In the popular imagination, prized truffles come from Europe, foraged from the wild. Here in the U.S. however, more than 200 farms are trying to disprove that convention.

Just over 20 years ago, cultivated truffle farming was virtually unheard of in America. Truffles were an exotic, gourmet crop directly associated with Europe. But that’s changing — and fast. The North American Truffle Growers Association (NATGA), which was established in 2005, estimates that there are currently more than 200 truffle orchards in the U.S. Some experts even suspect the American market will surpass European truffle production in the next few decades.

NATGA’s president Margaret Townsend owns a 25-acre truffle orchard in southern Kentucky, which she planted in 2012. “When I started this project 13 years ago,” she said, “the question was ‘If?’ And I think more and more, the question is becoming ‘When?’ and ‘How much?’ I think we have made that much progress.”

A Crop for Patient People

Foraging wild truffles (truffle hunting) has been the dominant means of truffle collection for most of history, because the science of growing truffles is complex. Few growers are willing to share the details of their process, but the basic recipe alone is fascinating. You start by inoculating tree roots with truffle fungus in a laboratory or nursery. Different truffle species thrive alongside different trees: Black Périgord truffles seem to prefer oak and hazelnut trees, while the white Bianchetto is happiest on the roots of pines.

Next, the inoculated saplings are planted in a very base soil (most truffles require a pH level around 7 or 8) with a light, aerated structure. Truffles grow underground, so they need the space to do so. Proper irrigation is also crucial —truffles like a moist, but not sopping wet, environment.

And then, you wait. For years.

“It seems to take between 8 to 10 years for a tree to start producing its first truffle,” said Olivia Taylor, a grower and researcher with Virginia Truffles, a six-acre farm of hazelnut and oak trees inoculated with Périgords. “It’s definitely for patient people.”

At Burwell Farms, now the largest truffle producer in North America, the owners were told to “expect truffles in 6 to 10 years, if ever,” said plant biologist Jeffrey Coker, president of Burwell Farms.

But three and a half years after the first orchard of inoculated trees was planted, Burwell Farms found its first truffle by accident.

“We weren’t even looking,” said Coker. “Fast forward to our most recent orchard, we knew to look, and we had dogs that were trained to look. In the second year after planting that orchard we found somewhere between 10 and 15 pounds of truffles. In a two-year-old orchard. That’s not supposed to be possible, but it is possible, because we’ve figured out how to farm.”

