Traditional farm succession planning can be notoriously challenging. Let’s look at the alternatives.

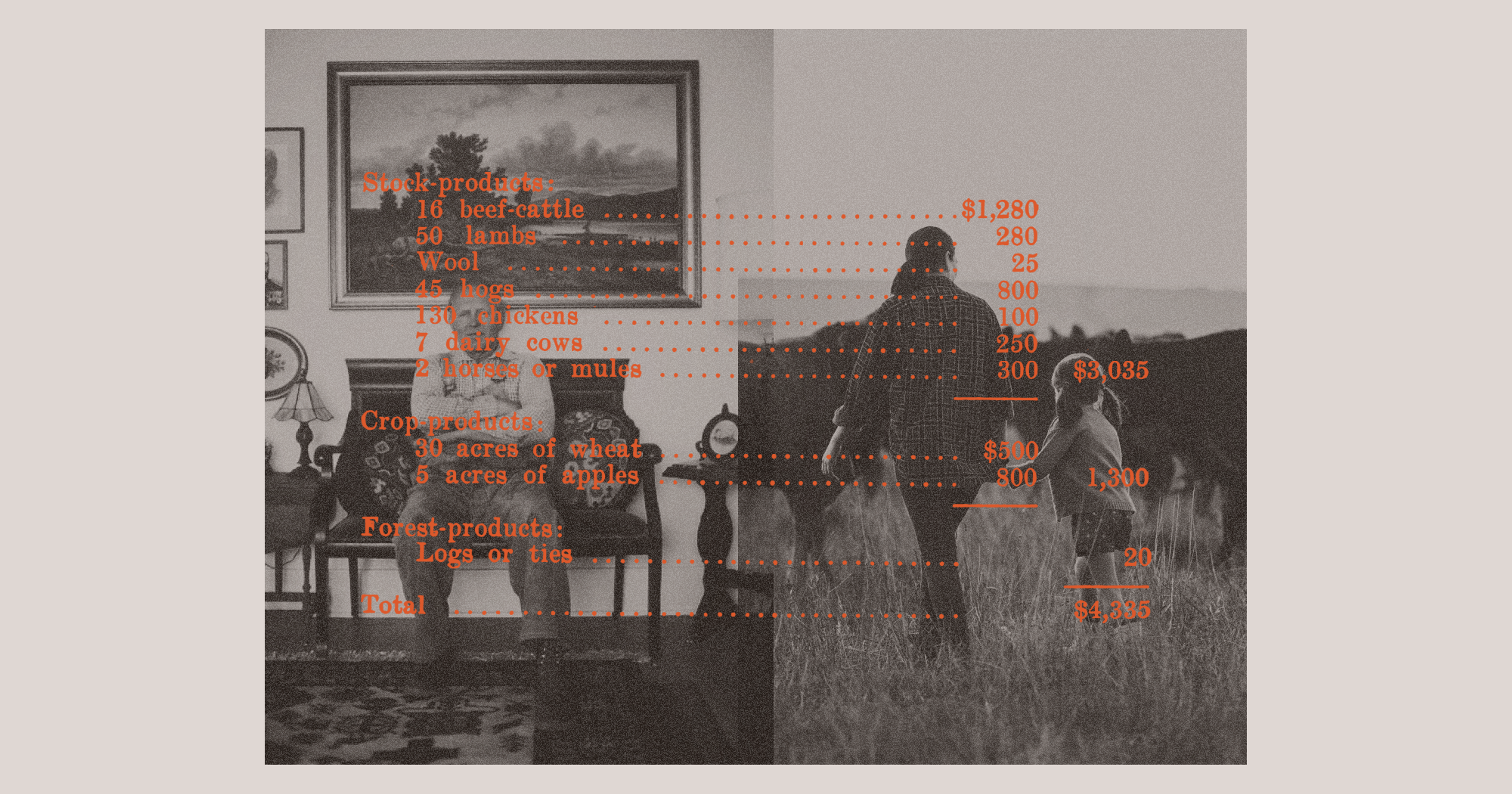

Myron Edwards’ Clover Hill Farm in Cleveland County, North Carolina, has seen a lot of change over the 160 years that his family has owned it. Before Edwards took over the farm from his ailing father in the ‘70s, the business had transitioned from a cotton cash crop to beef cattle, soybeans, and grains. From an original size of about 1,000 acres, the land at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains was steadily sold off until it reached its current size of 192 acres. “This is the last of the last,” Edwards said.

