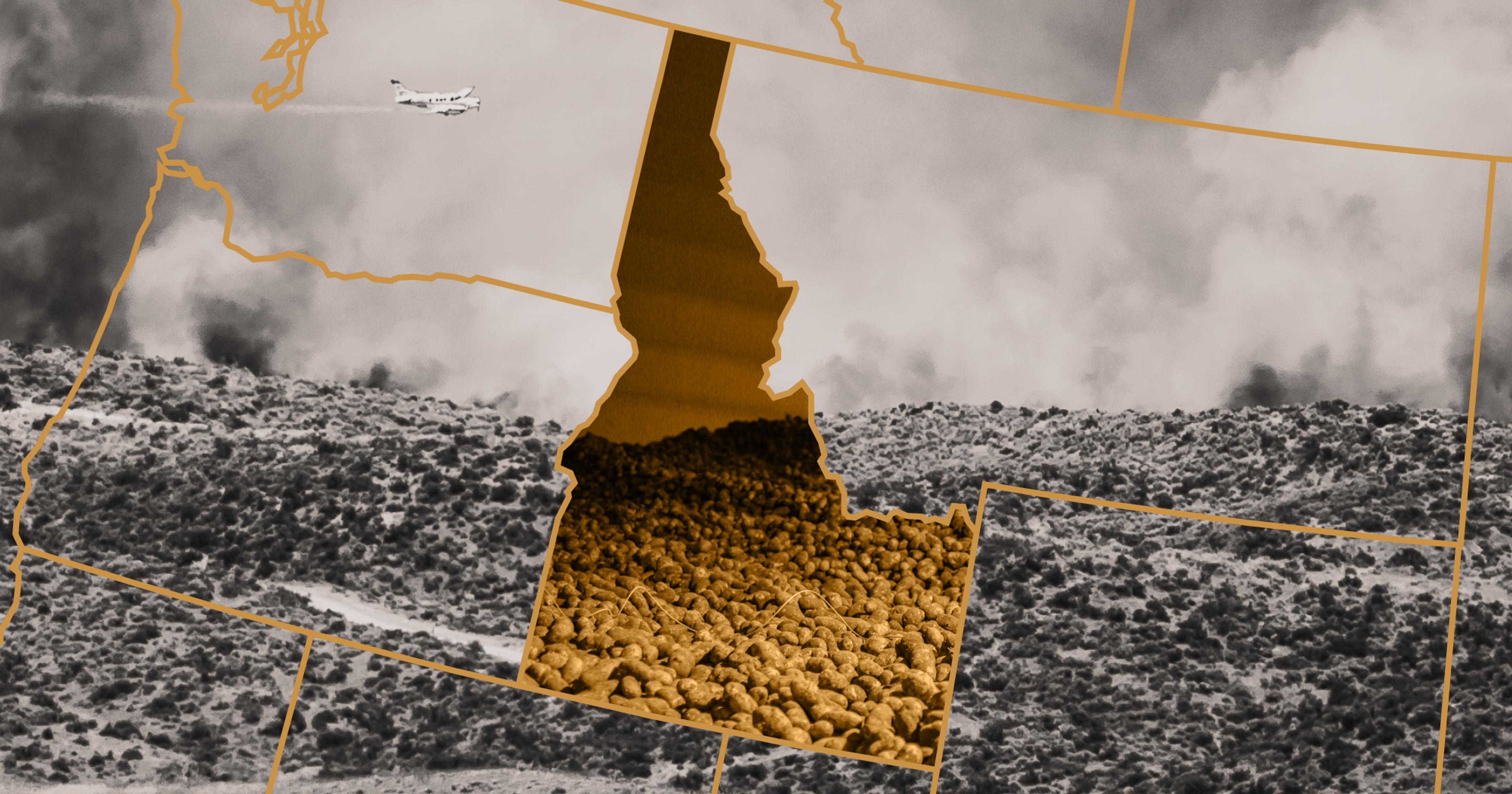

And what Idaho researchers are doing to prepare the state’s top crop for a smokier future.

