In the 1970s, one million Americans attempted an off-grid, self-sustaining homestead lifestyle. It wasn’t easy, but it was life on their own terms.

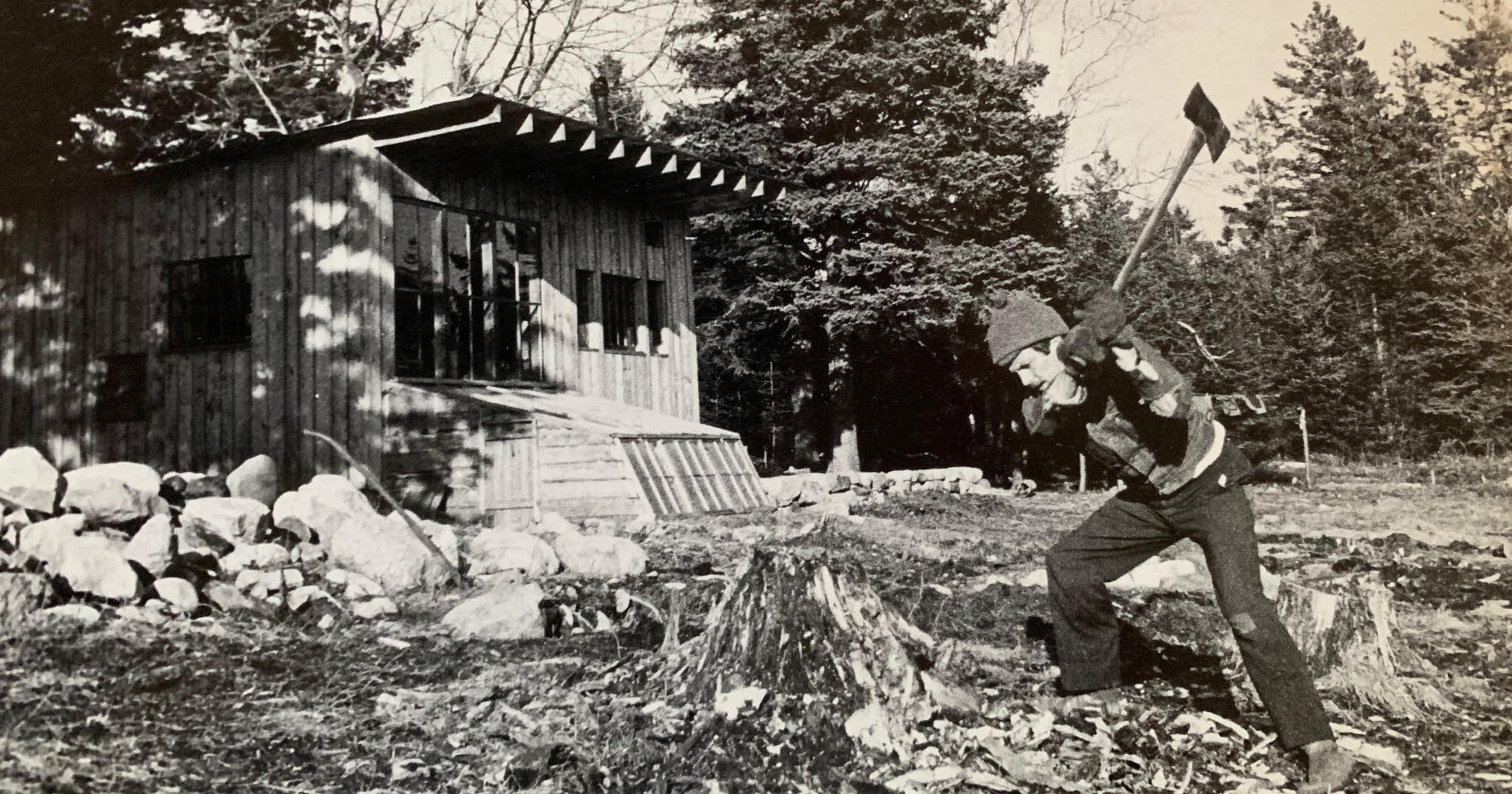

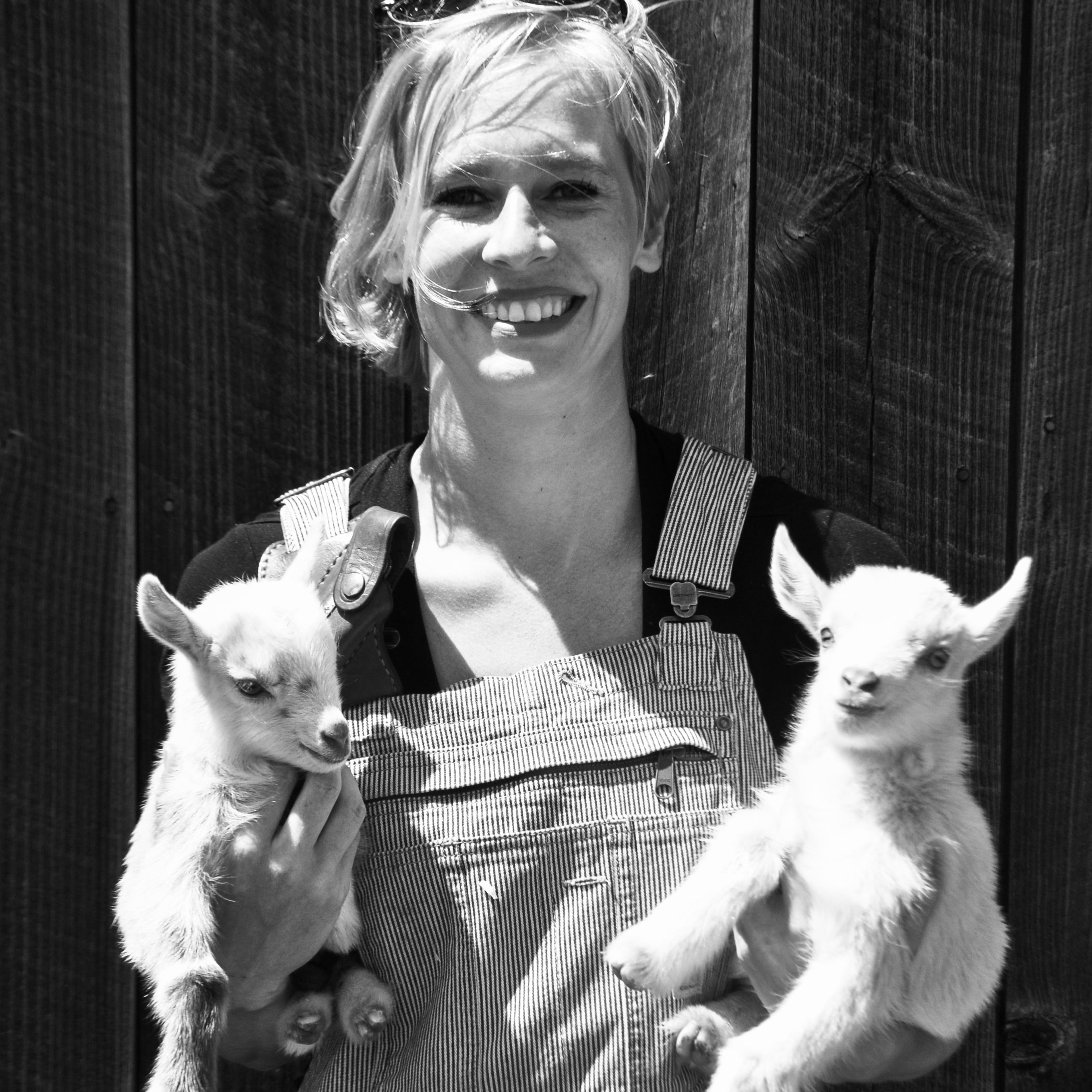

The year is 1975. An overloaded UHaul pulls into a clearing in the remote Maine woods. In one corner of the clearing, a bare-bones plywood shack crouches. Out of the truck clambers my mother, a skinny blonde in a bulky sweater with a sleeping baby girl clutched to her hip, and her first husband, a full beard and long hair spilling down his back. In the back of the UHaul are some dairy goats, bleating pensively, and every object that made up their young, newlywed lives.

My mother was part of the back-to-the-land movement of the 1960s and ‘70s, a generational exodus to the countryside that was so noticeable it changed census statistics. In sleepy Waldo County, Maine, where I now live, the population grew by more than 20 percent between 1970 and 1980. People around the country went rural — there were movements in the Ozarks and along the West Coast — but Maine and Vermont served as something of a Mecca for aspiring homesteaders.

