A fluke lab discovery could upend our need to import endangered wood — a thriving underground market.

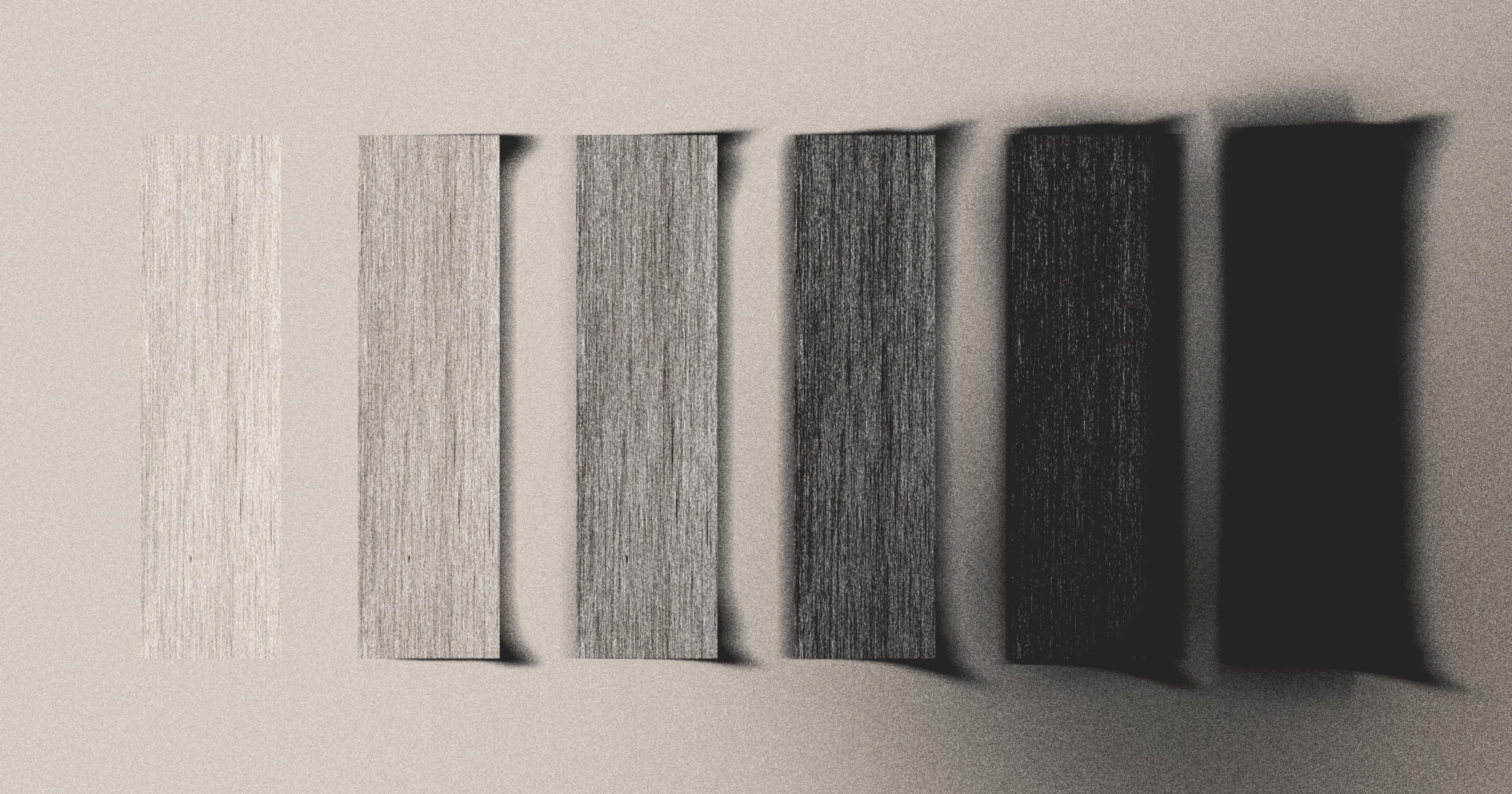

Everything on earth reflects light — a black t-shirt, the feathers of a blackbird, cooled lava rock all bounce light back to our eyes. But there is a scientific quest to find materials that do the opposite, to absorb light rather than reflect it. “Superblack” materials reflect less than 1 percent of light that hits their surface. The current record holder is a polymer that reflects less than 0.0002 percent of light.

Now, among synthetic polymers and chemical paints, a new contender has emerged in the race: a piece of simple carving wood.

