States are trying — and in some cases, succeeding — to allow teens to work longer hours and in dangerous environments.

This past May, Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds (R) signed into law a bill that would sharply decrease protections for child workers in her state, while making it tough to impose penalties on employers for related violations. Touted by supporters as a way to address Iowa’s labor shortages — and afford kids “valuable” work experience — starting the first week of July 2023 it opened the door for meatpacking plants to hire apprentices as young as 14 to work on meat processing lines, for example, as well as for kids to work 6-hour night shifts during the school year.

As this bill made its way to the governor’s desk, 13 other states have introduced — and in some cases advanced — similar rule-loosening pieces of legislation. Meanwhile, concerns about the dangers posed to kids placed in high-risk work environments have been brushed aside. What could possibly go wrong?

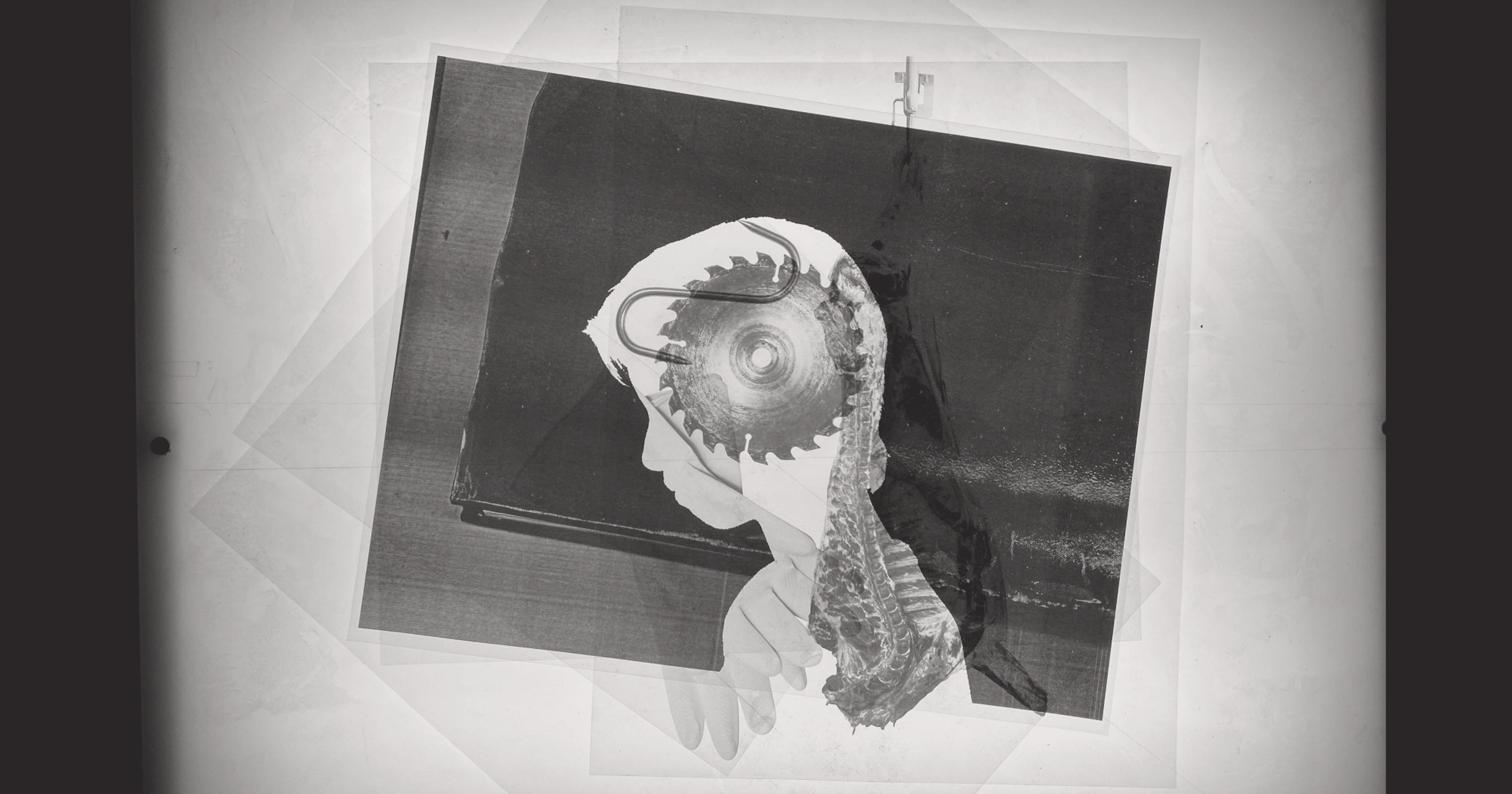

At least part of an answer came as Iowa’s new law took hold, when a 16-year-old worker was killed in a sawmill accident in Wisconsin. And a Michigan meat processor just pled guilty to hiring a 17-year-old who lost a hand as he operated a meat grinder while under supervision — a stark rebuke of the notion that adult oversight can prevent injury in hazardous work environments.

