New research flags air pollution from agriculture and wildfires as a dementia risk.

Olivette Farm, a 5-acre market produce operation outside of Asheville, North Carolina, sits well over 400 miles south of the Canadian border. So Lauren Penner, who manages the farm with her husband, Daniel, didn’t think much of the haze that had settled over Olivette from Canada’s wildfires earlier this year.

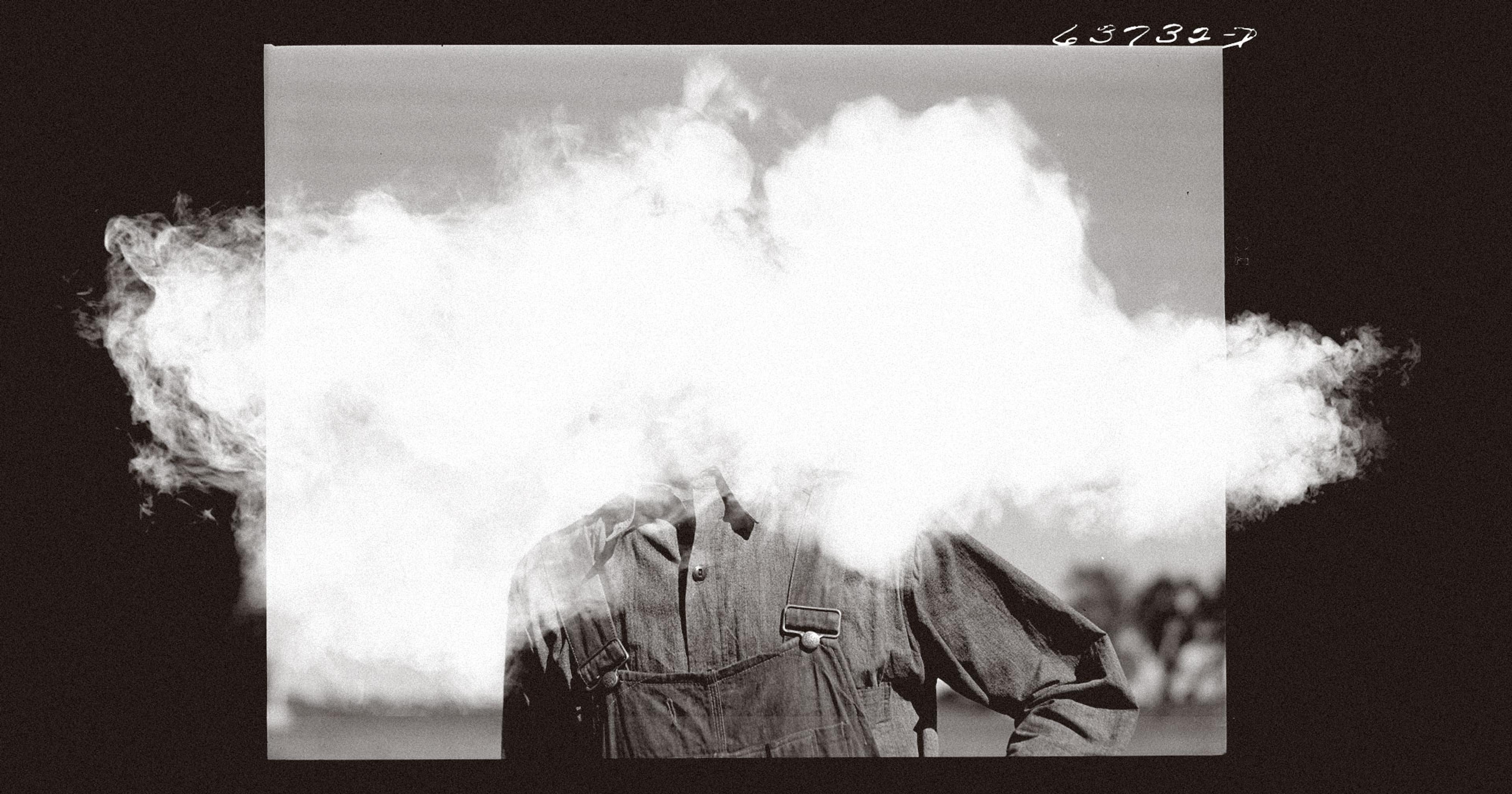

“There was just a film in the air. You could tell there was a contrast between the mountains and the sky, because the color of the sky was so obviously smoky,” Penner recalled. But there were weeds to pull and veggies to harvest, and she put in a full day of work regardless.

“Oh, it’s so far north, it can’t affect us too badly,” Penner remembered thinking. Her chest felt a little tight as she went to bed; she chalked it up to the general exhaustion of summer farming.

When she woke up the next day, her brain rang with a pounding headache, and her limbs felt as sluggish as if she’d been drinking the night before. Those symptoms weren’t normal, and she realized that her hours of inhaling the wildfire-tainted air were to blame. “It’s pretty wild. I’ve never experienced that before,” she said.