Lie-Nielsen's mother poses with sunflowers in her garden in the 1970's.

Who Were the Homesteaders?

The modern self-sufficiency movement arguably started in the mid-1800s when Henry David Thoreau published Walden, his seminal reflection on two years of solitary self-reliance. In the 1930s and ‘40s, homesteading grew in popularity as part of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Subsistence Homestead program and the recovery from the Great Depression. And we’re currently in the midst of a self-sufficiency renaissance, where increasing numbers of urban Americans are attempting to make a go of it on their own. There are consistent themes to all of these movements but in the 1960s and ‘70s, going back-to-the-land was part of the broader counterculture movement, rejecting many of the trappings of mainstream society. In the 1970s alone, over one million people were inspired to move to the country.

“Everywhere you looked the counterculture movement was going on,” said my mother, “snd a lot of it had to do with going back to the land.”

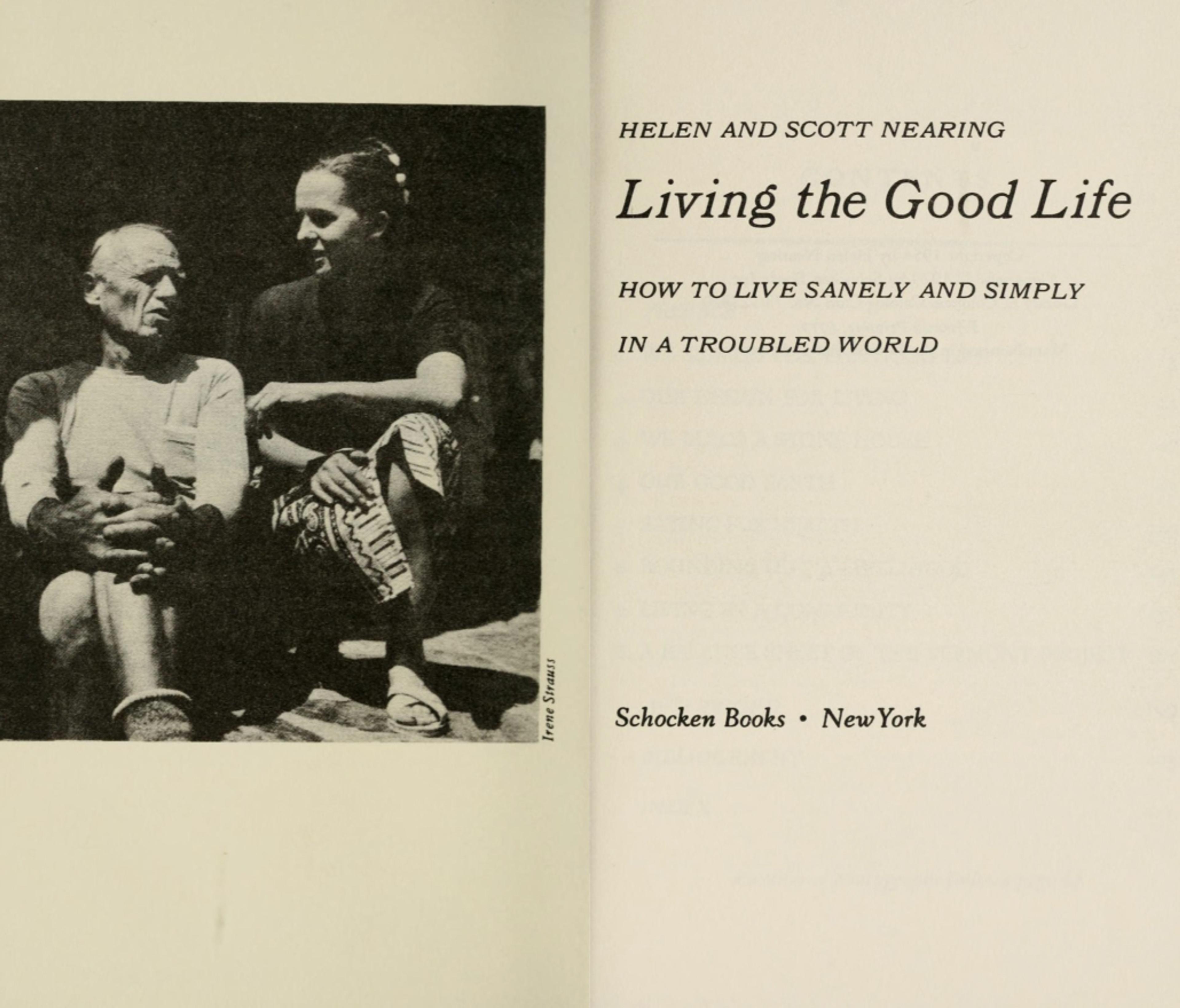

It’s no fluke that Vermont and Maine became homesteading destinations for so many — it’s all about one couple named Helen and Scott Nearing. The Nearings started homesteading in rural Vermont in 1932, decades before the so-called hippie movement took off. The seminal work of the homesteading movement, the Nearings’ Living the Good Life: How to Live Sanely and Simply in a Troubled World, was published in 1950.

In 1952 they moved to Brookside, Maine, where they established a homestead that would eventually become the Good Life Center. Yet it would be more than a decade before the homesteading movement really took off, fueled by disillusionment with modern society and politics and embracing the ideals of environmentalism and personal freedom at all costs. Living The Good Life was republished in 1970 by Schocken Books. The new edition of the book became a sensation, inspiring a generation of back-to-the-landers, many of whom arrived at the Nearings’ homestead hoping to learn from the masters of simple living.

Stewart Brand, writer and editor of the counterculture magazine The Whole Earth Catalog, captured this newly embraced understanding of our environmental impacts and personal sovereignty in saying, “We are as gods, and might as well get good at it.” The back-to-the-landers were dropping out of what they saw as a broken society, taking up life as stewards of the land and masters of their own needs.

