As the Southwest grows more arid, ranchers are using tech to sustain the economic and ecological viability of cattle — and protect the fragile living soil beneath their hooves.

“Cattle grazing at its soul is human impact,” said Kristen Redd as the sun set over southern Utah’s famous red rock cliffs. “It’s not about cows, it’s about how humans are controlling those cows.”

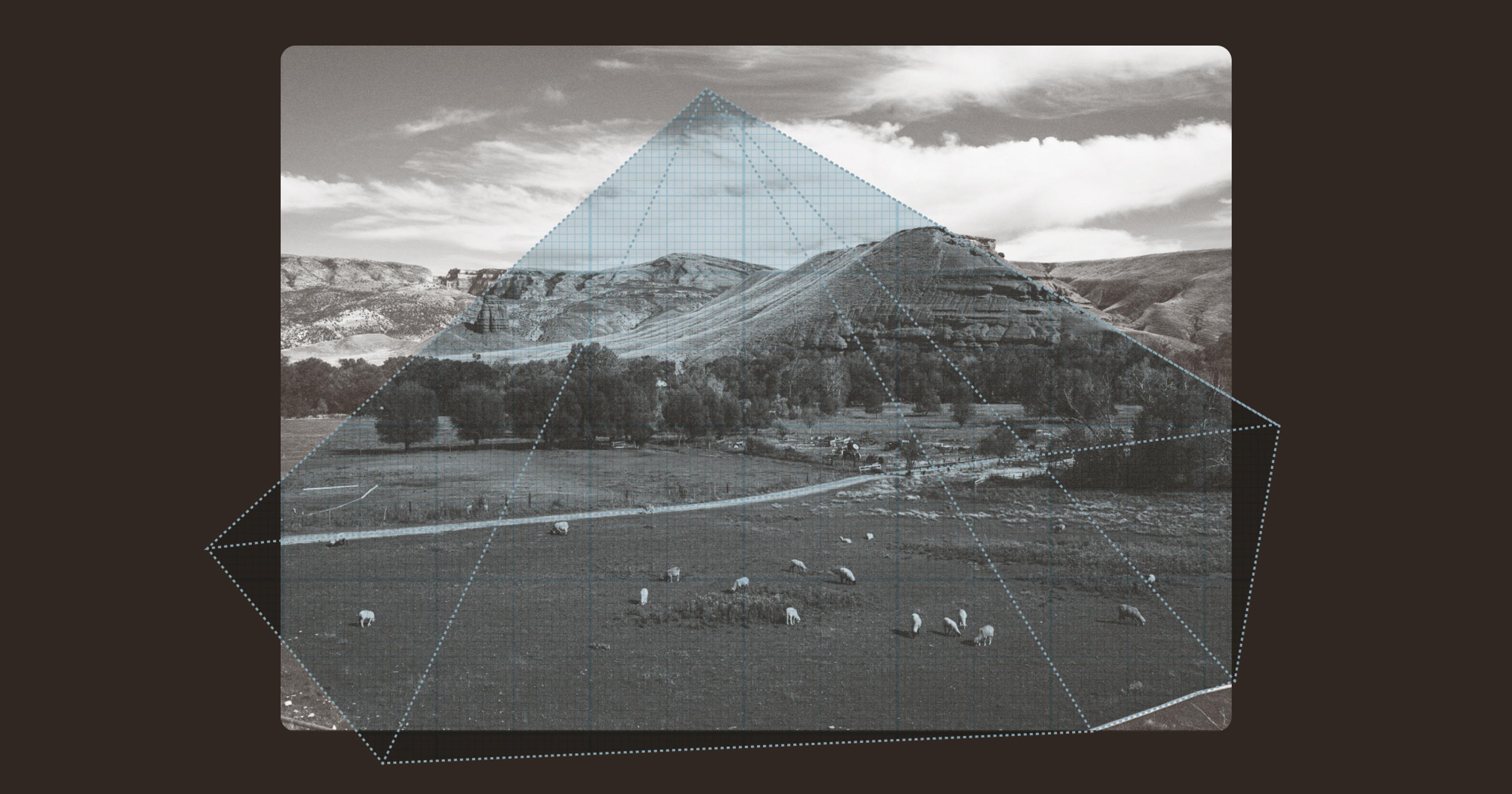

Redd resides at the Dugout Ranch, a vast 340,000 acres of rugged rangeland near the southern portion of Canyonlands National Park. The former childhood home of her husband, Matt, the couple have been ranching the property for decades. Now part of The Nature Conservancy’s Canyonlands Research Center, Dugout often acts as a hub for agricultural and scientific research of all kinds centered in the Utah desert.