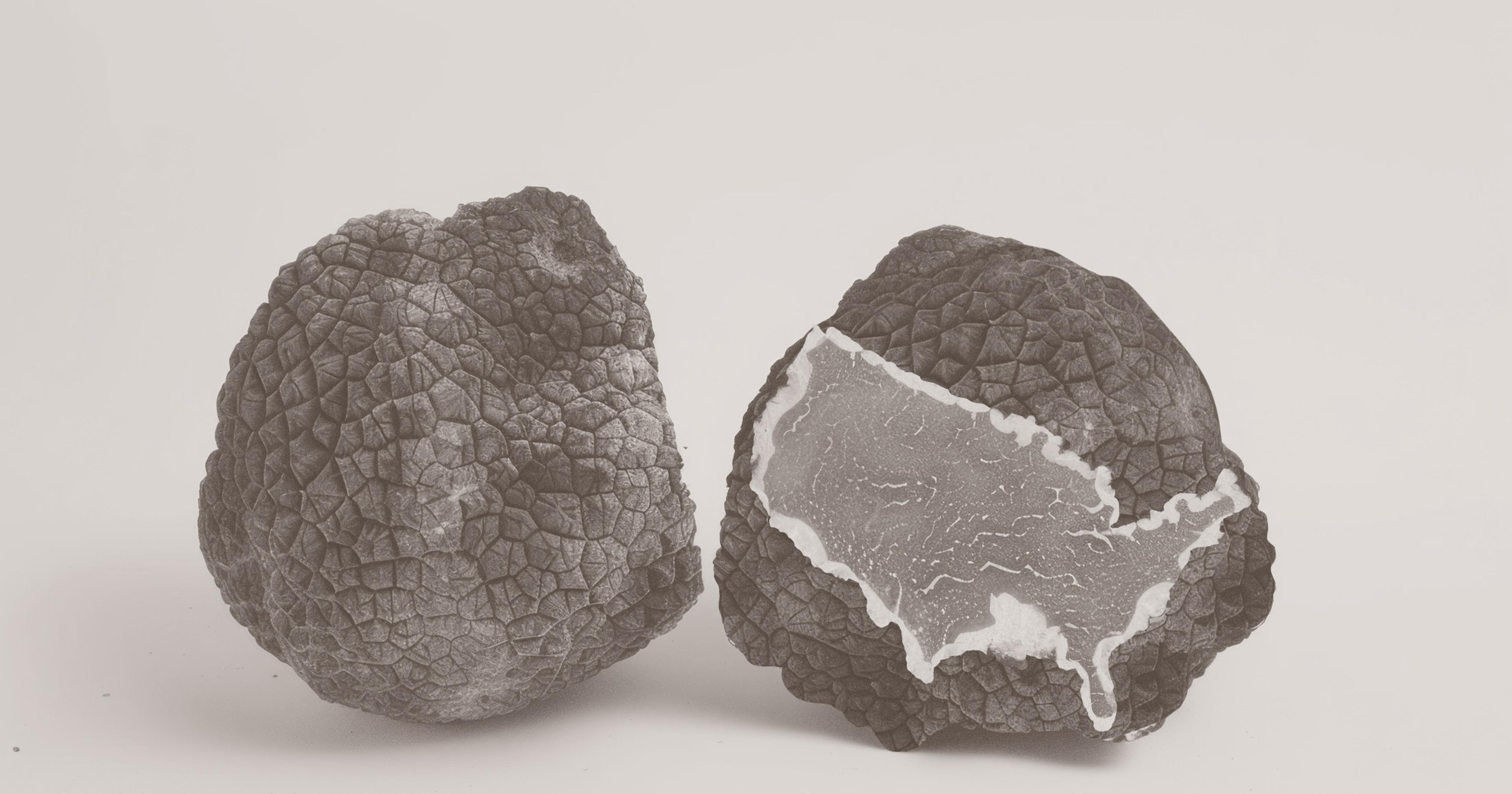

The Truffle Hierarchy: Subjectivity and Dollars

Not all truffles are created equal. There are thousands of different truffle species, including several that are native to the U.S. “Unfortunately,” said Robert Chang, managing director of the American Truffle Company, “none of the native North American species is really worth a lot economically and that’s because they simply don’t have the aroma and the flavor of the European species that have traditionally been prized by chefs.”

The Italian white truffle, tuber magnatum, is widely considered the world’s best truffle, and it routinely sells for up to $6,000 a pound. While valuable, this truffle is significantly more fragile and finicky than other truffle species, so efforts to cultivate it outside of its wild-growing environment have been thus-far unsuccessful — leaving the supply to what is harvested from the wild and keeping the price point high.

The Périgord black winter truffle, tuber melanosporum, is another highly-prized species that typically fetches around $100 an ounce. This is what American Truffle Company focuses on growing with its partners, and according to a 2022 NATGA survey, this is the predominant species grown in American truffle orchards.

But Burwell Farms grows the white bianchetto truffle (tuber borchii) on its orchards of loblolly pine trees. Burwell sells their Bianchettos at $105/ounce, comparable to the market price for Périgords. “We try really hard not to engage in this conversation about which truffle is better,” said Coker. “Truffle aroma is like 70 to 80 volatile compounds all hitting you at once, and people’s genetics are very complicated around taste receptors and things like that.”

“Truffle production in the United States will be dominated by the Southern states.”

Coker said the idea that Périgords are superior in flavor to Bianchettos is a cultural hand-me-down from Europe. “In Europe, [Bianchettos] are easier to find in nature,” he said. “So culturally, it becomes a little bit less prized, not because of the truffle itself, but because there are more of them.”

The Bianchetto thrives in a wide variety of pH levels and soil structures, and naturally grows on the roots of pine trees, which thrive in the southeastern U.S. Black truffles, on the other hand, are “finicky,” said Coker. They are sensitive to changes in pH and soil structure, and the trees they grow with — oaks and hazelnuts — are prone to blight.

“I’d love to say that it was all because of our farming talent and scientific brilliance,” said Coker. “But the biggest thing is just that it’s a better system … that’s easier than those black truffle systems.”

The simplicity of these connections — loblolly pines thrive in the Southeast, and bianchetto truffles thrive on loblolly pines — has led Coker to believe that the southeastern U.S. will lead the way in American truffle farming. “Truffle production in the United States will be dominated by the Southern states,” he said.

