New communities offer residents the perks of a farm in their backyard, while someone else handles the labor. What happens to the farmers who work there?

When Arizona native and former farmer Kelly Saxer was ready to reenter the agricultural world after having a child, she reached out to a workplace with a rather dreamy name: Agritopia. Founded in 2005, the 160-acre community in Gilbert, Arizona, is located on a former farmstead and is the result of a collaborative effort between the Johnston family, the town, and developers. For residents, Agritopia essentially offers a farm in your own backyard — while someone else does the work of farming it.

Having farmed nearby from 2001 to 2014, Saxer knew the farm offered its employees a built-in clientele of residents who purchase CSA boxes and patronize the neighborhood’s restaurant and cafe, supplied by the farm. “There is a good population of people immediately around the farm to provide a solid customer base,” she said.

Welcome to the seemingly idyllic world of agrihoods. In its 2018 report Agrihoods: Cultivating Best Practices, the Urban Land Institute (ULI) defines these planned developments as “single-family, multifamily, or mixed-use communities built with a working farm or community garden as a focus.” The institute estimates that more than 200 agrihoods currently exist in the United States. Like any development, they come in all shapes and sizes — urban, suburban, and rural. Many include farms, but some offer only community gardens. Rancho Mission Viejo in California even boasts a cattle ranch.

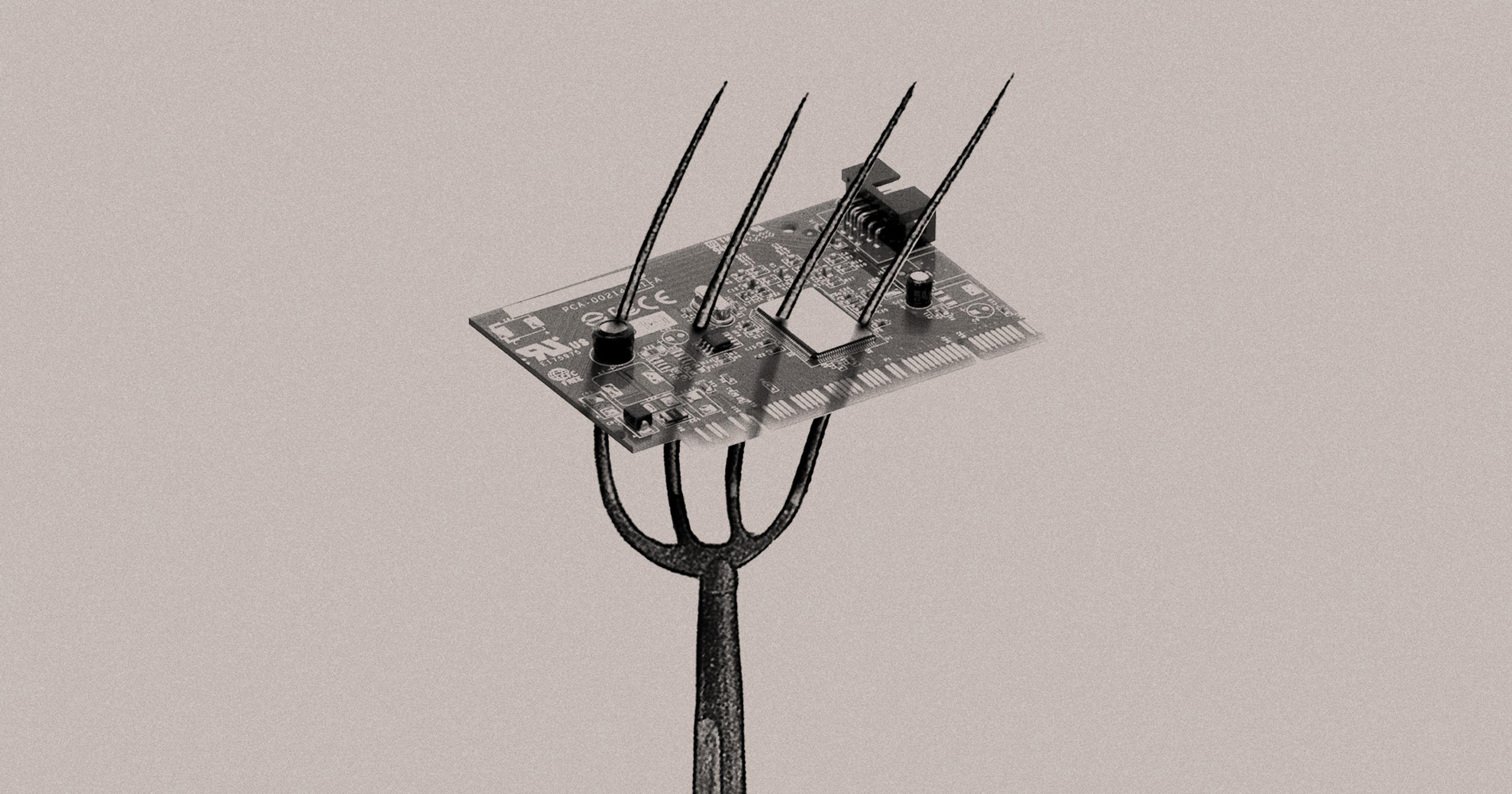

Daron Joffe, founder of Farmer D Consulting and a contributing author of the ULI report, says agrihoods fall on a spectrum: On one end are developments that include a community farm primarily as a marketing tactic to sell higher-priced homes. On the other are developments that prioritize land conservation and work with local governments and nonprofits to provide healthy local food to residents and the wider community. Some agrihoods charge homeowners one-time or annual fees to support the farm — but plenty of them don’t.

