AI-powered robots are very effective alternatives to herbicides. but the costs remain prohibitively expensive.

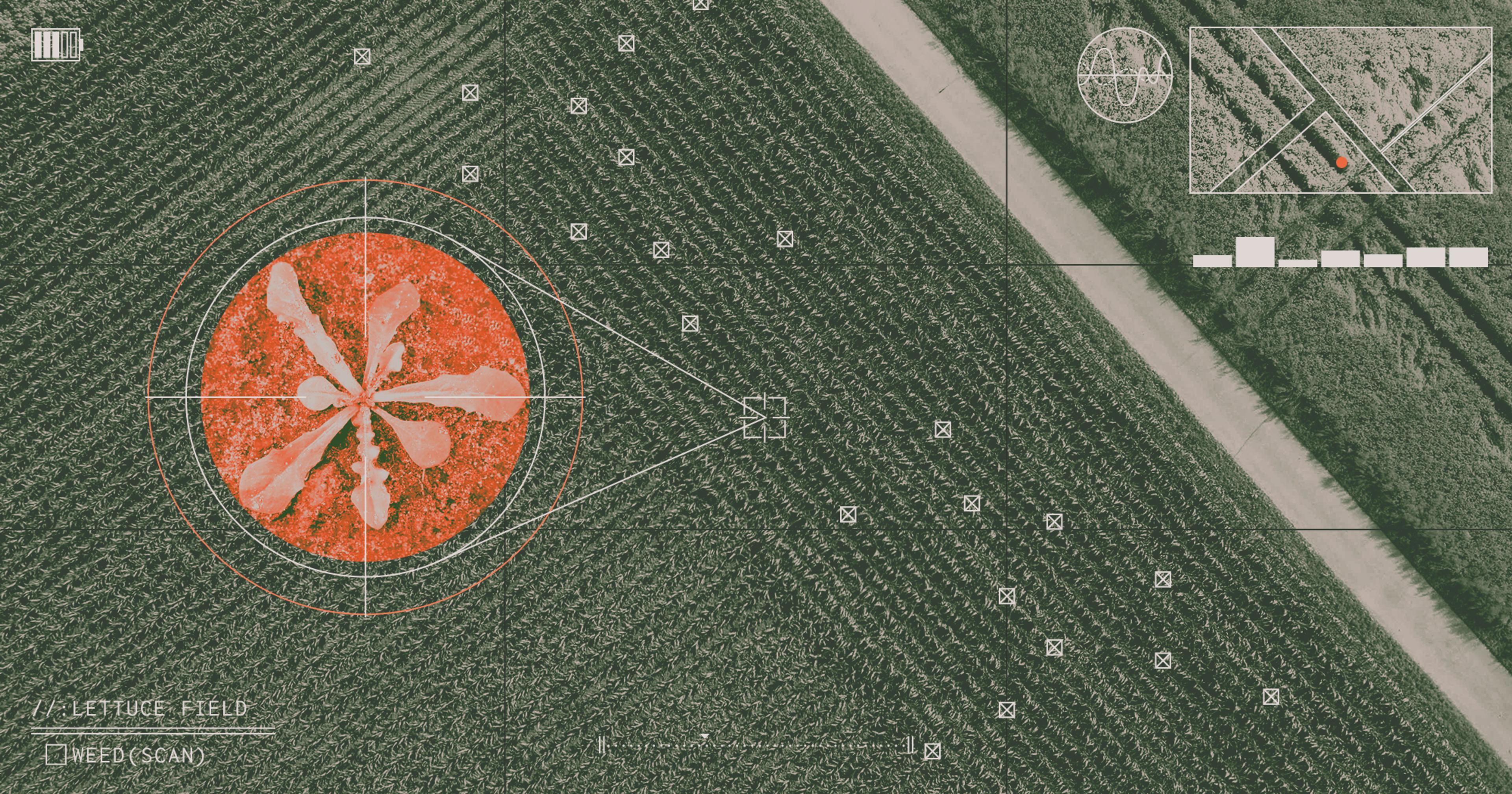

On a warm day in early August, Sean Iliff pressed a few buttons on an iPad and waited for the laser jets to warm up. Before him was a boxy white machine about 20 feet wide, hitched to a tractor and perched over a field of lettuce — one of the key crops grown in the town of Hollister, an agriculture hub on California’s central coast. Iliff, who works for a company called Carbon Robotics, was there to demonstrate the new device before a crowd of curious farmers, researchers, and agtech experts. They craned their necks as beams of infrared light, invisible to the human eye, shot out of the bottom of the machine, hitting the soil with an audible sizzle.

