Wine growers are increasingly exploring alternatives to chemical inputs and machine-based farming.

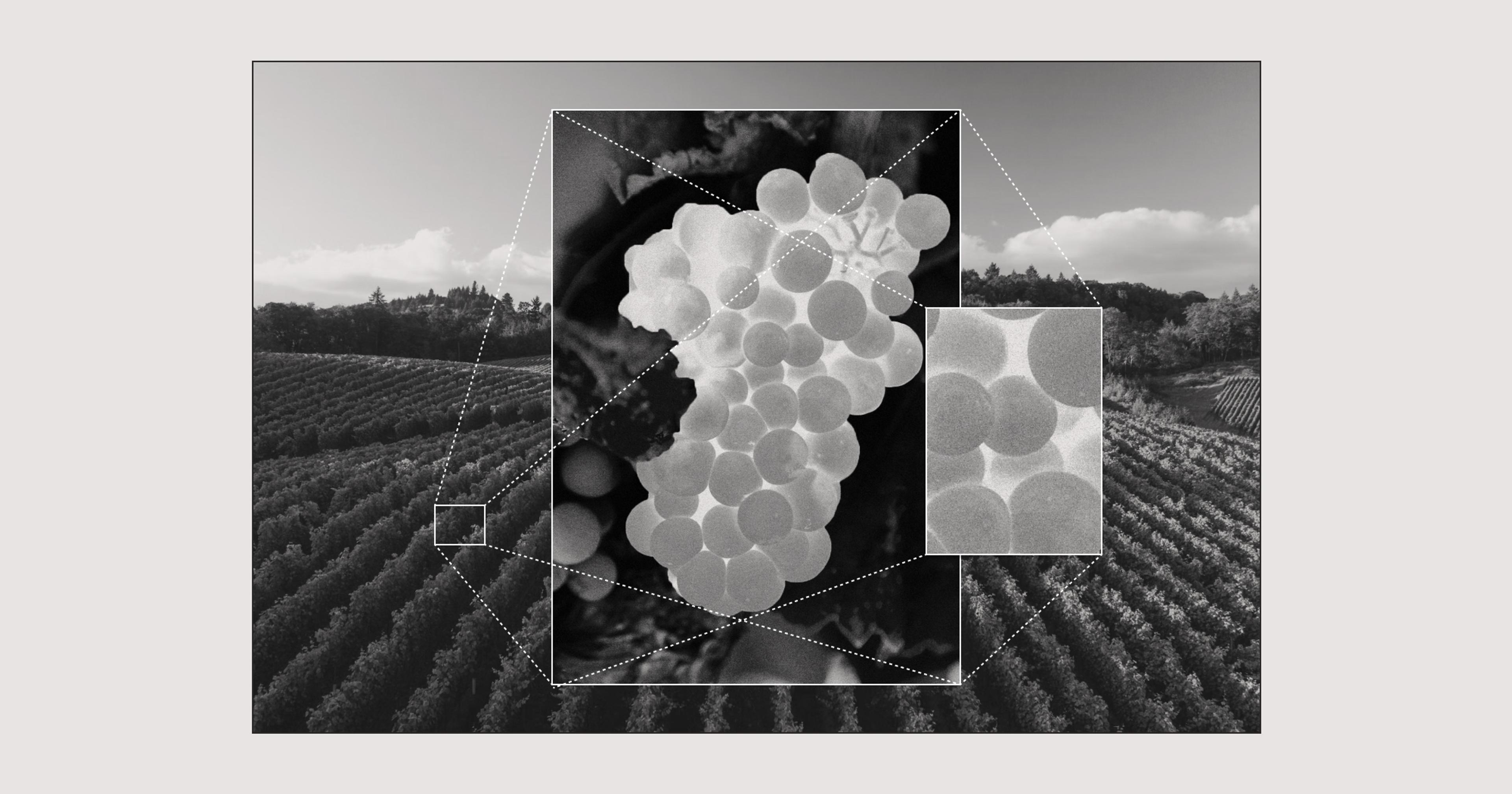

Some crops and places, inevitably, are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Take wine grapes. Scientists writing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences warn that the area considered suitable for growing these grapes could shrink by 56-85% in the coming decades if current warming patterns persist.