It’s also one of five ranches selected by the USDA to test out precision ranching technologies — a combination of tools and heritage breeds — on its cattle practices. The Redds and a team of researchers monitor their herds through virtual fencing collars, GPS trackers, pedometers, and trough and moisture sensors, collecting data that could aid an ecologically and economically sustainable future of ranching in the arid Southwest. The Redds say they are most excited about the potential for virtual fencing, a system of customizable digital boundaries that send signals to livestock collars, keeping cattle in designated areas.

Ranchers have run their cattle through southern Utah’s red desert for nearly two centuries, taking advantage of the region’s expansive terrain and abundant native grasses. The landscape sprouts towering cliffs and sandstone arches, but less visible are the essential soil components that make the foundations of this desert ecosystem. “We have biocrust growing on our rangelands and it’s in our best interest not to overly impact it,” Kristen said.

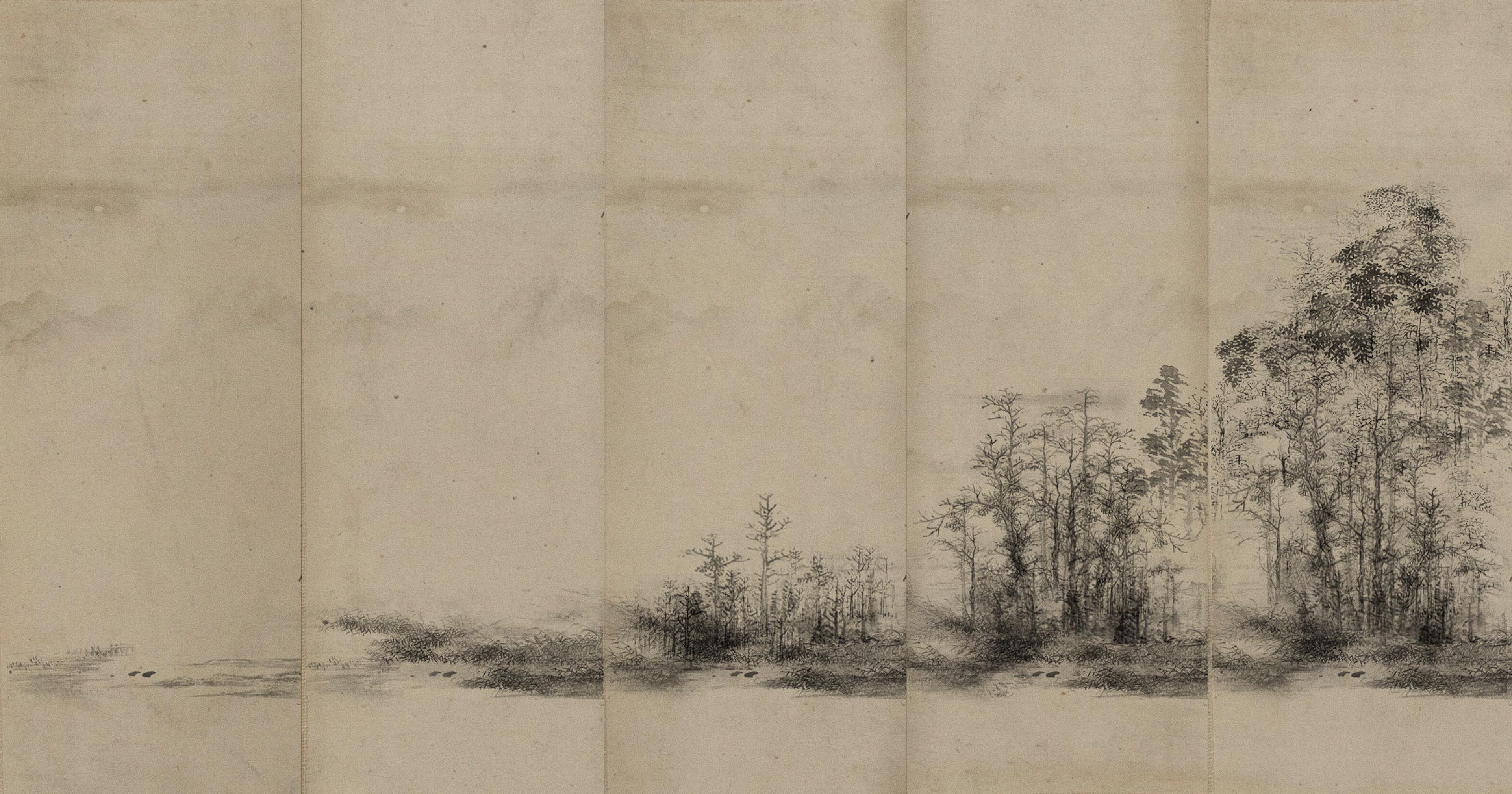

Biocrusts, or biological soil crusts, are collections of cyanobacteria, lichens, mosses, and other organisms that cover the fine, sandy soils of the Colorado Plateau. Collectively, they form layers — crusts — across the desert floor harboring much needed nutrients and moisture for desert plants. Biocrusts essentially hold these desert ecosystems together, preventing erosion and dust. Without them, the landscape would be covered in sandy dunes, and rangeland cattle grazing would be impossible.

But evidence suggests biocrusts are being increasingly disturbed by upticks in human activity — ranching, oil and gas, and outdoor recreation are all culprits. “Biocrusts are very strong horizontally because they hold the soil together. But they have almost no resistance to being stepped on or trampled in any way,” said Kristina Young, a soil scientist and founder of Science Moab in Moab, Utah. The resulting dust from crushed biocrust blows across the region, accumulating in undesirable places. “When dust lands on the Rockies it changes the snowpack,” Young said. “Studies show snow is melting 30 days faster because of dust on snow, which has huge implications for the Colorado Plateau.”

