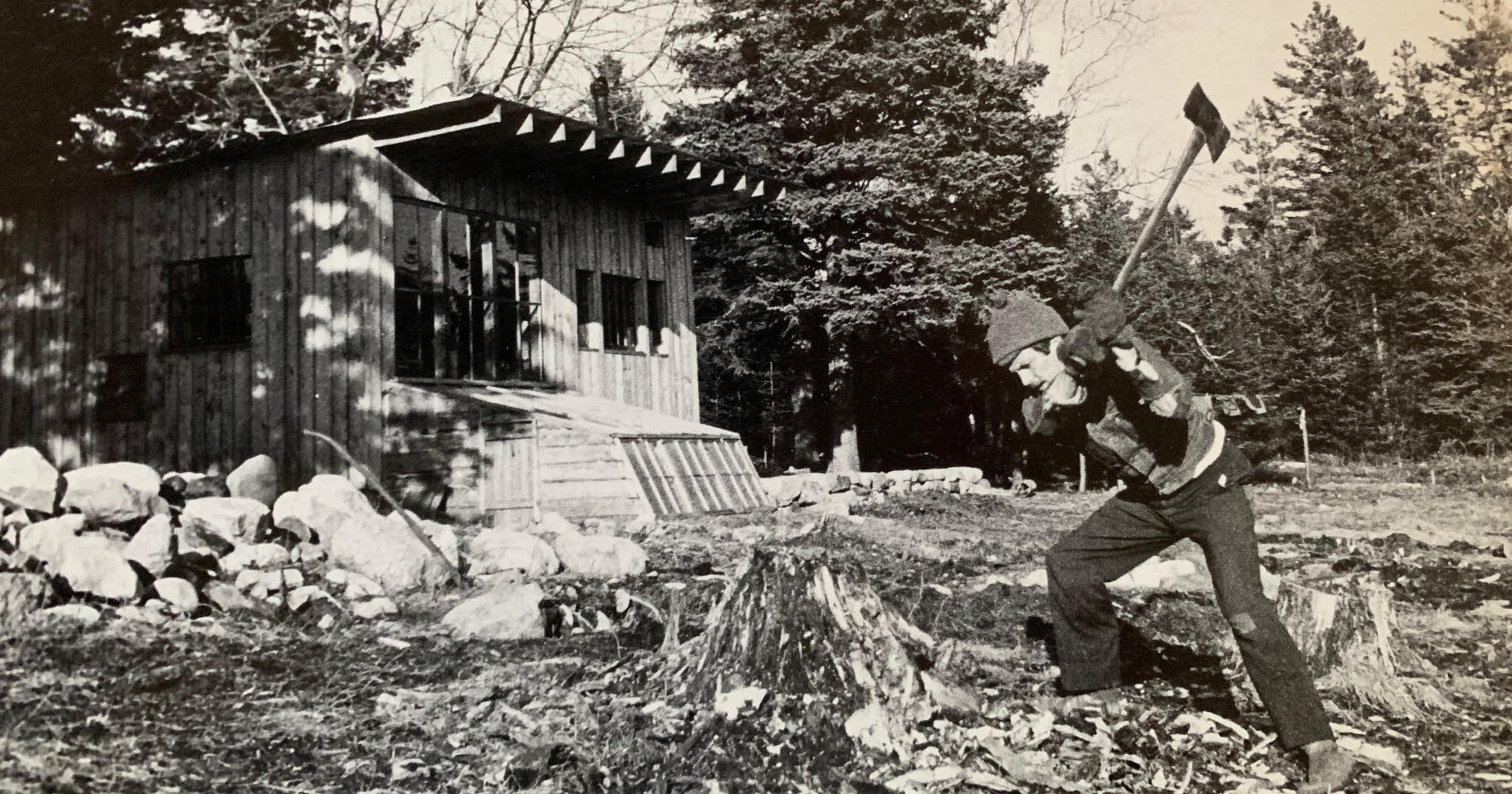

Much of the history of American homesteading movements is punctuated by visions of shared abundance and a spirit of collectivism. While they often don’t fit neatly into one belief system, many quests for off-grid agrarian living have leaned left, politically.

And yet, it would be an oversimplification to view the tendency towards agrarianism as inherently progressive. Interspersed throughout the hippie communes and ecosocialist experiments dotting the American countryside, religious separatists, libertarians, and other conservatives have been putting down roots for some time.

Whatever the ideological particularities — distrust of corporate power on the left, wariness of state intrusion on the right — rural living can be an enticing prospect for those tired of industrial society.

When the Covid-19 pandemic drove people indoors, many into confined city apartments, it inflamed anti-urban sentiments that were already latent with the ideological right. The ensuing proliferation of remote work meant that those feeling city claustrophobia could now more realistically exit for the country.

