In the face of repeated, record-breaking dry seasons, farmers are exploring more drought-resistant crops, while researchers scramble to edit their genes.

Graphic by Ali Aas

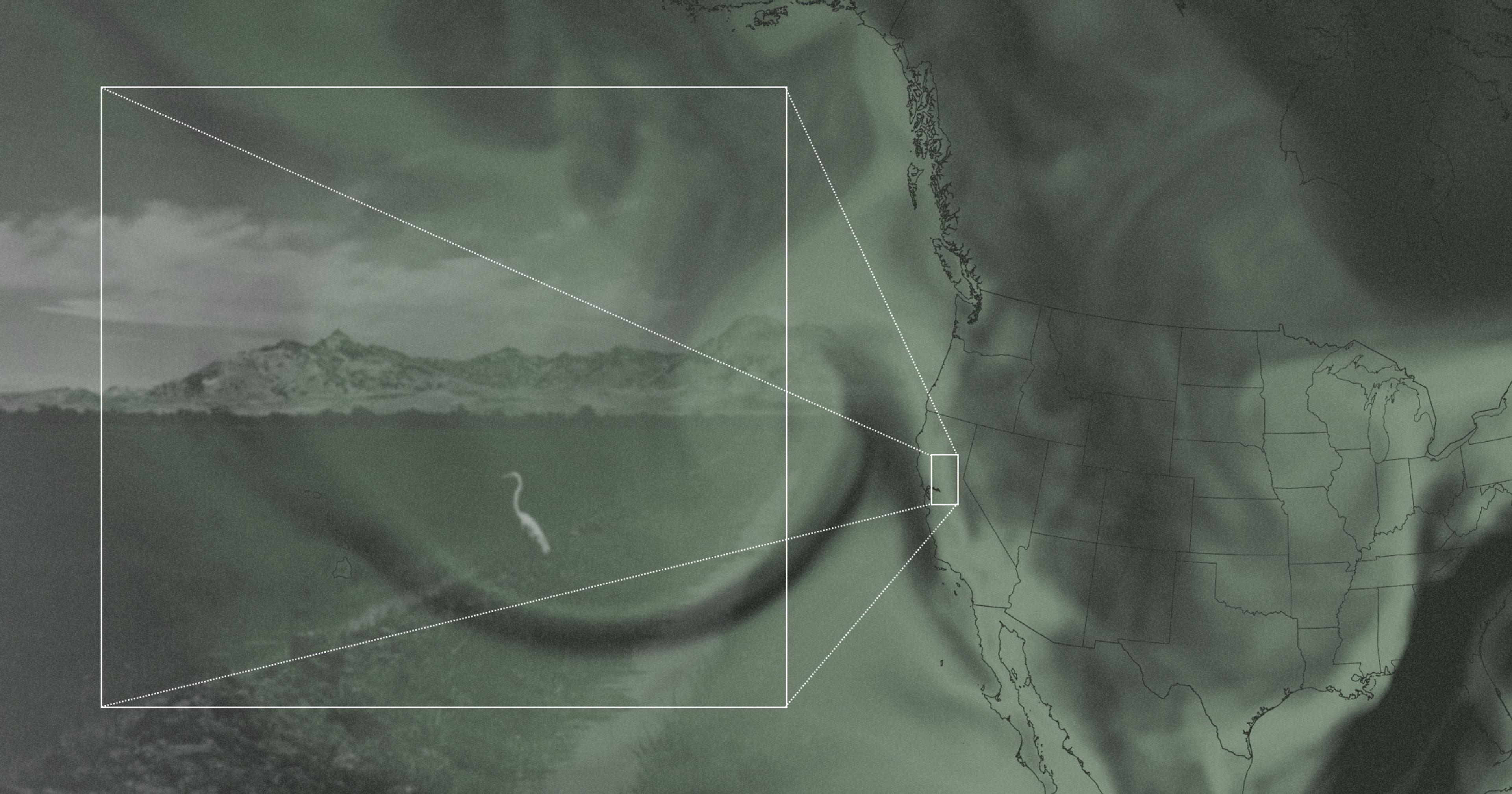

In the summer of 2022, row crop farmer Vance Ehmke looked out at his fields of wheat, rye, and triticale and only one word came to mind: dry. Kansas was in the midst of a record-setting drought, and Ehmke’s farm in Healy would see only 8.75 inches of precipitation that year — less than half of its annual average. It was “pure, bone-crushing dry weather,” according to Ehmke.