But perhaps the biggest change came in 2017, when Edwards, now 72, put the land in a conservation easement, an agreement between a landowner and a land trust or government agency, designed to protect the land from future development. In most cases, the agency or trust purchases the development rights — leaving all other property rights in the hands of the farmer — at a lower rate than the market would dictate. When the farmer passes on, the land, now protected from development in perpetuity, can then be sold at that more affordable rate to future farmers. Edwards neither married nor had children, so he had no direct heirs.

“I thought that was the best way that I could preserve the land and the place here and keep it free for future generations,” he said. He even donated a portion of the land, as many landowners do, to lower the total cost for the conservation agency.

Whether an aging farmer has no kids, kids who don’t want to farm, or kids who want to farm in new ways, succession planning is often tough. Andrew Branan, an agricultural lawyer who now serves as extension agricultural and environmental law specialist and associate professor in agricultural and resource economics at North Carolina State University (NCSU), said farmers often fear that the land will no longer stay in the family to be farmed as earlier generations did. As Maureen Purcell, an only child who will inherit her father’s Wisconsin dairy farm wrote here, “At times, the land and the tradition of farming feels like the only connection I have to my family: my immediate family and my ancestors.”

To address this issue, land-grant universities, nonprofits, and government grants are emphasizing alternatives to traditional land succession from one family generation to another. Conservation easements, which first arose as a means of protecting wildlife habitat in the 1930s, are increasingly being used to protect farmland from development. More recent programs like NCSU’s FarmLink and LandLink in Maryland’s Montgomery County stem farmland loss by matching landless farmers with agricultural landowners. But these methods are not without their challenges, especially when it comes to building bonds across generations and across bloodlines.

A Matter of Trust

For Edwards, a conservation easement that would keep his land in farming offered a relatively straightforward solution to the problem of having no heirs. Even so, the process took a couple of years. “It’s not a fly by night thing,” Edwards said. He worked with Foothills Conservancy of North Carolina, which has conserved over 68,000 acres in eight counties across Western North Carolina since 1995.

According to stewardship director Ryan Sparks, the most common cause for delay is the funding process from the North Carolina Agriculture Development Farmland & Preservation Trust. Applications can only be submitted once a year, and they require a significant amount of documentation, from property deeds to land surveys and conservation plans. Easements that pursue additional federal funding can take even longer, due to a backlog of applications and short staffing.

Still, organizations like Foothills find working with farmers on their own can sometimes be much smoother than working with farming families. Sparks recalled a recent visit to check on a recent easement where the children, including a son who worked on the farm, “didn’t know a lot about the easement and didn’t know a lot about the process.”

For farmers who either have no children or know their children will not want to farm, there are other options. Jess Laggis, farmland protection director of the Southern Highland Appalachian Conservancy (SAHC), which has conserved over 80,000 acres in Western North Carolina and Eastern Tennessee since 1974, has found two particular models of land transfer to be particularly helpful.

“None of this land is meant to be in people’s families forever.”

The first is a deed of trust, in which land ownership is transferred before the full amount is paid. Laggis noted that two families in Sandy Mush, a township outside of Asheville, North Carolina, used this means to transfer land. Once the deed of trust was recorded at the courthouse, SAHC could pursue an easement with the new owners. Using the compensation they received from the state for relinquishing their development rights, they were able to pay it off.

Laggis stressed, however, that a deep connection between the families already existed. “These families had known each other for years and had the faith that they would be paid back,” she said. Even though the land reverts back to them if the new owners fail to pay the full amount, landowners may hesitate to enter such agreements if they do not know a farmer and their operation well enough to be certain it will succeed.

The other model of land transfer is a straight bequest of the land to SAHC after a farmer’s death. Since Laggis began her tenure in 2018, two farmers without children — both still living — elected to do this. For farmers who do not need compensation during their lifetime, bequests avoid the work of applying for an easement, leaving that task for the conservancy to complete as the ultimate landowner.