If the field had contained weeds — the laser’s intended target — they would have been burned to a crisp. But a farmer wouldn’t have to do much besides operate the tractor that pulls it, because the LaserWeeder, which claims it can cover two acres and kill up to 300,000 weeds per hour, decides where to fire its lasers using artificial intelligence, or AI. Designed by a team of engineers in Washington state, it’s been trained to recognize weeds from crops, and to shoot the beam at the weed’s meristem, killing it close to the root.

“Other machines have to be programmed to fit the crop that they’re in,” Iliff said. “This machine learns on its own.”

The LaserWeeder may be the only one of its kind on the market, but it’s part of a wave of technology companies using AI and robotics to help farmers deal with weeds. From mechanical arms that pluck the pesky plants out by their roots to drones that spray herbicides directly onto their targets while avoiding crops, these devices are already starting to replace expensive and difficult-to-find human labor. And those that allow farmers to avoid using chemicals hold particular promise for organic agriculture, where weeds threaten to compete with and ultimately damage produce.

“[Farmers are] much more vulnerable in organic systems than they are in conventional,” said Steven Fennimore, a weed ecophysiologist at the University of California, Davis. “So the potential for automated technology to benefit is vastly more important for organic, because they have so little pesticide protection from weeds in any way.”

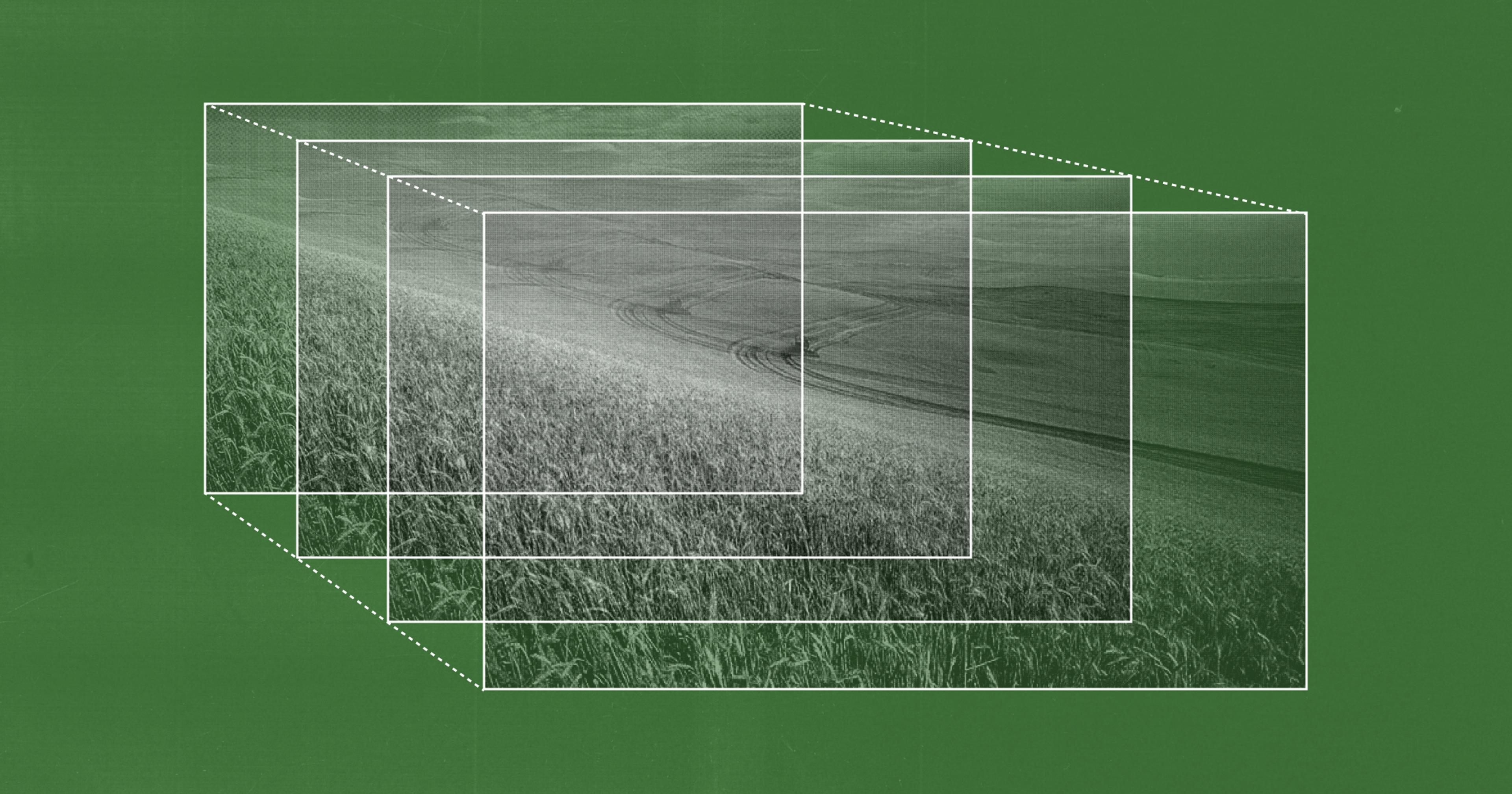

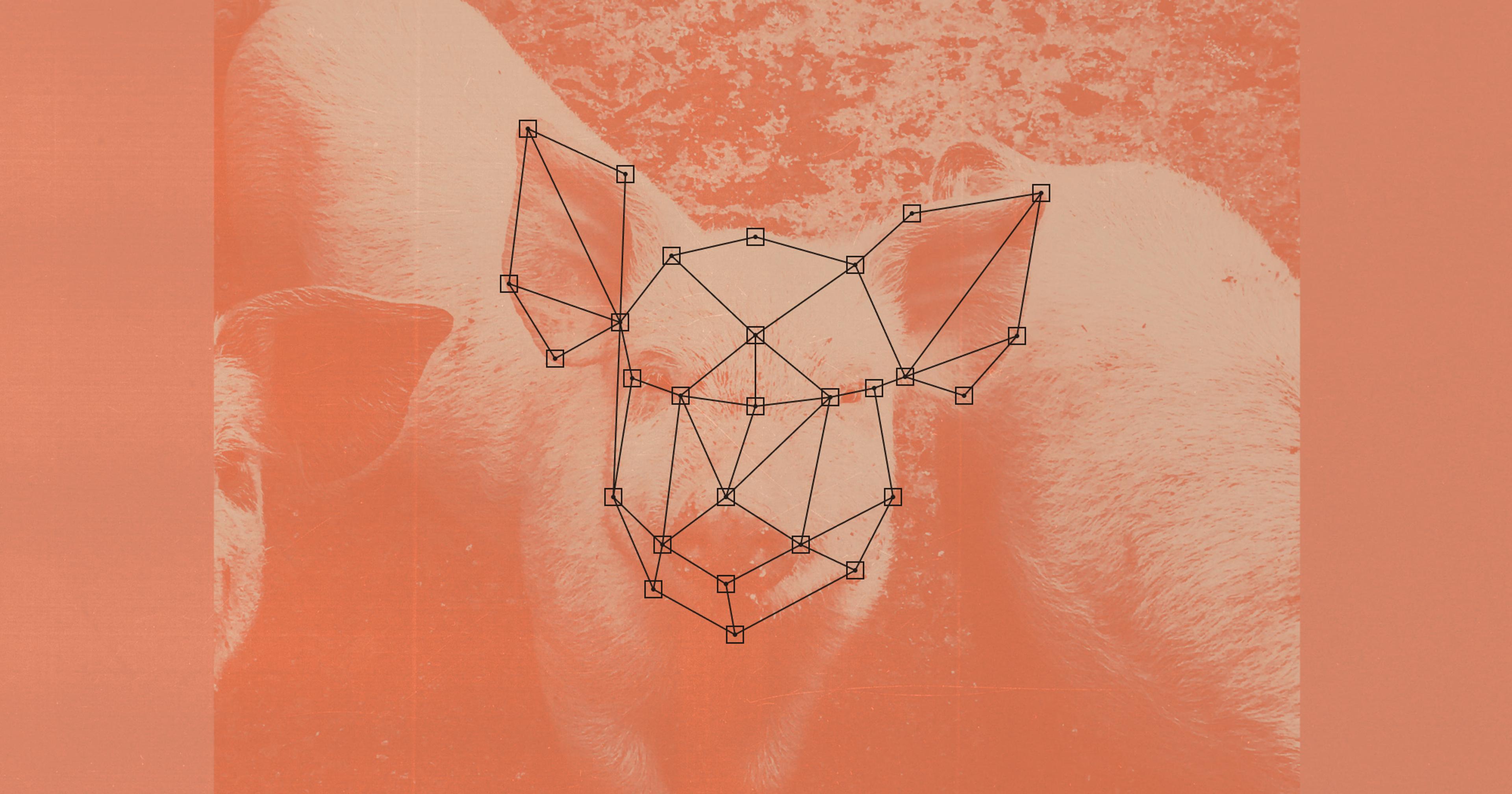