Dust isn’t the only repercussion of disintegrating biocrusts; their disappearance could endanger highly effective carbon sinks present in deserts with abundant grasses and shrubs — like the Colorado Plateau. Less biocrust means more erosion, preventing desert plants from growing and absorbing carbon dioxide. “Biocrusts stabilize the soil in a big way, and plants and seeds need stable soil to grow, and need protection from erosion,” Young said. They retain much-needed water and exude natural carbon and nitrogen into the soil, creating a fertile environment for plants to thrive.

A spotted Raramuri Criollo cow stands among the Dugout Ranch's herd of Red Angus and hybrid Angus-Criollo cattle.

Soil scientists are also studying the role of biocrust itself in the carbon cycle, determining whether its colonies sequester carbon dioxide at the same rates as shrubs and grasses. Considering biocrusts cover an estimated 12 percent of the planet’s landmass (twice the amount as tropical rainforests), losing them could have massive effects on the future of carbon reduction. On top of physical disturbances, climate change and hotter weather are hindering biocrusts’ ability to recover from damage. “Not disrupting it is essential to not disrupting these ecosystems,” Young said. “These intact dry places have a lot of a value.”

One of Dugout’s major goals in testing virtual fencing is to monitor the protection and regeneration of biocrusts on the range. “There’s the benefit of being able to control livestock without a physical structure … or potential for someone to leave the gate open,” Matt Redd said. “It really opens up the options of how you can control livestock and coordinate that with [restoration] goals.”

Virtual fence boundaries can be drawn in an online dashboard in any shape and size, allowing for flexibility when protecting sensitive areas is a priority. The solar-powered collars train livestock by emitting a loud tone followed by a shock when an animal approaches an invisible boundary. Kristen Redd said it takes less than a week to train cattle to heed the tone so they won’t receive a shock, but “there are always some cows that just aren’t with the program.” The collar will only emit three shocks to a disobedient cow. “Then you have to go find them,” she said.