“We don’t try to acquire farmland for the most part, because of the maintenance, because we don’t have the staff capacity to farm it, because then we need to find farmers,” Laggis said. Current plans for these bequests include expanding the acreage of their Farm Incubator Program, where beginner farmers can spend up to five years gaining experience, or selling the land outright to beginner farmers at greatly reduced rates.

Convincing Legacy Landowners

Andrew Branan has worked on intergenerational farmland transfer since 2003, including through his own agricultural law firm. Now at NCSU, one of his jobs is to introduce landowners to options beyond familial land transfer.

In information sessions he calls “land summits,” Branan joins tax officials and energy company employees to present on a variety of topics to farmers. His role, he says, is to speak to legacy landowners like Edwards, whose land has been in the family for generations, about land succession. Some families can trace their land back all the way back to King’s grants in the late 17th century. As a result, they struggle to reconcile the desire to keep the land in the family with the desire to keep it farmed if their children want to pursue other professions.

Branan’s task is to get them to see it differently. “None of this land is meant to be in people’s families forever,” he tells them. “You’ve got a lot of youth … out here that wants to farm the same way your grandparents started out. Give them a chance.” He advises these families to cut off a manageable parcel of land, about 25 acres or so, to either sell or lease to a younger or beginner farmer.

“It feels like stretching your hand into the future and saying, do these things as I want them done.”

How many farming families take him up on this offer, however, is open to question. “Frankly, this is a theoretical suggestion,” Branan admitted. Branan’s colleague, Stephen Bishop, NC FarmLink director for the western half of the state, could only recall one farmer who had considered doing so. However, when we reached out to her, she explained that, though she and the prospective farmer appeared to share ideas about how to steward the land, their practices ultimately did not align, and the collaboration subsequently fell through.

“That just goes to show how delicate and tenuous farm succession scenarios can be,” Bishop commented via email. Even so, he pointed out that unsuccessful matches can help young farmers clarify their goals and older farmers better understand the legacy they want to leave. “That’s why it’s so important to start succession planning early — it will often take years to know whether or not the process was successful,” he added.