Agricultural AI isn’t limited to weeding, of course. In 2021, 87 percent of agricultural operations in the U.S. reported using some form of AI to manage their farms, according to Relx, an analytics company. Meanwhile, market research placed the value of the U.S. agricultural AI market at $1.63 billion in 2022 and predicts it will reach $7.97 billion by 2030. AI services can help farmers decide what to plant and when to plant it, making predictions based on satellite images, soil health measurements, and weather data; others take the form of chatbots, similar to OpenAI’s ChatGPT, which farmers can turn to with questions about the health of their livestock or how much fertilizer to use. But these virtual assistants have received pushback from farmers who say they can give inaccurate or misleading answers; researchers have suggested that AI models in agriculture need “thorough monitoring and testing” before they are widely implemented.

AI-powered robots, on the other hand, are having much more success tackling repetitive, physical tasks like planting, spraying chemicals, and especially weeding. The technology got its start more than 10 years ago in Europe, Fennimore said, where farmers dealt with more acute labor shortages than in the U.S.. In response, companies like ecoRobotix, based in Switzerland, developed innovations like a fully automated, solar-powered robot that sprays herbicides more efficiently, claiming it can reduce chemical use by 95 percent. Other kinds of precision sprayers, like John Deere’s “See & Spray” system also reduce herbicide use; rather than replacing human laborers, they help overburdened farmers to keep costs down and adapt to increasingly stringent pesticide regulations, Fennimore said.

“The potential for automated technology is vastly more important for organic, because they have so little pesticide protection from weeds in any way.”

