Researchers say we need better metrics, and to make sure those scores aren’t based on carbon credits alone.

Last September, Google announced that at some unspecified “soon” point, its platform would offer users searching for recipes a breakdown of the climate impacts of ingredients, using data from the UN — seemingly referencing a composite of metrics produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other sources. Google presented this feature as an expansion of its efforts to reduce its own corporate footprint (and did not immediately respond to a request for more details about it).

With beef shown to be the highest emitter of all ingredients by a longshot, followed by lamb, shellfish, cheese, fish, pork, poultry, and eggs, American ranchers were (unsurprisingly) none too pleased about Google’s accounting. They blasted the tech company for neglecting to account for livestock’s environmental benefits, like preserving greenspace.

But Google did receive accolades from sustainable agriculture advocates, as ClimateWire reported, who applauded the presentation of emissions information to the general public as a generally good idea. Lots of food companies agree; Numi Tea, Oatly, Just Salads, and Unilever’s food brands are now reporting, or will report, greenhouse gas emissions data on labels. The question is where all this data is coming from, and what it actually means when it’s tallied.

That question has been on the mind of Emily Moberg, a director in the World Wildlife Fund (WWF)’s Markets Institute. She authored a new report highlighting that the ways companies account for their greenhouse gas footprints often don’t add up. The problem is exemplified by the food sector where, the researchers wrote, 70 percent of emissions “come from farms, [so] companies need to collect data and calculate impact far upstream from buyers” — what are called Scope 3 emissions. (According to the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, Scope 1 means a company’s direct emissions like running its trucks; Scope 2 means emissions from energy a company buys to light its offices, say; Scope 3 means emissions elsewhere along the supply chain, such as from growing and transporting and processing food and getting the finished product into the hands of consumers.)