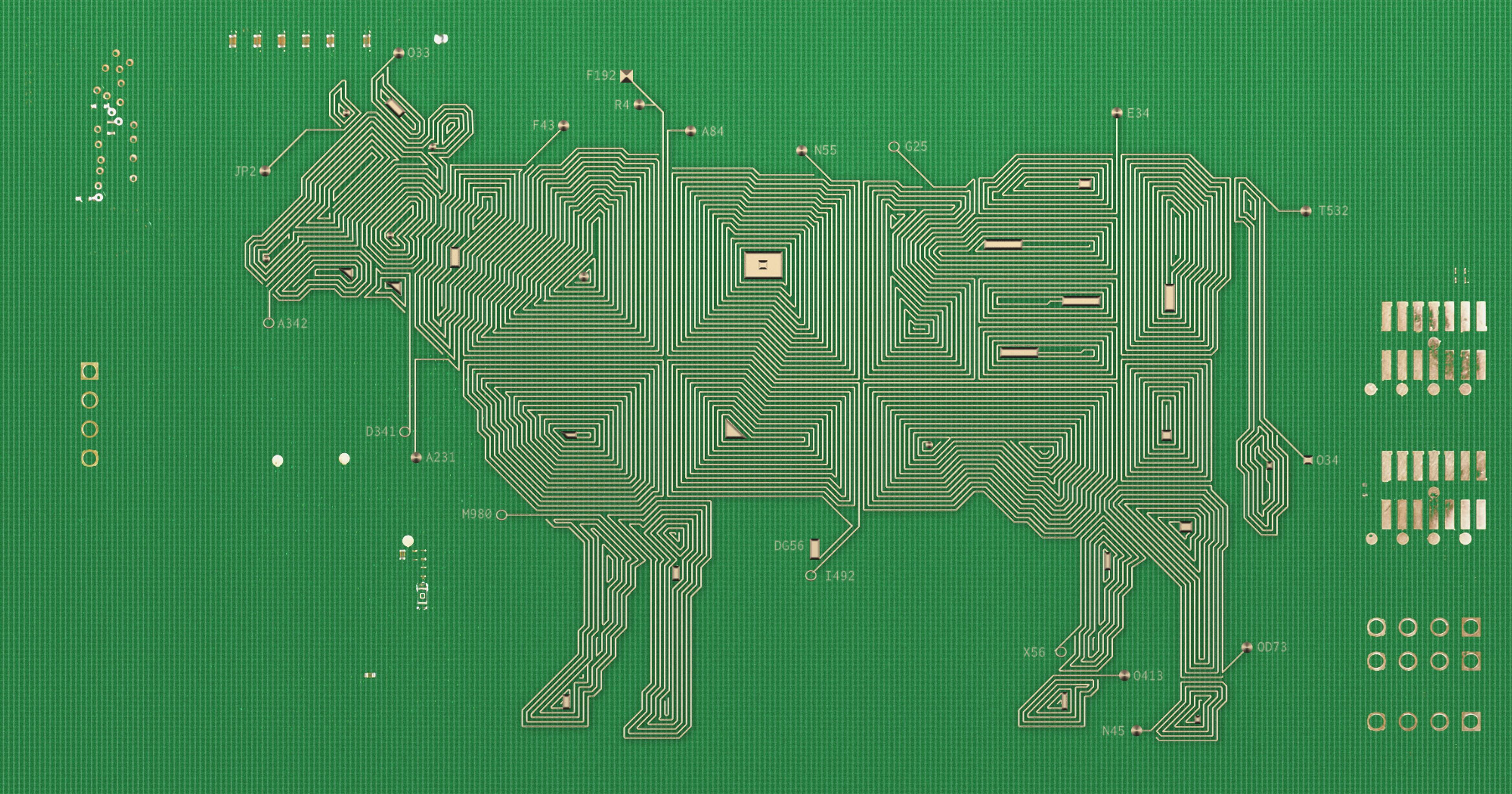

This June, a team of scientists in Canada released the results of a study, wherein they placed a piece of common basswood inside a plasma reactor the wrong way up. It emerged from the reactor as the first wood material to achieve superblack status.

The simple flip of a wood sample, from its longitudinal edge to the transverse, showed that a common, light-colored wood could mimic — and surpass — the velvety color of dark hardwoods coveted for furniture, musical instruments, and art.