Maine Beckons

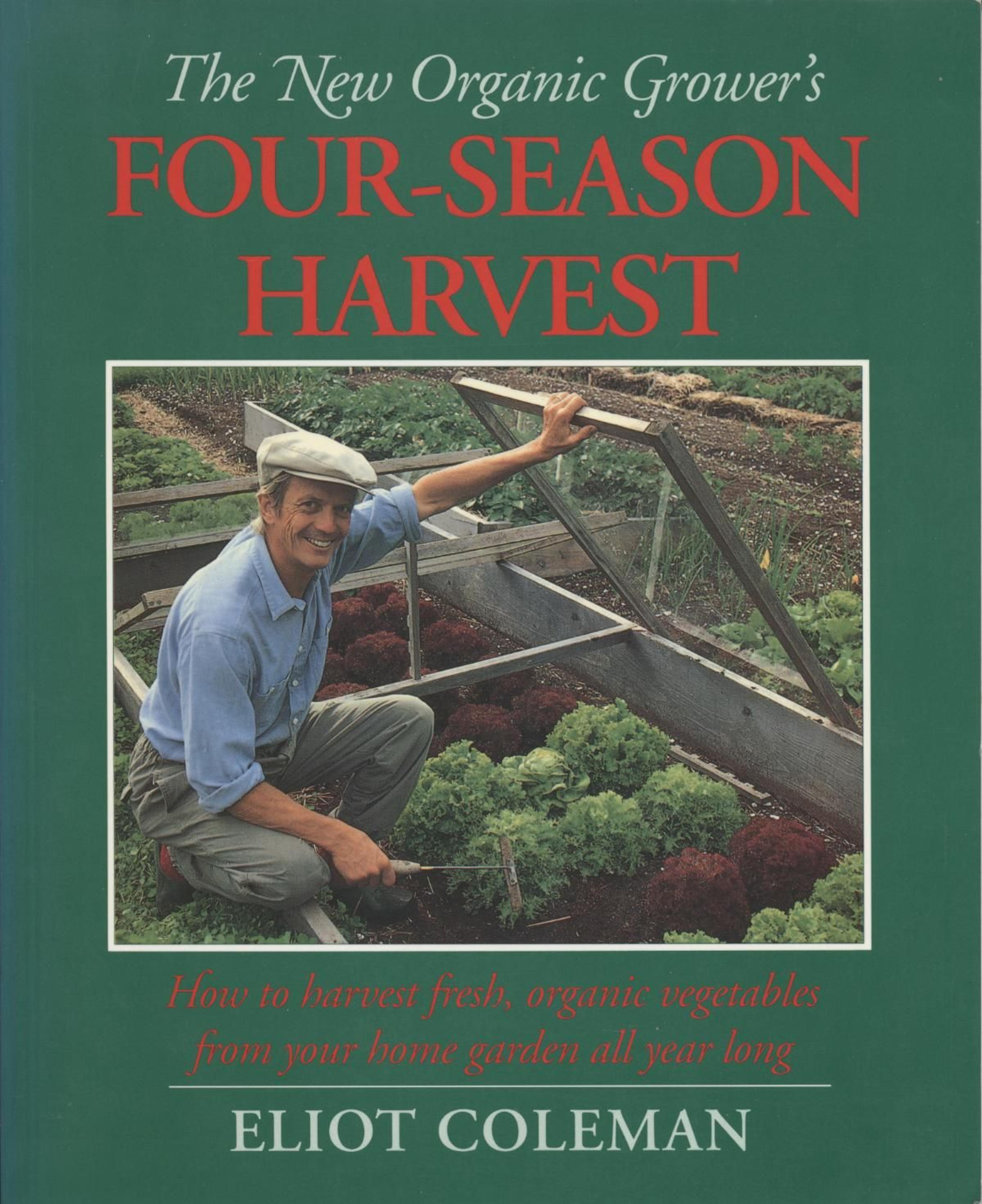

Eliot Coleman arrived in Maine in 1968, frustrated with the status quo and in search of adventure. “A lot of the things that we saw back then frustrated us,” he said, “Like the war, and the way people treated each other. It seemed almost insolvable: We were just small nobodies up against this massive disconnect. But all of a sudden in agriculture, in growing food organically, we were able to disprove the dominant paradigm.”

Coleman came to Maine with his first wife, Sue, and $5,000 in savings. They visited the Nearings, and after a year Scott Nearing sold them 60 acres of wooded land for $2,000, reflecting the price that Helen and Scott had paid for the land 20 years prior. Coleman — now a household name among modern small-scale growers — would perfect the art of organic gardening in Maine’s harsh, seasonal climate.

Kal Winer and Linda Tatelbaum came to the sleepy, forested village of Burkettville in 1977. They found a piece of land in a clearing choked with milkweed, where a house had stood a hundred years before. Their first summer they built a temporary house, moving into it on a cold October night in 1977 when the frost forced them out of the camper they had stayed in over the summer.

“We dragged our mattress from the trailer in the middle of the night,” Tatelbaum remembers, “just to sleep inside the house.”

They intended for their first attempt at home-building to be a temporary structure, but over the decades they added living space to the building, rather than starting over again. Both Tatelbaum and Winer worked part-time, and spent the rest of their time working on their homestead projects.

Meanwhile, further north in Addison, Maine, my mother Karyn and her first husband, John, still had plans to build their own home instead of making camp in the old hunting cabin. “After a few years,” my mother said, “it was like … we aren’t building this house. We didn’t have the money to buy the materials. I thought we were going to build a stone house like the Nearings, but we hadn’t collected the stones.”