In Ehmke’s industry, rain is money. Without it, crops don’t grow, seeds don’t germinate, land is wasted. And Kansas wasn’t the only state suffering through last year’s drought. 2022 was the third-driest year in U.S. history, and the combined Western and Central droughts cost the country $22.1 billion. Globally, drought remains the primary cause of agricultural loss and is a major threat to food security.

To keep farms afloat, many farmers are turning to drought-resistant and drought-tolerant crops. Lima beans, jet barley, kamut, Lebanese light green squash, and more are naturally resistant to dry, hot weather. Some widely used grain crops, like triticale and rye, also offer natural drought resistance. Triticale, a cross between wheat and rye, needs less water overall and can be grown through the cool months of the year. Rye is similarly accustomed to low rainfall, hot weather, and sandy soil. Used in both human and livestock feed, grain crops are the main source of energy worldwide.

Cross-breeding or selecting drought-hardy genes produces tougher, more resilient seeds. For example, breeding winter-hardy rye and fast-emerging spring triticale can create long-lasting, drought-ready grazing crops. Ehmke farms and sells wheat, rye, and triticale blends with drought-resistant properties. “One of the ways to clap back at global climate change is through planned breeding,” stated Ehmke.

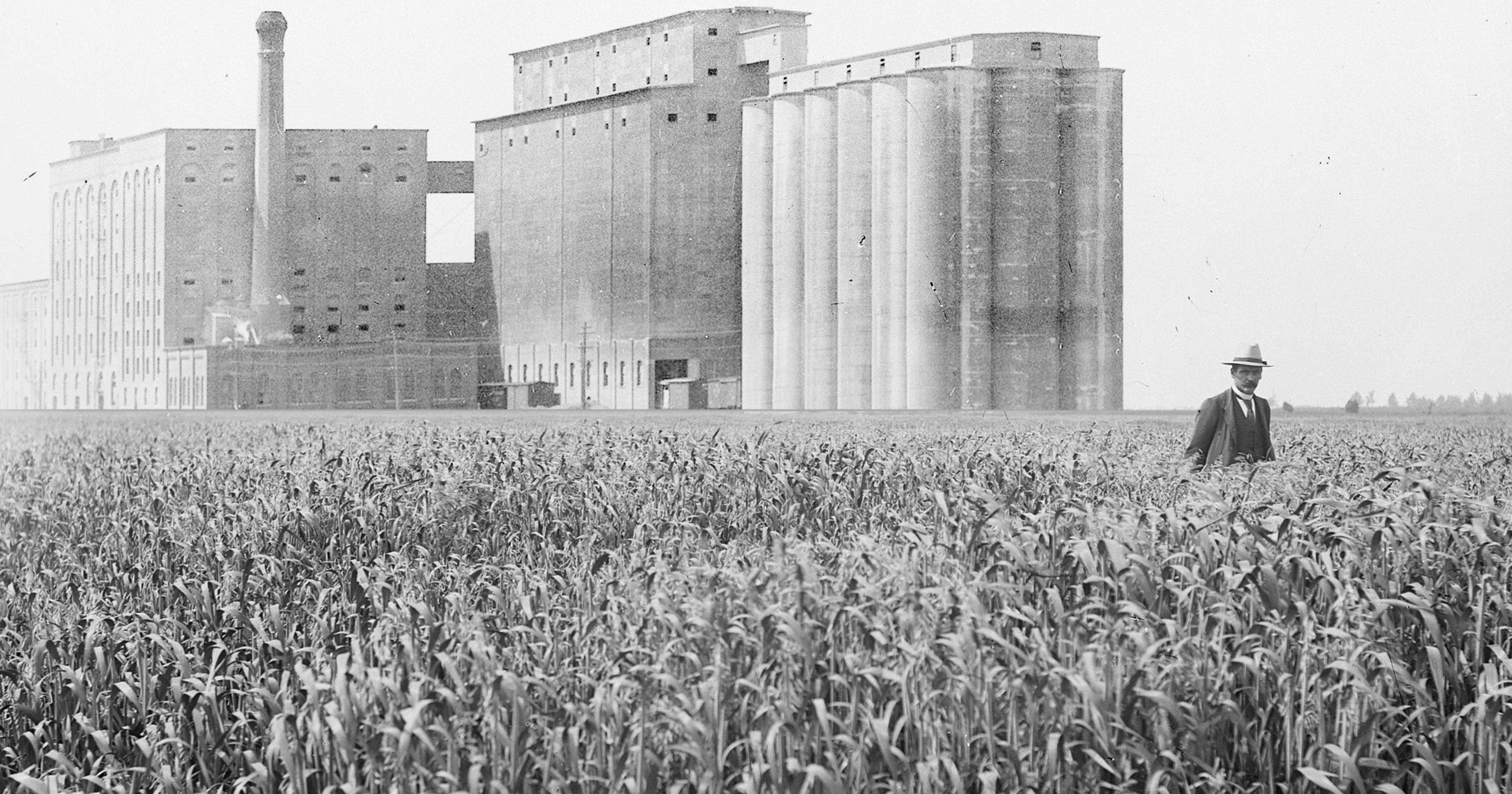

Researchers also are working to make traditional row crops like corn more drought-resistant through gene editing, genetic engineering, and selective breeding. Corn is traditionally very susceptible to drought, due to its small root systems and sizable water requirements, though some varieties fare better than others. Carlos Messina, professor of horticultural sciences at the University of Florida, and a senior scientist at Corteva Agriscience, studies drought-tolerant corn and gene editing.

