Adopting a wild horse or burro can be intimidating — how do you tame them? But a new BLM grant aims to help with gentling and finding long-term homes.

As a 16-year-old spending her summer working at a ranch in Estes Park, Colorado, Amanda Mills was already familiar with horses, but there was something different about Cricket. Others cautioned her — calling the horse standoffish, skittish. Cricket wasn’t as trusting as some of the other horses at the ranch.

Then Mills noticed a brand on Cricket’s neck, something she’d never seen on a horse. Other ranch employees told her that wild horses receive a brand from the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) when they are removed from the range. Cricket had been born wild.

As the weeks went by, Mills worked to build trust, something that took time and a gentle hand. By the end of the summer, Mills and Cricket had an undeniable bond. Mills took Cricket back to her home in Texas, where they competed together in high school rodeos.

That was in 2000. Nearly 25 years later, Mills is the marketing and operations director at Forever Branded, a nonprofit that helps make wild horse and burro adoption more attainable for the average equestrian, helping BLM-gathered wild horses find their forever homes.

“When I brought Cricket home 24 years ago, I had no idea of how that would change the whole trajectory of my life,” said Mills.

Forever Branded is one of five organizations that all together will receive $25 million over five years from the BLM. The goal of this funding is to help whittle away at the bottleneck of horses and burros that live at BLM holding facilities — over 60,000 animals — stuck in limbo between being wild and finding a secure domestic home. The BLM estimates this award can help place an additional 11,000 horses and burros.

“We are coming at this huge issue, having lived it for a very long time,” said Mills. “We have all seen the good, the bad, and the ugly of everything that has come before, and we’re doing our best to address the problems we know exist.”

The Wild Horse Dilemma

Ten states in the western U.S. have wild horses roaming the range in herds, while five have wild burro populations. The Bureau of Land Management has been tasked with managing the populations of these herds since 1971, when Congress passed the Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act.

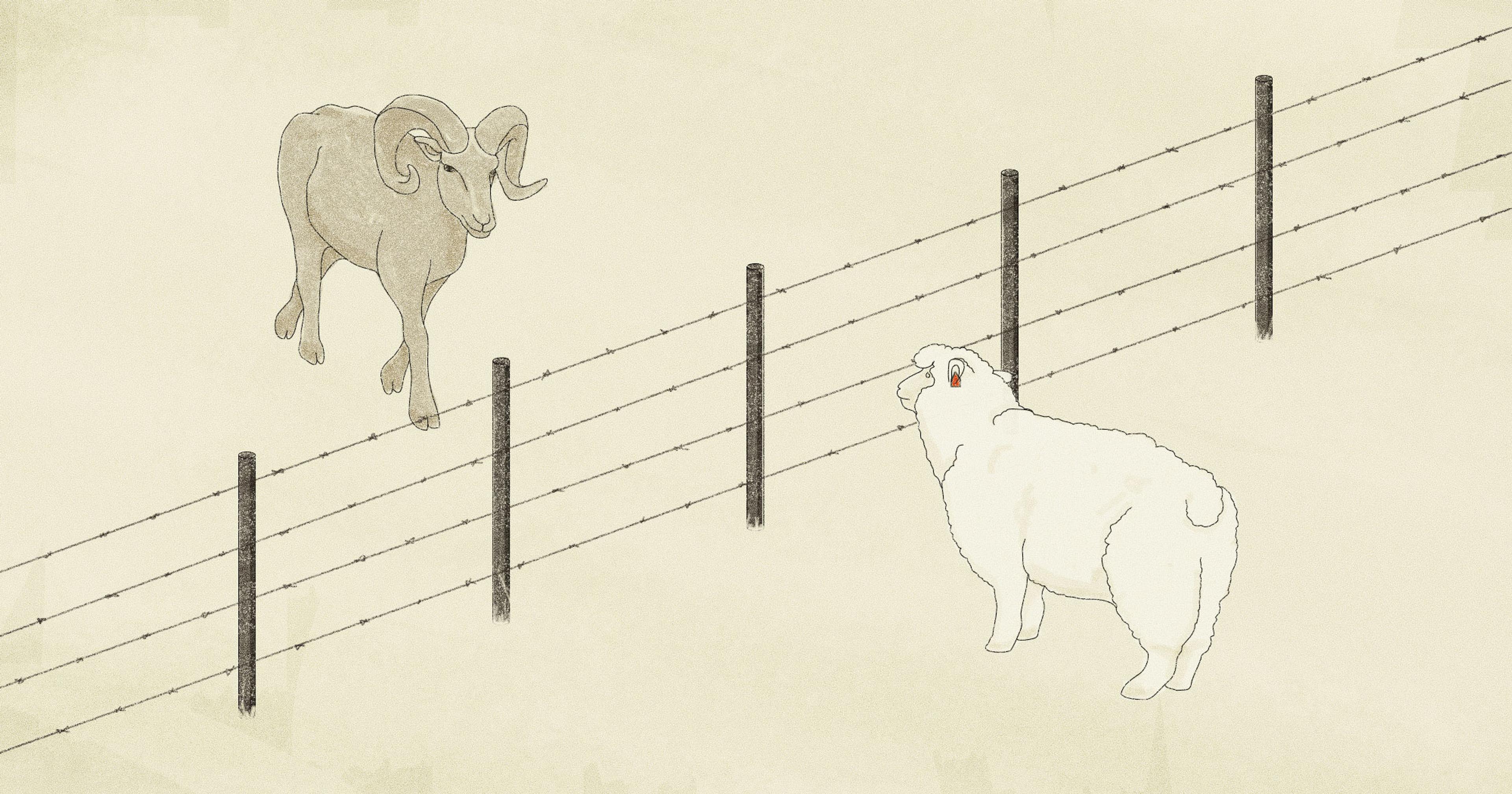

Wild horses and burros reproduce quickly, and predators don’t curb the growth of the population enough. As of 2024, the BLM estimates that there are 73,520 horses and burros in the wild, up from approximately 25,000 in 1971. Each herd management area (HMA) has a BLM-designated population threshold that the area can accommodate. The total threshold across all herd management areas (HMAs) is currently 26,785, meaning there are over 46,000 more horses on the range than the BLM estimates the ecosystem can sustain. A large population can damage rangeland, or outcompete livestock and other wild animals, resulting in depletion of resources and even starvation.