“Smoke brain” — brain fog associated with increasing wildfire pollution — made headlines this summer as a symptom beyond the expected lung and heart effects. Farmers generally don’t have much choice about whether to go outside when wildfires are blazing, and that makes them particularly susceptible to air pollution — not only from burning trees in the Canadian forest, but also from the results of their own work. Tilling, planting, and harvesting fields kicks up substantial amounts of dust, while fertilizer and animal waste release ammonia, which combines with other pollutants to form fine particles.

A new study recently published in JAMA Internal Medicine suggests that farmers, along with everyone else who breathes air contaminated by wildfires and agriculture, may have more to worry about than Penner’s hazy hangover. A team led by scientists from the University of Michigan found that exposure to pollution from those two sources is especially likely to increase the risk of developing dementia.

The researchers looked at a nationwide survey that tracked the cognitive health of nearly 28,000 U.S. residents over 50 years, then correlated new cases of dementia during the survey period with levels of fine particulate matter at participants’ home addresses. That type of pollution, known as PM2.5 — particles less than 2.5 microns in diameter, or about 35 times smaller than a grain of sand — can enter the lungs and bloodstream and is known to cause a variety of health problems.

Using a sophisticated computer model, the scientists estimated how much PM2.5 at a given location was due to each of nine different sources, such as traffic and coal-burning power plants. That let the team analyze the degree to which increases in each pollutant were tied to greater dementia risk.

When they crunched the numbers, agricultural and wildfire-related PM2.5 clearly stood out as the most concerning. Regarding agricultural pollution in particular, lead study author Boya Zhang stated that the likelihood of new dementia went up by 17% for every 1 microgram per cubic meter in 10-year average exposure before the case. (For comparison, the federal Environmental Protection Agency’s standard for annual PM2.5 levels is 12 µg/m3. During the peak of the Canadian wildfires this June, the average U.S. resident faced 27.5 µg/m3.)

Data from epa.gov

The study’s authors point to previous research associating ammonium with dementia, which they say may be related to agricultural emissions. They also suggest that the use of pesticides, many of which are known to be neurotoxic, could explain the agricultural link. Wildfires, they add, “release components that are likely to be highly toxic because they incinerate natural and synthetic materials in an uncontrolled manner.”

Previous studies have shown that residents of rural areas are at greater risk for cognitive decline. “The difference in exposure to agriculture and wildfire-related PM2.5 might partially explain the disparities,” Zhang said.

The science tying air pollution to mental health is fairly recent, said Marc Weiskopff of Harvard University. He wasn’t involved in Zhang’s study, but he published a review of available research on the pollution-dementia link earlier this year, all of it conducted over the last decade.

“I think generally the attention was on effects on the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, because these can be obviously, directly impacted by air pollutants,” Weiskopff explained. “There has been increasing understanding now, though, that air pollutants can potentially go much more directly to the brain through the olfactory system, bypassing the lungs and circulatory system.”

The U.S. has made some headway toward reining in PM2.5. Since 2000, overall levels of fine particulates have decreased by 42%, largely due to cleaner vehicles and power plants. The EPA has proposed reducing its annual standard for PM2. to 9-10 µg/m3, which the agency estimates would prevent up to 4,200 premature deaths in 2032 alone.

But that trend could be reversing, and primarily through the PM2.5 sources flagged as dementia risks by Zhang and colleagues. Climate change driven by the burning of fossil fuels has made wildfires more intense; a recently published study in Nature found that those stronger fires have eliminated about 25% of the country’s progress in reducing PM2.5 since 2020.

Climate change may also increase agricultural PM2.5. As temperatures get hotter, notes a 2022 review in the Journal of Environmental Management, livestock farms are likely to emit more ammonia — a key PM2.5 precursor — especially through manure storage and concentrated animal feeding operations.

“We work through everything, because the farm doesn’t take a break for you.”

Given these challenges, said Harvard’s Weiskopff, scientists need to step up their measurements of specific PM2.5 sources like agriculture and wildfires. Zeroing in on the origins and movement of this pollution would help federal regulators take more targeted actions to protect public health.

“The main issue is that right now, the EPA regulates PM2.5 as a whole,” he pointed out. “You could in theory reduce sea salt levels to reduce PM2.5 and get into compliance with EPA regulations, but that may do nothing to reduce the population risk for dementia.”

Back at Olivette Farm, Lauren Penner said she’s concerned about the potential for more days like those of the hazy summer under a changing climate. But there’s little she can personally do to adapt her work, she said, besides tying a wet bandana over her mouth and hoping for the best.

“Farmers are extremely hard workers, and we have to get a lot done in a short amount of time to make any money,” she said. “We work through everything, because the farm doesn’t take a break for you.”