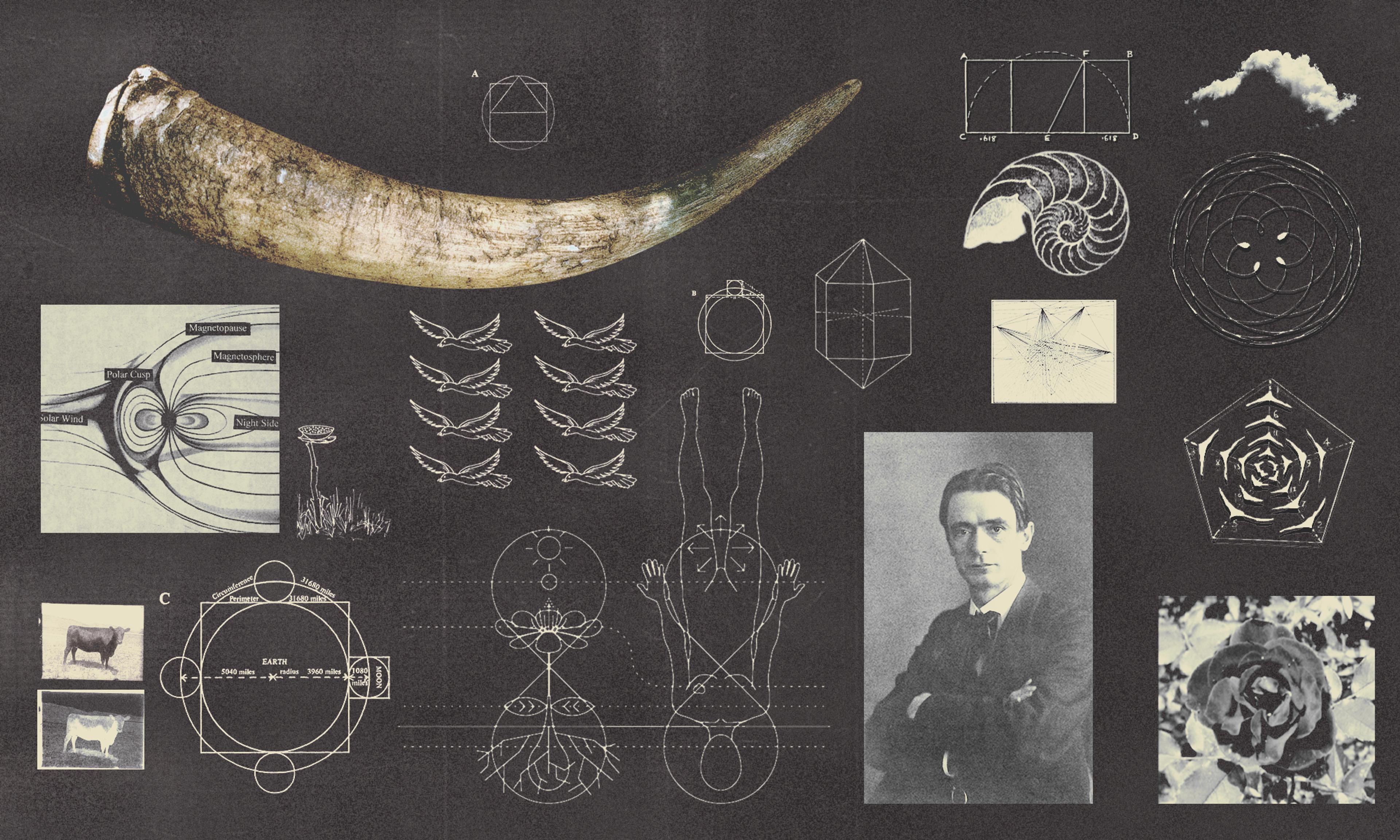

Its practitioners describe the 100-year-old approach as “organic-plus,” but its central rituals are more witchy than scientific.

