After oysters are consumed, there are countless uses for their sturdy shells — including shoreline reparation. Why is it so hard for restaurants keep them out of the trash?

About a decade ago, Ryan Prewitt, executive chef and partner of New Orleans restaurant Peche, found himself in a pickle. The seafood restaurant was about a year old, and the raw oyster bar and menu of Gulf seafood was a hit. But Peche was limited on space, and between trash, recycling, composting, and glass, garbage was constantly accumulating everywhere. One might be surprised to learn that the worst element amid all of the chaos of a seafood restaurant were ragged oyster shells. They were heavy, wet, and they stank. Amid all of the other refuse, collecting between 5,000 to 8,000 shells a week with nowhere for them to go but the garbage can wasn’t working.

Prewitt thought the solution was a no-brainer: Staff could pack shells back into the cardboard boxes they were delivered in and return them to the supplier, who could then dump them right back into the Gulf of Mexico.

But he was very wrong. “We were told by members of the scientific community that [the oyster shells] could be infected with bacteria, and poison the water,” Prewitt said. By a twist of fate, at the same time Shell Oil was seeking to sponsor a trial oyster recycling program through the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana (CRCL) that year, and Peche was approved and enrolled in the pilot program for free. They’ve participated ever since.

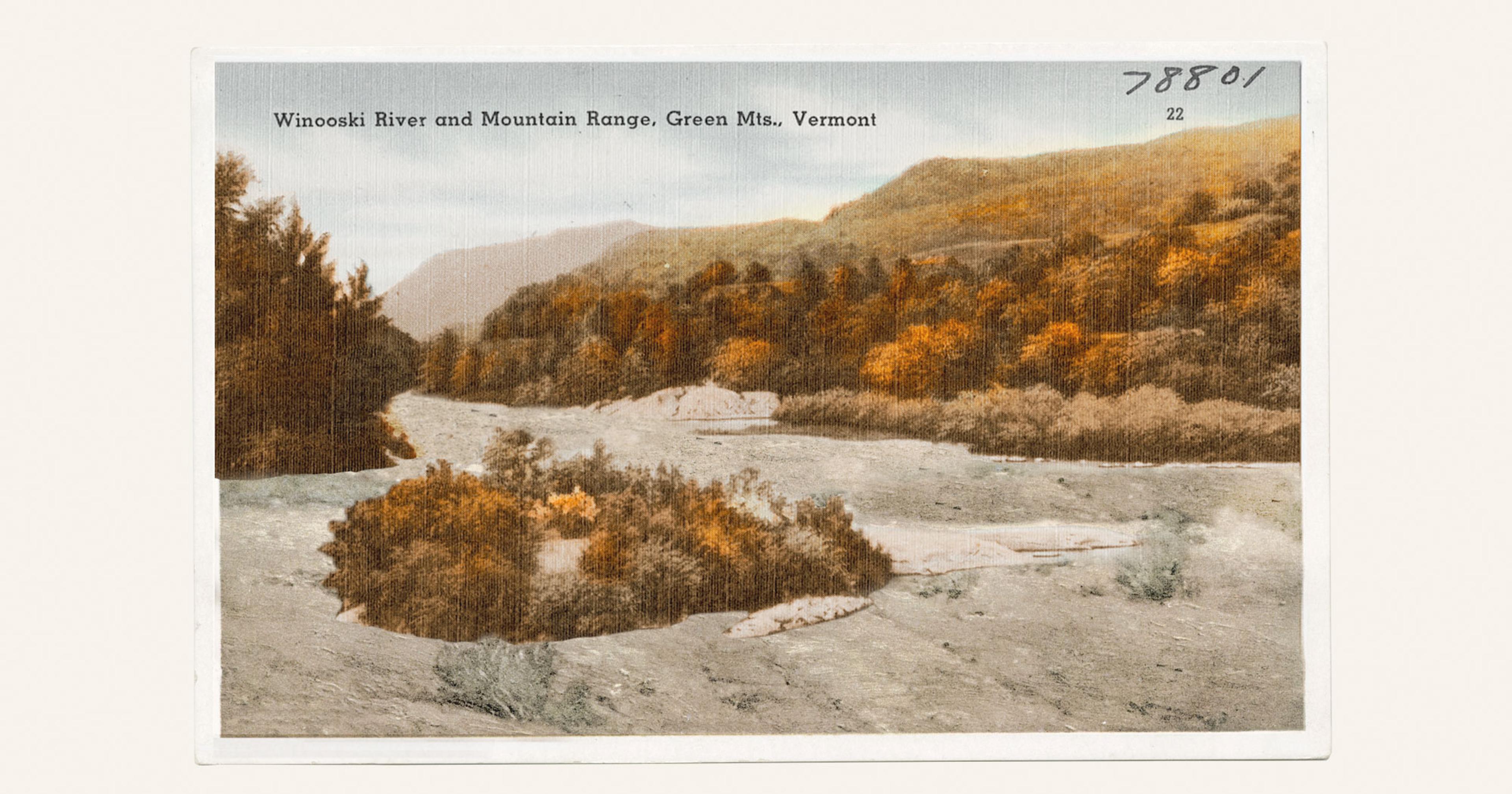

The aquaculture off of Louisiana’s coastline in the Gulf of Mexico has always been big business. Seventy percent of all oysters in the U.S. come from the Gulf Coast, and in 2018, Louisiana ranked third nationally for the highest seafood sales. The three main products that make up the bounty of state sales are farm-raised crawfish, catfish, and oysters, which alone generated $619 million in 2019.

