A USDA lab devised a way to ID toxins from common poisonous plants using “non-traditional” bodily excretions.

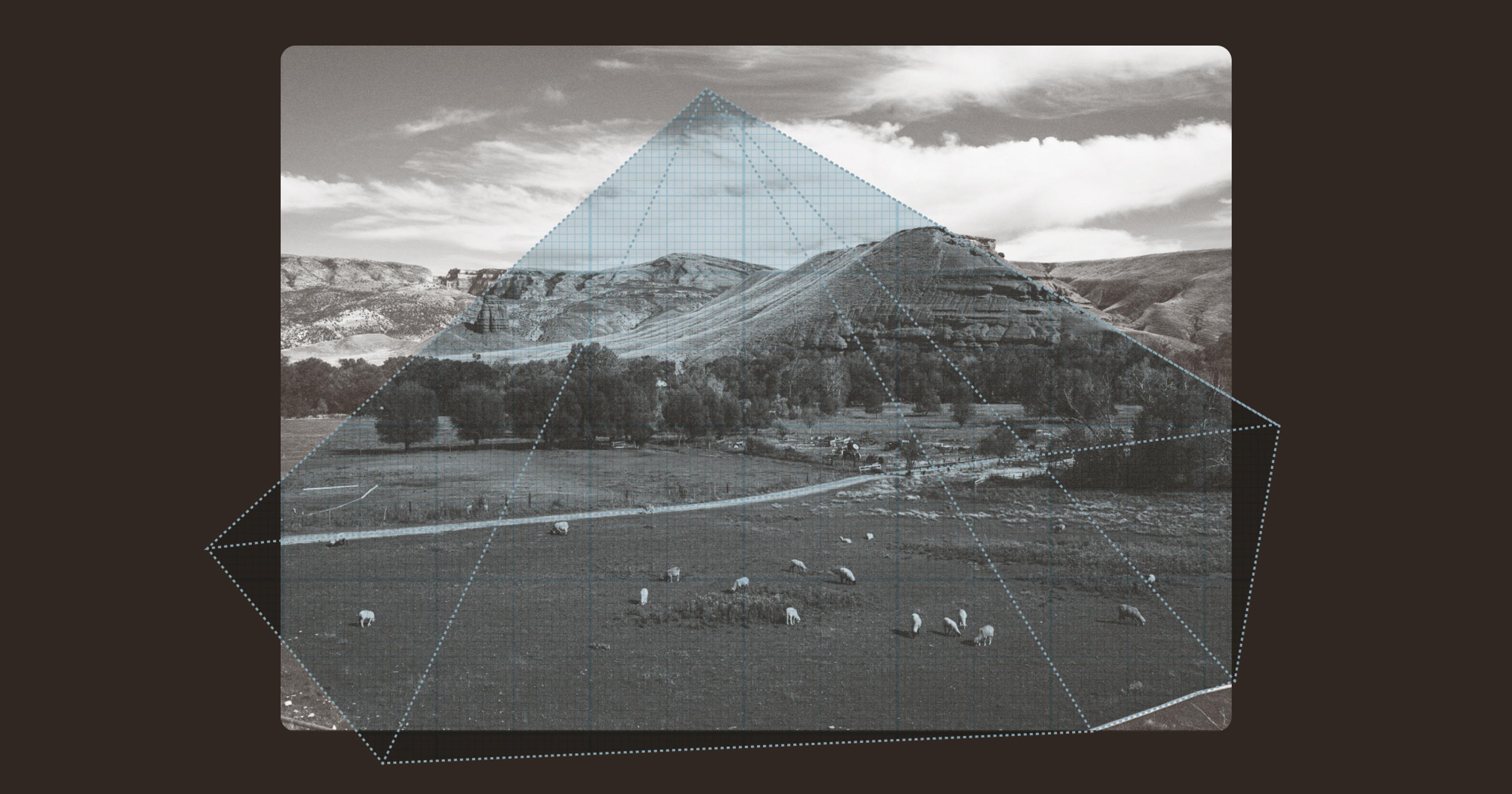

Recently, Raye Walck recounted for this inquisitive journalist a grim story from some high-desert grazing lands in Grand Junction, Colorado. “I had a case a couple of years ago where these sheep came off the range and were brought into a dry lot situation, into a bunch of old pens,” the director of the Western Slope Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Colorado State University (CSU) told me. “There was a ton of kochia weed growing in the pens and they just went for it. There were just piles, honestly, piles of dead sheep.”

