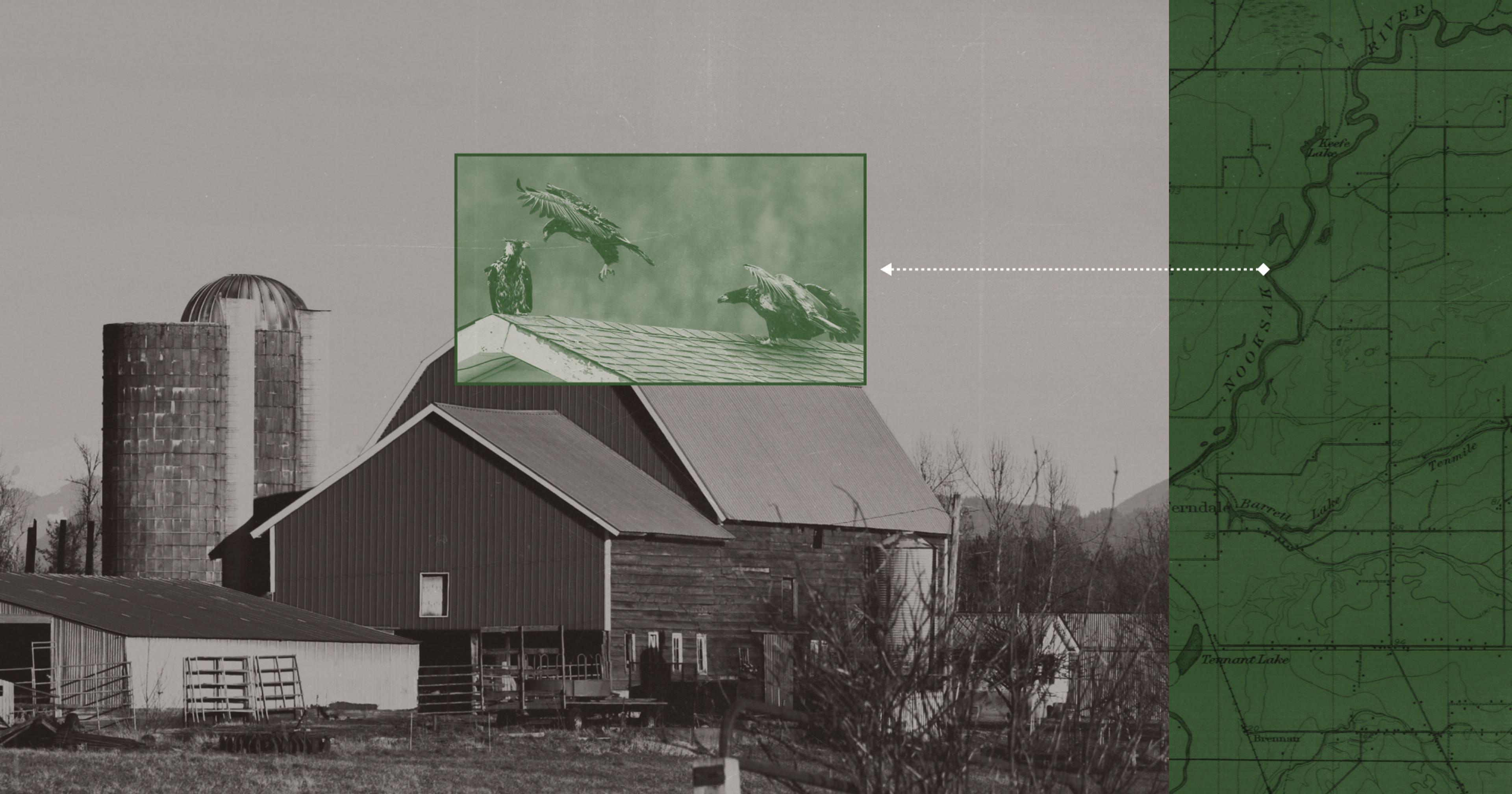

Livestock producers are feuding with black vultures, who sometimes attack and kill newborn cattle. But there’s more to the story.

Bart Jones, a livestock producer on the Kentucky-Tennessee line, says that when his cattle give birth, the vultures are often lurking. The scavenger birds will head right for the fresh afterbirth — as might be typical for a bird that feeds on carrion and other already-dead flesh. But Jones says the birds want a piece of the newborn calf, too.

“We’ll drive up to the field, we’ll see those vultures on the ground and the cow will be circling the baby calf,” he said. “And she’ll be trying her best to protect that baby calf because they will get a baby calf as well.”

Black vultures (one of the three vulture species in the U.S., along with turkey vultures and California condors) live in habitats ranging from forests to grasslands to the suburbs. And in addition to feasting on the rotting carcasses of dead animals, the birds are known to snag a living creature every once in a while, too — including animals that matter to people, like baby cattle.

But scientists say that while black vulture attacks on cattle can happen, the real scope of this conflict still isn’t clear. And it might be in everyone’s interest to keep these vultures — and their ecological role in cleaning up dead animals — around and thriving.

“Having healthy black vulture populations, on the whole, is really advantageous,” said Marian Wahl, a PhD candidate at Purdue University.

Black vultures aren’t really equipped to take down an adult cow or bull, said Wahl. But they’re certainly capable of killing a very young calf — the birds can stand about two feet tall, with wingspans nearly five feet wide, and beaks designed to rip apart soft flesh. For a newborn calf, that can be a sizable threat, especially if they’re facing off against multiple vultures at once.