This guy, who I married, he really had an idea about building a log house and growing food — he made it sound so fabulous that I just would go anywhere with him.

My mother and her husband had come to their clearing in the woods with a dream and no money or backup plan. While my mother’s husband worked odd jobs in town, she would occasionally work as an interpreter for the deaf and taught preschool for a few years at the local school. But living the good life proved a challenge for them.

“I was 19 [when we moved to Maine],” my mother said, “and this particular lifestyle was on the cover of Life magazine, feature stories in other magazines. Everywhere you looked the counterculture movement was going on and a lot of it had to do with going back to the land. And this guy, who I married, he really had an idea about building a log house and growing food — he made it sound so fabulous that I just would go anywhere with him.”

Off-Grid Frugality

Most of the back-to-the-landers, including my mother and her husband, Tatelbaum and Winer, and the Colemans, embraced an entirely off-grid lifestyle.

“I was living in an interesting little house,” Eliot Coleman recalls. “My first wife and I built it for a thousand dollars back in ‘68. It wasn’t big, but it was simple and warm. We heated with wood, we had a well that we dug that we got water from, we dug a root cellar where we stored food over the winter. We didn’t have electricity, we didn’t have a phone — talk about economics! Without those bills coming in, there was nothing that could stop us.”

Coleman thinks that the frugality and unconventional lifestyle of some back-to-the-landers was a big part of their success. Trying to make a go of homesteading with a mortgage and bills to pay made it difficult, but fully “dropping out” of modern society could mean a whole new way of thriving. For Coleman, the way around these challenges was to eschew modern conveniences entirely. He had no mortgage for the land he bought from the Nearings, no electricity bill, and no heat bills for his woodstove.

