Stem cell-derived embryos could make high-quality genetics more accessible than ever — if scientists can finally generate a live birth.

In a lab in Texas, and another in Florida — and in a handful of others throughout the world — researchers are trying to make something happen for the first time in history: a pregnancy without the use of an egg or sperm.

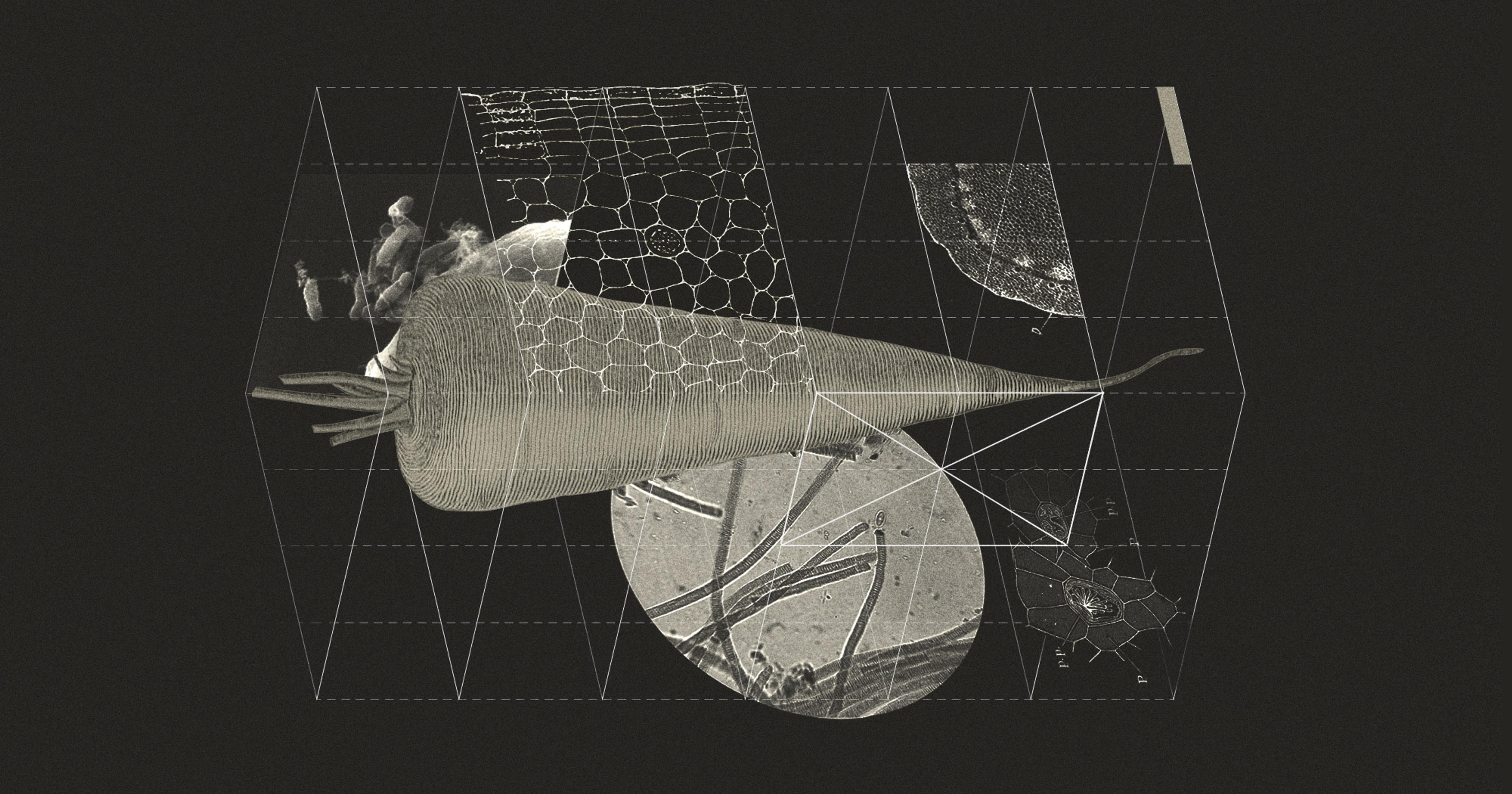

Using stem cells, scientists have grown what are essentially models of blastocysts — an embryo in a stage of development about six to eight days after fertilization. These so-called “blastoids” have a massive research potential, helping scientists to better our understanding of how embryos develop, why pregnancies fail, and the behavior of diseases.

