Aiming to address a state labor shortage, a proposed bill would also let employers off the hook if child workers get injured.

“This is a sick, sick bill,” said Mark Lauritsen. “Any legislator in the state of Iowa that thinks this is an okay thing to do has got a real serious problem in their head about what’s really important in life.”

Lauritsen is international vice president at United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW), which in Iowa alone represents some 15,000 meatpackers at six large-scale plants owned by companies like Smithfield and Tyson. His strong words were directed at Iowa Senate File 167. Introduced in January by Republican state senator Jason Schultz and currently making its way through the legislature, it proposes to allow children as young as 14 to work in meatpacking plants, on meat-processing lines and at loading docks, for example.

If eventually signed into law by Republican governor Kim Reynolds, the bill would allow 14-year-olds to “apprentice” not just in meatpacking but also in industries like mining, construction, and demolition. For this to happen, the state’s department of workforce development would have to approve the “apprenticeship,” supervision would have to be available, and the work couldn’t interfere with a kid’s health, wellbeing, and schooling (although the bill doesn’t stipulate how those interferences would be determined). The legislation would also allow kids to work until 9 p.m. instead of 7 p.m. on school nights — as federal and Iowa law both currently stipulate — and drive themselves up to 50 miles with a special minor’s driver’s license.

The bill is “sloppily” worded, said Iowa Federation of Labor AFL-CIO president Charlie Wishman and is seemingly “in conflict with federal law ... If passed in its current form it’s going to leave a lot of confusion out there for consumers, for workers, for businesses.” The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 prohibits anyone under the age of 18 from working in hazardous environments and limits the weekly hours kids under the age of 16 can work.

According to Jen Sherer, senior state policy coordinator at the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), federal law still trumps state law for most private and all public companies. She also pointed out that the federal law allows children as young as 10 to work in agriculture, the most dangerous field of all. But she’d rather “end the two-tier system for youth work,” she said, than lower the standard for kids in other industries.

Most egregious with the Iowa bill, according to opponents: It would let employers off the hook in the event a kid got injured on the job, liable only in the event of “gross negligence” or “willful misconduct.” Reid Maki, director of the Child Labor Advocacy National Consumers League and coordinator of the Child Labor Coalition, calls this provision “very cynical” and the bill itself “probably the worst I’ve seen in 15 years because of its scope.”

Schultz and other backers claim it’s necessary to solve for labor shortages and, as a bonus, allows children to gain valuable work experience. “This bill is an incredible opportunity for everybody involved,” Schultz told The Gazette. “We’re going to end up with a generation of skilled leaders because of these efforts.”

“If you put kids in a dangerous situation, there will be injuries.”

If they make it to adulthood in one piece. According to Lauritsen, working in a packing plant is fraught with dangers, even off the kill floor. “I don’t care where you’re at … there’s fat on the floor, there’s blood,” Lauritsen said. Workers wear hardhats and layers of PPE such as non-skid boots; they also remove earrings, watches, or “anything that can get caught in the machines” and cause the loss of a finger, hand, or arm. (Amputations are common in the industry.) “If you put kids in a dangerous situation, there will be injuries,” Maki said.

Even lifting heavy boxes at the loading dock makes still-developing bodies prone to repetitive stress injuries. These injuries usually fall under the auspices of workman’s compensation, which Lauritsen said has been stripped over the years in Iowa to be “not nearly what it should be.” It’s unclear if injured child workers would be eligible even for what benefits remain.

Maki also takes issue with the extended hours the bill would allow kids to work — for under-16-year-olds, six hours a day and 28 hours a week during the school year, eight hours a day and 40 hours a week after Labor Day. “There’s going to be consequences to that,” he said, mentioning research that shows kids working over 20 hours a school week suffer lower grades and school completion rates, among other negative outcomes. He’s also concerned about exhausted kids driving home late at night.

The bill is the latest in an ongoing series of controversies in which Big Meat is implicated in threats to the health and safety of its workers, child or otherwise. This month, contractor Packers Sanitation Service was fined $1.5 million by the Department of Labor for employing at least 102 children as young as 13 during overnight shifts at meatpacking plants, some of whom sustained chemical burns.

“There’s this belief that you can hire a kid to work for minimum wage because they’re not trying to support a family.”