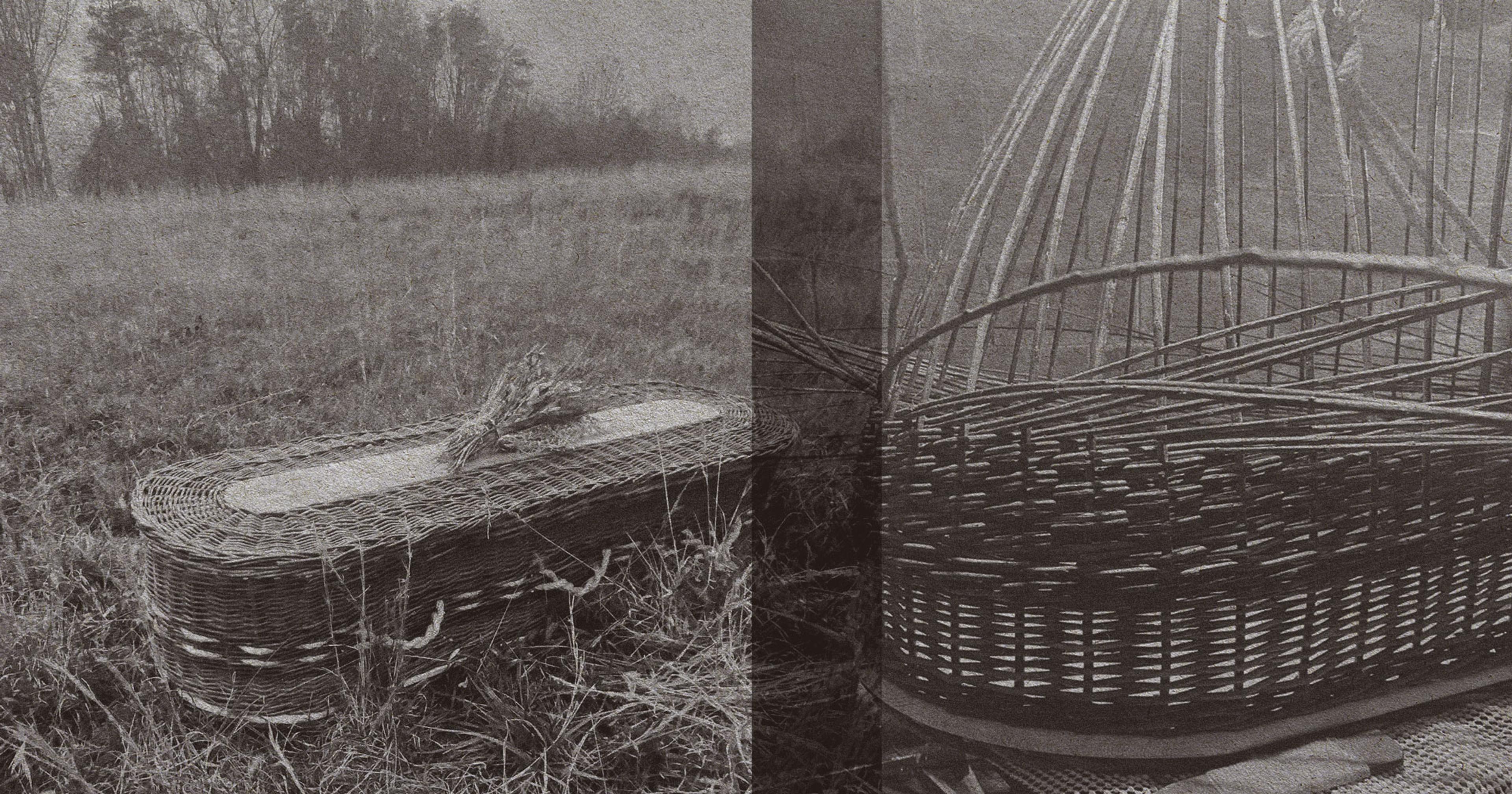

On a biodynamic farm, fall means it’s time to make some Preparation 500. A lactating cow’s manure is packed tightly into a horn and buried in the ground, with the opening facing downward to facilitate drainage. The farmer will have to wait until the following April to unearth the horn and its contents, which should smell pleasantly of forest soil. Stirred with water for exactly one hour, alternating clockwise and counterclockwise stirs, the hornmanure will then be sprayed over the fields, ideally at dusk, under an overcast sky.

Proponents of biodynamic agriculture, which celebrates its hundredth anniversary this year, are not unaware of how their practices can seem to outsiders. Reactions, one Oregon biodynamic farmer wrote, can range from intrigue to “hogwash.” Although based on the work of the Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner, it emerged in tandem with the organic movement; these days you often hear it described as “organic-plus.” Practitioners emphasize concepts with broad appeal, like the idea of a self-sufficient “farm organism,” and tend to refrain from mentioning the magical thinking at the movement’s heart. But after a closer look, biodynamic farming’s esoteric practices are as prominent as ever.