Chemical-free robotic AI weeders have taken longer to hit the market, but they’re now proliferating throughout the U.S., where shifting demographics and restrictive immigration policies — along with low pay and difficult working conditions — have led to a severe labor shortage, with less than half of fruit and vegetable growers reporting access to adequate labor in 2023. Carbon Robotics has distributed more than 100 LaserWeeders around the country; though the company wouldn’t disclose its prices, farmers have said the upfront cost hovers around $1 million. Those who can afford it, though, say the benefits are clear. Sabor Farms, a 3,000-acre operation in Salinas, California, finds it particularly useful for leafy greens that face significant threats from weeds, especially when grown without chemical inputs, said farm manager Pete Anecito.

“When we’re talking about high-density planting, the entire bed top is planted, and so trying to get any sort of mechanical weeding mechanism in there has not been possible up until now,” Anecito said. “It’s all been by hand. So we’ve been able to cut down on that hand labor significantly.”

Other AI-powered devices on the market are trying to replace human labor for other needs farmers might have, like monitoring crop counts and soil health. Aigen, which is also headquartered in Washington state, created a solar-powered, autonomous robot that continuously roams around a farm, plucking weeds while gathering data on irrigation levels and the presence of insects. The robot — which founder Kenny Lee called a “Roomba for the farm” — can cover about 40 acres in a growing season. The company deployed around 50 devices this year on sugar beet fields in North Dakota and Minnesota, and is targeting large soybean operations next. Its goal, Lee said, is to center farmers’ needs first by creating a device that helps make their business more financially sustainable in the long run.

“It sleeps on the farm and wakes up on the farm,” Lee said. “If you were to have eyes and ears on the farm at all times, what would you ask it to do?”

“If you were to have eyes and ears on the farm at all times, what would you ask it to do?”