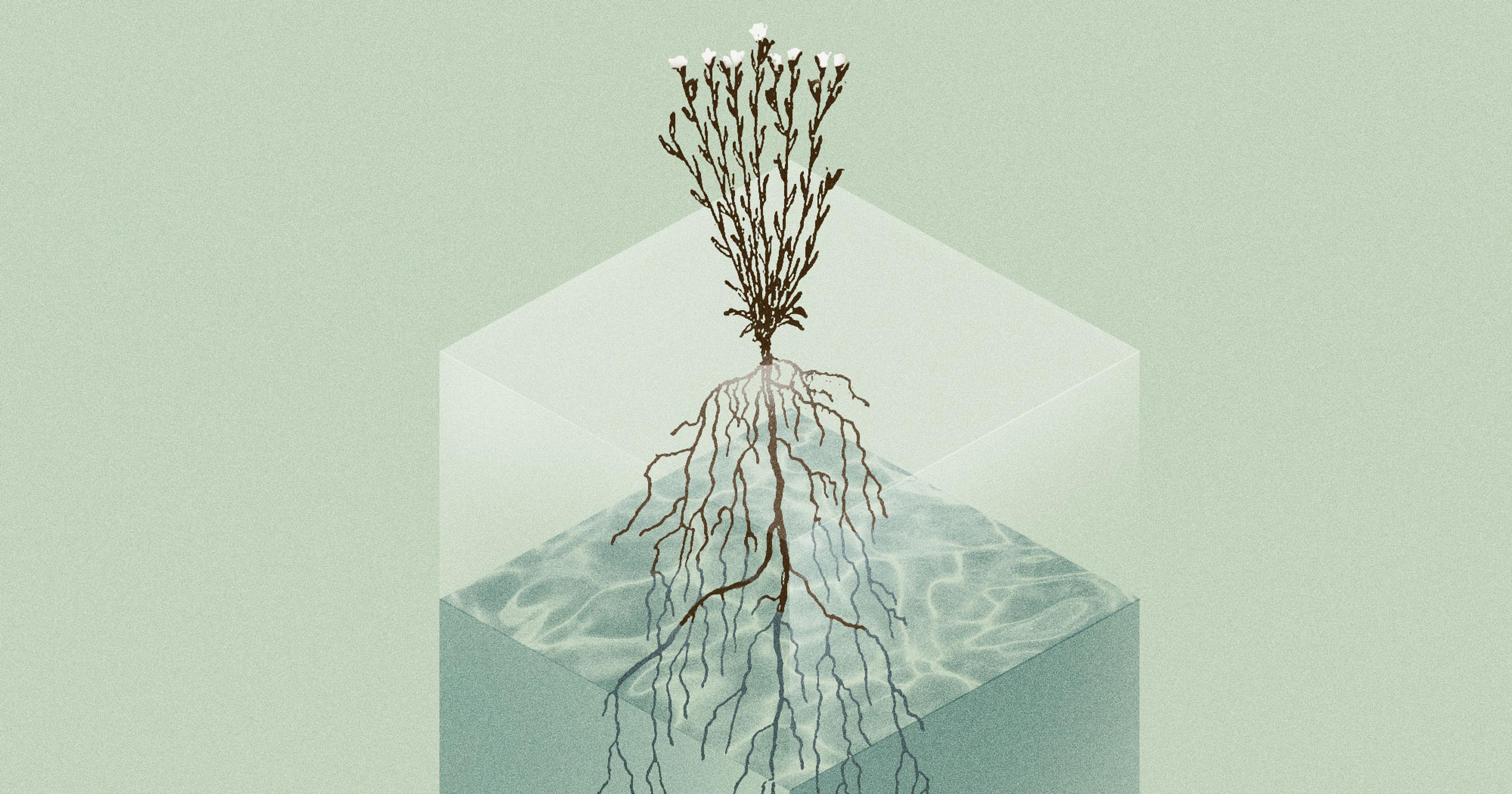

The scientific discovery now raises the possibility of using plasma to create substitutes to precious — and endangered — centuries-old darkwoods. The hope is to help stymie the illegal logging of wood, which ranks as the third most lucrative transnational crime behind drug trafficking.

“You’re never going to stop the trade unless you can develop a substitute material that is just as good,” said Philip Evans, senior author on the study and professor of forestry at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Dark Matter

Plasma is often referred to as the fourth stage of matter. Energy melts a solid ice cube into water, and boils water into gas. When gas is heated by more energy, the molecules rip apart, forming a soup of positively charged ions and electrons. This ionized soup, called plasma, appears in our skies as the Northern Lights or streaks of lightning bolts.

In the 1970s, at the start of Evans’ career, plasma emerged as a way to change the surface of wood.

Waxy woods like eucalyptus, when placed within a plasma reactor for a few seconds, become wettable, meaning that glues could spread and stick to the wood surface, making eucalyptus furniture a possibility. By 2018, Evans began to use plasma on wood in the same way that semiconductor manufacturers etched grooves and pathways into wafers of silicon.