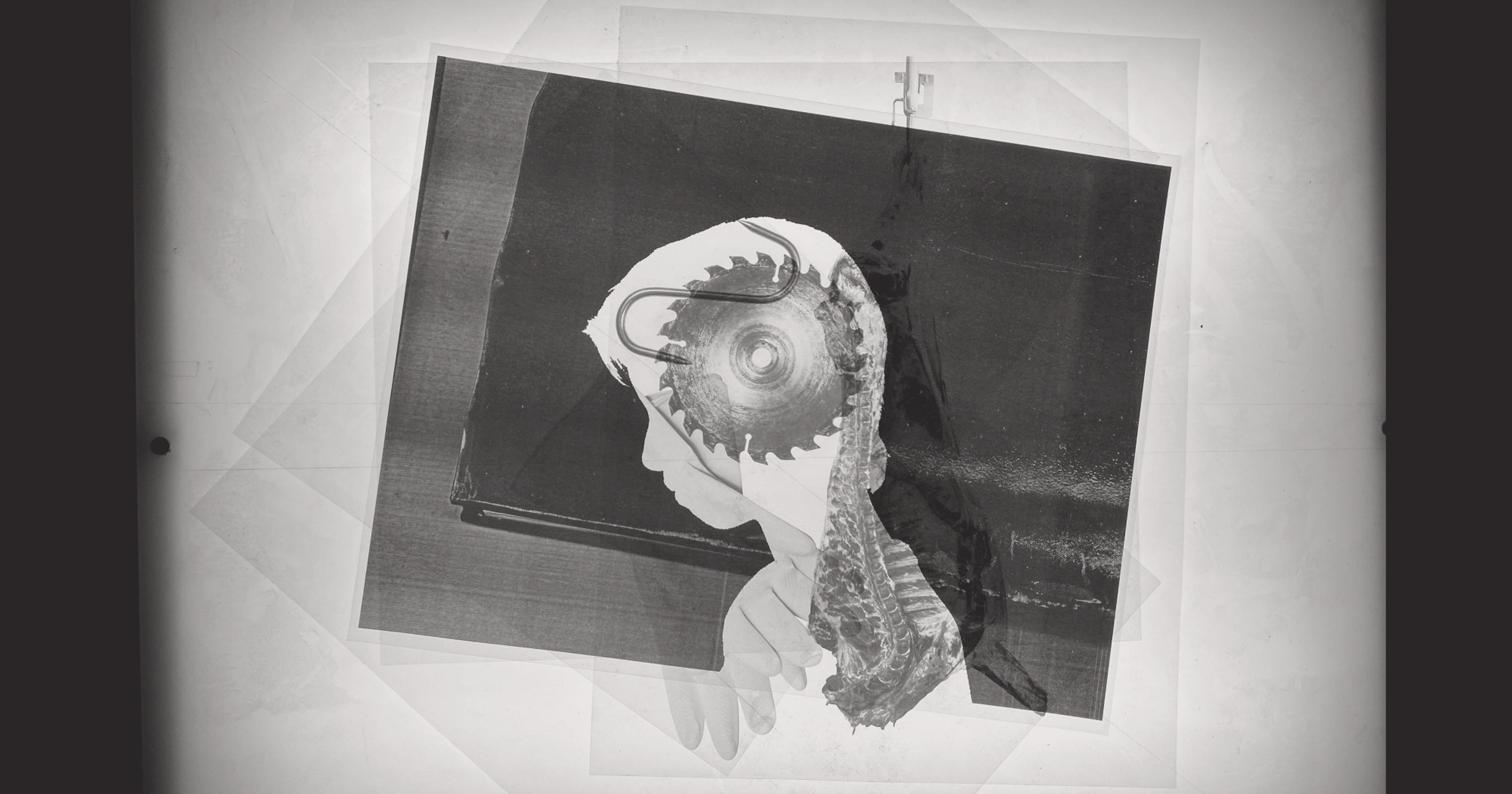

Tyson and JBS disavowed knowledge of these practices, but Wishman said the case highlighted the fact that the risks of child labor are “much, much more massive than anyone knows.” There’s also a history of it. A 2008 raid of a kosher meatpacking plant in Postville, Iowa, found 32 children working with power shears and circular saws. And it was an issue all the way back when Upton Sinclair wrote The Jungle, his seminal work on meat industry working conditions; some credit the book for helping usher in what labor protections we have now.