Roughly 10 years after an intriguing but brief volunteering stint on a biodynamic farm, I embarked on a day trip to Hawthorne Valley, a biodynamic dairy and vegetable operation sprawling over the upland hills where New York’s Hudson Valley gives way to the Berkshires. During my visit Steiner’s name came up again and again. There are other “guiding lights,” but “Steiner is at the base of everything that we do,” said Spencer Fenniman, Hawthorne Valley’s farming director.

If the name sounds familiar, that’s because Steiner is also the guiding light behind Waldorf schools — pricey institutions best known for their handicrafts, strict screen-free policies, and occasional antivax-driven measles outbreaks. Chosen for its proximity to a highway and train station, Hawthorne Valley started as a demonstration farm where Waldorf students could come for field trips. It wasn’t until the mid-1970s that production really kicked off. “They had 300 acres,” Fenniman said, and realized they needed a certain amount of livestock to manage it. Today the organization also runs its own school and a sizable natural foods store, which has expanded considerably over the past couple of decades.

Fifty years later, Hawthorne Valley remains a destination for New York City’s Waldorf students. Zahra Booth was one of those students, visiting on elementary school field trips, attending summer camp, and volunteering as a middle schooler. She’s now spent a few years working on small-scale and biodynamic farms. Every farm has some kind of underlying philosophy, she told me, but biodynamics is unique. “There’s definitely a certain magical thinking that goes into it, which either you’re on board with or you’re not.” I was also drawn to biodynamic farms as a teenager — in my case, for their ecological commitments and plain beauty — but, until recently, I hadn’t really learned the full story.

Born in 1861, Rudolf Steiner spent nearly a quarter century on the lecture circuit, where he held forth on topics as varied as mysticism, medicine, the arts, and race: He taught, among much else, that the souls of Black people were suspended in perpetual childhood and the souls of Asians in perpetual adolescence. (The U.S.-based Council of Anthroposophical Organizations continues to recognize Steiner’s “profound insights” while rejecting his racist statements.) Near the end of his life, in 1924, he turned his attention to agriculture in response to a group of farmers, concerned about the perceived deterioration of their crops. He used his well-honed method of “spiritual research” to outline the preparations, which continue to be the central factor distinguishing biodynamic from organic agriculture.

Like hornmanure, “horn silica,” which consists of ground-up quartz, is buried in a cow horn and sprayed over fields in minute quantities. The idea is that the substances act as a kind of homeopathic medicine, attracting “new life forces from the cosmos.” Another six preparations are made from different plant materials buried in animal “sheaths” (stag bladder, cow intestine, etc.) and distributed across the compost pile in order to infuse it with a “cosmic intelligence.” If you’re confused, don’t worry: “Biodynamics,” wrote the respected practitioner Hugh J. Courtney, “cannot be grasped by intellects that are conditioned by an education that currently is so focused on the material world.”

“It’s been stigmatized as hocus-pocus.” But rituals also offer people access to “mystery and magic” in a way that technology can’t.

That said, biodynamic farmers don’t hesitate to allude to scientific evidence that supports the preparations’ efficacy — much of which is contested. The Swiss “DOK” trials have produced 46 years of data comparing biodynamic, organic, and conventional methods, some of which reflect positively on biodynamics. Martin Hartmann, senior scientist in the Swiss university ETH Zurich’s Sustainable Agroecoystems group, conducted his doctoral research on the trials. But even he recognizes their limitations. The DOK trials’ biodynamic plots receive composted manure, while organic plots receive partially rotted manure; as a result, it’s impossible to isolate the preparations’ effects.

Research analyzing the preparations in more controlled settings has so far failed to consistently demonstrate either their benefits or mechanism of action. Although fermenting manure in a cow horn of course produces microbes, it’s hard for Hartmann to see how they could outcompete with the soil’s existing microbial communities when administered in such miniscule quantities. “I personally would be very surprised if these preparations would do anything,” he said.

In his work with biodynamic farmers, though, he noticed one distinguishing factor: They were unusually passionate about their work. “They observe their fields very carefully,” he said, and try new things in response to varying environmental conditions. “Biodynamic farming could show better soil health,” he said, “just because these farmers care a lot more about this.”