“There were years we earned money growing vegetables,” Coleman said, “but it would run out by the middle of March. And so how are we going to get through until June, when we have crops to sell again? We had wheat in the grain bin, we had a grinder, and we had all these vegetables in the root cellar. So we would just eat and work for the next two and a half months, until we opened the farmstand. There were no bills coming in that we needed to pay, so the fact we had absolutely no money was just a really interesting way of looking at it.”

The Nearings had preached frugality in Living The Good Life and set an example of an off-grid homestead. Scott Nearing was a radical political activist who had published numerous pamphlets on communism and social revolution. When he sold his woodlot to Eliot Coleman for $33 an acre, he was reflecting the price he had paid for the land 20 years prior.

We were very much committed to living by the tenets and principles laid out by the Nearings. Pay as you go, vegetarianism, and self-sufficiency. We lived by them, even when our lifestyle was different from theirs.

“They were honest socialists who believed in living their talk,” Coleman recalls of the Nearings. “And we wouldn’t be here today if it hadn’t been for the Nearings making land available to us. A piece of land allows you to do all sorts of things that you can’t do without it.”

While Tatelbaum and Winer were still working part-time and had some bills to cover, they grew everything that they needed to eat at their Burkettville homestead.

“Especially in the early years,” Winer said, “we didn’t buy vegetables in the supermarket, even if we wanted them. To buy a head of broccoli in the middle of winter would’ve been nice, but we didn’t. We were eating what we had — and by spring we were pretty tired of it!”

The back-to-the-landers largely did not seek to enter into commerce with their farm, beyond perhaps a modest roadside farmstand. Few had ambitions of a large commercial crop or becoming the next big thing in agriculture. They just wanted to provide enough food for themselves and their families, and live peacefully alongside nature.

“We were very much committed to living by the tenets and principles laid out by the Nearings,” said Warren Berkowitz, who arrived in Maine with his wife in the early 1970s. “Pay as you go, vegetarianism, and self-sufficiency. We lived by them, even when our lifestyle was different from theirs.”

Community Support Systems

Berkowitz and his wife were part of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, which was founded in 1971, and participated in early Common Ground Fairs, an annual gathering of homesteaders that began in 1977. Their move to Maine was inspired by reading Living The Good Life, and it began with a visit to the Nearings’ Brooksville homestead, where they connected with more back-to-the-landers.

“The great thing at that time was there were literally hundreds and hundreds of people our age doing the same thing up here,” Berkowitz remembers. “I didn’t have support from my family back in New York — they thought I was crazy. So sharing child rearing, sharing all our homesteading activities with friends really made a huge difference.”

Past artwork for the Common Ground Country Fair.

·Archive Images from Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners

“It was fun to compare notes,” Coleman said, remembering his homesteading neighbors. “It was like being on an unexplored planet, and we’d just gotten off the spaceship and we had a lot to learn.”

Some back-to-the-landers embraced the idea of community to the point of creating communes for like-minded people to share the fruits and labors of homesteading. Nearly 2000 communes existed across 34 states by 1970, according to a New York Times article at the time. By spreading the toils of self-sufficiency across a community, communes sought to make the back-to-the-land lifestyle more achievable. But they were often predicated on shared values systems, which could lead to their dissolution. Some communes have survived until today, but most were lost over the decades.

Parents Just Don’t Understand

Many homesteaders faced resistance or confusion from their parents, who had provided all the modern comforts they could to their children.

“My mother used to refer to it as ‘when you went crazy,’” Coleman said, recalling his mother’s skepticism at his back-to-the-land leap. His mother’s opinion only changed when he started publishing books. “Now she could say ‘my son the author,’ not ‘my son the deadbeat who lives in the country.”

Lie-Nielsen's mother working in her garden in the 1970's.

My mother had left behind two deaf parents in Missouri who did not understand the uniqueness of a homesteading lifestyle in the hearing world, but her maternal grandparents were acutely familiar with farming.

“My grandparents,” she said, “I thought they would be thrilled because they came from farms ... I thought, they’re going to love this, I’m going to do what they did, and I respect what they did. But they did not understand why anyone would choose to do such a thing.”

Risk of Failure

Not everyone thrived when they attempted to go back-to-the-land. Christopher Hirsch* drove from San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood to Maine with his two brothers in 1969. After a pit stop at the Library of Congress to research “how to farm,” they ended up at a derelict half-acre in the Maine woods that had been used as a trash dump.