The Promising Future for American Truffles

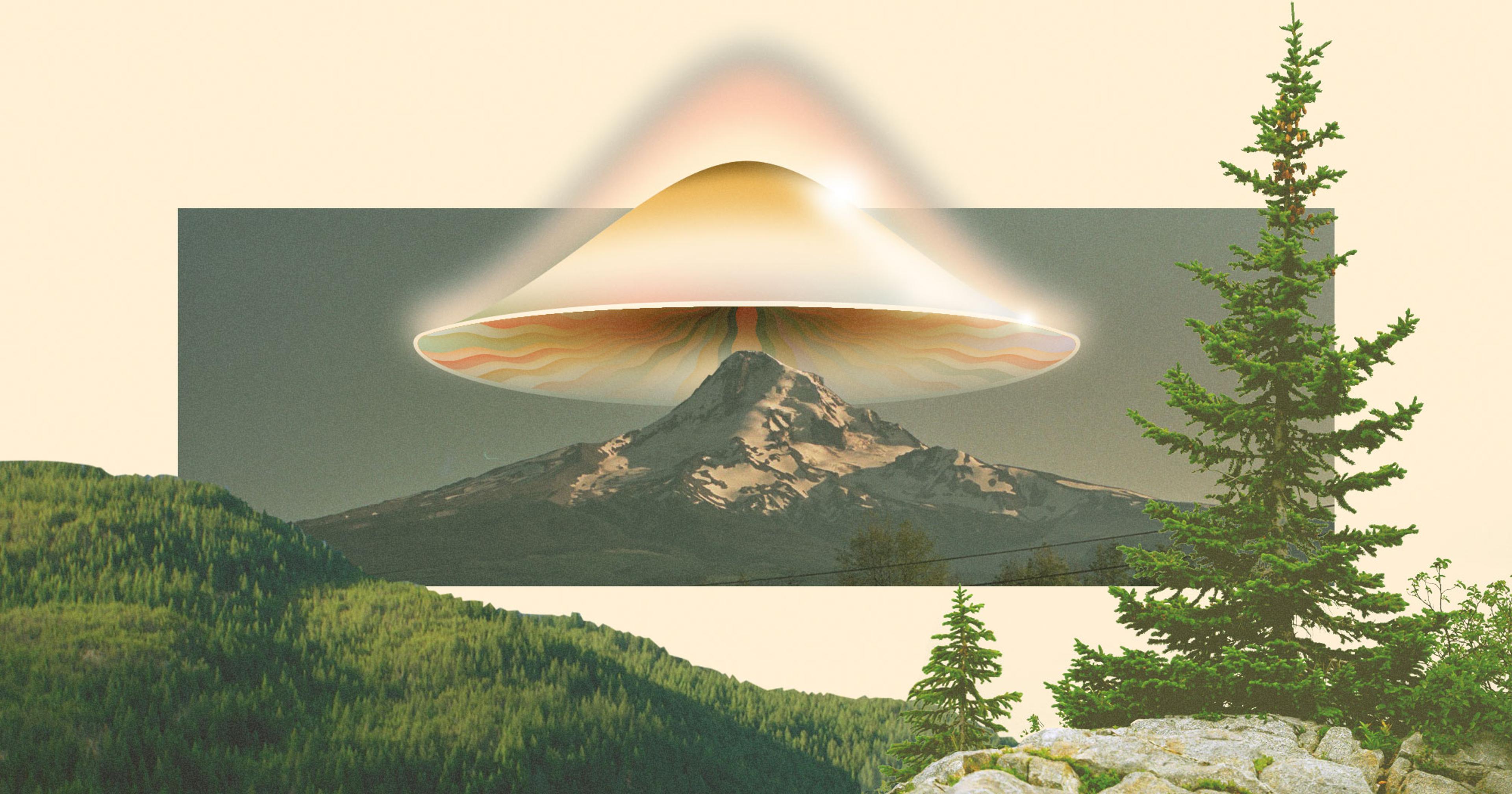

Europe is currently the largest producer of truffles for the global market, but there is evidence this won’t be the case for much longer. Professor Paul Thomas, chief scientist at the American Truffle Company, published an article in 2018 assessing the future of Europe’s black truffle market alongside climate model projections. He predicts a decline of up to 100 percent in European truffle production between 2071 and 2100.

“The conclusion is that within 30 years, the largest producer of truffles, which is Spain, will have gotten so hot and so dry that it would no longer produce,” said Chang, Thomas’s business partner. “It becomes a great opportunity for American truffle producers … to pick up that slack and shift the center of production away from Europe and more to North America.”

Of course, the author of the study has a clear interest in promoting the viability and promise of the American truffle market, but other trends point toward increased domestic success in the coming decades. For one, NATGA is working to obtain specialty crop status for truffles in the U.S., a goal they hope to achieve as early as this year. Specialty crops are defined by the Specialty Crops Competitiveness Act of 2004 as “fruits and vegetables, tree nuts, dried fruits, and nursery crops (including floriculture).” Earning this status would make it easier for American truffle farmers to obtain federal support, which has been crucial to the development of the now-flourishing truffle industries in countries like Spain and Australia.

“If we had specialty crop status, which we’re working very hard to establish, then [USDA] grants and investments would be so much easier for us,” said Townsend. “If you have been established as a specialty crop, your market, your growers — everything is much more clearly defined and there’s less documentation required. It brings credibility to grant applications.”

This status and increased access to grant money will provide an opportunity for more controlled research and development that can improve outcomes for American truffle farms. “Controlled experimentation is not necessarily the norm with truffle farmers,” said Townsend. “We’re so busy trying to crack the code that it’s very challenging for us to be able to run controlled experiments in our own orchards. It’s very, very important that we have researchers working with us who are working across multiple orchards to design those controlled experiments.”

Between climate change and the impending specialty crop status designation, American truffles could very well be poised for a dramatic increase in production and value — thanks, in large part, to the efforts of a small group of passionate, curious, and incredibly patient farmers.