But they also have another practical application that could have a huge impact on the agriculture industry.

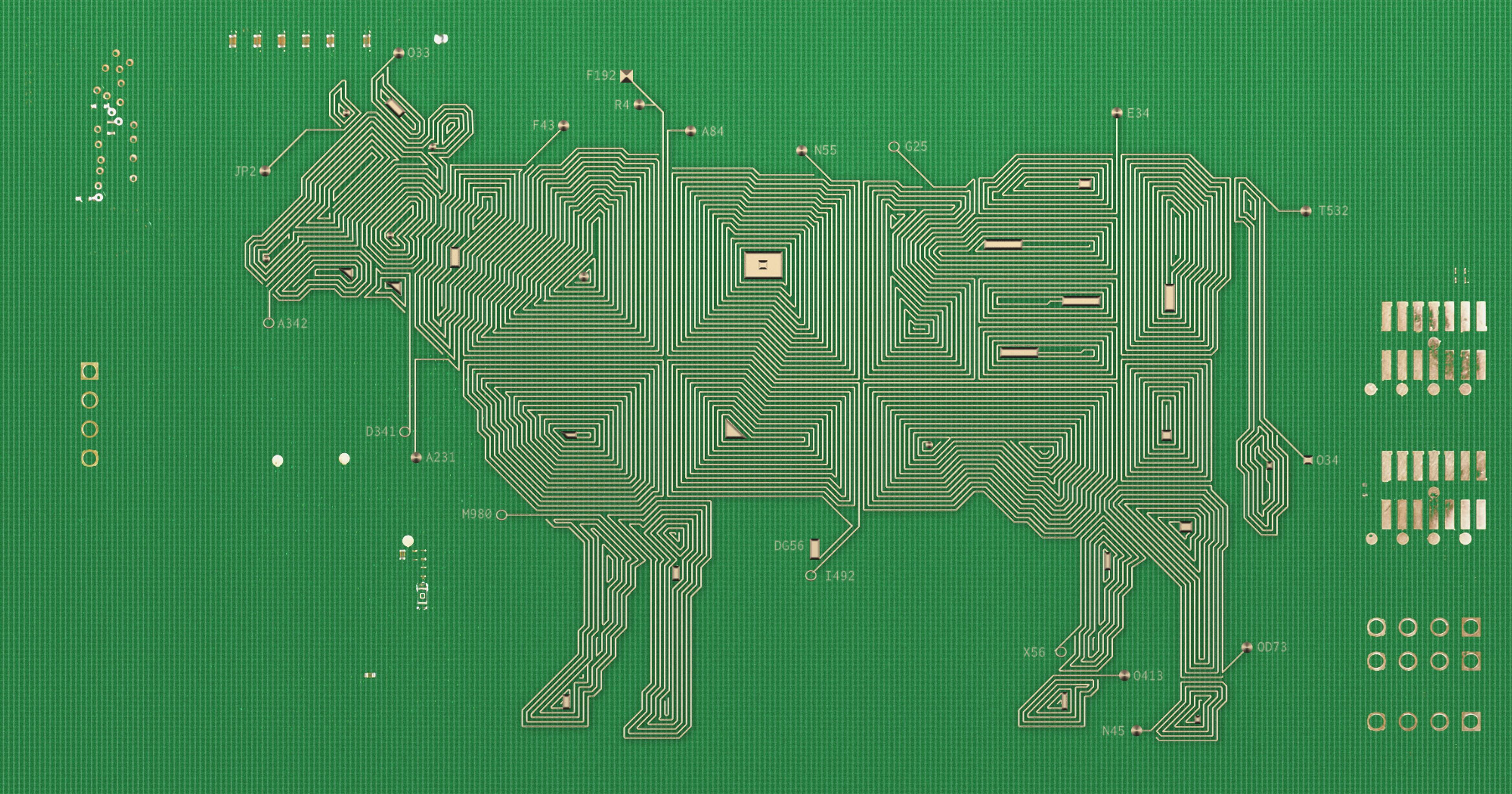

“Think like Star Wars, like the army of clones, but an army of cows,” said Carlos Pinzón-Arteaga, one of the researchers on a team at UT Southwestern Medical Center that published the first “bovine blastoid” recipe in 2023.