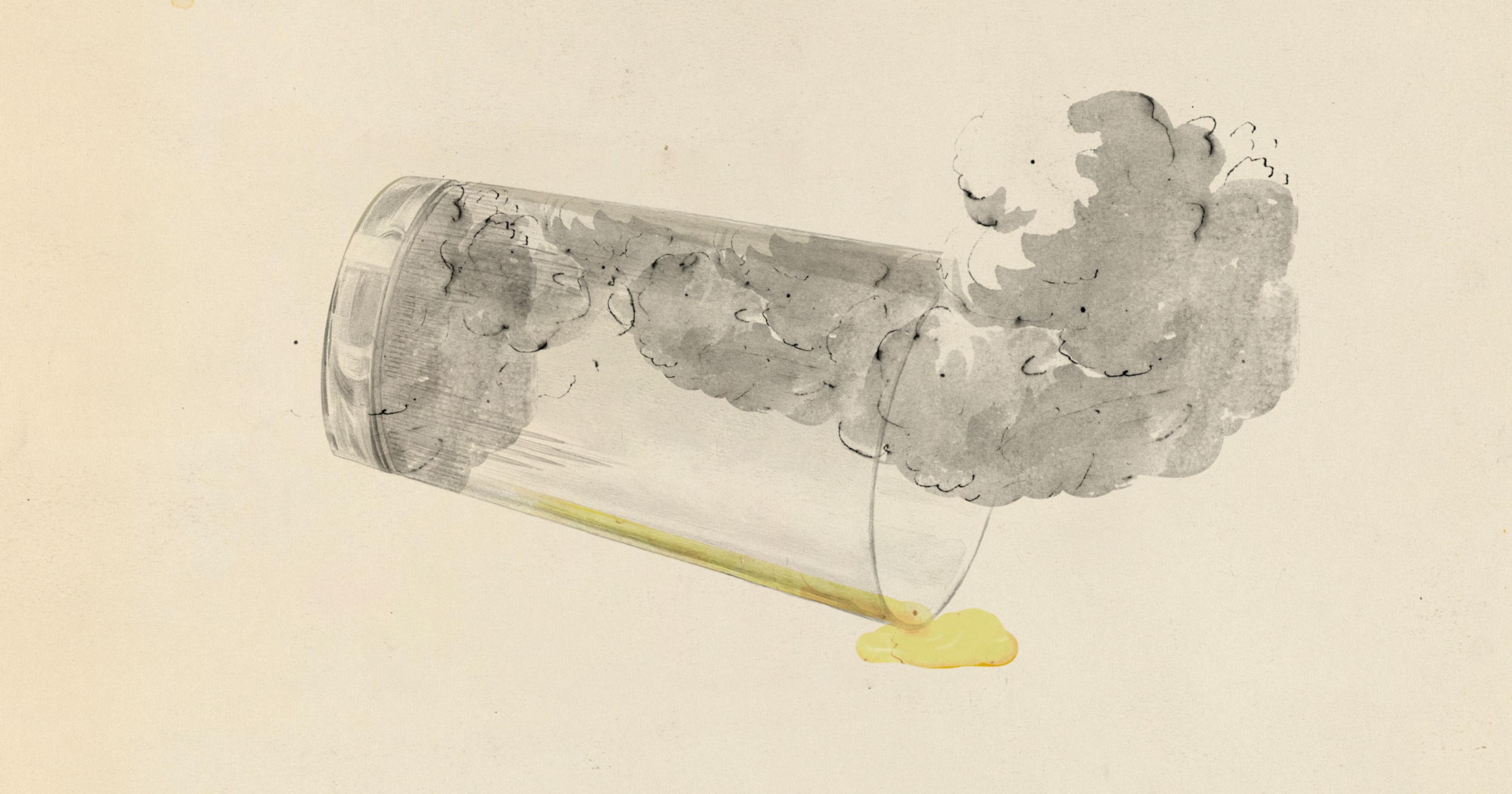

Wildfires in the West are growing larger and more frequent, making smoke exposure an increasing threat to farmworkers, as well as a number of different crops. In recent years, smoke pollution has impacted the quality of wine grapes in states like California, Oregon, and Washington, and has factored into reduced milk production in dairy cows. How harmful it is to other crops, however, is still unclear.