Kochia weed is one of about 35 common plants of the Western and Southwestern states that USDA’s Poisonous Plant Research Laboratory (PPRL) identifies as toxic to livestock in a handy reference guide. Although it’s considered more of a problem for cattle, in sheep it can cause dehydration, muscle weakness, blindness, brain swelling, enlarged liver and, if enough of it is consumed, death.

According to Walck, what happened to those piles of sheep was pretty obvious: A visiting extension agent identified the weed and saw that it had been grazed down; Walck sent rumen contents out to a bigger lab to confirm its presence. But evidence of plant poisoning — which costs the U.S. livestock sector about $500 million a year — is not always so easy for a rancher to assemble. That’s why PPRL has been trying to figure out simpler, less invasive ways to identify poisoning, using “non-traditional” samplings like hair, saliva, boogers, and earwax.

The work of PPRL, which has had a home in Utah since 1905, actually began in the late 1800s. American settlers were moving their herds and flocks westward and, unfamiliar with the plants they encountered, began experiencing die-offs. Today, the lab exists in part to educate ranchers about plants of concern — their plant guide can also be accessed as a phone app — and give veterinarians tools to diagnose their ingestion. It’s also looking into treatments for poison-sickened animals; vaccines that might prevent poisoning to begin with (a longshot); and genetic markers that might help breed toxin-resistant animals.