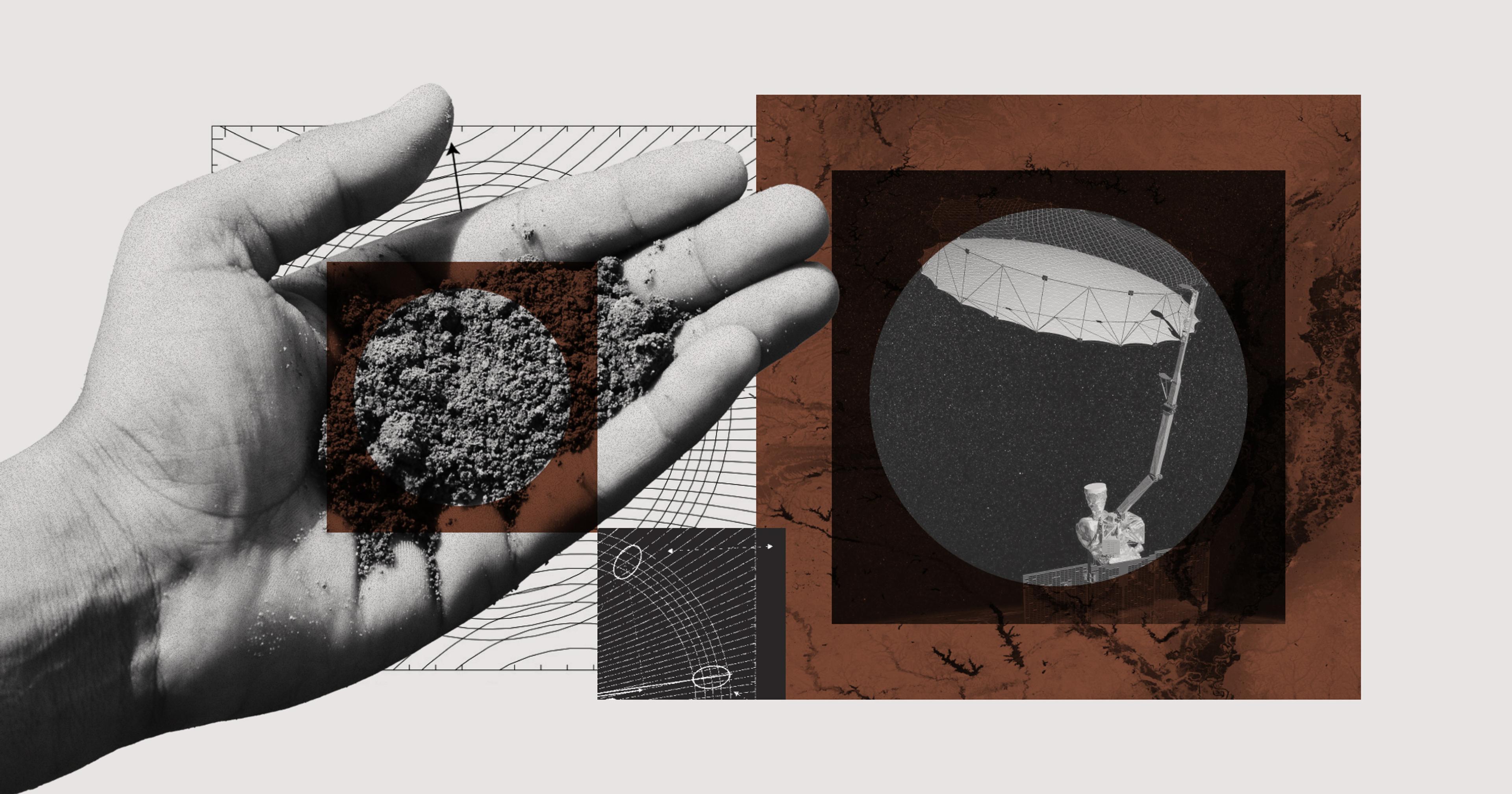

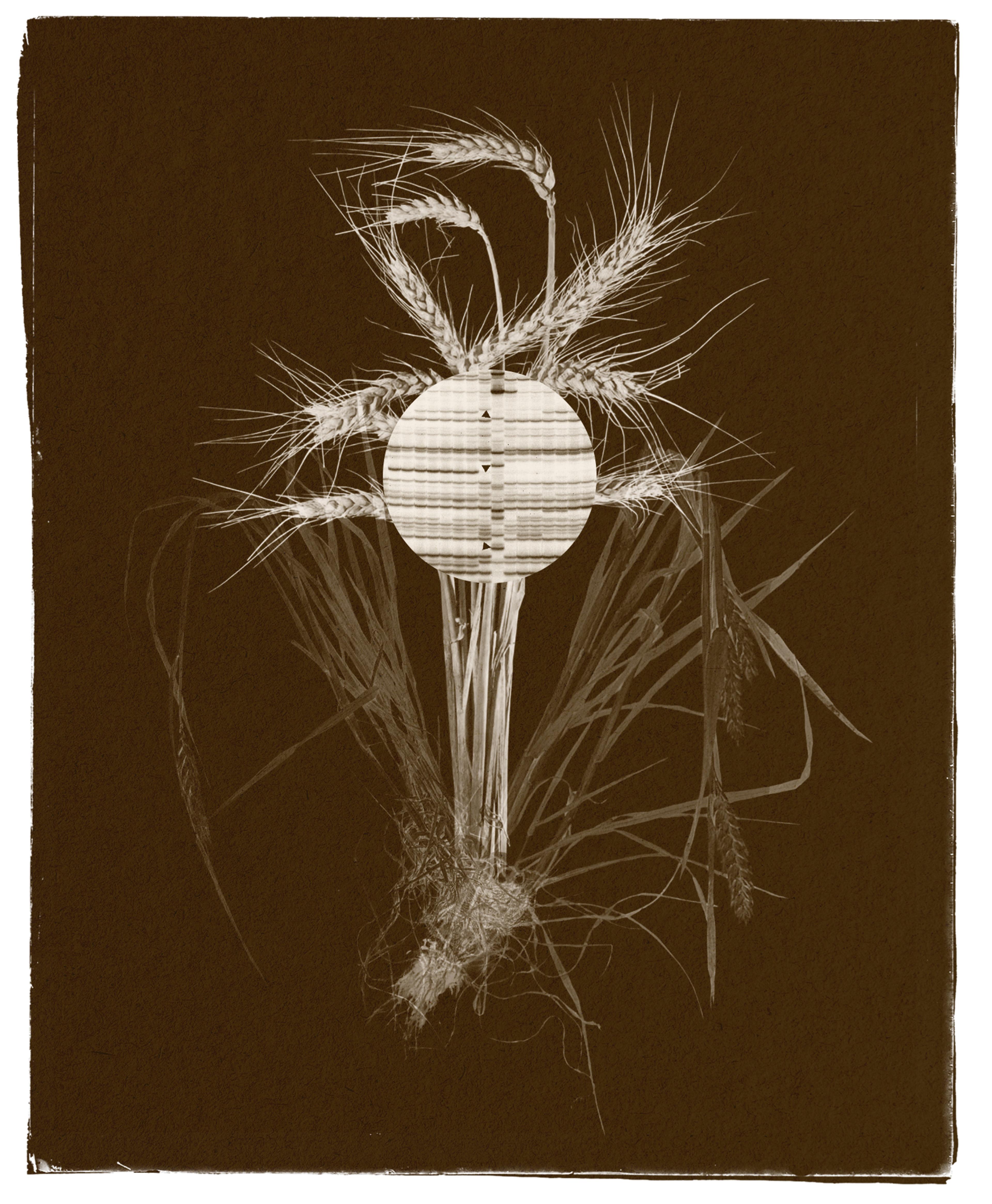

Messina explained that gene editing differs from genetic modification of plants, often referred to as genetically modified organisms or GMOs. Gene editing involves fine-tuning a plant’s DNA, which is essentially the instructions that tell a plant how to grow. It’s similar to what happens in nature, where plants slowly evolve to survive in different environments. If you need a crop to better withstand drought conditions, you might tweak its DNA so it grows longer roots. Or, you could ensure that its reproductive female flowers sustain longer during dry periods. “Gene editing just speeds up this process using biotechnology,” said Messina. “You’re mimicking what nature is already doing.”