According to a report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), vultures were responsible for the deaths of more than 24,000 calves in 2015. That would make them the second-most deadly predator of livestock in the country, below coyotes but higher than dogs, wolves, mountain lions, bears, or eagles.

But just because vultures have been blamed for killing a calf doesn’t mean they were actually responsible for killing that calf. Many of the calf deaths blamed on vultures may very well have been stillbirths, Wahl said, with the vultures blamed because the birds had already started eating by the time someone got to the birthing scene. Telltale signs of vulture feeding include damage around the soft tissues of the eyes, tongue, or anus — but even damage to those areas might simply mean that the vultures had started scavenging an already-dead body, Wahl said.

Many of the calves that are killed by vultures are probably those that had a difficult birth, Wahl said, leaving the calf weak or the mother unable to fight off the birds. But determining the true cause of death on a vulture-ravaged carcass can be difficult. Bryan Kluever, a wildlife biologist at USDA, said that scientists can perform a necropsy to determine whether a calf was killed by vultures or died of some other cause, though that necropsy would need to happen quickly.

“When you work so hard to try to get this young calf on the ground and then something or somebody takes it away from you, it hurts.”

“Because [the vultures] feed in these large numbers and they’re so bold, a 24-hour delay and it means they’ve functionally eaten all of the evidence,” Wahl said. (The reason why closely related turkey vultures aren’t often blamed for cattle deaths is that they aren’t as bold as the black vultures, experts said.)

Part of the reason why this conflict has made headlines in recent years may also be that some livestock producers are having to contend with vultures for the first time. Both Audubon and The New York Times report that while black vultures were historically isolated to the southern U.S., they’ve recently moved up into the Midwest, possibly due to climate change.

Yet for many producers, any attack on a calf is a potentially huge loss. “When you work so hard to try to get this young calf on the ground and then something or somebody takes it away from you,” Jones said, “it hurts.” He also pointed out that even just having to defend themselves against the birds could stress out a calf or mother cow, potentially leading to other health issues.

To protect their cattle from vultures, some livestock producers might be tempted to simply kill any roosts that hang out near their fields. But in the U.S., black vultures are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which prevents the unlicensed killing of most native bird species, regardless of whether they’re considered endangered or not.

Some producers can acquire a kill permit, either through the federal Fish and Wildlife Service or select state agencies. But those licenses will probably only allow killing a few birds at a time, and black vultures sometimes roost in groups of dozens.

One bill recently introduced in Washington would make it easier for livestock producers to kill black vultures without a permit. But mass vulture slaughter may not be good for anyone in the long run. While black vultures seem to be thriving, many vulture species around the world are on the razor’s edge of extinction, Wahl pointed out. Some vulture species in Africa and southern Asia have seen their populations drop precipitously over the past few decades, often due to both intentional and accidental poisonings.

Just because vultures have been blamed for killing a calf doesn’t mean they were actually responsible for killing that calf.

And this collapse may come with consequences. In parts of India, local vulture populations started plummeting in the 1990s due to secondary poisoning from a cattle painkiller. Some researchers say that as a result, livestock carcasses piled up, leading to a higher population of feral dogs, which now had plenty of food to eat. In turn, those feral dogs may have helped spread rabies to people across the country.

As Jones noted, livestock producers should have a system to make sure they aren’t simply leaving carcasses lying about their field. But vultures can also clean up dead wildlife that landowners might miss, including roadkill.

“They’re basically nature’s garbagemen,” Wahl said.

And mass killing of vultures isn’t the only option for preventing vulture attacks. To start, producers might simply try to keep a close eye on any birthing cows. This conflict seems to affect pastured cattle more than dairies or feedlots, because the closer the cattle are to human activity, the less likely it is for vultures to attack them, Wahl said.

Of course, keeping an eye on livestock may not always be possible with wider-ranging herds, but producers can make it easier by having a dedicated, scheduled birthing season, she added. Similarly, trained guardian animals can be useful in keeping vultures away.

Fascinatingly, killing one or a few birds — and hanging the dead body up as a warning — might also be effective as a way to scare the birds away. These “vulture effigies” don’t seem to be universally effective, but the birds may take them as a sign that something in the area isn’t safe, Wahl said.

Last year, Wahl, Kluever, and their colleagues published a study that asked livestock producers in Indiana and Kentucky about different vulture management strategies. Sixty-two percent of the producers reported using at least one strategy to deter vultures, most commonly harassment, guard animals, carcass disposal, and moving the birthing cows closer to people.

Simply harassing the birds was not particularly well-regarded — just 47% of the producers who’d tried harassing the birds said that this was effective at mitigating livestock losses. But of the producers who’d tried hanging vulture effigies, 74% said that these gruesome warnings were effective deterrents. In addition, 85% of the producers who used guard animals found them to be effective. Perhaps unsurprisingly, 96% of the producers who’d attempted lethal control of the vultures said that killing the birds was effective at mitigating livestock losses.

Finding a sustainable resolution to this conflict will likely require getting wildlife advocates and livestock producers to work together on solutions, for everyone’s benefit. This doesn’t have to be contentious, Wahl said.

“We have a little bit of a tendency towards this adversarial relationship where we treat it as either protecting wildlife or protecting livestock,” she said. “And we really need to shift the way that we look at things, so that we’re looking at protecting both of them.”