“I can absolutely understand a scientist calling it a pseudoscience,” said Anna Pigott, a Swansea University geographer who conducted research at a biodynamic CSA in South Wales. But for the farmers she talked to, Pigott said, it seemed to be “kind of irrelevant whether or not biodynamics appeared to work in a scientifically proven sense.” While the farmers did attribute an anecdotal effectiveness to biodynamic rituals, just as important was how the rituals could reconfigure human relationships to soil and other “more-than-human” entities.

“You’re producing food, which is the most important thing that you can do” — and a belief structure “adds a sense of purpose and seriousness to the work.”

“It’s been stigmatized as hocus-pocus,” Pigott said. But, she said, rituals also offer people access to “mystery and magic” in a way that technology can’t — and encourage a valuable reverence toward nonhumans.

“I would be lying if I said I could tell the stars have an impact on the vegetables,” admitted Spencer Fenniman of Hawthorne Valley. But he cited other benefits to the practice of biodynamics: it “opens us up to a certain type of thinking which can lead to a lot of freedom of possibility.” From that internal development, he claimed, you can improve not only soil but also broader communities.

***

Not every biodynamic farm is as sprawling as Hawthorne Valley’s, but even smaller operations emphasize their community affiliations. Central to Steiner’s philosophy, Fenniman said, is the idea that “agriculture is connected very much to every part of life.” One of the first things a new biodynamic farm does, he said, is work to create community.

Hawthorne Valley is far from the only Steiner-centered complex in the region. The Threefold “living community of practical work” in Rockland County, New York, includes two Waldorf schools, including one focused on special education, as well as a biodynamic CSA, a medical center, a senior living community, and a host of educational courses on anthroposophical speaking, dancing, and teaching. Closer by, several Camphill villages — commune-adjacent institutions based on Steiner’s philosophies — are home to disabled and non-disabled people who live and work alongside each other, often at on-site biodynamic farms. Further south, Kimberton, Pennsylvania, hosts a similar array of Waldorf schools, biodynamic farms, and Camphills. Zahra Booth called these places “fortified.”

I didn’t attend Waldorf school, although I was jealous of a neighborhood pair of siblings who did. Having temporarily relocated to my New England hometown to care for aging grandparents, by middle school my friends had returned to a Camphill in Kimberton, where I was introduced to both Steiner and to biodynamic farming over years of semi-regular visits. Their family shared a roomy pink house on a hilltop with several developmentally disabled adults and a rotating cast of international volunteers; other houses were nestled beside hayfields, orchards, and herb gardens. I still miss the interminable afternoons I spent sprawled out beside the quiet, hot asphalt of the community’s roads, watching residents trek to their work sites and home for lunch.

“I would be lying if I said I could tell the stars have an impact on the vegetables. But it opens us up to a certain type of thinking which can lead to a lot of freedom of possibility.”

One summer I signed up to work at the CSA and dairy. As at all biodynamic farms, the milking cows still had their horns — Steiner believed they were integral to the digestive process —which meant that they also regularly speared each other in the vulva. I’d watch farmers apply homeopathic calendula ointment to the cows’ gynecological wounds and wonder if the horns were really worth keeping. Still, every morning I looked forward to drinking the cold, fatty raw milk they produced. My friends had welcomed me into their world, and I loved it too much to worry about the dangers of bacteria.

There is a younger generation that’s interested in biodynamics, Booth said — biodynamic wine is increasingly popular — but it’s the older generation that tends to be more dogmatic about it. Booth doesn’t consider herself a “hardcore believer,” but when working on organic farms, she sometimes feels like something is missing. There’s already a magical aspect to farming, she said — “you’re producing food, which is the most important thing that you can do” — and a belief structure “adds a sense of purpose and seriousness to the work.” That has some kind of effect, she believes, whether from the hornmanure spray or from the accumulated intention of farmers walking through the fields, step by step, reflecting on the land and the seasons.

But biodynamics can also make that work more difficult, especially for farmers following the planting calendar, which tracks celestial influences on different parts of the plant — root, leaf, flower, fruit. Booth gave an example: “If you need to plant carrots one day, and it’s a leaf day, then you can’t.”

Recently, Anna Pigott learned that one of the farms she studied is no longer using biodynamic practices — not because the farmer doesn’t agree with them, but because “he just found it a real time drain.” For greatest effect, the preparations should be administered not only during certain times of the year but under certain weather conditions.

Scheduling, Pigott said, had become difficult. “Sometimes,” the farmer told her, “I just want to go surfing with my son.”