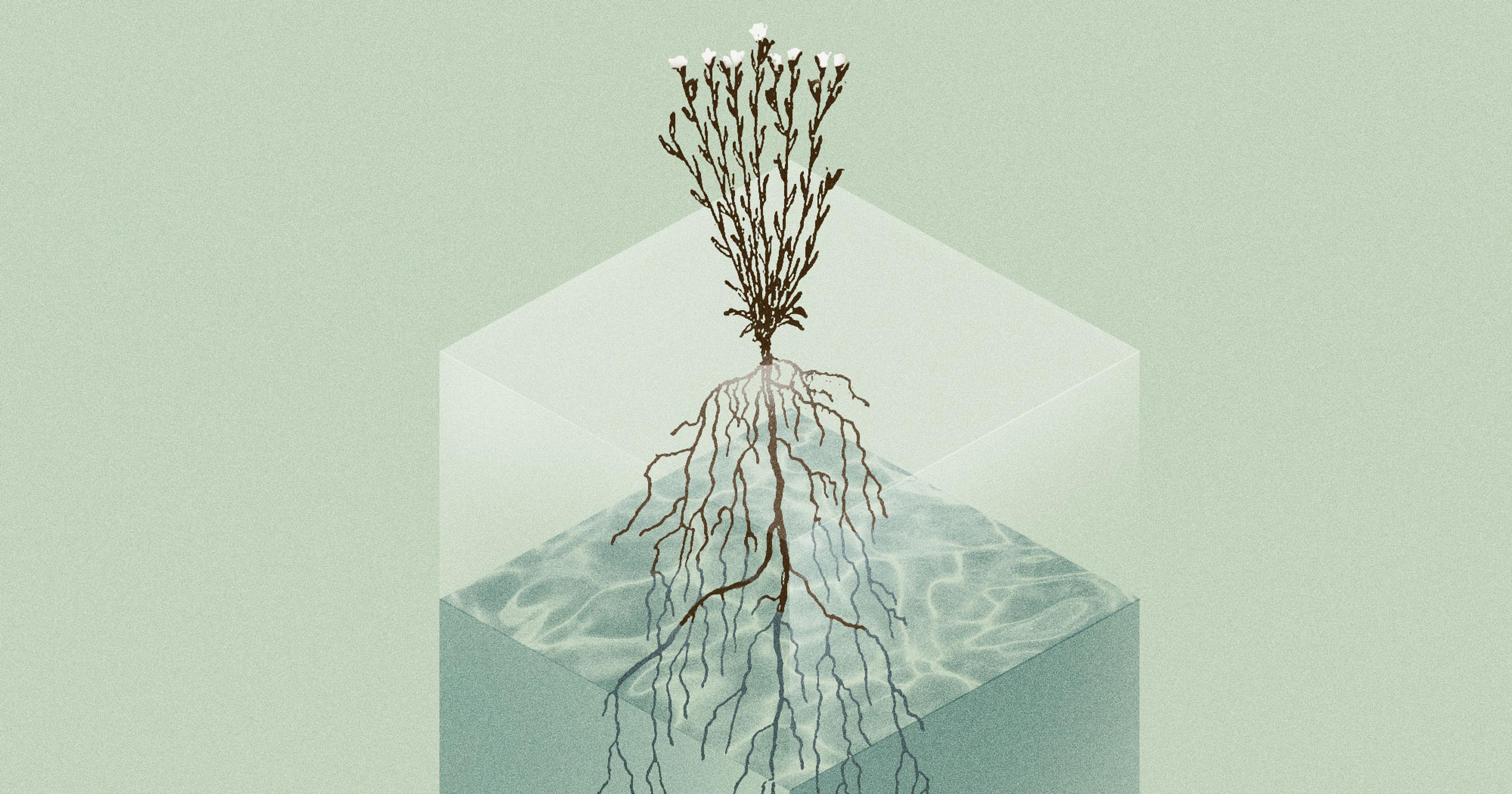

The hope is to impregnate an animal with a synthetic embryo and to deliver a healthy pup. But the problem still beguiling researchers is that so far none of the blastoids have successfully resulted in a pregnancy.