It’s common for state, federal, or Tribal governments to manage wild animal populations. For example, the U.S. Forest Service manages feral cattle with aerial gunners. However, because of wild horse and burro protections, hunting isn’t an option on federal land. And unlike other animal populations that get out of control, like deer, horses can be domesticated.

And so the BLM routinely rounds up wild horses, holding them at facilities until they can be purchased or adopted.

Former wild mustang Remi with trainer Sophia Jasmer Leyenda

·Joan Deutsch

Some animal advocates have taken issue with wild horse round-ups, or the idea of interfering with wild horses at all, since the stress of the horse gathers can cause animals to panic, risking injury and even death. And despite the BLM’s intention to adopt out the horses, some have fallen through the cracks and ended up in slaughterhouses.

Nancy Perry, senior vice president of government relations for the ASPCA said that “some form of management does seem inevitable and necessary to protect these animals.”

The ASPCA vision for wild horses hinges on increasing fertility control, in conjunction with strategic gathering and rehoming of wild horses and burros. Expanding the use of immunocontraceptive vaccines would still require gathers to administer the treatment, but those horses receiving the contraceptive would not be permanently removed from the range. If individualized fertility control programs could be instituted in each region, it would curb the population growth, slowing or eliminating the need for regular horse gathers said Perry — which are risky for horses and expensive for the BLM and taxpayers. Without fertility control on the front end, Perry said the cycle will continue.

“This non-preventative approach will not work. It will just continue to be a spiral of round-ups, removals, harm to horses, harm to landowners, harm to the range, without getting out in front of the problem,” said Perry.

While Perry and the ASPCA are part of those working to end the “spiral” of round-ups, those like Mills of Forever Branded are focused on the other end of the pipeline — removing the barriers to wild horse adoption, and helping equestrians see the potential in these horses.

“You can’t just go in and cowboy the wild out of them. You have to be patient. You have to take your time.”

Forever Branded will use its award dollars to forge partnerships with trainers across the country to gentle horses and pair them with an adopter, easing the transition from the trainer to the new home. It will also create partnerships with private adoption centers in parts of the country that don’t currently receive many wild horses. They will showcase newly trained horses at their Branded Bonanza event, where adopters can see what a trained mustang can do once gentled.

While wild horses have become a cultural symbol, burros often don’t get the same attention. Forever Branded also works with burros, so they can be ready for their domestic life. Mills said her burro is not only a valued companion animal for her, but was her son’s first riding animal, instrumental in getting him into the backcountry at a young age.

Though people can purchase or adopt wild horses or burros directly from the BLM, a major obstacle is that these animals have not been trained for domestic life. The awarded programs create an intermediary step for the horses, one where the horses can work with trainers to be gentled, and transitioned more effectively into long-term homes. The risk of an unaided transition is that the horse and owner don’t click, and the horse can end up back at auction, opening up opportunities for the horse to be put in harm’s way.

“You can’t just go in and cowboy the wild out of them,” said Mills. “You have to be patient. You have to take your time.”

Gentling the Horse

When Joan Deutsch was looking for a new horse for her husband, an acquaintance suggested looking at mustangs. Living in western Washington, they found Remi, a mustang from southeastern Oregon, through Mustang Yearlings Washington Youth (MYWY), a program where trainers spend 150 days gentling a Mustang. MYWY may receive $500,000 over five years.

“We took things slowly,” said Deutsch, now a MYWY board member. “Mike, my husband, worked with him daily … then our trainer and I started working with him to gain his trust. Remi is the smartest, calmest, most expressive and communicative horse we’ve ever had in 40 years.”

Adopted wild horse Remi in action

·Joan Deutsch

Within the equestrian community, the subsect who love wild horses are enthusiastic — but those who are new to the idea of buying one can take some convincing. Joseph Burtard, executive director of Meeker Mustang Makeover in Colorado, said that he never really gave mustangs a chance — until he unknowingly acquired one and found her to be one of the smartest horses he’d ever owned, surefooted and dependable in the backcountry. Now, he’s trying to recruit folks to the program who similarly have overlooked the potential of wild horses. Meeker Mustang Makeover could receive nearly $700,000 over five years.

Burtard’s organization is a nonprofit that supports mustang training through an annual competition. Every year, people who want to train a horse sign up to receive a BLM mustang. In spring and summer, they spend 120 days with the horse, gentling and training. At the end of the summer, the Meeker Mustang Makeover is a competition, wherein trainers show off what the horses can do — after being purchased they may work with cattle, be ridden for pleasure, and more. Though the number of horses per year hovers around 35, the purchase rate is 100%.

Burtard believes programs like Meeker Mustang Makeover can be a good platform for building relationships across different sides of the wild horse issue.

“There’s a lot of wild horses, and removing wild horses from their herd is a very political thing. I think programs like this allows us to find some common ground … this is just the beginning for these wild mustangs.”