After years of transporting students, used school buses get a second life as a specialty farm tool.

This summer while traveling on Interstate 95 in South Carolina, I noticed a strange sight. As I headed south, a virtual parade of perhaps a half dozen old school buses was headed in the opposite direction. Well, they used to be old school buses. Now they were something different.

The buses had large holes cut into their sides and roofs and were painted white. They also had “Jose Gracia Harvesting” hand painted on the side. The aesthetics immediately caught my eye — they still resembled a bus but were clearly no longer being used for their original purpose. They reminded me of some kind of do-it-yourself project, perhaps a homemade attempt at an RV, but the customization seemed to be standardized among the fleet.

I snapped a slightly blurry photo of the buses when they passed; my curiosity was stirred. Once home, I began to do some sleuthing, which led me on a journey talking to farmers and harvesters across the southeastern United States.

It turns out that the small caravan of buses I happened to pass are a somewhat hidden lynchpin in the complex process of getting food — melons, specifically — from farm fields to tables. In fact, for watermelon farmers and harvesters, used school buses seem to be the dominant way to transport their delicate fruits out of the fields.

The growing of watermelons, like many food crops, has become less labor-intensive over time, with plastic used in the fields to control weeds and drip irrigation to automatically water the plants. But the harvest process is still incredibly manual by nature — watermelons bruise quite easily. Several workers typically act as a human conveyor belt, passing melons to each other and ultimately loading them into a vehicle for transport. Many large farmers turn to third-party harvesting companies for labor and equipment to get the watermelons out of the fields, into packing facilities, and ultimately onto store shelves.

Dustin Land is co-owner of D&M Farms in the Florida Panhandle. He grew watermelons for several years, though he has recently transitioned his land away from melons to focus on other crops including peanuts, cotton, and corn.

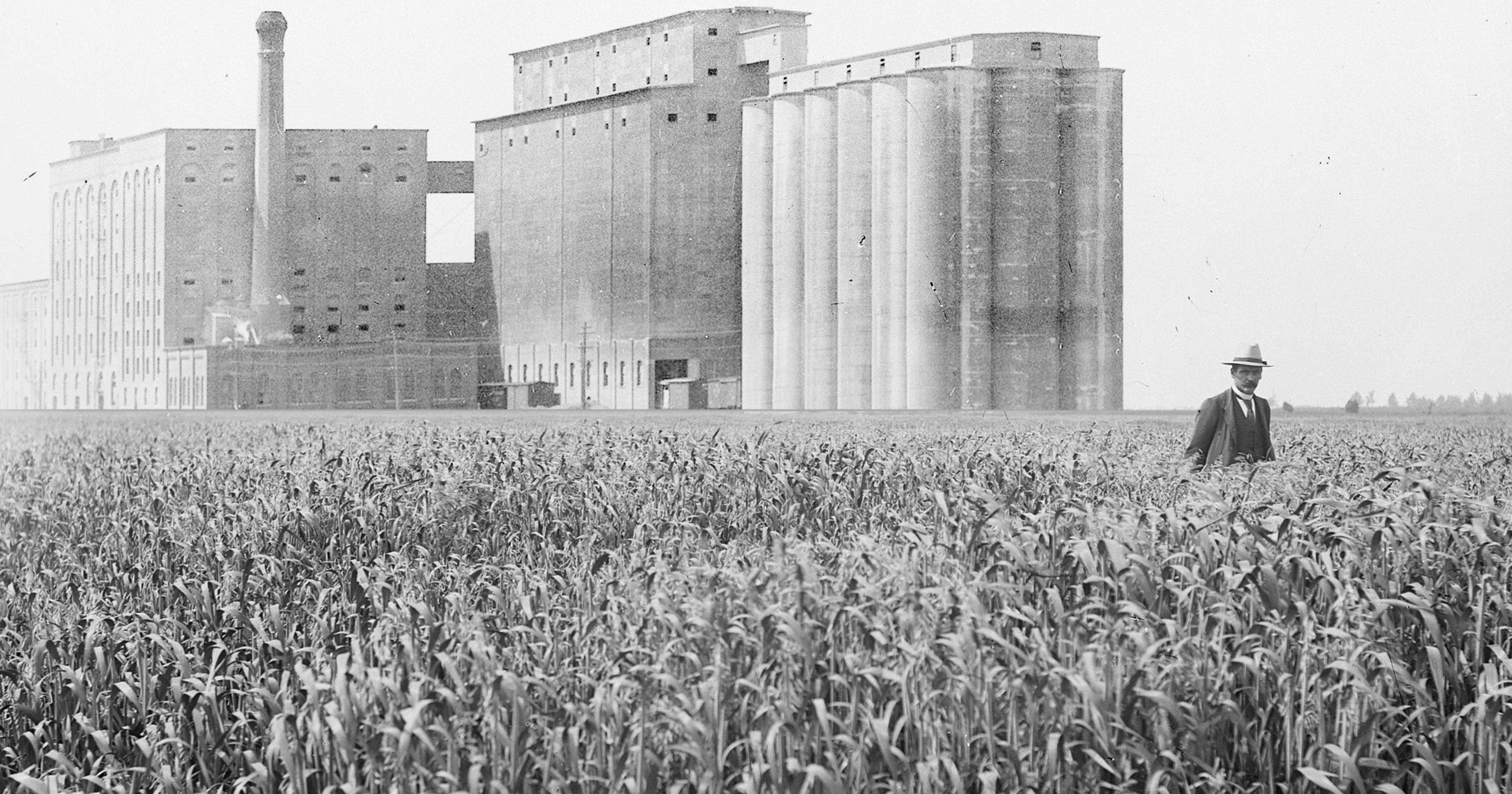

Watermelon unloading in Immokalee, Florida

“Watermelons are a very high-risk, high-reward crop. About one out of every five years you’ll do really well,” Land explained. This is because watermelons are especially vulnerable to rainy weather, which can cause rot or even exploding fruit. But Land also found that suppliers would often reject watermelon shipments for tiny defects.