Cows in Florida

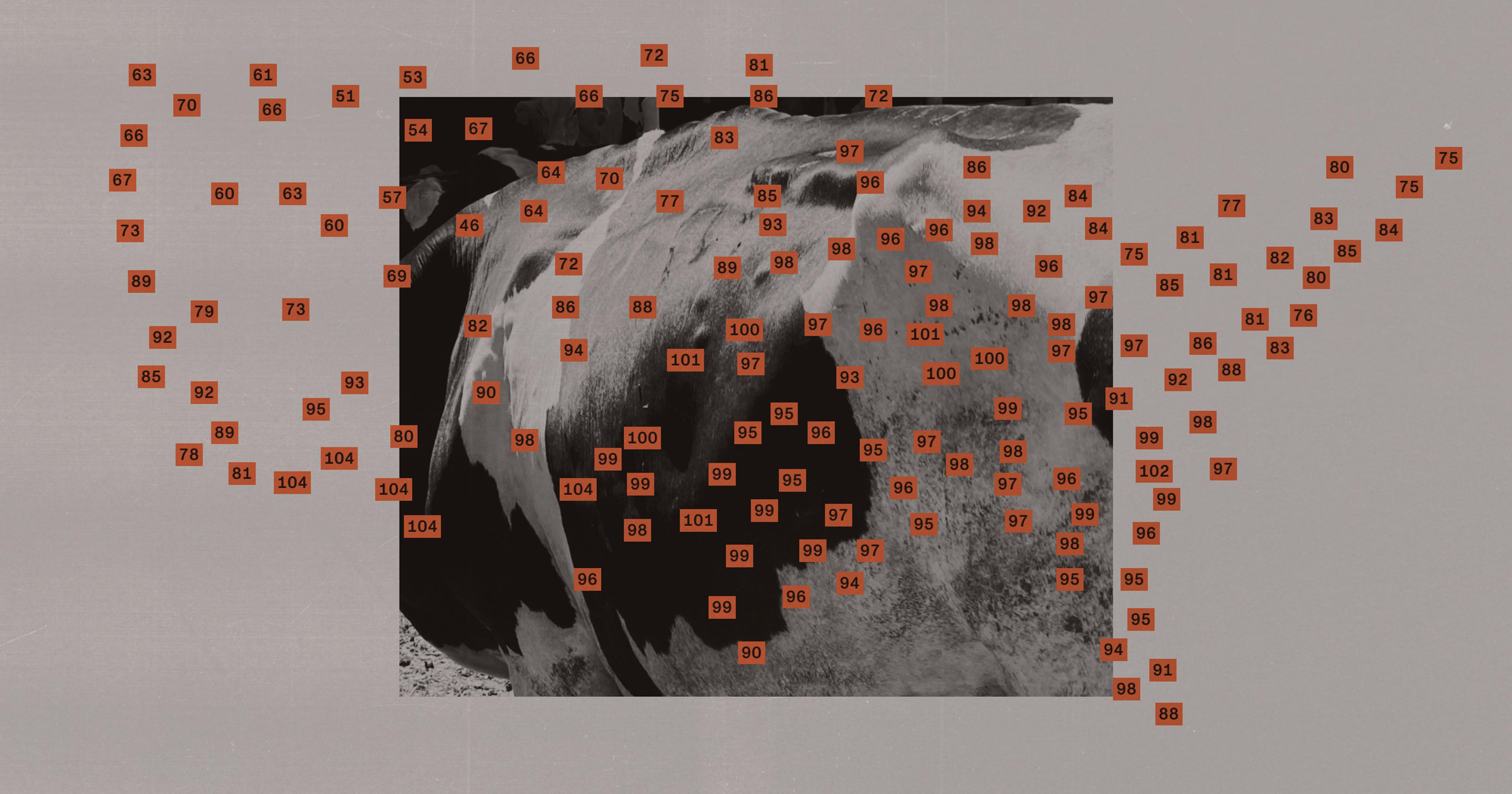

Since 2023, a research team at the University of Florida led by the reproductive biologist Zongliang “Carl” Jiang has been trying out the synthetic embryos in cows. After giving hormones to recipient cows, his team uses catheters to deposit blastoids into the uterus.

After a few days, they flush them out and examine them for signs of development. Jiang hasn’t yet published the results of the most recent trials but early attempts were unsuccessful.

“We’ve never recovered any viable structures,” Pinzón-Arteaga said. “Once they get into the cow, they just die.”

This isn’t altogether surprising. The use of embryonic stem cells from cows is relatively new compared to other animals, and therefore not well understood; the blastoids likely need tweaking if they are going to successfully create a pregnancy. But the potential is massive: A farmer looking to improve their herd’s genetics could pay a company to transfer blastoids derived from the cloned stem cells of, say, a champion heifer.

“Think like Star Wars, like the army of clones, but an army of cows.”