In the past few years, winemakers across the globe have faced massive crop losses due to wildfires, freak hailstorms, frost events, and persistent drought. Unusual weather patterns also bring new diseases and pests. You may have heard that the invasive spotted lanternfly, for example, is headed West — after decimating vineyards in 14 states on the East Coast and the Midwest.

While some growers double down and utilize more chemical inputs to keep pests away, others are responding to an abundance of studies that show pesticides not only don’t solve for long-term pest and weather problems, they can contribute to the acceleration of climate change.

In addition, many are eager to reduce tractor passes, or eliminate machines altogether, in a bid to improve soil health and reduce their carbon output — in recent estimates, the EPA reports that off-road agricultural equipment releases about 100,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide.

Obviously nixing chemical pesticides and equipment like tractors is far from a simple procedure. Without alternative, effective, affordable ways to eliminate pests and farm the land in place, harvests would suffer considerably.

That said, the situation is challenging, but certainly not hopeless. Wine growers are finding a surprising array of creative ways to enlist the flora and fauna all around them.

Bring in the Bugs

Daou Family Estates in Paso Robles, California, manages an 856-acre estate; they farm organically, and use cover crops to create habitats for insects, sequester carbon, and control soil erosion, said Daniel Daou, co-proprietor and winemaker.

The team also installed two standalone bug hotels and four small insectaries fixed on end posts dotted across the vineyard to “attract beneficial insects and spiders that will feed on pests,” Daou said. “We also seed a native wildflower blend around our reservoir to attract bees and provide them with an ample supply of pollen.”

This, along with their overall integrative approach, Daou explains, is designed to not only create a more “resilient and sustainable environment for grape growing, which will in turn allow the vines to express their full potential and make better wines,” but to help combat the startling decline in insect populations across the world. (A comprehensive review of 73 historical reports published in Biological Conservation showed that 40% of the world’s insect species face extinction in the next few decades; the main causes are intensive agriculture, urbanization, and pollution due to synthetic pesticides and fertilizers.) It should be noted that while beneficial bugs are being brought in to eliminate harmful bugs in the vineyard, this will not lead to a decline in their populations across the board.

At Treasury Americas, a sprawling collection of wineries across California with 6,000 acres under vine, working “with nature, rather than against it,” is their modus operandi, said Emily Kern, Treasury’s sustainability manager.

Beginning to use insects, wild birds, and/or farm animals instead of chemicals and tractors requires, at the very least, a mental adjustment.

“We avoid blanket spraying of chemical inputs not only for the good of the environment and human health, but because this kind of application also kills off the good insects and bugs that help us care for our grapes,” Kern said. “When you kill off everything, it opens the doors for outbreaks of other, bigger problems.”

Instead, their holistic approach to farming includes recruiting help from the insect and animal kingdom.

“We plant hedgerows and insectary rows to provide shelter, food, and protection for insect predators and parasites that eliminate harmful pests we’d need to otherwise spray off with insecticides,” she said.

Strategically placed insectary rows, planted with flowering plants in bloom from January to September provide stable food, habitat, and protection for large, multigenerational populations of beneficial bugs, Kern explained. They also ensure long-term natural suppression of harmful insects — no chemical intervention needed, or machine passes for pesticide application.

These methods at Daou and Treasury suppress populations of mealybugs, sharpshooters, leafhoppers, spider mites, and other harmful insects. Unchecked, they can spread Pierce’s disease or plant viruses like leaf roll and red blotch.

At Ehlers Estate in St. Helena, California, with 40 acres under vine, the team has erected a worm hotel to help combat California’s daunting drought conditions — the worst the state has faced in more than 1,200 years.