Although the hiring of child workers in both cases contravened laws in their respective states (as well as federal law), these incidents serve as potential omens for Iowa, as well as Arkansas, which is getting set to implement its Youth Hiring Act to remove “arbitrary burdens” to parents around obtaining working papers for kids under 16. And while that may sound less fraught than what Iowa’s about to do, it sets a precedent. “Without work permit requirements, companies caught violating child labor laws can more easily claim ignorance,” points out Fortune magazine.

Whether they’re hired legally or illegally, anyone under the age of 25 is twice as likely to be injured on the job as those 25 and older, according to OSHA. Such stats prompted U.S. Solicitor of Labor Seema Nanda to tell States Newsroom that it’s “irresponsible for states to consider loosening child labor protections.” Instead, “federal and state entities should be working together to increase accountability and ramp up enforcement,” she said.

Since 2021, 14 states have loosened their child labor laws, or tried. New Jersey has permanently increased summer working hours for 16- and 17-year-olds to 50 hours per week, and for 14- and 15-year-olds to 40 hours per week; it’s also abolished the need for parental consent for working papers. New Hampshire has done away with a prohibition on night shifts for 16- and 17-year-olds and extended their school year work hours to 35 per week; it also lowered the age when kids can bus restaurant tables served alcohol, from 15 to 14. And Michigan has lowered the age for serving alcohol and working in liquor stores. These loosenings have been billed as a way to address our post-pandemic labor shortage.

Lawmakers in Ohio, Missouri, Wisconsin, and South Dakota introduced bills to try to increase work hours for kids; some of these are still pending. Maine, Nebraska, and Virginia all took a shot at paying minors less than minimum wage. Georgia legislators tried to do away with work permits for kids under 18 and to make it legal for 14-year-olds to operate lawn and garden-care machinery. And Minnesota legislators want to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to work in construction, the 15th most dangerous industry, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor and Statistics. Meanwhile, over in Congress, the Future Logging Careers Act introduced by Senator James Risch (R-ID) seeks to make it federally legal for 16- and 17-year-olds to work in logging, America’s fourth most dangerous job.