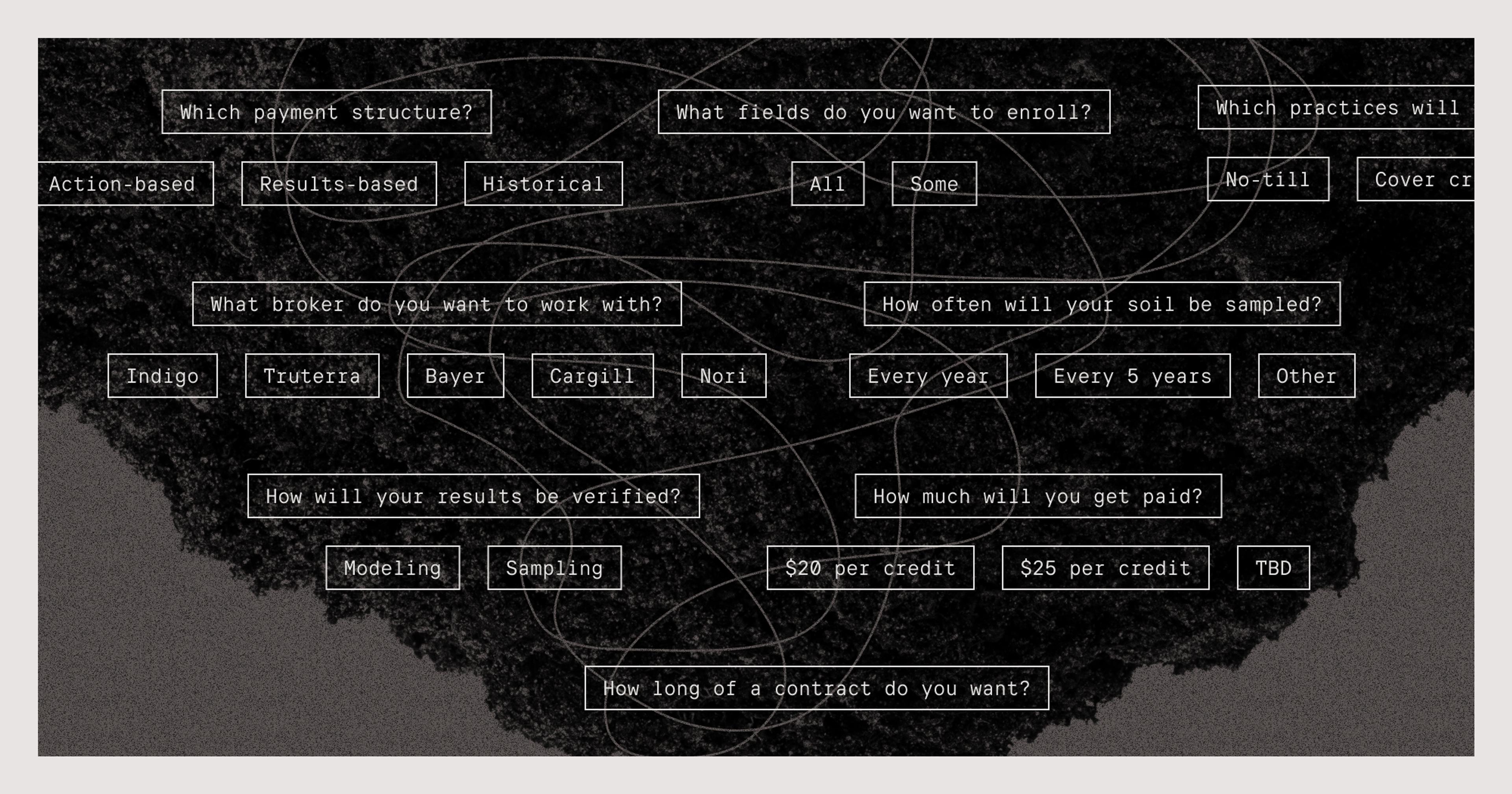

How do you account for all that, mused Moberg, when “food is produced from 500 million or so farms globally, with lots of different flavors, and thousands and thousands of processing plants? You can’t do a full lifecycle assessment for every single farm and every single product, every month of the year — that’s just infeasible. How do we get some of that information in a way that’s credible and comparable?”

Many companies rely on averages. In some instances, these are global “proxies to say an average cow, no matter where it lives, produces x amount of methane simply by its biology; or an average cow drinks 50 gallons of water per day,” said Irina Gerry, CMO of food tech company Change Foods. In addition to these “big picture numbers,” researchers say there’s sometimes enough available data to factor in regional or even country-specific info — not as detailed as farm-level data but also not as broad as those global averages.

Even so, wrote the WWF researchers, “When companies estimate or aggregate emissions from suppliers using different methods, the results are apples and oranges. Comparing emissions measured with or cobbled together with different ‘yardsticks’ does not yield decision-relevant insights or monitoring for impact, because measurement differences mask real performance differences.”

Such broad averages aren’t necessarily terrible, said Dave duVerle, CEO of a climate impact analytics company called Tenko, as long as they’re “taking into account things like producing the wrapper, waste, using fossil fuels. This is a framework that tells you you should take into consideration all these things from the whole life cycle assessment, from the production to everything around it.” This can at least get you in the ballpark of what you need to know about the impacts of a specific food or food product.

“Even foods that are looking pretty good are going to need deep decarbonization.”

Elaborated Richard Waite, a senior research associate with research nonprofit World Resources Institute (WRI), “There’s certain food types that have higher emissions and there’s certain food types that have lower emissions,” and that can be a starting point for companies to see where and how they should begin to reduce their footprints. (Moberg pointed out, though, that such broad accounting detracts from the reality that “even foods that are looking pretty good are going to need deep decarbonization” to get the planet anywhere near keeping global warming below 2 degrees Celsius in the next decade.)

Averages solve for an enormous problem, which is the cost and monumental effort of accounting for every ingredient in a supply chain. When you “track it down to the source, right to the farm, you can say this farm has this many cows in this environment — this is how much water, how much land, how many emissions per pound of milk or meat it’s producing,” said Gerry. “It’s almost untenable because this farm is different than that farm is different than that farm, but as a manufacturer, I might have 500 of these farms in my supply chain. I cannot go ahead and do this kind of in-depth analysis on all of them,” which means assessments of emissions are incomplete.

Explained duVerle, “Carbon accounting is hugely context dependent.” Many researchers would like GHG accounting to incorporate increasingly better regional, then national and sub-national information, to measure the impacts of a cow in water-stressed California versus one in damp New York versus one in Brazil — which deforests the Amazon to accommodate cattle. Companies accounting in this way “can have a huge, huge impact,” said Moberg.

But again, a lack of standardized metrics makes it difficult to “compare footprints and progress against emissions targets between companies that use different standards for the same products,” the WWF researchers wrote. Without standardized standards, “We have this huge gap,” Moberg said.

WRI’s Waite is part of a team that’s developing a greenhouse gas accounting standard for the agriculture and forestry sectors. “Basically, it’s accounting guidance that’s supposed to apply to all companies trying to measure the greenhouse gas emissions in their operations or in their supply chain,” he said.