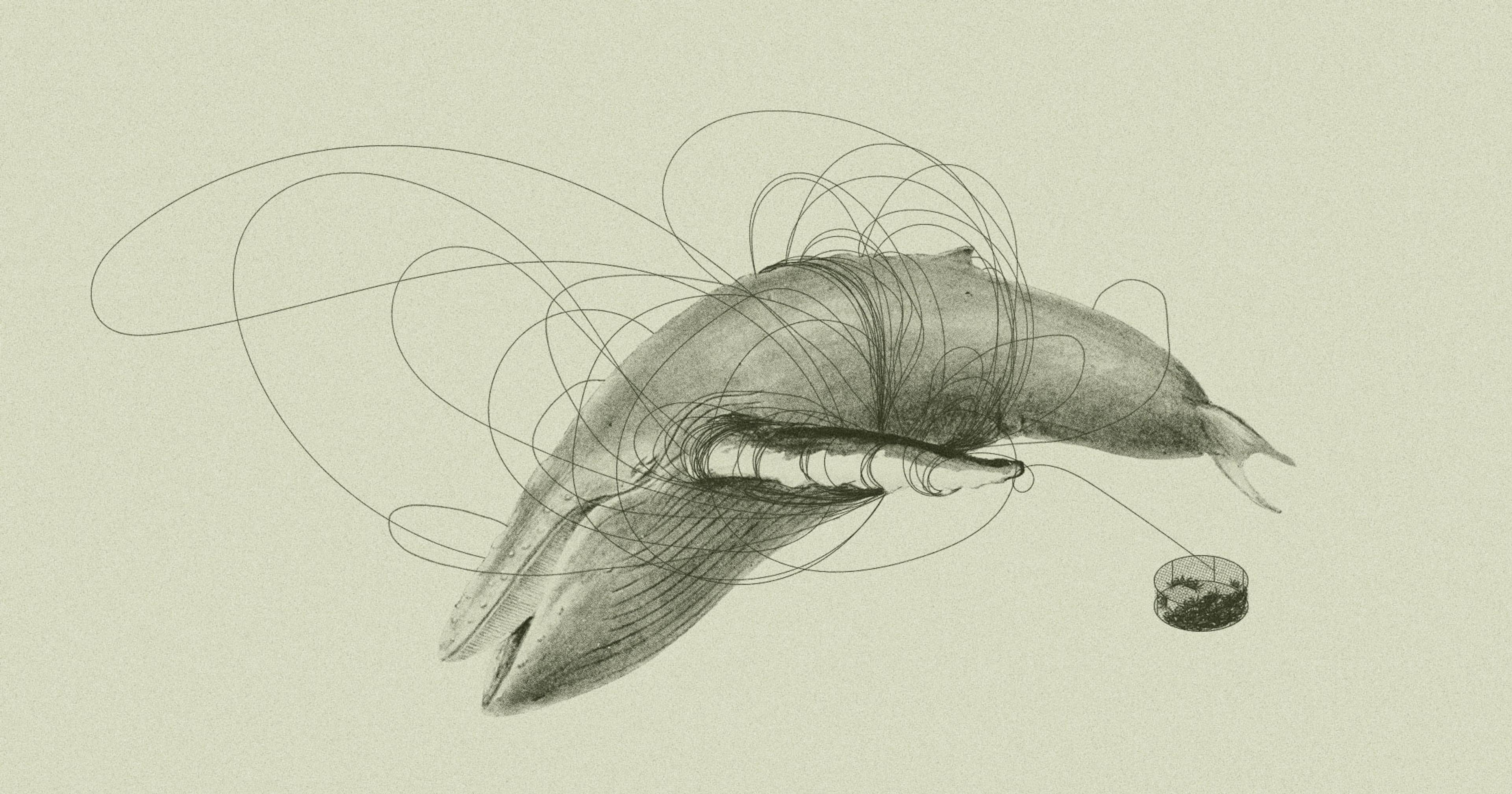

But a consistent, acute threat to the seafood industry is coastal erosion and wetland loss. To New Orleanians, it is no secret that the longevity of the city is correlated to the existence of the outer barrier wetlands that slow storms and their cascading waves.

How do you make sure every oyster shell gets recycled, and not thrown in the trash?

“Recent figures are [that we’re losing] a football field [of wetlands] every 100 minutes,” said James Karst, communications director for CRCL. “In less than a century, 2,000 square miles of wetlands [have] disappeared. They’re no longer wetlands, [but] open water that’s about the size of Delaware.“

