For some farmers, combining solar power and agriculture can strengthen both.

When Illinois corn and soybean farmer Mike Wishall first started looking into the idea of installing solar on his land more than eight years ago, he wasn’t sure if it was worth the hype. Working on about three thousand acres, Wishall was interested in generating enough energy to power his operation, but wasn’t totally convinced he’d be paid back for his investment.

But after visiting the one person in his area at the time who had an array on her land and finding that she “couldn’t say enough good about it,” he decided to take the risk and start with one small solar installation on his property. “The first one we put in was in the summertime, and the next power bill, we bought zero power from the utility. We actually sold power back to them,” he said.

“The first one we put in was in the summertime, and the next power bill, we bought zero power from the utility.”

He went on to add two more small systems over the next two years. Today, Wishall’s solar installations generate 90% of the power he uses on the farm each year. Despite his initial hesitancy, he’s become so convinced that solar is a winning proposition for farmers that he now represents the solar company he bought his systems from to his neighbors. “I had a problem figuring out if solar was actually going to be a good deal at the start,” he said, explaining he’d been skeptical of claims from solar companies. “But it did work; the incentives are real. The systems will basically pay for themselves.”

Wishall is one of a growing number of farmers across the United States who are integrating solar and agriculture. Research from Cornell found that in New York, 40% of current solar energy capacity has been developed on farmland, and 84% of land considered suitable for future solar development is also farmland. Though there’s a lack of solid data tracking those numbers across the rest of the country, there’s reason to believe the New York study may be indicative of a wider trend.

“It did work; the incentives are real. The systems will basically pay for themselves.”

“Solar developers are looking for lands that are flat and cleared of vegetation, reasonably close to roads and close to power infrastructure,” explained Dr. K. Max Zhang, a professor in the Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Cornell who researches the nexus of solar and agriculture. “Farmland fits all those criteria.”

Solar can be financially enticing for farmers, too. Some, like Wishall, may look to small systems to gain energy independence and lower their power bills. Others may sell or lease larger field-sized plots of land to solar developers as an additional revenue stream. According to Joel Tatum, the Midwest solar specialist at American Farmland Trust, a non-profit dedicated to protecting farmland, farmers can make “substantially more” per acre on solar than they are making on crops, “with zero input and zero labor attached.”

“Say the farmer doesn’t have a next generation that’s going to take over the land, and the farm ultimately would be for sale. The solar path is very attractive,” he said. But while American Farmland Trust doesn’t want to “negate that opportunity for the farmer,” the organization also doesn’t want to see all the country’s prime farmland diverted away from growing food, either — so Tatum and his colleagues are dedicated to helping people find a way to incorporate solar without giving up agriculture.

One of the simplest ways to balance the two is to follow Wishall’s example and install solar in spaces where agricultural production isn’t currently taking place, whether that’s marginal land or a barn roof.

This is the kind of system that Straight Up Solar, a solar energy design and installation company that services Missouri and Illinois, most frequently installs on agricultural properties. According to Straight Up’s VP of development Shannon Fulton, the area’s geology allows solar panel mounts to be driven directly into the ground without concrete, subsurface pilings, or any additional support. That’s a boon, she says, because it means solar panels can be more easily decommissioned at the end of their 25-30 year lifespan.

“From an agricultural perspective that’s great,” she said, “because at some point, if you want to reclaim the land for growing food or whatever else, that should be fairly simple to do.”

“If you want to reclaim the land for growing food or whatever else, that should be fairly simple to do.”

Tatum also finds himself increasingly advocating for and trying to educate farmers about agrivoltaics. In agrivoltaic systems, solar and agriculture are combined on one plot of land — think crops growing beneath elevated solar panels.

Thomas Hickey is currently researching agrivoltaics both as a graduate student at Colorado State University and as the R&D lead at Sandbox Solar, a solar company based in Fort Collins, Colorado. Like Tatum, he sees the benefits of agrivoltaics as a partial solution to the problem of competition for land. Much of the land that solar companies would consider “low-hanging fruit” has already been developed, he notes, and developers are increasingly looking to agricultural land for expansion.

But agrivoltaics provides other benefits beyond minimizing land competition, Hickey says: combining agriculture and solar can actually benefit the operations of both.