The process would likely be similar to embryo transfer today, which is part of the in-vitro fertilization process, but it wouldn’t require the extraction of eggs from a mother cow. And even more importantly, once you have the blastoid recipe figured out they are easy to make en masse.

“You are not bound by a limited number of embryos,” said Jun Wu, an associate professor in the department of molecular biology at UT Southwestern who collaborated with Jiang to create bovine blastoids. “With stem cells, essentially every week we can produce hundreds of thousands of these.”

Pinzón-Arteaga — who developed an interest in cows growing up in Colombia, where his uncle is a bovine embryo transfer specialist — hopes the technology could level the playing field for farmers who normally lack access to the latest advances in reproductive science.

In places like Latin America or Africa, where livestock is often owned by families dependent on just a few animals, farmers can’t afford to buy a high-producing dairy cow like a Holstein, and because of the cost an embryo is also likely out of reach, he said.

“But if you were able to produce clones from that cow at a very large scale — this is what the blastoid technology can promise,” said Pinzón-Arteaga, who is now a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Medical School. “And then you can really kind of democratize access to high-quality genetics across the globe for the small producer. So that’s the dream of what the technology can achieve.”

‘High risk, high reward’

At his pioneering Texas lab, Wu has cultivated a catalogue of stem cells from a variety of species for research and preservation. His lab’s portfolio includes everything from cows, sheep, pigs, and horses to endangered species like the Northern White Rhino. These days, Wu’s blastoid work is mostly focused on humans and mice — the animal most scientists agree will be the first to give birth through a synthetic embryo, if it happens at all.

Cows present logistical challenges because of their size and the cost of caring for them, and they are also relative newcomers to the stem cell game. Scientists first derived embryonic stem cells from mice in a lab in 1981, but it wasn’t until 2018 that a team of them, including Wu, were able to do so for cows.

Synthetic mouse embryos have even been found to begin growing organs in a lab, with a brain and beating heart starting to develop after just over a week.