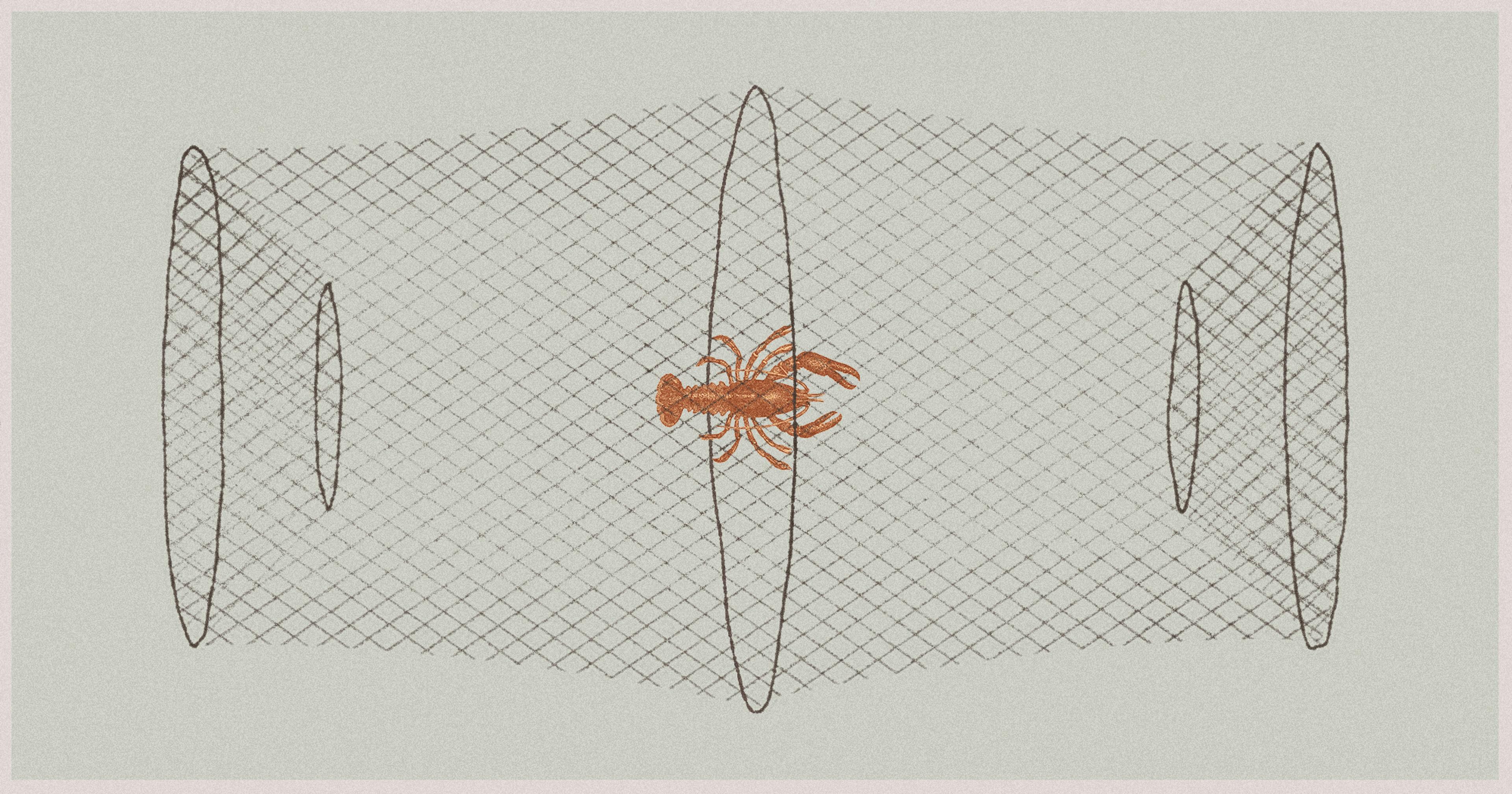

Thus, the Restaurant Recycling Program through CRCL that Peche started participating in came from multifaceted needs: If restaurants recycled their oyster shells and they were processed properly to prevent contamination, strategic oyster reefs could be installed to prevent land loss. Other benefits like water restoration and a greater oyster harvest for future generations are also invaluable. But a very simple, everyday occurrence can imperil this network of positive impact: How do you make sure every oyster shell gets recycled, and not thrown in the trash?

*

Oyster recycling programs are not a new phenomena. Maryland and Virginia operate collection services to restore the Chesapeake Bay, along with other regional programs in Mississippi, Galveston, and Tampa. But besides New Orleans, only one other city was truly defined by the oyster, yet tangibly lost it over a century ago.

“Pre-colonization, oysters were a huge resource for the Indigenous population,” said Charlotte Boesch, senior shell recycling program manager with the Billion Oyster Project (BOP) in New York City, an oyster recycling program that creates oyster reefs in the New York harbor via recycled shells from city restaurants. “During colonization and industrialization, [we] overharvested and dredged shipping channels, [which] destroyed the habitat and polluted our harbor. Oysters became functionally extinct, and [we] stopped having oysters in New York City.”

Though most have heard of iconic dishes like Oysters Rockefeller, it’s hard to really understand what was lost with the de-facto extinction of oysters by the 1930s. Early European travelers to New York reported that oyster shells were nearly 10 inches to a foot in length. Nowadays, oysters are considered large when they’re over 3.5 inches. Though bigger doesn’t always equal better, it goes to show that the waterway’s abundance has drastically changed.

“New York used to be known as Oyster City because they were shipped across the country, [but] all oyster harvesting shut down until the 1970s when the Clean Water Act passed,” said Boesch. Prior to the passage of the regulation, industry was free to dump waste and sewage into the city’s harbor, and oysters simply couldn’t survive. The Clean Water Act banned the dumping of waste into the city’s waterways, and the water slowly but surely became cleaner, and more hospitable to aquaculture.

Early European travelers to New York reported that oyster shells were nearly 10 inches to a foot in length. Nowadays, oysters are considered large when they’re over 3.5 inches.