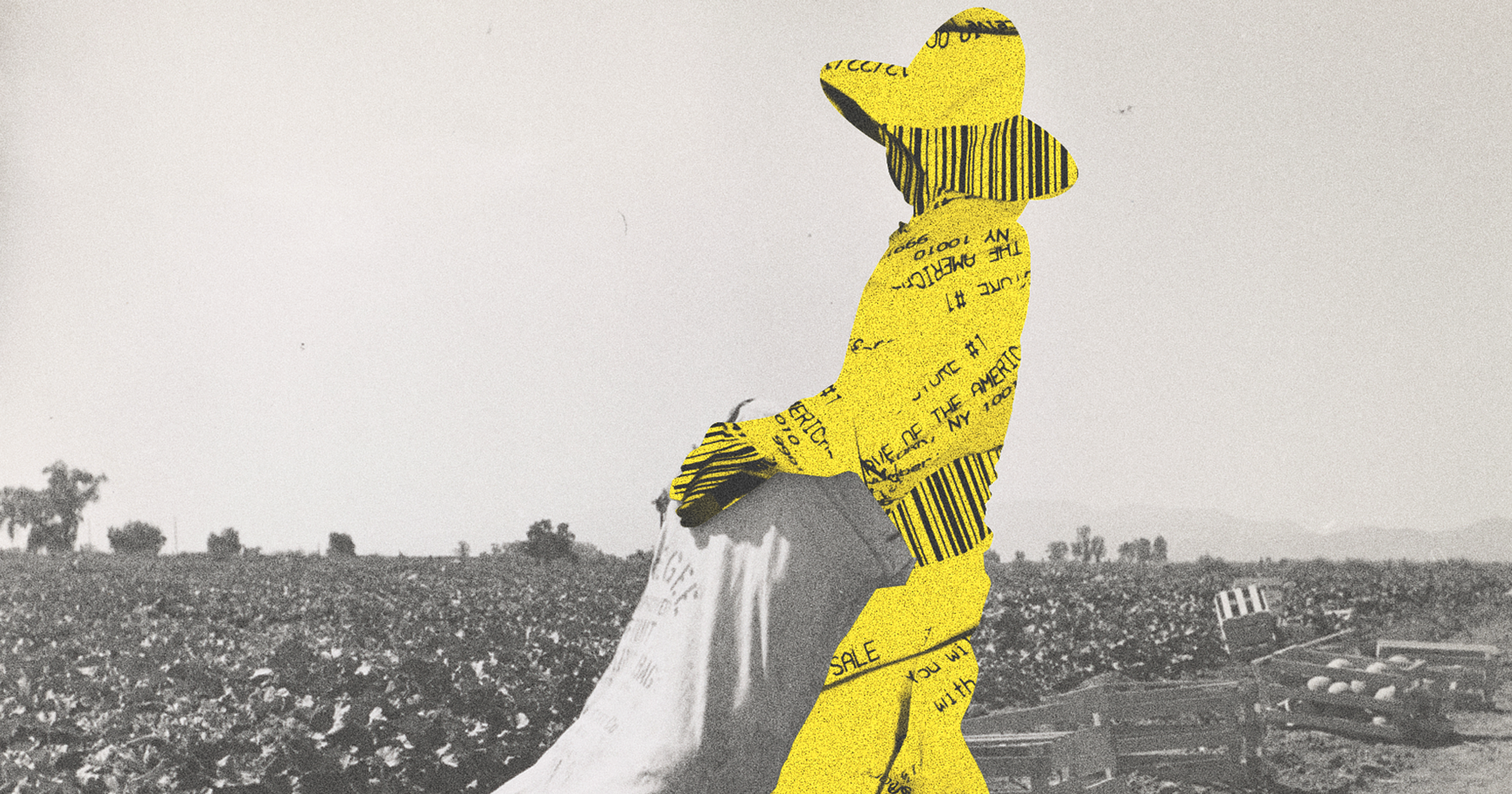

Most people in need of these sorts of jobs — and therefore most vulnerable — are Latino immigrant kids with “families who are very poor,” Maki said. “They’re at the bottom of the labor market, and their opportunities are somewhat limited, and they’re taking this job out of desperation.” He also has concerns about the potential for trafficking child laborers, a specter raised after the raid of four auto supplier plants in Alabama last year, where children as young as 12 were working.

Meat companies have also come under fire for failing to protect (adult) workers during Covid — refusing paid sick leave and proper in-plant safety strategies, as well as enlisting the Trump administration to help justify keeping plants open. Even before the pandemic, though, workers were notoriously exposed to dangerous working conditions, assaults, threats, wage theft, and more.

Would the big meat companies wade purposefully into a legally fraught employment landscape and expose themselves to more potential blowback? Tyson did not immediately respond to a request for comment. A Smithfield representative wrote tersely in an email, “We require employees at our processing facilities to be 18 or older,” in response to a query about whether child workers were necessary to overcome labor shortages.

“It’s the latest variation on the push that industry lobbyists have been making since the beginning of the Fair Labor Standards Act.”

“There’s an effort to look for cheaper labor” among meatpackers, said AFL-CIO’s Wishman, pointing out that Iowa minimum wage is $7.25 an hour versus the $21 per hour that starting adult union workers make in an Iowa packing plant. “There’s this belief that you can hire a kid to work for minimum wage because they’re not trying to support a family.”

EPI’s Sherer said that the Iowa bill, “shocking and extreme” as it is, fits a larger trend emerging in multiple states — eight by current count, including New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Minnesota — “to roll back child labor protections,” she said. “It’s the latest variation on the push that industry lobbyists have been making since the [beginning of the] Fair Labor Standards Act.” The Iowa senate bill was lobbied for by the state’s restaurant association, the Home Builders Association of Iowa, and the Iowa Association of Business and Industry. The restaurant association’s CEO told the Des Moines Register that the bill was necessary to update “outdated” jobs like shoe shining that the law currently allows kids to perform.

Lauritsen of UFCW said that even “high” wages often aren’t enough to retain workers at processing plants. “Meatpacking is physically hard work; $23 an hour with a little bit of overtime is enough to attract people … but I’ll leave that job for five bucks less an hour” if it’s easier, he said. “Kids is not the answer, that’s just stupid.” If the Iowa bill passes, he said the union “would have to strongly push to have contractual language that says nobody works in these plants under 18 years old.” (Although this would apply only to workers in unionized plants.) Failure to ban child workers at the bargaining table would mean the union would seek other actions. “Because we’re not going to have children work in our plants,” Lauritsen said.