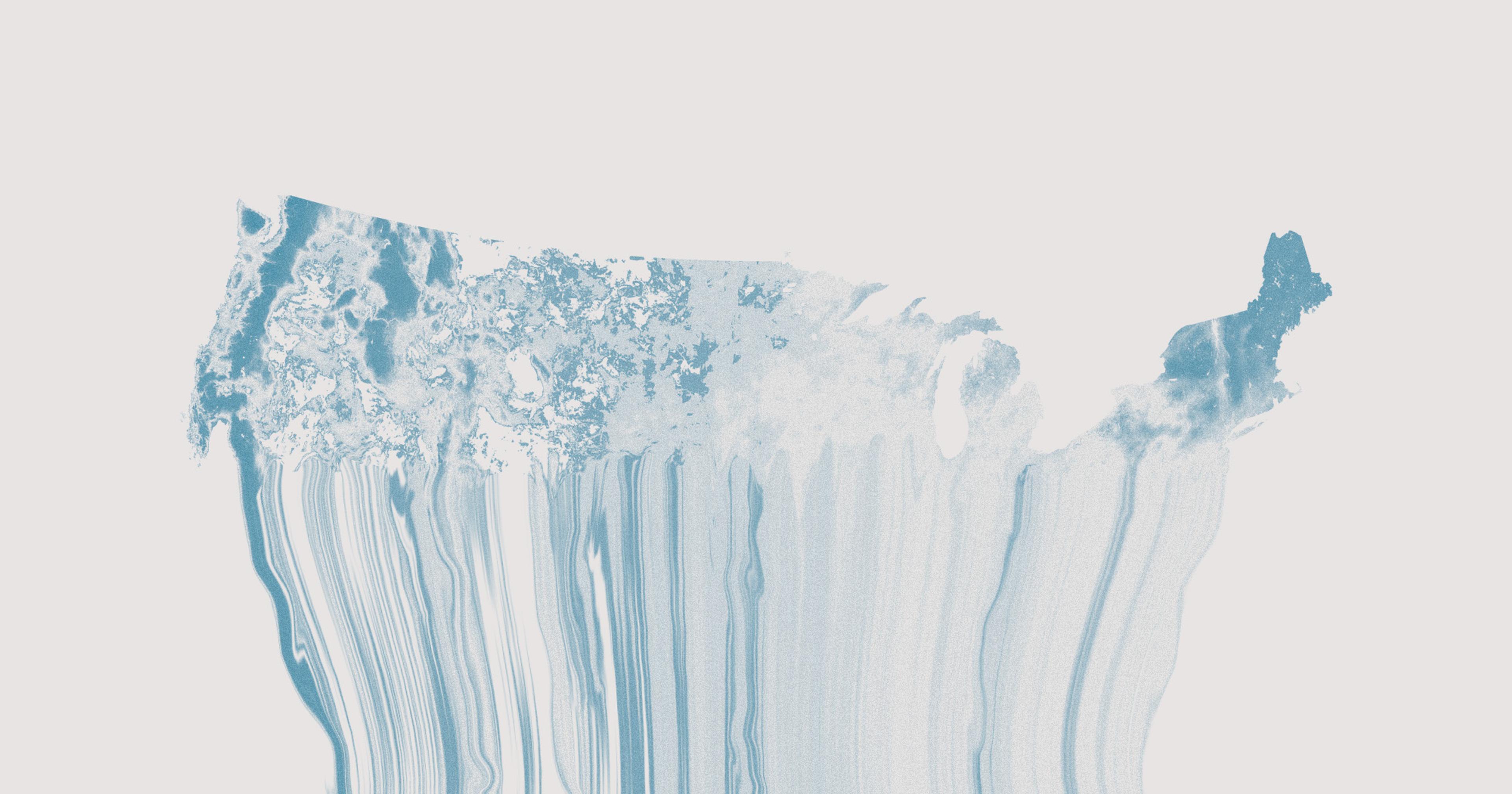

“There is nowhere near enough land to plant trees in the world to offset even a fraction of what people want to offset.”

This might also help with the issue of food companies’ use of carbon offsets to factor their GHG emissions. “Most accounting standards are clear that companies shouldn’t use offsets in their product or corporate accounting to show progress on decarbonization or climate targets, but clearly many companies are doing so,” wrote Moberg in an email. Using offsets can amount to greenwashing, since companies might rely on these rather than actual changes to operations to claim they’re lowering emissions.

Jonas de Lange is growth marketer for food and beverage carbon accounting company CarbonCloud (which calculated Oatly’s emissions). CarbonCloud does not factor in offsets, he wrote in an email, because, “1, There are too many uncertainties around the quality of carbon credits for us to recognise them as a well-functioning tool. 2, Credits are technically outside of the lifecycle of a product and is thus an add-on to the footprint not a part of it.”

Said Tenko’s duVerle, “There is nowhere near enough land to plant trees in the world to offset even a fraction of what people want to offset.” Even in good-faith scenarios, “when you claim that you are going to plant an acre of forest to develop an acre of forest, you’re relying on a lot of hypotheses that are just not verified.” Not to mention, he continued, “the irony of California, where you literally have carbon credit forests that have gone up in ashes due to wildfires.”

While agriculture and other industries wait for standardized emissions data, let alone for any governmental regulations that might see them implemented, “If you’re a company with a climate commitment, you should be thinking about reducing your emissions as quickly as possible, by 90 percent,” said Waite. “If you’re using industry average data, okay, at least you’re measuring it and that’s good. But you can start thinking about actions that you could do to lower it.”