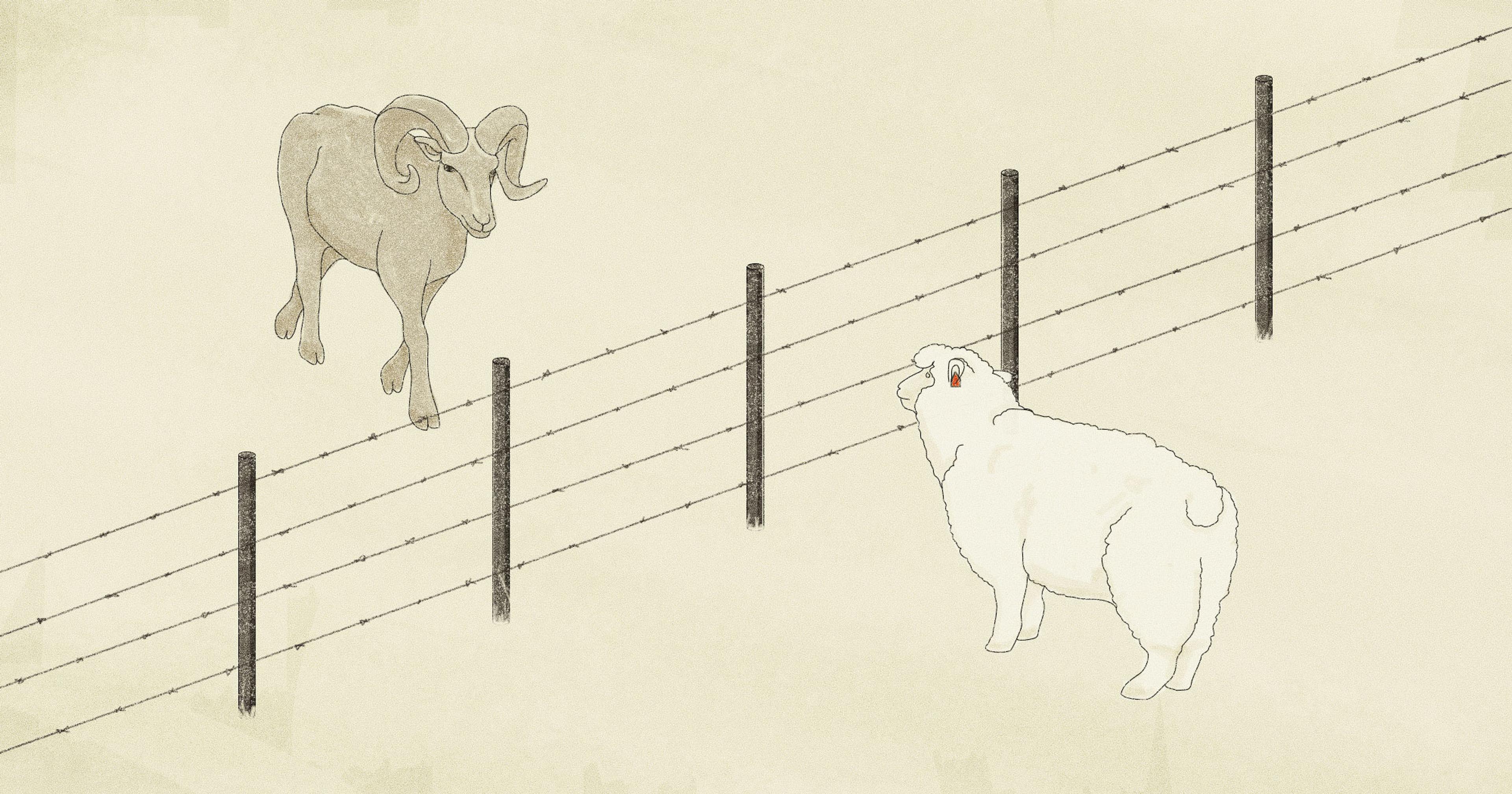

Livestock poisoning affects an estimated 3 to 5 percent of sheep, goats, cattle, and horses every year — a likely undercount since many ranchers won’t bother to report a single dead animal. Although, death’s not the only outcome of some leafy nibbles. Depending on the toxin ingested, at what stage of its growth it was consumed, and how much was eaten, an animal can become painfully ill; a fetus can be aborted; it can give birth to a baby with defects. Most poisonings occur in the 17 Western states because, “In the East, animals are more on [agronomically improved] pastures and they’re fenced in,” said Stephen Lee, a research chemist at PPRL. “And herbicides are more [economically feasible] when you have a couple of acres versus thousands.” Some herbicides may also be forbidden on federal land leased to ranchers.