Similar to how it affects humans, smoke can block out sunlight and inhibit photosynthesis, causing plants to have trouble breathing. When it comes to wildfire smoke in Idaho, the primary crop concern is, of course, potatoes. The state leads the nation in production, growing more than one-third of all U.S. potatoes, and is responsible for processing the vast majority of the country’s frozen and dehydrated potato products. Idaho potato growers brought in a record $1.3 billion last year — a significant contribution to the state’s economy.

As wildfires in Idaho and its neighboring states increase, so do threats to the state’s top crop.

“We’ve had, probably seven out of the last 10 years, some pretty extensive periods where we’ve had pretty heavy concentration of wildfire smoke over our potato growing regions in southern Idaho,” said Mike Thornton, professor of plant sciences at the University of Idaho. “Growers had noticed that in some of those years, their yields were down and the potatoes did not store as well.” After an intensely hot summer last year, potato farmer Doug Gross told the Globe and Mail that he estimated his yields were down 10-15%.

In an effort to get a better grasp on the problem — and offer possible solutions — Thornton has teamed up with Boise State University chemistry professor Owen McDougal to determine exactly how wildfire smoke affects certain potato varieties. The researchers are studying how smoke changes characteristics such as taste, size, yield, and storage potential.

The deep, seemingly unaffected by smoke, roots for the project were first planted in 2012, when Addie Waxman, now an agronomy manager for the world’s largest potato manufacturer, McCain Foods, was walking through hazy potato fields in Washington. “There was so much smoke, it was just unbelievable,” she said. “That’s when I noticed that some potato plants just kept living, and others appeared to suffer under the canopy of smoke.” In addition to what Waxman observed about varietal difference in the field, she also heard anecdotal reports that potato stocks in cold storage centers were far more prone to disease and degradation if they had been grown under a canopy of smoke. She started wondering about the varietal difference in the plants’ response to the smoke, and how the heavy smoke affected yields.

“I noticed that some potato plants just kept living, and others appeared to suffer under the canopy of smoke.”

It took a number of years to get the right research team together, and even more to fund it. But Waxman believed in the importance of the study. “Idaho is well known for growing potatoes and we want to maintain the quality of the potatoes produced and the quality of the Idaho potato name,” she said. “So if we can help growers choose a variety that is more resistant to the smoke impact, then it’s better for our industry.”

Last year, researchers planted the first trial plots, over which Thornton simulated wildfire smoke using materials native to the region such as wood chips and pine needles, exposing the potato fields to several hours of smoke a day starting in mid-July through the third week of August. “That’s when we are more likely to have wildfire smoke, and we’re trying to mimic actual conditions as best we can,” explained Thornton.

The current study is focused on three French fry cultivars: Russet Burbank, which makes up almost half of all plantings in the state; Clearwater Russet, a new variety that’s popular for its heat resistance; and Alturas Russets, a late-maturing and high-yielding potato. Preliminary results already show that certain varieties might fare better than others. When exposed to heavy wildfire smoke, all three varieties had a decrease in marketable yield. Russet Burbanks responded by becoming misshapen, which keeps growers from fetching a premium price. Clearwater Russets yielded smaller potatoes.

Potatoes being exposed to smoke treatments.

·Photo provided by Mike Thornton

Thornton will fine-tune and repeat his experiment again this summer, after which he hopes to offer farmers and processors suggestions for the best cultivars to plant during smoky years. “We don’t want to just tell the industry ‘Hey, you got a problem when it’s smoky.’ We want to be able to say ‘okay, if smoke is going to be a constant issue, here’s something you could consider,” he said.

On the chemistry side, MacDougal is looking at how smoke exposure might affect potatoes’ storage resilience, including their sugar levels, which are key when it comes to achieving the perfect fry color — and there are very strict criteria for color that potatoes need to meet during processing, as researchers are well aware of when it comes to crafting the perfect potato chip. “When you have a canopy of smoke and you have a lot of subgrade potatoes — they’re not the right size, they’re not the right shape — they get rejected,” he said. “If they go through the parfried process, after they’ve been washed, after they’ve been peeled, after they’ve been sliced, and then they get fried, they can gray. And that graying means that they can’t be sold. So you lose again, economically, if your processed potato is compromised.”

