Ranchers will try anything to keep wolves away from livestock. Could an aerial approach be the answer?

At first, the wolf was intrigued by the strange, buzzing creature flying toward it. Dropping into a playful stance, it considered whether the drone overhead was something to play with or, at the very least, eat.

That was not the response that the USDA’s Wildlife Services “night watch” team, positioned nearby, was looking for. It was August of 2022 in southwestern Oregon’s Klamath Basin, and the group was testing whether small, remote-piloted drones might be effective at detecting and scaring wolves away from cattle.

It had been a tough period for conflict between wolves and livestock. Over the preceding three weeks, the notorious Rogue Pack had killed a cow just about every other night. “It was really bad,” said Dustin Ranglack, predator project leader for the National Wildlife Research Center. “And nobody’s happy when that is happening.”

As in most of the lower 48 states, gray wolves are federally listed as endangered in the western two-thirds of Oregon, which means that nonlethal tactics are the only legal option for ranchers hoping to prevent wolves from preying on their livestock. Since 2018, state and federal wildlife agencies had been conducting “night watches” in the area, patrolling hotspots of wolf activity on foot and in all-terrain vehicles, and using handheld thermal cameras to scan for predators entering cattle pastures. If detected, they’d deploy an assortment of tools to scare the wolves away, including cracker shells, noisemakers, and nonlethal ammunition.

The hands-on approach was relatively effective, but trees and uneven terrain presented a visibility challenge. The inspiration to try drones came from an unlikely source. “Some folks were out trying to find Bigfoot using drones with thermal cameras,” said Ranglack. “We thought, boy, that’s actually a good idea.” Drones might enable the night watch to detect wolves sooner. But personnel at Wildlife Services, which in recent years has directed more resources toward nonlethal approaches, wondered whether the drones themselves might be able to directly haze wolves away from livestock, reducing the agency’s need to intercept them in person.

That night in 2022, the drone’s pilot flew it away from the playful wolf and back to base, where a speaker was attached to the aerial unit’s setup. As the wolf began to approach a group of cattle, the drone flew to it again, this time with the pilot yelling at the wolf through the speaker overhead. Spooked, it ran off immediately.