“Everywhere and anywhere we can incorporate more farms and gardens in communities, it’s a good thing,” Joffe said. “But it can also be a greenwashing thing.”

Most agrihood stories focus on real estate concerns, especially affordability and equity. Yet the experience of farmers has been overlooked, even though they are arguably the most vital component to making an agrihood work.

“It’s a great career pathway for people interested in agriculture,” said Joffe, who adds that farmers can often make as much as, if not more, working for agrihoods than working on traditional farms. He also stressed the community ethos that agrihoods can create. “It creates jobs in the ag field that are less isolated, more community connected, less risk.”

Community, Consistency, and Clientele

On the French Broad river, 6.7 miles from downtown Asheville, North Carolina, sits Olivette Riverside Community and Farm, a 411-acre agrihood with miles of walking trails, community gardens, an outdoor pavilion, and even a goat paddock for the residents living in geothermally heated and cooled homes.

The heart of the development is the 5-acre Olivette Farm, managed by married couple Daniel Pettus and Lauren Penner. Residents can buy a traditional CSA box or use a prepaid card to purchase organically grown vegetables a la carte.

Most farmers in agrihoods — including Pettus, Penner, and Agritopia’s Saxer — are salaried, offering a more stable income than owning their own independent farm business. In some cases, this structure frees farmers to focus more on the farming itself. Carol McQuillen, co-founder and director of nonprofit Common Roots, which runs the farm at an agrihood in Burlington, Vermont, called South Village, said this is also the kind of support she hopes to provide. “We do things like manage the finances and plan the marketing that farmers would have a hard time doing all within themselves if it were simply a family farm.”

While Pettus and Penner are responsible for creating their yearly budget, they like the autonomy that the developers give them. “We’ve come to learn that it’s actually almost like having our own farm, and we treat it that way,” said Pettus.

“It’s a really independent situation that we have here, which is something that Daniel and I thrive in,” Penner added.

For all of these farmers, working within a community makes a real difference. “Farming is a challenging career, and I think [doing it] in isolation can be at points really difficult,” said Pettus. When an Olivette resident drives by the farm – which sits right near the entrance to the community — and thanks him and Penner for their work, it mitigates the everyday stresses of farming. “It’s just an added benefit that I think a lot of farmers don’t get to hear,” he said.

Trouble Putting Down Roots

Yet there are challenges that come with farming an agrihood, beginning with decisions made long before farmers ever arrive. “Developers aren’t usually farmers,” Joffe said, and they may not set aside the most fertile land for agricultural use. The farmland at South Village is an example. “It’s really not a farm that a single person could easily make a living off [of] because the land base with heavy clay is not that phenomenal,” said McQuillen. To supplement the farm, Common Roots set up the Farmstand store, where residents and non-residents can shop for fresh, organic vegetables in the neighborhood. The majority of the farming occurs on four nearby acres.

“The size of the farm is a really important piece to the Agrihood puzzle,” said William Johnston, CEO of Agritopia. “If we could go back, we might modify some of the layout of the row crop parcels, but all in all, the size (11.5 acres) seems to be good,” he added.

At Agritopia, the farm was always central to the vision because the Johnston family had owned and farmed the land since the 1960s. As Saxer noted, however, its urban location presents a challenge when it comes to equipment. “Designing an urban farm around nearby housing, it’s important to ensure there is ample room to maneuver machinery,” she said.

Machinery has been an issue for Pettus and Penner as well. Pettus recalled worrying about disrupting the residents when using the tractor late on weeknights. He and Penner are also careful not to leave equipment in unsightly piles. “We have an audience,” as Penner put it.

Ironically for community developments, the biggest challenge for many farmers is housing. Saxer lives in an apartment complex across the street from Agritopia, and Pettus and Penner rent a nearby house from an acquaintance, at prices comparable to the area. McQuillen especially attributes the high turnover of farmers at South Village over the last decade to a lack of affordable housing. However, Common Roots is working on this issue, and she said that the current farmer at South Village “will be the first farmer coming back a third year because he knows we’re working on farmer housing.”

Future Potential

Joffe believes the future of agrihoods lies in the growing involvement of local governments, creating public-private partnerships with developers and nonprofits. “We don’t really support the culture side of agriculture. It’s more the production side,” Joffe said. “And I think we’re missing a huge opportunity … If we really want to make an impact, and do it quickly, I think it has to be at the county level.”

Ben Breger, a transportation planner in Northampton, Massachusetts, who completed his master’s thesis on agrihoods in 2020, agrees. He emphasized the power of local governments to incentivize farmland preservation and affordable housing in agrihoods through zoning requirements and density bonuses.

However, Breger also suggested that a think tank like the Urban Land Institute should consider not just suggesting best practices but putting together certification guidelines. Potential requirements Breger would like to see include mixed-income and multigenerational housing, permanently protected farmland, and a requirement for planting or producing a certain amount of food per acre.

For both residents and the farmers, however, the power of community emerges as one of the most promising aspects of agrihoods. “The farm was definitely an aspect that drew us to the neighborhood. However, the neighborhood’s ethos of knowing your neighbors on a deeper level and having everything at your front door was the real reason why we landed here,” said Katie Critchley, an Agritopia resident who is now the farm director for the Johnston Family Foundation for Urban Agriculture. Many agrihoods incorporate frequent community events, from dinners to holiday celebrations and even educational classes like cooking and foraging.

At Olivette, residents see Pettus and Penner working long and hard every day to grow food for the community. Penner is glad that her work is so visible: “They see what it takes for this food to get to their plate and they have a greater appreciation for it.”

Disclosure: Ambrook has consulted on branding for The Agrihood Collective, a group which Common Roots belongs to.