The livestock themselves are also a piece of Dugout’s sustainability puzzle. Part of the precision ranching program includes monitoring a heritage breed of Raramuri Criollo cattle for their impact on desert lands. Originally brought to the Americas by the Spanish, Criollo became isolated among Indigenous Tarahumara communities and naturally evolved over the centuries to adapt to desert climates and foraging. Previous USDA experiments found that they travel farther from water than Angus — the beef of choice in the Southwest — are more active in the heat, and eat hearty shrubs as well as grasses.

Matt Redd checks the location of his cattle on the USDA precision ranching online dashboard.

“Across the Southwest with climate change we’re seeing … diminishment of native grasses and an increase in native woody species of brush,” Matt said. “So if you have an increase in brush and you have an animal that can do well on it, that’s important.” Because Criollo are about 400 pounds lighter than Angus, the Redds are breeding Criollo-Angus hybrids that can potentially have less damaging effects on biocrust and still provide an economically viable product. “If you graze the right breed at the right time and right place, ranchers can save on inputs — save on feed and vet bills,” said Sheri Spiegal, a rangeland management specialist with the USDA.

While virtual fencing isn’t necessarily a new technology, it hasn’t been available for ranches in the West until recently, mostly due to the vast remote territory many rangelands encompass. Reliable data connections remain a persistent issue in our less populated rural areas. “The biggest challenge in these huge ranches is getting the connectivity,” said Spiegal. “We’re trying different connectivity types like radio, white space, and cell data to connect the sensors to the dashboard.” The Redds tow portable towers on trailers when setting up virtual fencing in more remote pastures.

Once they are up and running, Matt sees the potential to not only protect biocrusts and sensitive areas, but also to run the range more efficiently. “Maybe you would spend, out of a year, three months gathering and moving cattle. With the tech that’s cut down to three weeks,” he said. “Because you know exactly where they are, you go to exactly where they are.”

But both Kristen and Matt acknowledge it’s not a perfect system. Real-time data distribution and storage is a concern for many people, ranchers included. Who owns the data collected by these collars and monitors? Should that data be public or private information when these tech programs are supported by the U.S. government? How hackable are the systems? These are questions the Redds and other participating ranches are still trying to figure out with the USDA and private companies that manufacture the technology. And while sensors and collars provide an abundance of information on cattle and rangeland conditions — such as rainfall, plant life, and trough water levels — there could be unintended consequences of moving away from working the range the old-fashioned way.

Black moss and yellow lichen grow along the soil on the Dugout Ranch as part of essential desert biocrust colonies.

“[The system] is giving you more information but it’s maybe not information you want to be solely dependent on. There’s nothing that replaces being out in the landscape,” Matt said. “Right now it’s more of a theoretical or esoteric concern, but over the course of the next several decades it could make our relationship with the landscape better but it could also make us more detached from it.”

Whether focusing on cattle breeds that are lighter on the land or technology that better controls them, the Redds said that each rangeland is going to need its own process to remain relevant in a rapidly changing environment. “I’m not a big believer in silver bullets. I think it’s going to be a lot of things making the difference,” Matt said. “I do see virtual fencing facilitating being a steward of the ecology for ranchers. And as we experience the impacts of climate change, changing land use … economic and ecological health, integrity, and sustainability are almost inseparable.”

Biocrust has been damaged by past overgrazing practices that have been long abandoned, but the scars can be seen in old corrals and trails. It can grow back with time, but the heavier the impact, the more difficult the recovery can be. “We’ve seen in the past when soils are compacted through grazing, through oil and gas and now we’re seeing that happen with [outdoor] rec,” Kristen said. “We can point at cows or oil and gas as being the bad thing, and if we get rid of those things it will solve all of our problems, but it won’t. It’s us. It is us that is the impact on this landscape.”

And while virtual fencing tech is just beginning to take hold, Kristen daydreams that ranching’s human impact could possibly be mitigated because of it. “Maybe we could get rid of all these fences in the West. Which is a nice idea, but we’re not there yet,” she said. “The West without fences would be magical.”