In 2021, Ehlers installed a two-story, rectangular worm unit (about the size of an 8x10-foot rug) that turns unusable wastewater from their operations into gray water that can be used to hydrate the vineyards, explained winemaker and general manager Laura Diaz Munoz.

The system, designed by worm-powered waste-solution company BioFiltro, essentially supplies worms with water that has been “used” in the winemaking process. It contains larger organic compounds like grape skins and seeds that would otherwise make it into the waste stream, according to BioFiltro’s chief impact and sustainability officer Mai Ann Healy.

After breaking down and digesting the wastewater, the worms excrete a microbial-rich casting; microbes from these castings form a biofilm, or a layer composed of billions of microbes and bacteria, which then capture and digest soluble and smaller nutrients in the process water. Over time, the castings build up, and every three or so years, can be removed and used as a beneficial soil amendment.

At peak harvest, the worms can handle 1,200 gallons per day, and this treated water can then be used in dripline irrigation — instead of tapping into California’s strapped supply of groundwater.

Winged Predators Take Flight

Wine growers eager to combat insects and rodents without chemicals are finding allies in the sky — bird and owl boxes are increasingly regular sights at vineyards.

At Chappellet Vineyard, with 104 acres under vine in the Napa Valley, all the farming is done organically to support worker and environmental health, said vineyard manager Andrew Opatz. His team has erected boxes for bluebirds, swallows, barn owls, and kestrels to combat pests. The smaller birds eat insects, while the barn owls and kestrels target rodents, which can feed on grapes and grapevines and disrupt their root systems. One family of owls can eat as many as 3,400 rodents a year.

Opatz hopes to maximize the bird’s bug-nixing power by teaming up with scientists on a comprehensive study of their efficacy this year. Chappellet is working with University of California Cooperative Extension Wildlife and Cal Poly Humboldt “to help us identify the best way to distribute our bird boxes,” said Opatz. “We will be tracking the birds’ flight patterns and examining their diet to study what they are consuming and when they are consuming. The goal of this study is to be able to maximize these natural resources, because creating a balance between beneficial wildlife and pest insects and diseases ultimately also helps us ripen the grapes to the standards we need.”

At Lodi, N.Y.’s, Silver Thread Vineyard, owner and winemaker Paul E. Brock II uses seven chickens to till, weed, and eat insects on his seven-acre vineyard.

The smaller birds eat insects, while the barn owls and kestrels target rodents.

“We will be expanding to 15 to 20 birds this season, and plan to include ducks, geese, and guinea hens,” Brock said. “The chickens are great at tilling the soil around the vines, and geese are great at eating grass. … Ducks and guinea hens are also excellent insect-eaters.”

But like the pesticides many of these creatures replace, they are not a panacea. Brock estimates that their disease control is now “over 90% organic or biological.” But instead of going for organic or biodynamic certification, he reserves the ability to use chemical interventions when absolutely necessary, and instead refers to their approach as “biointensive.”

The hungry birds, vintners say, also often eliminate the need for automated weeders and tractor passes.

Nathan Wood, vineyard manager at Johan Vineyards, a 175-acre estate in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, focuses on biodynamic and regenerative agriculture, both of which prioritize biodiversity writ large as the healthiest and most effective way to combat unwanted pests.

“By having half of our land under vine with many native forest breaks, [it allows] native wildlife, and natural farming systems to interact,” Wood said.

Wood uses 60 chickens to manage the insect population and reduce the presence of boring beetles, plus birds of prey to control rodent populations — his favorite being the Great Blue Herons that hunt vine-munching voles — and 40 sheep to weed and improve soil health.

“We are entering our third year of grazing-based viticulture,” Wood said. “We have seen many benefits on soil health and systems benefits already — a few being decreased tractor use and less compaction. We are looking forward to a few more years of data to start to understand some of the changes in soil organic matter and fruit composition from implementing this approach.”