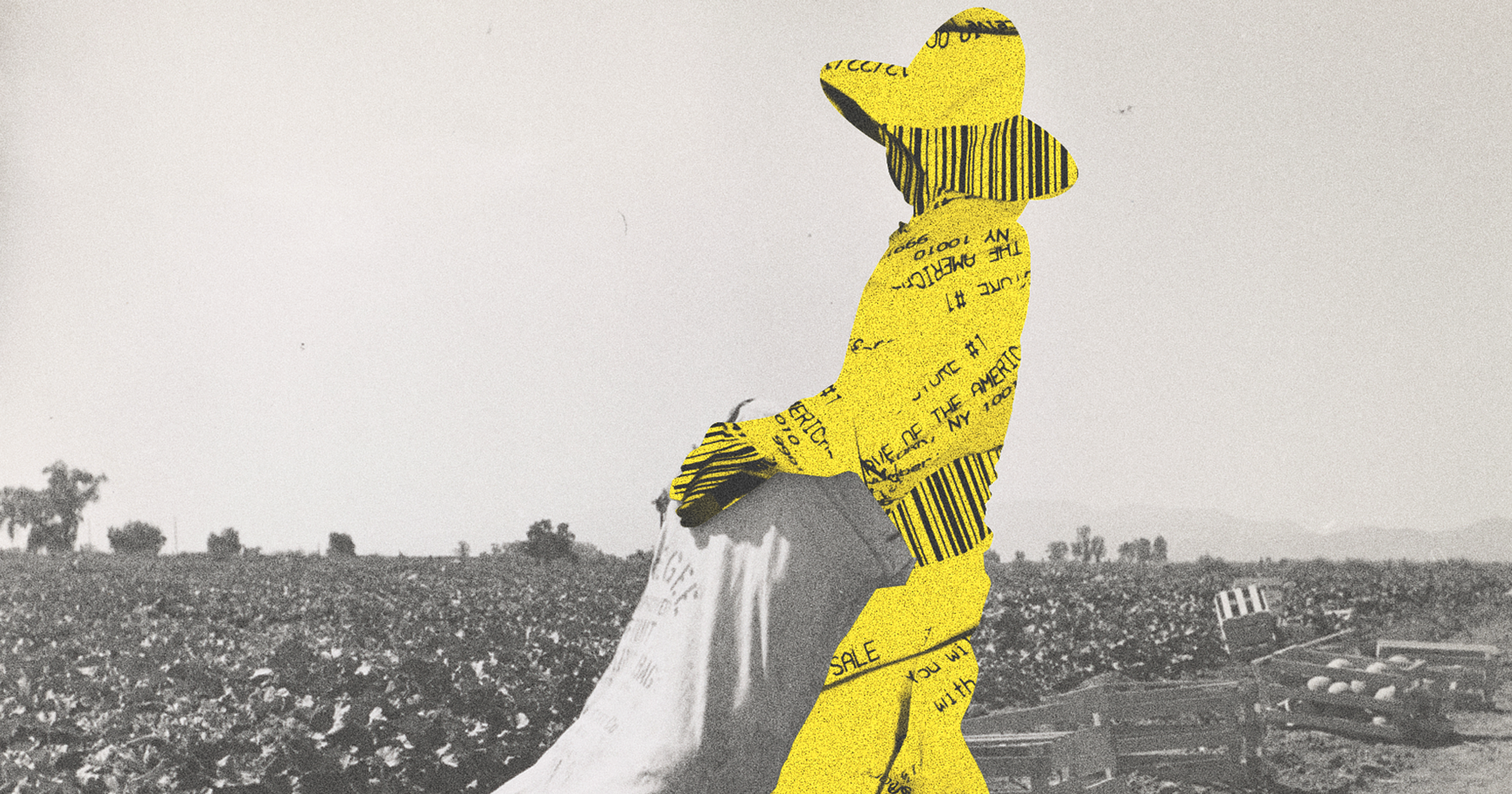

Labor experts say there is a throughline between these child labor law rollbacks and the agriculture sector.

Labor experts say there is a throughline between these child labor law rollbacks and the agriculture sector — the third most dangerous industry in the U.S. — where federal exemptions have long allowed kids to perform a range of risky tasks like operating heavy machinery. The U.S. General Accountability Office says it’s by far the most deadly profession for children.

“Look at what’s happening in U.S. agriculture: It’s a preview of what is going to happen if these [new state] laws remain in effect,” said Margaret Wurth, senior researcher in the Children’s Rights Division of Human Rights Watch. “Kids are going to get killed at higher rates. They’re going to be exposed to repetitive motions and heavy labor that can affect their developing bodies. They’re going to be exposed to toxic chemicals that can affect their developing brains.”

As many as 500,000 children, some as young as 10, work on U.S. farms, according to the Association of Farmworker Opportunity Programs. Health threats to this group come from extreme heat, pesticide exposure, and most of all farm machinery. As AFOP reports, about 20 percent of all farm fatalities occur among children — some 300 kids in agriculture die per year — and more than 10,000 kids aged 10 to 15 incurred on-farm injuries in 2006.

Of course, not all farmwork is dangerous. Many would argue the agricultural labor exemption exists to benefit farm families who are teaching their children a valuable trade and getting some valuable help all at once. At a 2022 Congressional hearing on reforming agriculture’s child labor laws, agricultural policy attorney — and former farm kid — Kristi Boswell warned that the exemption helps preserve an invaluable way of life. “My niece and nephews would not have been able to detassel corn at ages 12 and 13, despite their parents knowing they were mature enough to handle the job,” Boswell said in her testimony. “It is critical now more than ever that our policies develop our next generation of farmers and ranchers, rather than discouraging them.”

Outside of agriculture, labor experts express concern that loosened laws in Iowa, Arkansas, and wherever else they pass will make these populations even more vulnerable. That’s because they may prove the most likely to accept this kind of work, and the least likely to push back against long hours, low pay, and dangerous conditions.

“Instead of strengthening our labor laws and protecting workers rights, we’re putting kids at risk.”

“They have families who are very poor” and they take jobs “out of desperation,” Reid Maki, director of child labor issues at the National Consumers League’s Child Labor Coalition, said in February. This also puts them at higher risk for trafficking; the discovery of 31 children, some as young as 13, working to clean a Nebraska meatpacking plant in 2022 triggered a Department of Homeland Security investigation into whether some of those children had been forced to work to pay off trafficking debts.

Reporting by Jacob Bogage and María Luisa Paúl in the Washington Post implicates conservative lobby group Foundation for Government Accountability in a concerted national push to advance laws stripping child workers of protections. Experts at the Economic Policy Institute and elsewhere have been quick to point out that these state laws are in violation of federal law.

USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack sent a letter to 18 meatpacking companies in April, strongly encouraging them not to employ children in their facilities. “The use of illegal child labor — particularly requiring that children undertake dangerous tasks — is inexcusable, and companies must consider both their legal and moral responsibilities to ensure they and their suppliers, subcontractors, and vendors fully comply with child labor laws,” Vilsack said in the letter.

However, it’s not the USDA’s jurisdiction to police labor laws in food and agriculture, and it appears unlikely that federal enforcement will present any challenge to the shifting state laws. According to an article in Bloomberg Law, the Department of Labor “can educate the public about the law and use its extremely limited resources to focus its enforcement in states. But it can’t compel state labor officials … to enforce federal rules on their own.”

This is not the news child labor experts are likely to embrace with enthusiasm. “Of course, it’s good for kids to work when they reach an appropriate age but not in dangerous jobs like meatpacking plants and mills,” said Wurth. “And not in agricultural work that could lead them to be severely injured for life … What’s most damaging and cynical about these laws [is] instead of strengthening our labor laws and protecting workers rights, we’re putting kids at risk.”