Everything But the Kitchen Sink

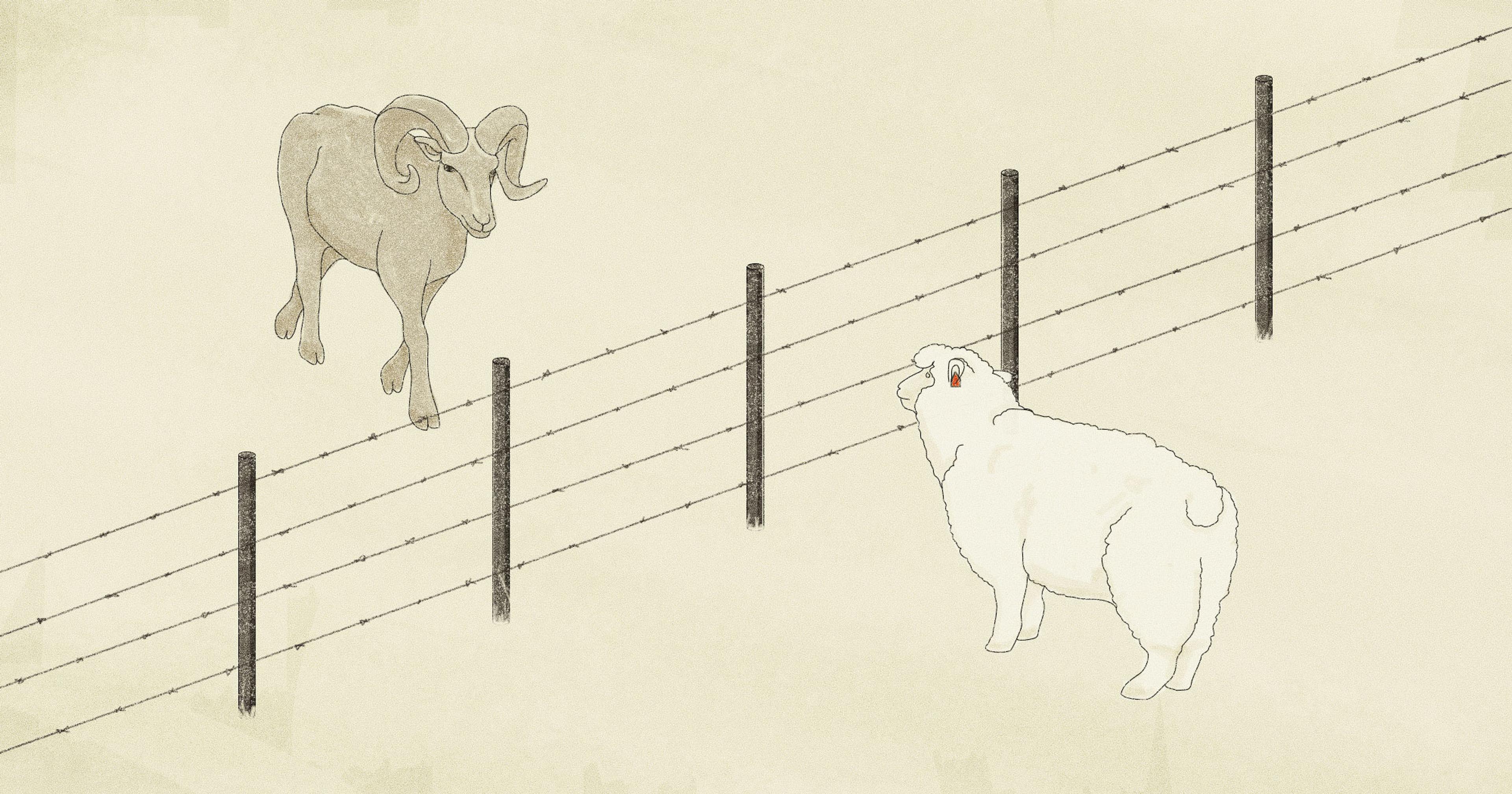

Before gray wolves were protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1974, they were nearly exterminated through a government-sponsored campaign of trapping, poisoning, and shooting. Today, wolf populations are rebounding across the Western U.S., driven by natural repopulation, as well as reintroduction efforts that have seen wolves intentionally released in areas such as Yellowstone National Park and, most recently, Colorado’s rural Western Slope. It’s a major win for conservationists, but many livestock producers view it as an alarming turnaround, particularly if they find themselves on the receiving end of a persistent predation issue.

Seeking a solution, ranchers and wildlife agencies have tested and deployed a diverse arsenal of equipment and strategies, from motion-activated floodlights to noisy speakers to the occasional inflatable air dancer. “We’re seeing a lot of uptake in these practices with people who may not be excited about wolves on the landscape, but who recognize that they’re here to stay,” said Shawn Cantrell, vice president of species conservation and coexistence at the nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife, which promotes strategies for living alongside wolves through community outreach and advocacy.

“Some folks were out trying to find Bigfoot using drones with thermal cameras. We thought, boy, that’s actually a good idea.”

Cantrell has been working on issues around human-wolf interaction for over a decade. He said that the single most effective nonlethal tool is human presence. Range riding, a practice of patrolling and monitoring herds on horseback or ATV, seen as an effective approach, and new agency-funded range rider programs are popping up in states such as Colorado. Livestock guardian dogs are another low-tech solution. But both methods can be costly and require specialized training for dogs and humans alike.

Another highly effective tool is fladry, lines of brightly colored flags that are attached to a wire and strung around grazing land to form a visual barrier that is offputting to wolves. Multiple studies have demonstrated that fladry works, but only if used sparingly, for about six weeks at a time. “Wolves tend to be very inquisitive, and they’re also very smart,” said Cantrell. “After a while, they will get accustomed to any particular nonlethal tool, and at some point they’ll test it.”