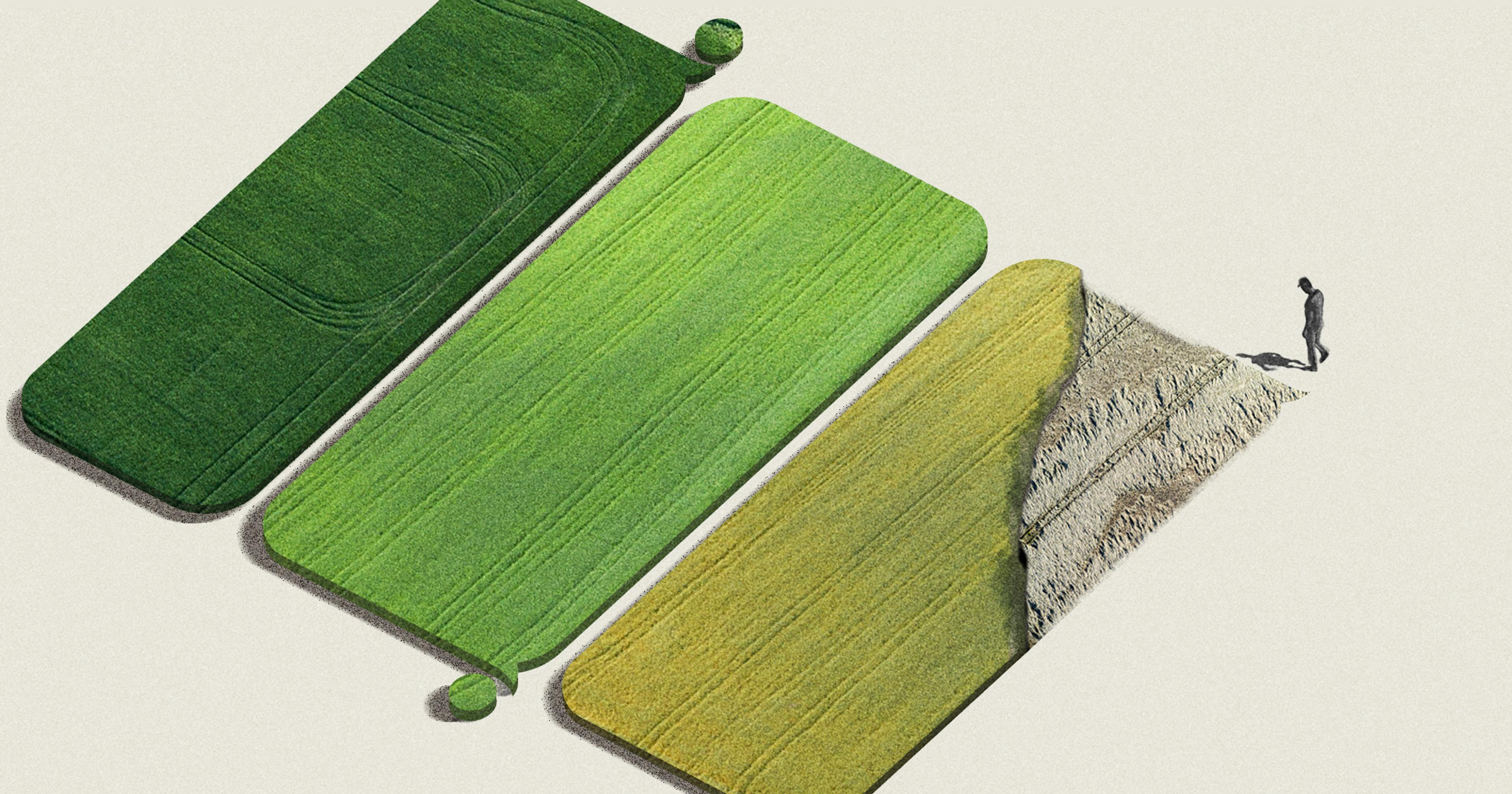

Though the promise of AI for agriculture is great — especially in the organic industry — its applications have been limited so far, said Eric Gallandt, professor of weed ecology and management at the University of Maine. Most of the AI robot weeders on the market today are designed for large farms spanning thousands of acres, Gallandt said, while the needs of small organic farmers — who manage much fewer acres and aren’t able to afford large, expensive machines — aren’t yet being considered.

Adapting the technology to work on smaller farms will come with its own challenges, Gallandt added. The terrain can have more irregularities, creating obstacles for robots that are used to moving across flat ground. Weeds can also be clustered more densely, overwhelming the machines if they’re not built to keep up. But the potential benefits are exponentially greater, with small organic farmers facing existential threats from labor shortages as well as climate change.

Right now, there are few signs that agricultural AI startups intend to consult with smaller farmers and design products around their needs, a “bottom-up” approach that Gallandt supports. But the few devices already on the market show what can be possible; one farmer he knows has been using a KULT Kress weeder, which isn’t fully autonomous but comes with a camera and can replace a crew of four human laborers at what he estimates is a fraction of the cost of the Carbon Robotics LaserWeeder. Even cheaper robots, like the $150 Tertill, have very simple sensors that differentiate crops from weeds by their size. It’s not particularly useful in its current form, Gallandt said, but demonstrates just how accessible these devices can someday be.

“The increasing pressure of labor and climate are going to really motivate farmers to look carefully at any automation that comes along that seems like it’s designed for their farming systems,” Gallandt said. “They watch the very cool YouTube videos of these giant fields in California, and they don’t look at that technology as anything close for them yet, but I think they realize it’s coming.”