Unease With Easements

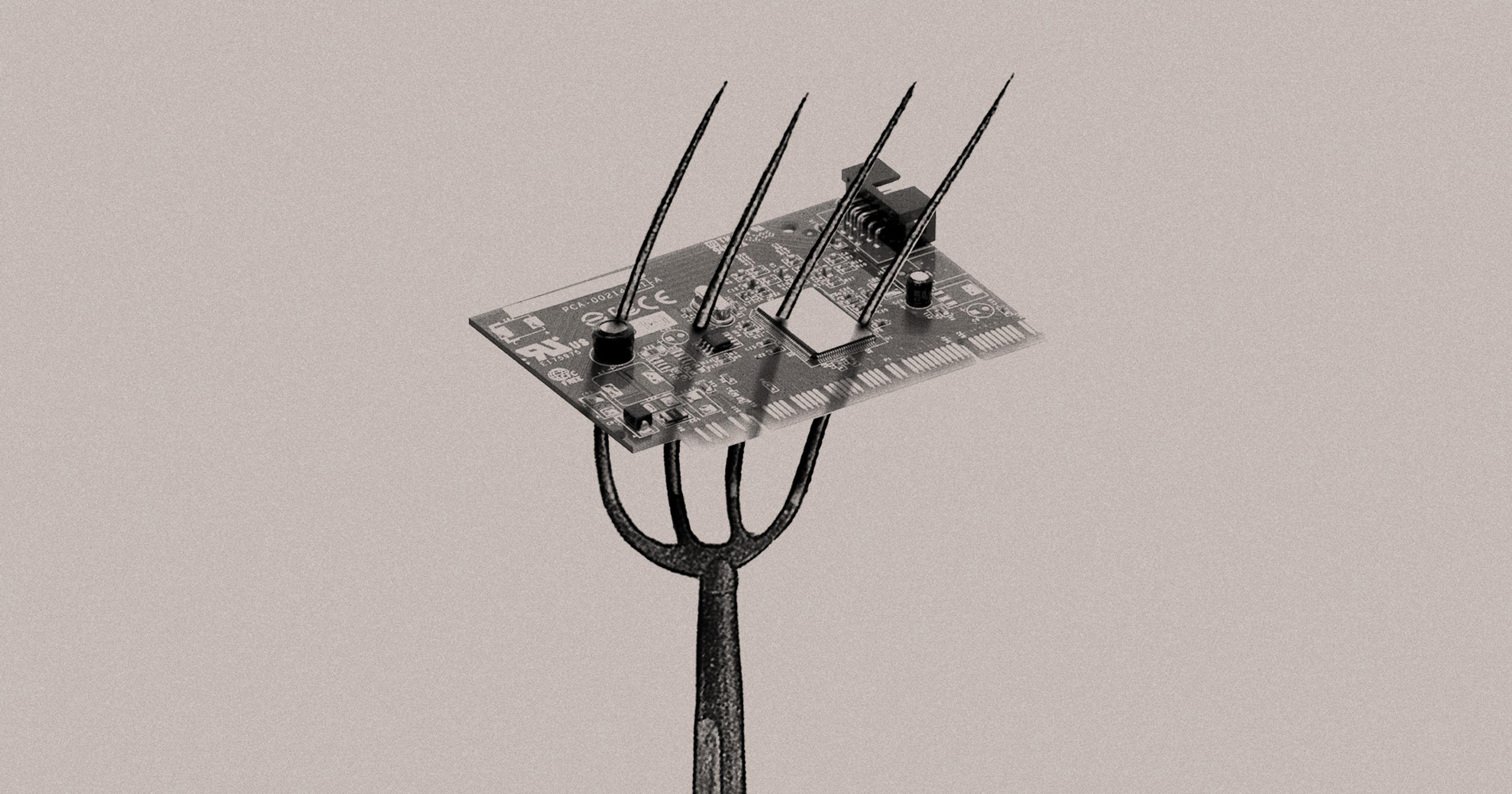

Journalist-turned-farmer Beth Hoffman and her fifth-generation farming husband, John Hogeland, initially planned to invite a young farming couple to come work a small plot of land on their farm in southwestern Iowa. However, they quickly realized that the learning curve was too steep for a young farmer to immediately start producing on land they had no experience with. “There’s no other field that we expect people to go from intern to, you know, owner,” she said.

Instead, they have hired a couple to work and live on the farm, which sells grass-fed beef and goat, so that they can get to know the current livestock operations on the land. Moreover, it allows both couples to figure out if their visions and values align.

“I’m obsessed with thinking about who’s going to get the farm,” Hoffman said. While she sees the benefits of conservation easements, she personally feels uncomfortable with setting constraints on how land should be used without knowing what the future holds. “It feels like stretching your hand into the future and saying, do these things as I want them done,” she said.

As an alternative, she is in conversation with the nearby Meskwaki tribe, a nation that has successfully reclaimed land since the mid-19th century and is considered a leader of #Landback, a movement focused on tribal land reclamation. It’s not as simple as giving them the land, however. The tribal members have to conclude it is in a location and has qualities that they would want.

“I would love for it to be ultimately like its own business entity, nonprofit entity, trust entity,” Hoffman said of the farm. Exactly what that entity will look like, however, she does not know.

A Changing Future

Innovative approaches to farmland succession will continue to arise in the coming years. They will have to, Hoffman suggested, as the growing impact of climate change puts unprecedented pressure on the social order. Put simply, she does not trust existing structures like easements to “safeguard everything when everything turns sour.”

Laggis, too, has changed her language when she described easements. “I used to say forever. I try to hedge that a little bit now,” she said.

Demographics are also changing. According to the 2017 Census of Agriculture, the average age of the nation’s 3.4 million farm producers was 57.5 years, up from 56.3 years in 2012. With family farms making up 96% of all farms in the U.S., intergenerational land succession will continue to raise the kind of thorny questions facing Purcell as she prepares to inherit her father’s farm.

Yet, as Edwards’ case shows, a respect for family tradition can be the motivation to look beyond blood when transferring land. “The reason I [did] it is because it’s family land, you know, and it’s been in the family so long,” he said. “It kind of sounds noble, but shucks — you know, I just wanted to do what I needed to do to protect it.”