“If you have a bad year, you’ve just lost all your money. We lost $700,000 in 2021. Just from watermelons.”

At the height of his watermelon growing, Land estimates that he devoted 200 acres to watermelon production, yielding around 80,000 pounds per acre. With only five to seven employees, there’s no way that he could have handled that volume of watermelon without a third-party harvester, especially considering how short the harvest season is in Florida. “Somewhere around the 5th to the 10th of June is when we would start harvest. And then we’d pick up to about the 3rd of July,” he said.

Jose Gracia, whose buses I first spotted on the highway, is the owner of Jose Gracia Harvesting in Frost Proof, Florida. Gracia has been in the business of harvesting watermelons for nearly 40 years. The half dozen of his buses that I happened to pass over the summer are but a small part of his fleet.

“We got about 300 school buses,” he recently told me by phone.

Gracia remembers a time before buses were so dominant in the industry. “It’s been at least close to 20 years since we started using buses. Before we used wagons or field trucks.”

“It takes maybe one day to, you know, have us strip down the bus, cut it, take the seats out and, you know, and have it ready.”

Gracia and others in the industry began to move towards buses because the cost for a used bus is “anywhere from $2,500 to $5,000,” a steal for any piece of farm equipment. When he buys a used bus, he pays a body shop an additional $1,200 to remove the seats and cut large holes in the sides, which makes it easier to load watermelons in the field.

Harvesting companies begin the season in the South and tend to move northward as the ripening season changes.

According to Gracia, the drier weather further north leads to a longer harvest season. “North Carolina, you got 10 weeks. Delaware, you got 10 weeks. Georgia, you got seven, eight weeks. In Florida, you’re talking about six weeks.”

(In 2022, Gracia’s company was ordered to pay $249,000 in back wages and fines by the U.S. Department of Labor for providing unsafe and unsanitary housing and working conditions. Citations like these are especially common among third-party contractors like Gracia’s, which provide incidental labor to farmers, with 70% of investigations conducted between 2000 and 2019 resulting in violations.)

Manuel Barajas, owner of TM Harvesting in Lake Placid, Florida, has been in the harvesting business for 24 years. Barajas’ crews also travel with the harvest season. “We start in May in Florida, Central Florida, then in June we’re in Georgia, and mid-July to August we’re in Maryland.”

Photo courtesy of Jose Gracia

It can vary by the acreage of the farm, but Barajas sends a crew of about 50 people to a farm at a time, and that crew remains at that farm during the harvest cycle before heading north to work the next farm.

Barajas estimates that his fleet is about 27 buses, which he stores locally in the states where he has crews working rather than transport the vehicles between cities.

Barajas explained that used school buses are really just truck engines and chassises with a different body style. “If I’m going to buy a [used] truck, like a flatbed truck, that truck with the same motor, same horsepower, same transmission, it’s going to be about $10,000. And if I buy a school bus, because it’s been sold by the school board, by the government, I can get it for $3,000.”

Barajas usually has his own team transform a bus from a student hauler to a watermelon carrier. “It takes maybe one day to, you know, have us strip down the bus, cut it, take the seats out and, you know, and have it ready.”

When Barajas is in the market for a new (used) bus, there are certain features that he’s seeking.

“We try to avoid the handicapped buses. We try to get away from them because they have the doors on the side, and that makes the body weaker. So when you load them with watermelon, it’s really heavy. They start to bend from the back.”

“Any little glitch, it doesn’t work and you gotta find a sensor and the regular mechanic doesn’t know how to fix it ... that’s why we try to buy nothing newer than 2002.”

He also prefers older buses because new buses are loaded with too much technology. “Everything is a sensor. And then, you know, any little glitch, it doesn’t work and you gotta find a sensor and the regular mechanic doesn’t know how to fix it. You gotta take it to the dealer and they gotta put a computer in it and all that kind of stuff. So that’s why we try to buy nothing newer than 2002.”

Barajas said that buses are common in the watermelon industry, but he’s also seen them used for other crops. “A lot of people in North Carolina use them for sweet potato hauling. The farmers use them for a lot of things. They cut them off and make them water trucks. You cut them off and you put like a flatbed and then they put little boxes on the buses.”

Unmodified school buses with the seats and walls intact are also sometimes purchased by the harvesters and used as transportation for farmworkers. Barajas described to me how he often will start with a transport bus and eventually convert it to a hauler as it ages. “If I have a labor bus four or five years, I might turn that one into a watermelon bus and buy a newer labor bus. And then I might retire one of my older buses and make use [of it] for parts.”

A pickup truck or tractor could substitute for the bus, but they wouldn’t hold nearly as many large melons and would require many more trips. It’s representative of the creative problem solving facing farmers and agricultural workers. Tight margins lead to solutions that make smart, cost-effective reuse of scrap materials.

I suspect that most people in the general public have no idea where their busted-up old bus goes after dropping off its last student. Conversely, everybody in the watermelon industry seems to take it as a matter of course.