A metal plate protected some of the wood within the reactor, leaving the exposed wood to get etched away. Evans and his doctoral student Kenneth Cheng bombarded the longitudinal side of the wood, the direction that the water flows within tree trunks, with plasma.

Instead of the golden color they saw on the long edge, the transverse wood sections emerged from the plasma reactor black.

But, for completeness, Evans asked Cheng to run the tests again on the transverse edge of the wood, the weaker side of the wood that emerges when you chop down a tree. Transverse wood cuts are typically seen atop decorative end tables or kitchen cutting boards.

Instead of the golden color they saw on the long edge, the transverse wood sections emerged from the plasma reactor black — very black, so black that Evans asked a team of astrophysicists to measure the reflectivity of the surface.

But appearing black to the eye does not equate to reflectivity. Many dark materials still reflect light in other wavelengths outside the visual range, said Luke Schmidt, who tested the plasma-wood samples for Evans at Texas A&M University. The plasma-etched wood, to Schmidt’s surprise, reflected only 0.68 percent of light across the visual and ultraviolet wavelengths.

It was superblack.

Illegal Harvest

The wood may have started in the lab, but the superblack wood’s size and shape leaves it without an obvious “home run application” for science, Schmidt said. Synthetic polymers or paints made from tiny tubes of carbon can more readily spray the inside of telescopes and other scientific equipment — one of the most common current uses for superblack.

More likely, Evans said, the superblack wood could relieve pressure on the precious darkwood industry, where centuries-old trees are felled for consumer goods like furniture bound for Asian countries or musical instruments bought in the West.