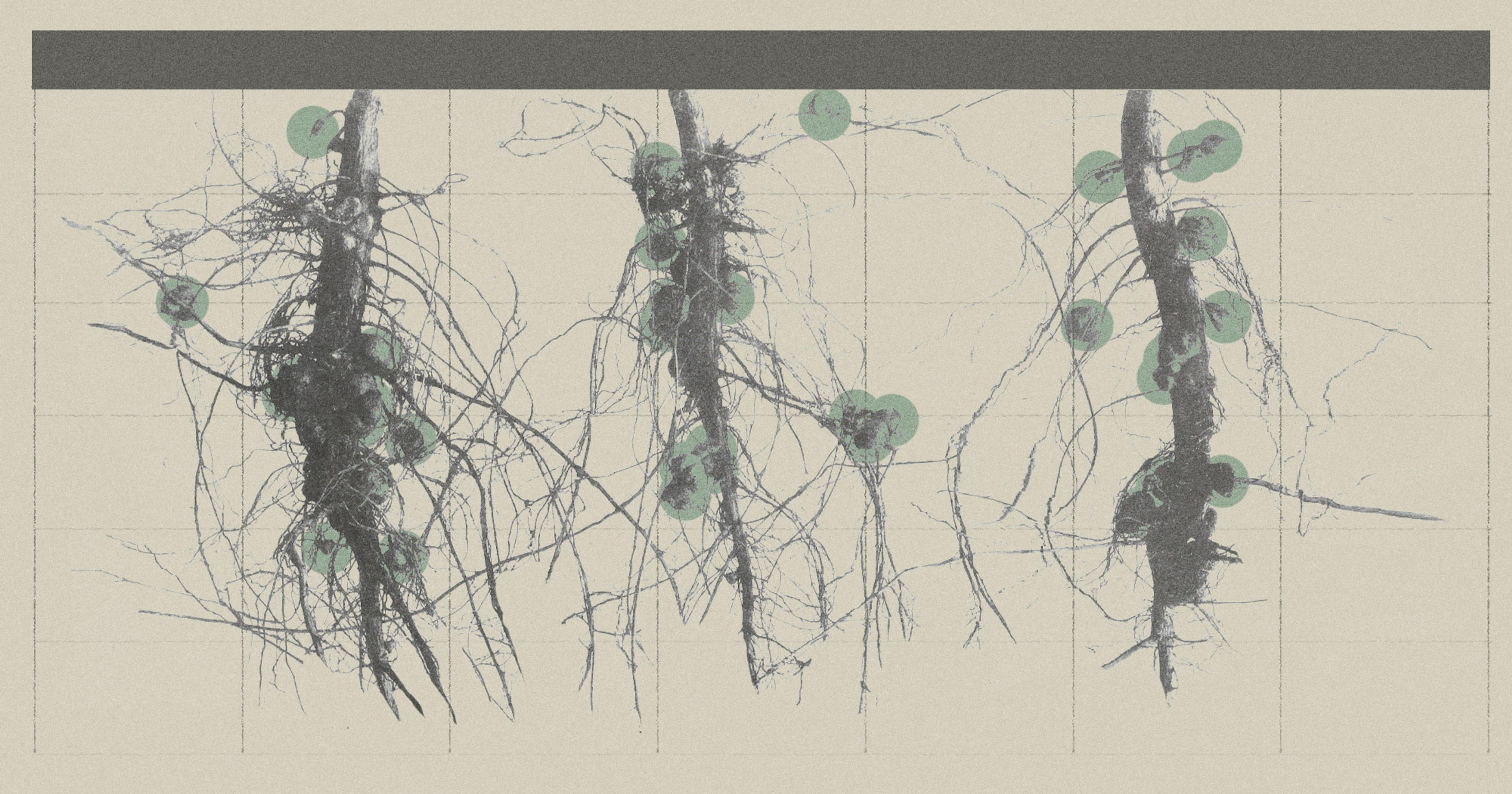

“We need a better [bovine] starting cell and we need better embryonic stem cells like we see in mice and rats,” Jiang said.

In its current experiments, Jiang’s team is trying to understand what happens to the embryos in the initial stages of a pregnancy “because particularly in cattle the majority of pregnancy loss occurs during the first few weeks.”

“Then you can really democratize access to high-quality genetics across the globe for the small producer.”

“If we think these blastoids have the potential for agriculture applications, they are going to need to develop through that critical step after transfer,” he said.

Much of the work is focused on perfecting the blastoid recipe, which consists of cloned embryonic stem cells that are cultured in a cocktail of other inputs. Jiang and his research team have developed a new protocol for bovine blastoids using three different stem cell lines, one more than the previous recipe called for, and he says the end result better resembles a real blastocyst.

But according to Wu, it remains unknown if viable embryos can actually be generated from stem cells, in part because nobody has found a way to induce cells to create a “functional” placenta in a lab. Then there is the fact that embryonic stem cells can undergo changes when placed in culture that may make them unsuitable for creating a pregnancy.

“Even though they came from the egg and sperm, they’ve been cultured in vitro for a long time, and they may have accumulated changes that could be irreversible,” Wu said.

A Global Race

Despite the challenges of working with cows, international industry has shown interest in the research of Jiang and his collaborators, and he said several companies have discussed patenting the original bovine blastoids. The global animal genetics company Genus plc “is currently sponsoring research being conducted by the University of Florida in this space (using stem-cell derived blastoids in animal reproduction),” said Clint Nesbitt, global director of regulatory and external affairs at Genus.

Government funding into this research has been hard to come by, however, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture has turned down all three of Jiang’s grant applications.

“They are very cautious and don’t support this kind of high-risk, high-reward project — which I think they should, but so far I haven’t had luck on that,” Jiang said.

Meanwhile in China, researchers are focusing on pig blastoids with funding support from the government.

“[USDA] are very cautious and don’t support this kind of high-risk, high-reward project — which I think they should.“

“Chinese people love pork,” said Yinjuan Wang, a researcher at China Agricultural University who got her Ph.d under Jiang when he was a professor at Louisiana State University. “Pig, bovine, and ovine are the three important livestock species in China, so the Chinese government will fund lots of special programs for these three species.”

First, though, Wu and others think research into mice will determine if live births from synthetic embryos are possible at all. If they are, the door flings wide open for all sorts of advancements — from species preservation, to disease modeling, to what Pinzón-Arteaga calls “cloning on steroids.” It would also introduce a host of ethical considerations, since there’s no biological reason why the same techniques couldn’t be applied to humans.

With a half dozen labs working on mouse blastoids that Wu is aware of, he is hopeful to see developments in the field this year or next. After that, he speculates focus will turn to a large livestock species because of the agricultural needs.

“For the cow, the potential is still far away, and I don’t know how long it will be,” Wu said. “If we’re optimistic, maybe in five to 10 years. But if we’re pessimistic, we don’t know. It’s still an open question whether we can do it or not.”