Peggy G. Lemaux, a researcher at University of California, Berkeley, who’s been studying genetic crop improvements for over 30 years, argues that every plant is genetically modified, in some way. Natural mutations and generational advancements are just slower, natural iterations of the same science. “With editing, you can make that modification directly in the variety you want to use. It’s much faster, and genetically it’s not any different,” she said.

It’s worth noting that tweaking a plant’s genes to help it survive drought isn’t always straightforward. Drought resistance in plants involves various factors, such as the timing of drought and the plant’s size. It’s not always clear which traits do what.

“One of the ways to clap back at global climate change is through planned breeding.”

As well, droughts — and their effects — change every year. Jonathan McFadden, research economist at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), noted that dry weather and lack of water are only surface-level symptoms of drought. Other problems, like pests and weeds, can create double-stress environments. “When this happens,” he added, “it’s less likely you’ll get a good [crop] outcome.”

McFadden agreed that singling out drought-tolerant genes can be difficult. “There is not one gene that is responsible for how the plant responds to drought. Or even a set of genes — it’s very complicated.”

Overall, however, drought-resistant varieties can improve yields, said McFadden. He explained that the vast majority of drought-tolerant corn currently farmed in the U.S. has also been genetically engineered for other traits like insect and glyphosate resistance. Because of this, these varieties tend to perform better under mild to moderate stress conditions than non-engineered varieties.

For farmers, drought-hardy crops can offer resilience, survival, and potentially some profit. “Growing triticale, you make more money than with corn,” said Ehmke. His crops and seeds are generally sold as cattle feed, a market that values high protein content and steady supply. “You use a lot less water. Part of that is because corn grows in the hottest months of the year when you have high evaporation loss.” A crop like triticale, which can be grown with low water in the cold season, is especially attractive in states like Kansas, which is rapidly running out of water.

Drought-resistant corn has been a popular crop in the traditionally dry western Corn Belt, both in genetically modified and non-genetically modified varieties. However, the most recent USDA data, which only spans to 2016, found drought-tolerant corn made up just 22 percent of total U.S. planted corn acreage.

Corn and soy remain top sellers in the U.S. However, recent data from Kansas State University covering northwest Kansas, where Ehmke operates, found that soy and corn offer meager returns for farmers, when compared to more profitable drought-resistors like wheat and grain sorghum.

“There is not one gene that is responsible for how the plant responds to drought.”

Both Messina and McFadden believe there is more to creating a drought-resistant, climate-ready farming industry than just editing crop genes, or selling new seeds. Conservation or no-till practices, as well as reducing greenhouse gasses emitted from agriculture, will also be necessary.

Traditional breeding methods should not be understated either, said Messina. Tactics like mass selection, recurrent selection, and top crossing have been used for a long time to improve drought tolerance. While these methods may not result in big, immediate breakthroughs, they can lead to steady progress over time.

Still, gene editing will continue to play a significant role in protecting crops from climate change. “The promises are huge,” Messina stated, “but it needs to be done responsibly. This means understanding the biology of plants before we edit them.“

Even now, farmers like Ehmke feel advances in gene editing are moving rapidly, and some are having trouble keeping up. “There’s a new wheat variety every two to three years,” he said. McFadden calls this the “R&D treadmill.” As pests and conditions evolve, you have to fix your sights on next year’s variety, and the variety after that. Whether it’s weeds, insects, water stress, or heat stress — the goalpost is always moving.

Wise farmers are paying attention to university data, finding the highest-yielding drought-tolerant varieties, and adapting quickly, said Ehmke. “Farming is a mature industry characterized by extreme competition and tight profit margins,” he declared. “If you want to stay in the game, you have to adapt immediately.”

Urgency is the name of the game in the ever-drying American plains. All evidence points to an uncomfortable truth: Droughts are only likely to increase. Ehmke’s advice? “Adapt or die, that’s where we’re at.”