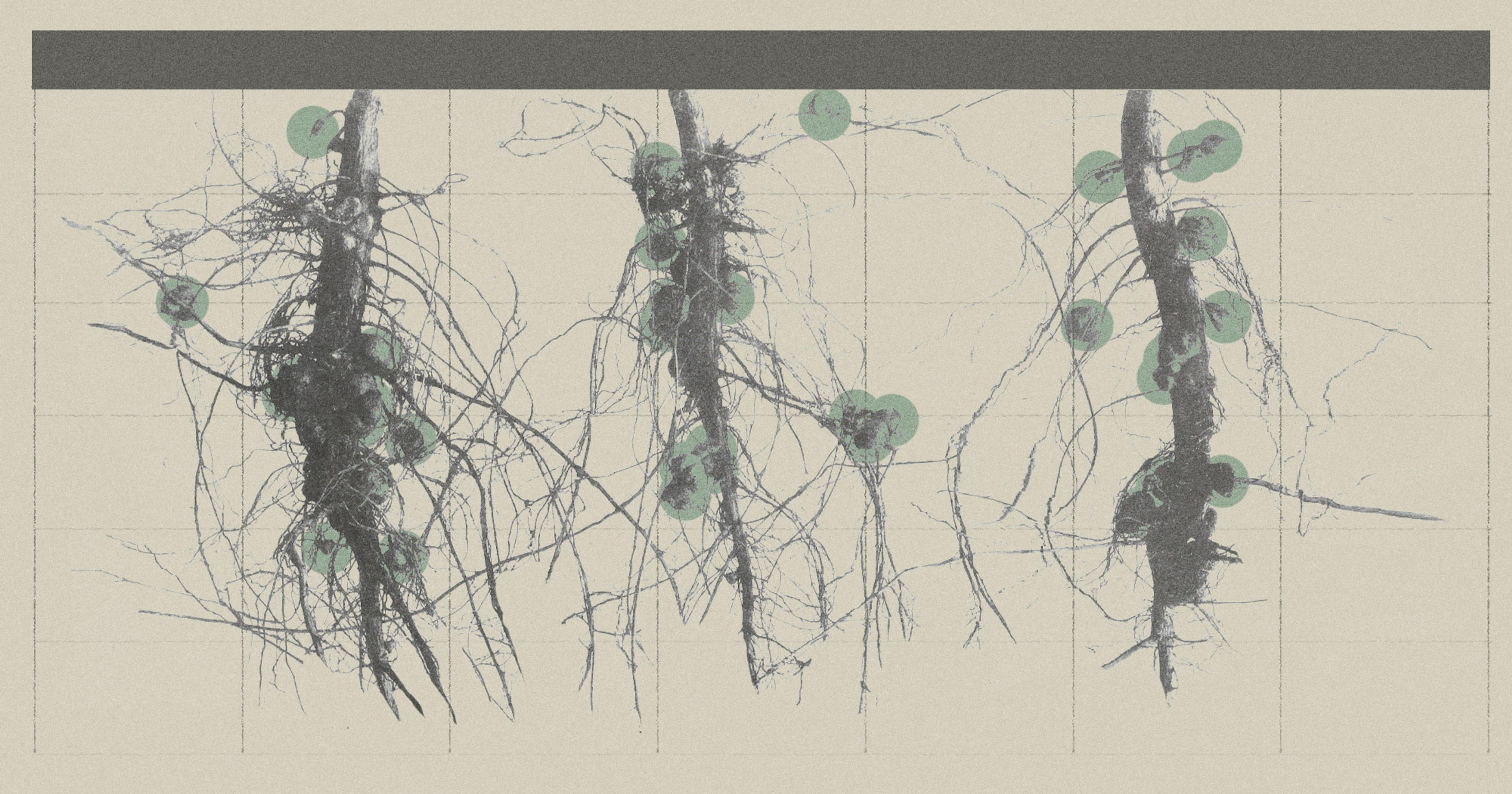

Overharvesting has landed many dark and tonewoods on the CITES Illegal Trade Database, a list of endangered flora and fauna that the international community has agreed to not trade or trade only in very particular circumstances.

The plasma-etched basswood from Evans’ lab looks similar to ebony, a precious wood used in guitar fretboards because of its dark color and durable hardness. But only one in 10 ebony trees are pure black; the other nine are streaked with an undesirable white color — and discarded, a wasteful end to their centuries-long life.

Anything to divert the waste of the ebony trade and “give trees a fighting chance of surviving” is “wonderful,” said Edgard Espinoza, the criminalistic section chief of the National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Lab in Ashland, Oregon. There, he and 25 researchers test wildlife samples to determine if the item is or isn’t legal to trade.

But Espinoza has seen how lookalikes to precious natural materials like ivory create more demand for the original item, not less. “People see the fake and they go, man, I’d love to have the real thing, because the fake is so cool, the real probably is better.”

“You’re never going to stop the trade unless you can develop a substitute material that is just as good.”

Only once, in the decades of testing wood samples, did Espinoza come across an inferior wood masquerading as harder, higher-quality species. The wood came from Hong Kong and the importer claimed it was cherry wood. It was compacted so it was hard as cherry, it was dyed to look like cherry, but the spectrometer said otherwise — the molecular signatures did not match the cherry wood spectra. Nor did the signature match any other protected species.

The economics of illegal logging still governs the industry of wood, Espinoza said. Inexpensive timber from Africa — or inexpensive labor in Papua New Guinea or Malay islands — provides wood that sells for “outrageous prices in other parts of the world — that’s what’s the driving force, right?”

In 2012, Gibson Guitar Company admitted to illegally purchasing ebony wood from Madagascar following the ban of its export after 2006. The Gibson case pushed the music industry to more closely monitor its lumber sources, said David Gehl, senior manager of traceability and technologies at the Environmental Investigation Agency, the non-profit that exposed the Gibson’s illegal imports.

Paying for Cool

For now, Evans and his colleagues are focused on fine jewelry — not scientific — applications. “Unfortunately, the world we live in, people are willing to pay for cool, they’re not willing to pay for science,” he said. “The general public couldn’t care less about the papers.”

They’ve created watches with eye-catchingly dark black faces, similar to the Swiss watch company Chronotechna, which coats their watch faces with superblack paint developed at Harvard University. And just as the jewelry store Tiffany sells onyx rings, Evans created rings sporting the plasma-etched wood. The vertically aligned lignin structures at the surface of the wood also make it hydrophobic, Evans found, increasing its prospective value. Since the paper came out, they’ve continued to prototype products, including phone cases.

The plasma-etched wood is now trademarked under the name Nxylon, after the Greek goddess of the night Nyx, and xylon, the Greek word for wood. The Nxylon surface is delicate, Evans said. But they came up with a way of preserving the superblackness and protecting the surface with a thin coating of gold/vanadium. Evans said he has no intention of profiting from the discovery.

“Unfortunately, the world we live in, people are willing to pay for cool, they’re not willing to pay for science.”

It’s difficult to quantify the impact consumer aesthetic preferences have on the illegal logging market, Gehl said. But he wouldn’t minimize it. After the Gibson case, guitar manufacturers claimed that they used too little of the wood to drive the loss of endangered species.

“But I think, you know, overall, all of these industries do really have an impact.” Gehl said.

No matter what its ultimate impact, the plasma-etched wood is a “very valuable development and part of a positive trend of this environmentally-friendly methods and techniques for creating good alternatives to much more destructive and unsustainable products,” Gehl said.