Habituation is one angle that Ranglack’s team monitored in their experimentation with drones. So far, he said there’s been no evidence of wolves getting comfortable with them. In fact, the tool may be getting more effective. “That first wolf, when we approached it with the drone, wasn’t afraid of it at all,” he said. “Now, the wolves in this area have had exposure to the drone, and they will often already be moving away when we approach them with just the drone’s rotor noise. They’ve already come to associate the drone with people, and we’re not necessarily having to use the human voice, or recorded gunshots, or fireworks sounds, or whatever else.”

Speaking Their Language

Sara Nozkova has a vision for a future where new technologies aren’t limited to scaring animals away with loud noises and flashing lights. She’s the CEO of Flox, a Swedish company that’s working to combine artificial intelligence with wildlife science for a more holistic approach to deterrence.

This fall, Flox will begin selling its first product, the Edge unit, which is designed to attach to fence posts and repel wildlife using AI-powered image recognition and a proprietary set of bioacoustic deterrents. “It’s kind of our core technology, so I cannot say too much, but the idea is that we kind of speak the language that they understand,” said Nozkova. Flox works with wildlife researchers and biologists to learn and adapt from the animal responses it receives on the spot. “If we see that there isn’t the right reaction with one sound, we go directly to the next one, so the AI is learning the behaviors and how to trigger the right reaction.”

“It’s become a staple for wolf conflict prevention, especially in southwest Oregon.”

Nozkova said this approach mitigates the issue of habituation. “Based on the trials that we’ve been doing, not only do we not see any habituation, we actually see that we can teach animals to avoid different areas.” Predator deterrence is just one application of the technology: Flox has trialed the Edge device in airports, railways, and farms, and says it’s so far repelled 25,000 animals, including deer, elk, and wild boars.

Drones are the next frontier of Flox’s product development. “We’ve been experimenting with drones since 2021, because we believe that that’s the future,” said Nozkova. To fulfill customers’ needs, she said a drone would need to operate autonomously, patrolling around the clock — especially evenings and nights when animals are most active — and returning to a charging station as needed. “It’s something that’s definitely possible, but it’s quite complicated.” Autonomous drones are tightly controlled by the Federal Aviation Administration, and regulatory hurdles abound.

Nozkova says her company is continuing to test the concept while waiting for the next wave of drone technology to lower costs and enable further innovation. For now, multiple Edge units can be installed to form a virtual fenceline that approximates what a drone might be able to cover. “With drones, we will unlock the potential to cover even larger areas,” she said.

Peace of Mind

While autonomous drone patrols may be a long time coming, there are plenty of limitations to using drones to haze wolves today. Battery life allows only for a short window of time before drones need to recharge, and topographic elements such as tree cover or rocky areas can present a challenge. (Seen from an overhead thermal camera, a sun-warmed rock can look like a wolf.)

Cost is another major issue: Each drone used by Wildlife Services costs between $10,000 and $20,000, and flying them requires at least one trained pilot and one visual observer to keep eyes on the drone, ideally with a fully charged backup on hand. “The cost of this technology is not at a point where it is feasible for each individual producer to be able to go out and buy something like that,” said Ranglack.

“It’s going to take time for the technology and the price point to catch up. But it would give that producer peace of mind.“

Still, he is positive about the technology’s potential. After the night watch introduced drones in the Klamath Basin, livestock predations went from one every other night, to just two over 85 days. Though more experimentation is needed, “It’s become a staple for wolf conflict prevention, especially in southwest Oregon,” he said. Wildlife Services is now growing the program, training more pilots, acquiring more drones, and working with state agencies to test the approach in Colorado, Arizona, and Northern California.

Someday, Ranglack would like to see a future where every producer could buy an affordable drone that could be programmed to patrol an area that covers all of their livestock. At a minimum, he envisions a system where the drone could assess whether there’s a threat or not, and send out either an “all clear” or “threat detected” message with a location pin, allowing people to respond quickly.

“It’s going to take time for the technology and the price point to catch up,” he said. “But it would give that producer peace of mind of knowing that there is something out there watching over their herd or their flock while they sleep at night.”