The Billion Oyster Project launched in 2014 with a slightly different mission than the CRCL: In Louisiana, oyster shell installations in the outer wetlands were expressly to prevent land loss. For BOP, the larger goal is a cleaner coastline due to the filtration capacities of oysters. There is no short-term goal to eat the oysters of New York harbor because of the city’s sewage system design. With heavy rains, sewage still overflows into the surrounding waterbody, which is what budding oysters eat.

“If we had a billion oysters in the harbor, we would be able to filter it every three days,” said Boesch. From there, New Yorkers could finally, after over a century, safely utilize their central coastline for safe recreation, boating, and economic activity. Though the harbor is cleaner than it has been for the past 100 years, there is still a stigma that it’s dirty. With enough oysters and cleansing power, that could change, even if no one eats them at all. The problem is collecting what oyster shells are out there amidst the notoriously high turnover, limited space, and financial constraints of the restaurant industry.

“That’s our biggest challenge with the program,” said Prewitt of Peche. “We’re a fairly large restaurant with 100+ employees and people constantly coming and going … The system, on one hand, is established with a method for getting the shell into the bin, and it works, but to say it works all the time would just not be true.

”At Peche, a large dump bin to collect shells is situated next to the dish station with a top layer that allows for ice to melt and water to flow through. The detritus from the raw bar includes ice, lemons, and shell in one wet mix. That concoction is hauled periodically to this dump bin, where the ice melts off and spent lemons and shells are left. A runner will pluck all of the shells up and transport them to their own storage area periodically for weekly pick-up by CRCL contractors.

But all of this happens in a pressure-cooker where cooks, servers, managers, and hosts are trying to make and serve food, and if new hires aren’t educated about why and how to separate out all of the restaurant’s waste, shells can easily get routed into the trash, even with the most noble intentions from leadership. High turnover in restaurants is common in New York, too, which means that Boesch has to think about a metric of her success as not just as the number of restaurants that sign up for shell recycling, but how many stay engaged and participate year-round.

“There’s not enough oyster shell in the world or Louisiana that we could armour our entire coast with oyster reefs, so it’s a very targeted method of slowing land loss.”

To keep in touch with rotating chefs, Boesch produces a monthly newsletter for all participating restaurants to keep oyster recycling top-of-mind. The team also visits restaurants a few weeks after onboarding for a 10-minute preshift talk with servers and hosts so that they can explain the program to diners. BOP has also dipped their toes into conducting restaurant staff briefings with the front and back of the house in Spanish to help the message resonate with bilingual restaurant workers.

“Staff turnover and staff engagement is incredibly challenging, and the only solution is a very dedicated chef that communicates it to new staff,” said Boesch.

But the tiny act of dropping a shell into a bin makes a difference. Since 2014, CRCL has constructed 8,000 linear feet of shoreline with over 15 million pounds of recycled shells from participating New Orleans and Baton Rouge restaurants. Five barrier reefs have been constructed in the wetlands, including a project that helped stabilize ancestral mounds for the Pointe-au-Chien Indian Tribe. In 2023, Governor John Bel Edwards signed bill HB255 into law, a tax credit of $1 for every 50 pounds of oyster shell recycled by restaurants. New York has a similar bill in assembly right now.

“There’s not enough oyster shell in the world or Louisiana that we could armour our entire coast with oyster reefs, so it’s a very targeted method of slowing land loss,” said Karst.

By way of running Peche and working with local seafood purveyors, Prewitt has traveled all across the country to meet fishing communities and learn how to make these human and ecological ecosystems more sustainable for generations to come. He said that right now, much is difficult in the Gulf aquaculture industry. The work is hard, and many young people don’t want to do it. Buying a fishing boat is expensive, and there aren’t enough pathways for fishermen to access low-cost loans and grants to launch their business. Yet even for land loss and struggles with storms that impact oysters harvests, Prewitt is optimistic about the future of oysters and how far Louisiana’s management of the crop has come in the past decade.

“Offshore oyster versus offshore fin fishing is a considerably cheaper way to get into the fishery business. The start-up costs are lower, and the effort is frankly lower … The permitting is straightforward, and the system is set up for them to exist,” he said. “That’s a tremendous help to get more people into that industry.”