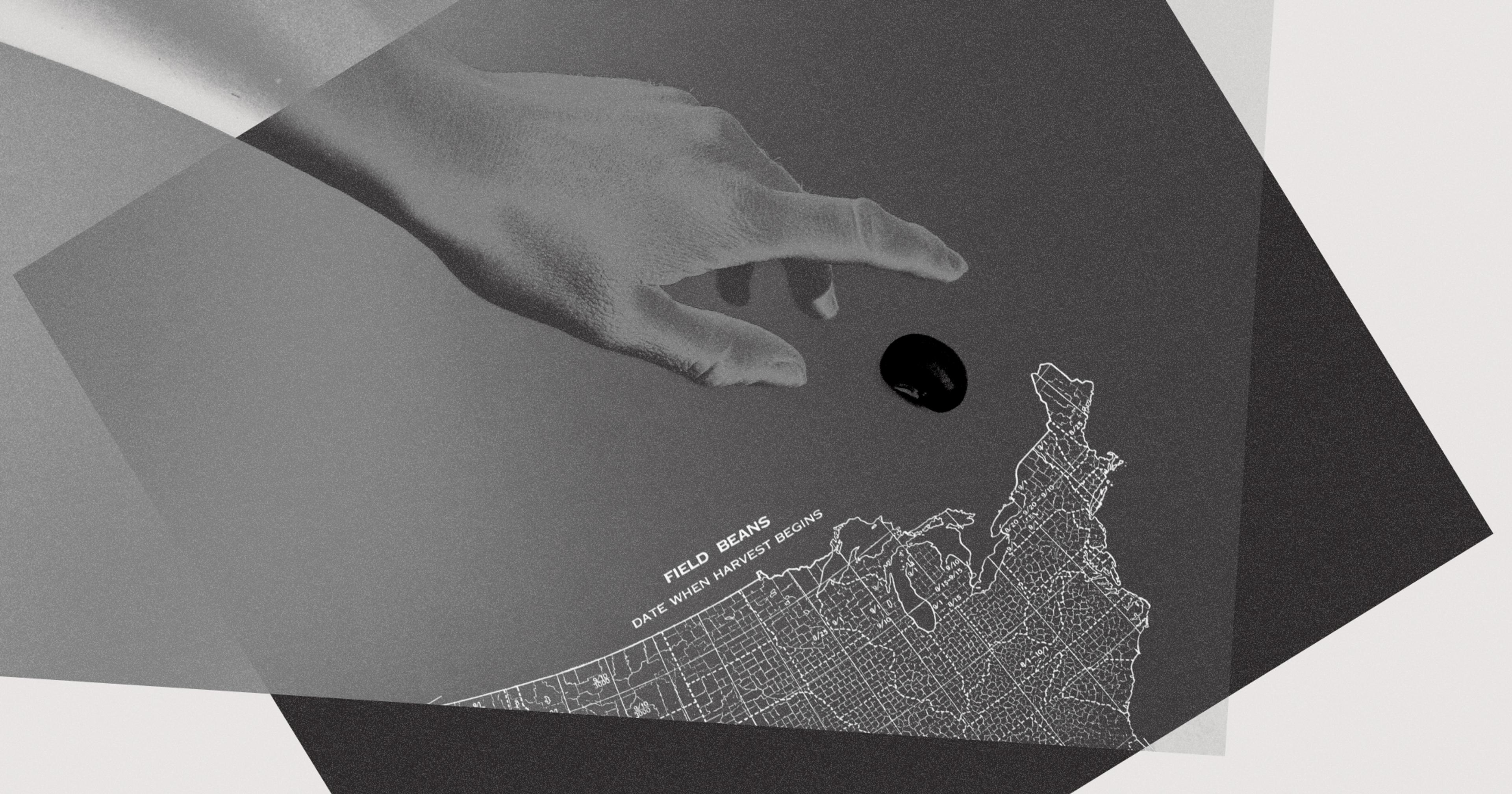

While he hopes the study’s findings will have a positive impact on Idaho’s potato industry, MacDougal also sees a growing need for expanding the body of wildfire smoke-related research in order to better understand how it affects other plants and livestock. “What we’re seeing is a greater number of extreme events. When there is a wildfire, it’s big, and the influence and impact is severe,” he said. “We picked potatoes [to study] because in Idaho, there’s appreciable funds to support that. But it definitely extends to a multitude of other crops.”