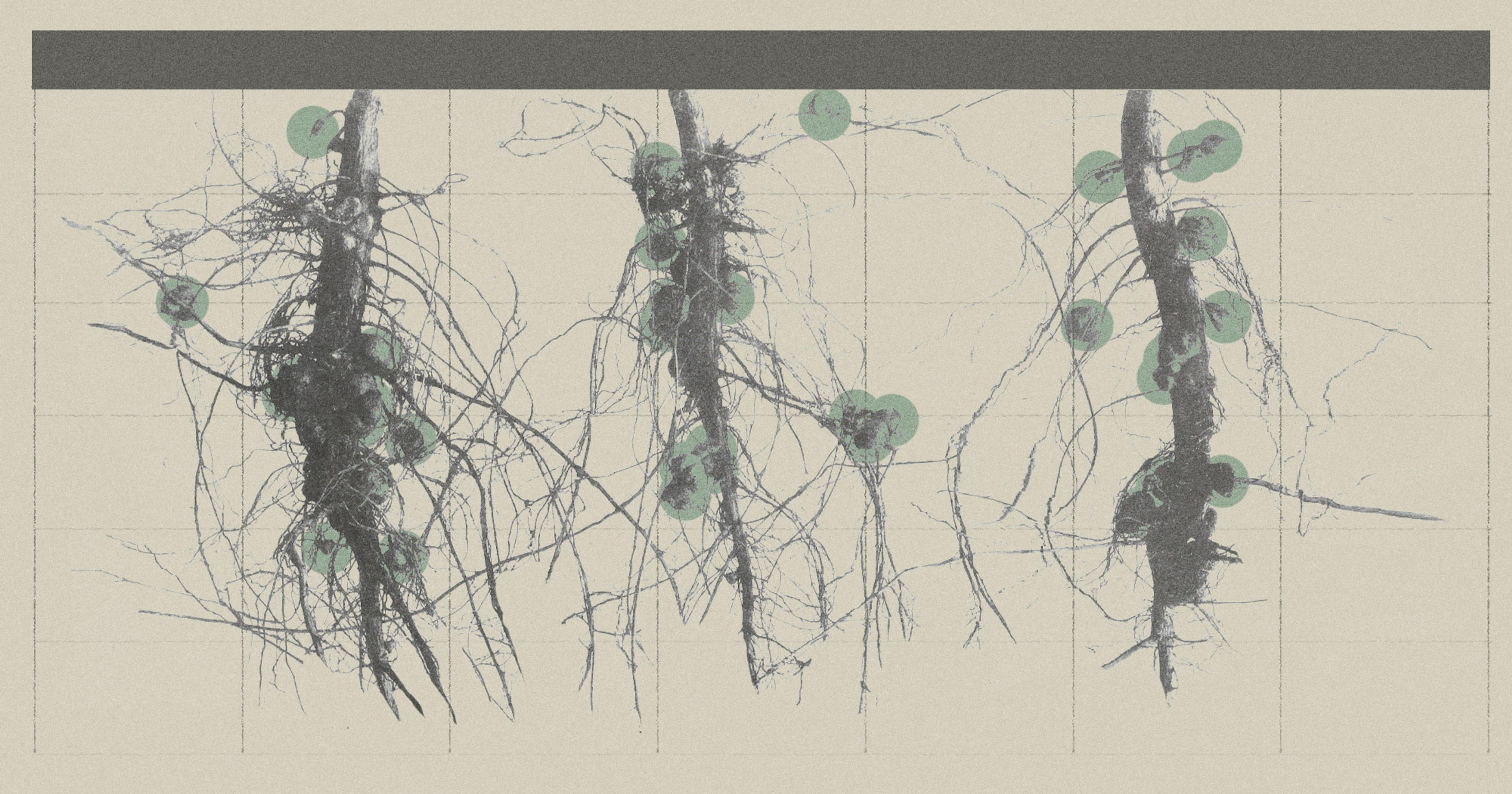

“Solar panels operate more efficiently with cooler temperatures underneath. So when there’s transpiration happening from the plants underneath, it actually cools the panels, allowing them to be more efficient,” he explained. The shade created by the solar panels also creates cooler air beneath during the day and warmer air at night, which encourages moisture retention in the soil.

“From the agricultural side, you’re using less water, which is huge, especially here in the West and Southwest,” he added. “Agriculture currently consumes 70% of all water in our country. We need it to produce the food, but if we start to cut that by certain percentages, it adds up.”

Byron Kominek, who runs the largest commercially active agrivoltaic system in the country, has seen this benefit firsthand at his operation in Longmont, Colorado. Kominek’s farm includes Jack’s Solar Garden, a five-acre plot that integrates produce, pollinator habitat, and raised solar panels that produce energy Kominek sells to local utilities.