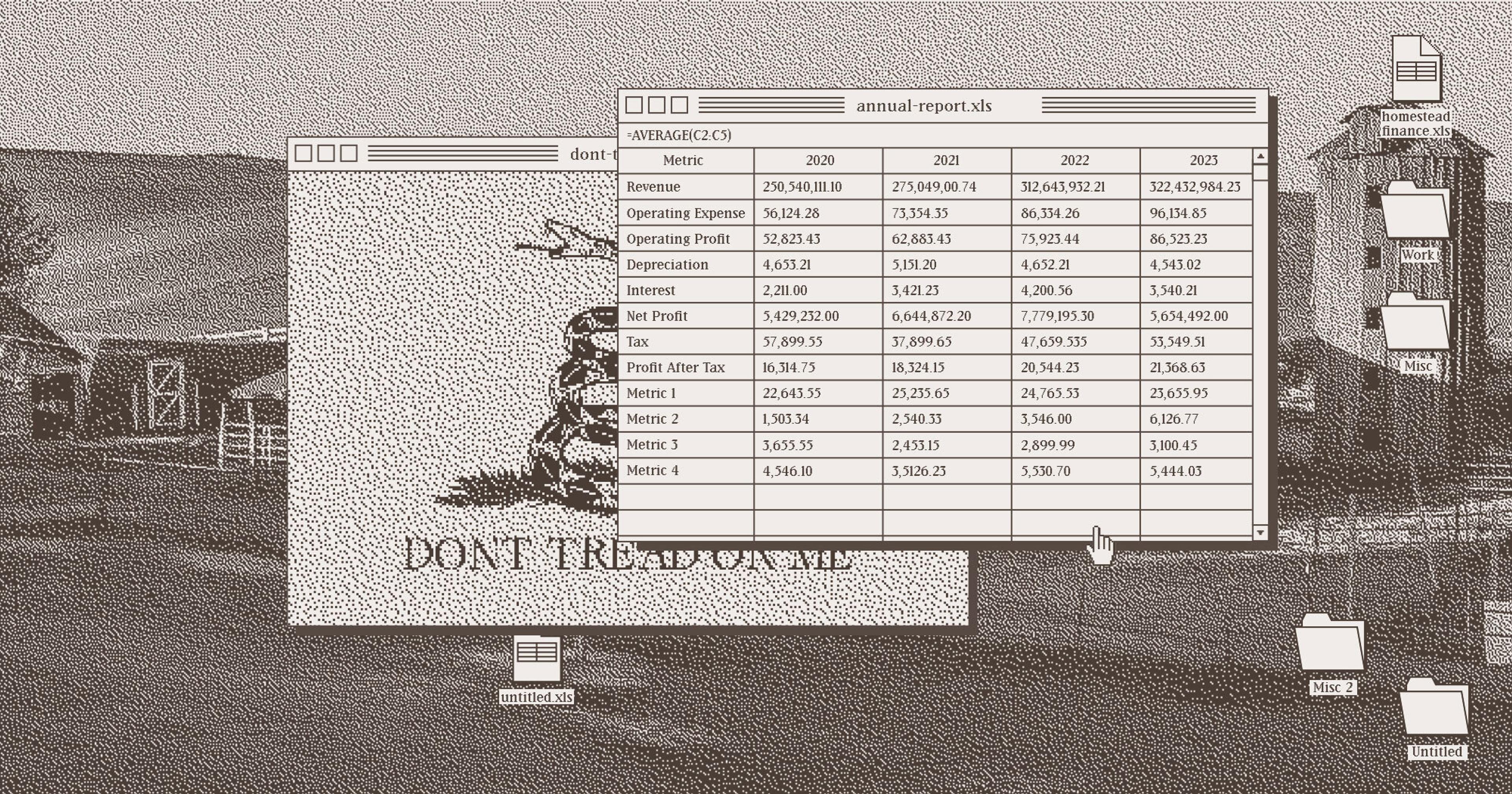

RidgeRunner, a real estate firm based in Kentucky, is offering opportunities in Appalachia, marketed squarely to aspiring conservative homesteaders. Their latest undertaking is the “Highland Rim Project,” a land development centered around a rural Tennessee town — they plan to disclose the specific location in late 2024/early 2025, working until then to acquire properties and gin up demand. Many of these plots will be marketed to those who want to, at least in some capacity, “live off the land.”

RidgeRunner was created in partnership with the conservative venture capital firm New Founding. Nate Fischer and Joshua Abbotoy, both managing partners at NF, have deep connections to the Claremont Institute, an important think tank for the intellectual wing of the Trump movement. Its president, Ryan Williams, told The New York Times last year that, “We wanted to speak to a younger audience, to try to understand and influence the New Right in its varied factions and cultivate that audience for the better.”

The Highland Rim Project is the first, or at least most visible, example of the “New Right” carving out a community of their own on the homesteading frontier. Documented a year ago by James Pogue in Vanity Fair, this recent formation of the conservative movement takes pride in holding unorthodox views, favors a confrontational rhetorical style, and is composed mainly of disaffected professional class knowledge workers. They are a young and hyper-online cohort.

Like many reactionaries throughout history, they view America’s cities — where many of them live — as becoming hostile and unlivable. Their pessimistic view of the modern city identifies liberalism writ large as responsible for homelessness, crime, and drug addiction.