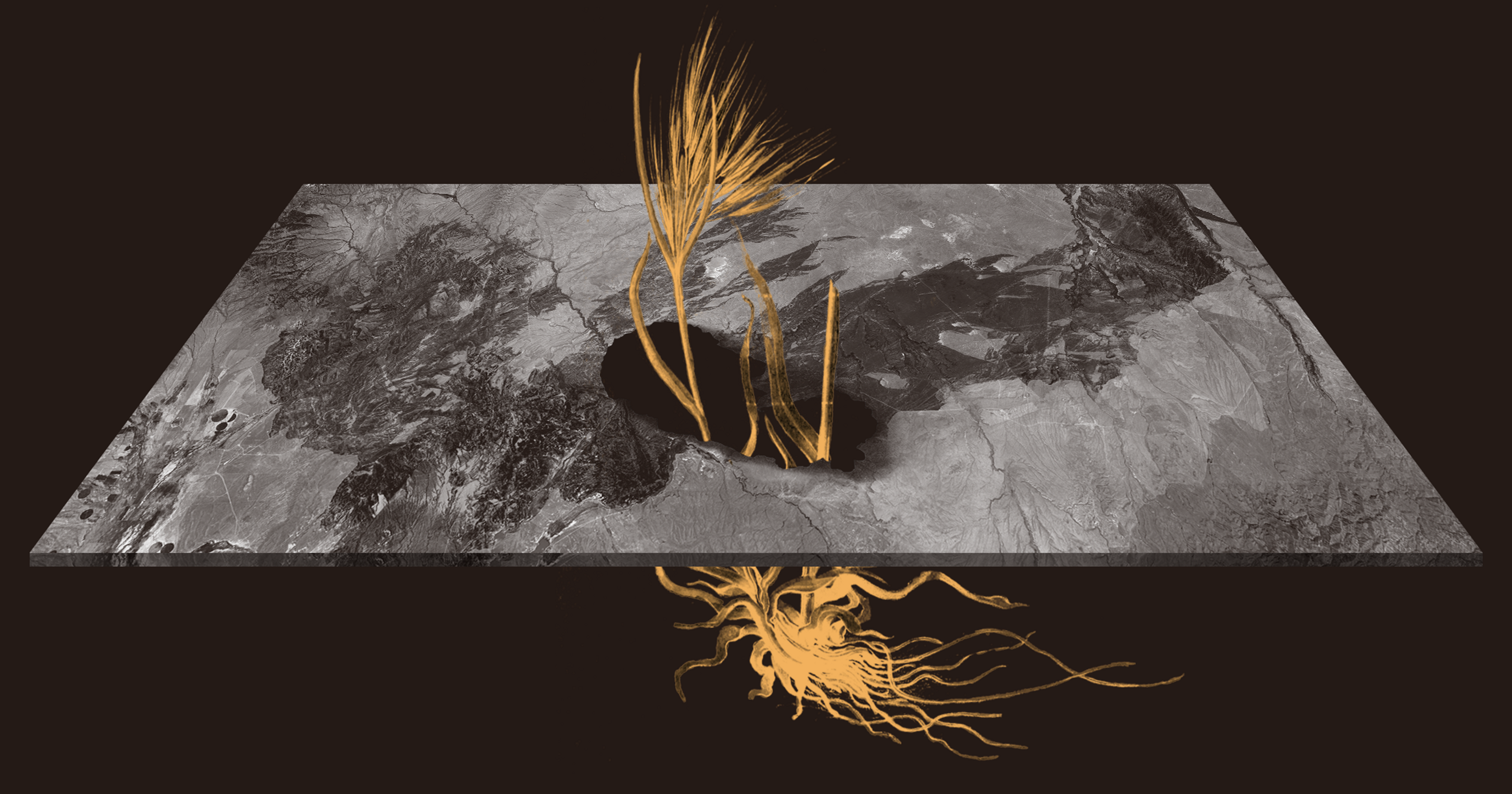

For the past several years, Lee has been testing the effects of some of the West’s most consequential toxic plants: larkspur, locoweed, lupine, and death camas. He’s also trying to figure out if hair, saliva, nasal mucous, or a slug of earwax will contain enough traces to identify the poisons; in all cases, to varying degrees, the answer is yes. “These toxins are in the blood and the blood feeds your glands — they come out in your sweat through your sweat glands, and your saliva through your salivary glands, and the glands in your ear,” as well as the sebaceous glands connecting skin to hair follicles, Lee explained.

These secretions, he said, fill “an important niche. If we have an animal here, and we dose it [with toxin], we can get it into a chute, restrain it, and then” obtain a high-quality blood sample to analyze. A rancher, though, might not have the ability to hold onto a large sick animal out on the range, let alone stick it with a needle. For a dead animal, a sample of stomach or rumen content is preferred by a lab, “But you’ve got to have a knife and it’s stinky,” Lee said. With earwax, for example, “All you need is a tissue and just wipe around in its ear, then put that in a bag and send it to us.”

John Derek Scasta, director of the Laramie Research and Extension Center at the University of Wyoming, likens plant poisonings to bears and wolves: “While they don’t affect every ranch, the ones that they do affect, they can affect significantly.” In his neck of the woods, larkspur, delphinium, and ponderosa pine are problems for cattle; death camas, which he said looks like a small green onion, is a problem for sheep.

“There was a ton of kochia weed growing in the pens and they just went for it. There were just piles, honestly, piles of dead sheep.”

Knowledgeable management is the way to mitigate against potential disaster. For starters, said Scasta, time of year plays a role. During a blizzard, cows — pregnant in winter in advance of spring births — might shelter under a stand of pines, whose needles contain isocupressic acid that causes abortions. In spring, death camas is one of the first plants to sprout through the snow, just as sheep are “foraging around, looking for something green,” Scasta said. They might eat more than usual because they’re hungry, at the time when the plant is most dangerous, although no one’s exactly sure why, according to Lee. At any time of year, sheep can tolerate the toxic alkaloids in larkspur at four times greater concentration than cattle, which is why “Some of the work we’ve been doing is using sheep to graze it before cattle are exposed to it,” Scasta said.

Sometimes the toxic plant isn’t foraged at all. Walck remembers another recent case in which cattle were mysteriously dying in wintertime. Rumen contents were sent out to PPRL, a history of the incident was taken from the rancher, and eventually it was discovered that milkweed had been baled in with their hay. Similarly, said Robert Poppenga, head of diagnostic toxicology at the University of California, Davis, veterinary school, fields might contain high levels of livestock-toxic nitrate after being fertilized — exacerbated by drought conditions — that turns up in oat straw. Sometimes the toxic plant was previously unknown. Scasta recalled a case in which 165 head of cattle died after eating hay contaminated with lanceleaf sage. “That hadn’t even been recognized as a poisonous plant before,” he said.

Sometimes, a rancher is to blame for not adequately surveying his rangeland by photo monitoring or physically visiting established problem areas in the spring; for not knowing enough about the seasonality of toxins; or for not paying enough attention to the broader picture. Steve LeValley is an extension specialist at CSU who’s seen sheep poisoned by a low-lying hairy plant called halogeton. He’s aware of ranchers who set loose from a truck a flock of sheep that’s ravenous after hours of travel. The sheep “just take off and start eating that stuff like crazy,” he said. They might be a replacement flock of “naïve” animals from another state, whose mothers haven’t taught them to avoid halogeton and other poisonous flora of Northern Colorado. “Within 24 hours they can have tremendous death losses,” he said.

Lee believes there’s potential for more poison-related livestock losses, thanks to changes in when and where poisonings are happening. “Climate change is real and our concern is that there is going to be a shift in these plants, into areas that haven’t had problems from [them] before,” he said. As Western state ranchers face the possibility of new toxins requiring their vigilance, Scasta, for one, is glad to know that Lee’s unusual diagnostics could become more prevalent. “We need more tools,” he said, “and innovation is the name of the game.”