“Looking back, it was extraordinary that we were able to clear the trash,” Hirsch said of their first spring in Maine. By the time September rolled around, he and his brothers had been joined by many of their San Francisco friends, bringing along their guitars and psychedelics.

“It just became somewhat insane,” Hirsch recalls. “Several of us had to go out and get jobs because we had to support a larger group.” He remembers a beautiful crop of tomatoes they protected from frost one night by burning old tires. But eventually he realized that his fellow back-to-the-landers “weren’t really interested in living off the land.”

“I decided to leave because the scene became unbearable,” Hirsch admits, and he was not the only one to do so.

“A lot of people lived through the winter and left,” remembers Warren Berkowitz. “It wasn’t without coming and going. A lot of people who read [Living the Good Life] came with expectations that were not going to be met.”

Today’s New Homesteaders

Today, Berkowitz is a steward at the Good Life Center, a nonprofit organization on the former homestead of Helen and Scott Nearing. He lives in an on-the-grid, 1950s house in the nearby town, but remains committed to the legacy of the Nearings.

“Their books still resonate with people,” he said, “People still kind of look at it as a sacred pilgrimage. People who visit literally leave in tears, they are so moved by the place.”

Still, he admits that not everyone was prepared for the challenges of the back-to-the-land lifestyle in the 1970s.

“It wasn’t easy, growing your own food,” he said. “It’s not an easy kind of lifestyle, and I think people romanticized it. We all did to a certain extent. But I think the harsh realities got to a lot of people — in February, when you’re freezing your rear off and it’s not a lot of fun. Most of us came from middle-class, comfortable backgrounds, and it was definitely a step into a lifestyle that wasn’t meant for everybody.”

Barbara Damrosch, in 1977 with a chicken.

Today, self-sufficiency is once again in vogue. After the coronavirus pandemic and ensuing supply chain concerns, many people began to research growing their own food and rural land sales increased. For inspiration, today’s homesteaders turn to organic gardening icons like Eliot Coleman, a now-prominent figure in his own right. He met his second wife, Barbara Damrosch, at the Nearings’ homestead and they married six months later. Between the two of them, they have authored numerous best-selling books on organic farming, encouraging countless others to adopt their methods.

“I feel an obligation to a lot of the people who I visited,” Coleman said. “Who put up with me, put up with all of my endless questions — I’m just paying that back by passing that information on.”

The ‘60s and ‘70s may be long gone, but the desire for self-reliance continues to grow. Today’s homesteaders are less bound together by a common political movement, but they are deeply concerned with the origins of their food.

“Young people are definitely wanting either to farm, or to do something with food,” said Warren Berkowitz. “It’s obvious there is another back-to-the-land movement; I think our kids’ generation is very food-related.”

Kal Winer and Linda Tatelbaum today, still working on their homestead every day.

Don’t Say It’s Over

Winer and Tatelbaum had just finished harvesting their potatoes for the coming winter when I spoke to them. For the 46th year in a row, they’d put up enough food from their garden to feed themselves through Maine’s long winter. Now 75 and 80, they still work on their homestead every day. Their handbuilt house collects electricity from solar panels, but is connected to the grid for the use of a heat pump on chilly winter mornings.

“The question of both of us is how long will our bodies hold out,” admits Winer. “Maybe they’ll hold out for our entire lives, but maybe they won’t.”

“But we are really healthy, and we don’t have any debt.” added Tatelbaum, who still speaks with love about the challenges of homesteading. “I guess some people just got tired of it. But we stayed because we liked it.”

You were participating in your own life. There are plenty of people who are alive, but because of the ease with which they’ve managed to find a space for themselves, they aren’t really participating in their life.

My mother left Addison for a teaching job in a coastal town in the late 1980s. Today she enjoys the comforts of a central heating system, humming electricity, and a nearby grocery store. But she has carried with her from her days in the Maine woods an appreciation for growing food, and in the years since has cultivated a remarkable green thumb. She remembers it fondly, as something that changed the entire path of her existence.

“It was real,” Eliot Coleman said. “You were participating in your own life. There are plenty of people who are alive, but because of the ease with which they’ve managed to find a space for themselves, they aren’t really participating in their life. It’s sort of passing them by, I think.”

*Father of editor Jesse Hirsch