“The holler is your own little fortress, where you have a water source, space to grow crops, run livestock and shoot deer.”

Abbotoy, who is also a partner at RidgeRunner (which he runs with his father), painted a bleak picture of American cities during a recent podcast with his business partner, Santiago Pliego. Reflecting on those early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, Abbotoy recalled:

“I think part of it was with the lockdowns … you’re under this kind of oppressive condition where, if you leave the front door of your house, you’re subject to all of these rules, and the public eye is on you. And, if you have your own land, you do what you want.”

When federal, state, and local governments responded to Covid-19 with restrictive measures on economic and civic life, many on the right saw this as the perfect expression of an overly-centralized state.

While conservatives like Abbotoy bristled at the lockdowns, these policies are what spurred on the meteoric spread of remote work. Ironically, this ultimately created the conditions of professional class hypermobility required for the Highland Rim Project.

Dona Brown, a historian of back-to-the-land movements at University of Vermont, has found that homesteaders throughout history and across the political spectrum share one common outlook: “I think there’s always been a powerful tendency for back-to-the-landers to be in one way or another decentralists, to try to pull back the power and the technology and the skills to the individual or the collective homestead level.”

“You’re under this kind of oppressive condition where, if you leave the front door of your house, you’re subject to all of these rules, and the public eye is on you.“

For the men involved in the Highland Rim Project, this relocation of power away from the state is helped by the physical geography of the Appalachian region. The post at the top of RidgeRunner’s Twitter account (or “X”, as it has been rebranded by Elon Musk — a favorite ideologue of the New Right) reads:

“Sometimes people ask us what a “holler” is.

It is a magical little Appalachian valley.

Ideally, you own all of it - ridgetop to ridgetop and the holler is your own little fortress, where you have a water source, space to grow crops, run livestock and shoot deer.”

Above the text is drone footage of bucolic farmland, hugged by wooded hills and a trickling creek. The property, ostensibly one of RidgeRunner’s, is undeniably beautiful. As promised in the tweet, this land looks and feels private — tucked into tree-dense ridges, a person (and their family) could indeed build their “own little fortress.”

They query their prospective customers:

“Why not buy a holler farm from RidgeRunner? Given their natural beauty and diverse range of potential uses, it’s an incredible value. Work from home, hunt, farmstead, and let your kids run free on your own hundred acre domain.”

The New Founding website spells out very clearly the main demographic that they are courting: “Remote work enables a revolution in where people live and how they organize themselves into communities. People are, especially since Covid, proactively seeking communities that align with their values and way of life.”

In most ways, the demographic slice that the Highland Rim Project is speaking to — the right-wing remote worker — is a new class, particular to this moment in history. Interestingly, when I asked Brown what most homesteaders had done for work in the past, she laughed and said, “The job they most often used to support their back to the land enterprises was writing books about going back to the land.”

In the not-very-distant past, a move to the country almost always meant a compromise to one’s income. RidgeRunner and New Founding are curating opportunities for people tired of the city’s concrete, the social challenges, its liberal culture — but who want to (and now, can) bring their jobs with them into the homestead.

“When I have choices about businesses to try to lure in, I want the business that says I want to do high-end Appalachian charcuterie.“

With the Highland Rim Project, a grass-fed beef farmer — a profession revered by Abbotoy and his peers — could now support an ordinarily hard-scrabble livelihood with a tech-worker’s earnings.

Abbotoy is clear-eyed in his assessment of who exactly his primary buyer will be. Apart from political persuasion, they are, as he told me, “likely to have higher incomes than the people who are on the ground right now,” and sees the importance in appealing to their “coastal tastes.”

He recognizes that the native culture of the areas that RidgeRunner is developing might not offer enough for the transplant coming from New York City or Silicon Valley. “When I have choices about businesses to try to lure in, I want the business that says I want to do high-end Appalachian charcuterie, like country ham. And people who want to do products or services that are kind of prepared in traditional ways, are resonant with the local culture, but also, at times we’ll have an opportunity to elevate that.”

At the cultural level, the online right has identified numerous features they see in urban life that offend their tastes. The politics of the Black Lives Matter movement, a progressive view of immigration, and the growing support for trans rights, are some of the developments popular in the city that animate their reaction. (The New Right follows a long tradition of conservatives ignoring the actual diversity found in rural communities.)

In the podcast with Pliego, Abbotoy voiced a concern heard commonly in his quarters: “If you’re in California, the state can take your kid and trans them without your consent. For me, I don’t really think somebody with kids should live there.”

Abbotoy is likely referencing California legislation, introduced in September 2023, which would have directed courts in the state to consider a parent’s attitude towards affirming their child’s gender identity (amongst many other factors) when deciding custody. That bill was vetoed by Governor Newsom later that same month, well before the podcast with Abbotoy and Pliego dropped in January 2024.

The New Right-wingers might be new in their updated brand of conservative populism. But in at least one key way their attitude is much like their forebears: Both real and imagined threats to traditional cultural norms can make them want to build up a fortress. It seems Tennessee has some pretty good hollers for that.