“This April was one of the driest months on record for Colorado. The brome and alfalfa underneath my solar array was brighter, greener and bigger than what I have on my other pastures outside of the solar array — that stuff is still dormant or brown,” Kominek said, noting that this is true despite the fact that there’s no irrigation underneath his solar panels.

“The brome and alfalfa underneath my solar array was brighter, greener and bigger than what I have on my other pastures.”

He’s partnering with researchers from Colorado State University, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the University of Arizona and other organizations to gather and disseminate information about agrivoltaic best practices that might be useful for other farmers, and he created the non-profit Colorado Agrivoltaic Learning Center to educate the public about their findings.

His hope is that, armed with the right information, solar companies, farmers and the government can come together around a shared understanding of what responsible land management might look like.

“All too often developers are just looking at the next year — they’re going to build this thing as cheap as they can, sell it off, then they’re off to the next project. They’re not really considering what the land is going to be like for the next 30 or 40 years,” he said. “But that’s what government and community should be thinking of — not just short-term turnaround for some business to get rich while the community deals with thousands of acres that are unusable.”

That sense that land being converted to solar means a loss for farming communities can represent a real obstacle to the buildout of solar in rural areas. Locals who perceive solar as an eyesore, connect development to an assault on their identity as a farming community or feel that solar under-delivers on its promise of financial benefits understandably resist it.

That’s one reason why, said Dr. Zhang, agrivoltaic approaches represent such a positive opportunity: they may be a win-win for renewable energy champions and agricultural communities alike. But for that win to be possible, Zhang believes education about agrivoltaics has to improve.

“If the public cannot distinguish between those two types of solar farms” — meaning single-use land that’s just developed for solar, versus agrivoltaic systems that combine farming and solar — “there’s not going to be much incentive for a developer to do anything different [than install solar arrays on single-use land],” Dr. Zhang said. He also believes that government incentives could make it more appealing for developers to collaborate with farmers on joint land use, rather than just installing panels and spreading gravel underneath.

Though Kansas State University associate professor of agricultural policy Jennifer Ifft sees the appeal of combining solar and farming, she cautions against treating agrivoltaics as the right option for every farmer everywhere. So many different factors need to be taken into account: is the land in question suitable for solar development? Is it near the right kind of energy infrastructure? What local laws exist that might restrict the size of system a farmer can install? Does the farmer have the capital necessary to invest up front in installation? These kinds of questions deserve careful consideration before making the leap, she notes.

Government incentives heavily shape the viability of solar installations for farmers. The foremost among these incentives is the USDA’s Rural Energy for America Program (REAP), which can provide grants that cover up to 25% of equipment and installation costs and loans that cover up to 75% of total eligible project costs. Other incentives vary widely from state to state and can change over time. It took Wishall longer to be paid back for his solar investments eight-plus years ago, but he said that the incentives available in Illinois are so favorable now that most of his neighbors who install solar today “have gotten 100% of their original investment back within one tax cycle.” Tatum, from the American Farmland Trust, said he’s typically seen a five- to seven-year return on investment; Fulton of Straight Up Solar estimates the number at less than five years in Illinois, and closer to ten years in Missouri.

In short, the numbers vary depending on where you are. Hickey recommends interested growers check out the Database of State Incentives for Renewables and Efficiency (DSIRE), a project run out of North Carolina State University, for exploring what’s available near them. Another useful resource is the AgriSolar Clearinghouse, a project funded by the Department of Energy, which provides agrivoltaics expertise to businesses, farmers and researchers. The organization maintains an extensive library of relevant information online, runs a peer-to-peer mentor group, and fields calls from farmers who are looking to get into solar.

Dr. Stacie Peterson, the Montana-based manager of AgriSolar Clearinghouse, said that the goal is to equip growers with information that’s as relevant to their area as possible. “I got a call from a person in Texas yesterday, and they’re trying to decide whether to switch their oil and gas lease to a solar farm,” she said. “So the first thing we do is try to figure out what their goals are, what type of crops they have, what type of water… Everything’s really customized; it’s about trying to figure out who best to connect them to within our organization.”

“Five years ago, there were only a couple of these types of projects, and there are hundreds now.”

For all the excitement about integrating solar and agriculture, more research will go a long way toward helping growers decipher what makes the most sense for them based on the particularities of their operation. But Dr. Peterson said momentum is building.

“I’m seeing rapid adoption. Five years ago, there were only a couple of these types of projects, and there’s hundreds now — and a lot more are coming within the next five years,” she said. “As there are more studies and more understanding, I think that this will start to be part of more and more solar as it’s built.”