Other studies support his observations: A 10-year study conducted by University of California Cooperative Extension (UCCE) and UC Davis of vineyard sites in California showed that sheep grazing boosts organic carbon sequestration, microbial biomass, and increases levels of both nitrogen and phosphorous in the soil — key nutrients for healthy grapes and tasty wine.

But like Brock, he agrees that there is no silver bullet when it comes to farming approaches — and that his methods aren’t cheap in the short-term.

“Keeping the vineyard on the edge of natural systems and encouraging interaction helps keep rodents and insect populations living in balance with the system, rather than becoming a dominant problem,” Wood noted. “Though there is a significant cost to these approaches, we feel the cost of destroying our soil and the microbial balance would be even more costly to our planet in the long-term. Hopefully, these decisions will also produce better grapes and better wine.”

Hiring Farm Animals to Do the Heavy Lifting

Other wine-growers are recruiting a variety of animals for tasks around the farm usually designated to machines — often at a significant cost. At the 30-acre Osmote Wine in the Finger Lakes, winemaker Ben Riccardi said he used a team of pigs to help clear a one-acre block he wants to plant.

“They root and clear paths so we can get in there and continue to pull trees,” Riccardi said. “They have helped take a lot of weedy biomass out, and have added a lot of nitrogen to the soil through their waste. The pigs have saved some tractor passes, and the need for a bulldozer or forestry grinder.”

Moraga Vineyards, with seven acres under vine on steep hillsides in Bel Air, California, brought in sheep to clear the land.

“Our steep hillsides don’t allow us to use tractors, so we relied on chemicals or manual brush clearing, which is time-intensive and raises safety concerns,” said Moraga winemaker Paul Warson. “We recently decided to bring in sheep to weed, and we hope that they will improve our soil structure and add nitrogen to the soil, which will also reduce the amount of future inputs we need.”

At Treasury Americas, sheep are also used to weed and reduce their carbon footprint by eliminating tractor passes. The team has also brought in goats and cows.

“All three work together to mitigate risks from wildfires,” Kern said. “Goats and sheep eat their way through flammable brush and debris, and clear the way for removals of more fuel, like dead wood. This creates a shaded fuel break, which mitigates fire risk while maintaining healthy and mature trees. Cows are also grazing the hillsides … to eliminate excess fuel.”

As catastrophic wildfires — 2021’s wildfires in California caused an estimated $70 billion in damage alone — fueled by climate change threaten life and property, more and more state parks, preserves and farms are using goats to mitigate risk.

Horsepower Vineyards in Walla Walla, Washington, meanwhile, uses horses to farm vineyards inhospitable to machinery. Founder Christophe Baron deploys six draft horses across just over 18 acres, on slopes so steep tractors are not an option. Plus, using horses in lieu of tractors means less soil compaction, and erosion reduction.

“People said I was crazy, that I’d break my equipment and waste my time and money.”

“People said I was crazy, that I’d break my equipment and waste my time and money,” Baron recalls. “But I knew that vines need to struggle in poor ground in order to provide their best.”

Using horses, he also knew, was a viable option if the machines most farmers rely on couldn’t hack it. Plus, using horses to farm is a key part of his biodynamic farming philosophy.

For many, beginning to use insects, wild birds, and/or farm animals in the vineyard instead of chemicals and tractors will require, at the very least, a mental adjustment. And while adding insectary rows and bird boxes probably doesn’t require such a huge philosophical shift or a hefty financial outlay, recruiting a herd of sheep to do the weeding or trading horses for a tractor does.

“I could buy a new Ferrari a year for the cost of running these stables,” Baron admitted. “The Ferrari has a horse on it, but that’s not the horse I’m interested in having! We use the horses in the vineyards because it enables us to use high-density plantings. Aside from adding the animal element to the property, by bringing back the horses in the vineyards, we are closing the biodynamic circle.”