Nutrition experts say this year’s bill should give more funding and focus to farmers who grow the food we should be eating.

A prevailing irony perpetuated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is that its definition of a “specialty crop” has nothing to do with produce grown for a niche market — açai berries or rambutan, finger limes or bamboo shoots. Instead, the term distinguishes regular old fruits and vegetables, as well as legumes and nuts, from commodity crops like corn, soy, and wheat. Its usage highlights just how much USDA has historically back-burnered many food crops, said Sarah Carden, a Rochester, New York, organic vegetable farmer and senior policy advocate at anti-monopoly nonprofit Farm Action.

As you likely know, 2023 is a Farm Bill reauthorization year, a once-every-half-decade event in which billions of dollars ($428 billion in 2018) are funneled by Congress into USDA coffers to run agriculture and food programs. On the mind of some progressive legislators and food security advocates is how to make the Farm Bill more nutrition-centric. They’re beginning to talk about specialty crops and how better supporting the farmers who grow them — over the production of corn for ethanol, soy for cattle feed, and wheat that ends up in processed foods — could help Americans eat more nutritiously.

“Farmers who … have an interest in growing food that addresses the nutrition crisis need a farm bill that will empower them to produce” fruits and vegetables, Carden said. She and other progressive policy wonks are optimistic that Americans are itching for this kind of change. But what could that look like in practice?

In 2018, less than 0.5% of Farm Bill funding went to one of 12 sections, or titles: the Horticulture title, which is where most funding for specialty crop and organic growers comes from; it gives grants to support farmer’s markets, for example. By contrast, 80% of Farm Bill funding went to the Nutrition title, which supports food assistance like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly food stamps) and the Emergency Food Assistance Program.

Five percent of funding went to the Commodity title, which gives direct price and income supports to producers of “staple” commodities like corn, soy, and wheat; these producers, as well as meat producers, also benefit from the Crop Insurance title, which accounted for 8% of Farm Bill funding; smaller and speciality crop farmers can be eligible for funding through this title but according to Carden, it works “far better” for commodity growers, who use up the bulk of its resources.

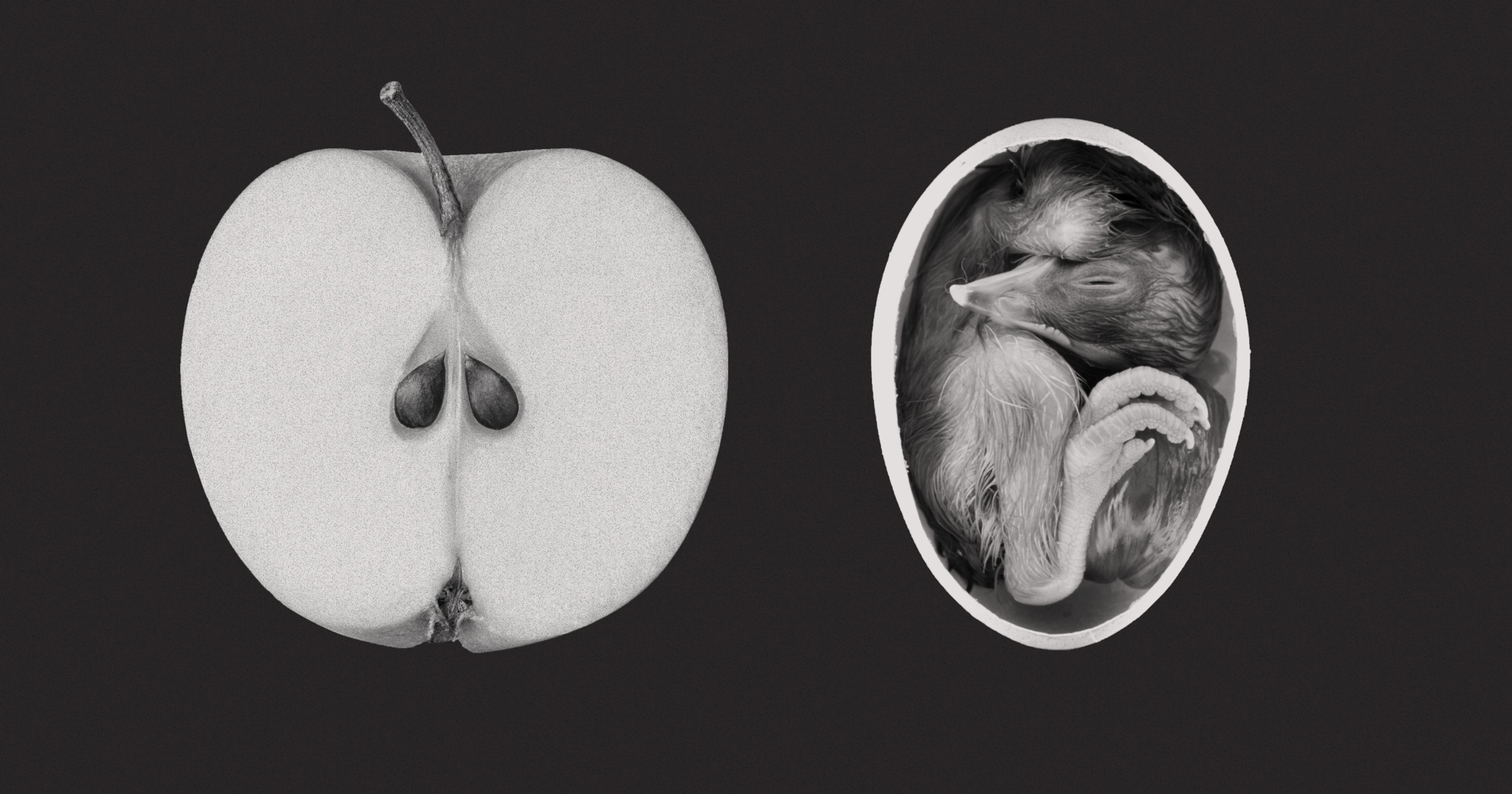

“There’s a reason why none of us are eating enough vegetables and it’s more than just people don’t like to eat them,” she said. “The Farm Bill has a huge amount of control over who farms, what they farm, how they farm, and, by extension, what people eat.” By way of example, she mentions her corn- and soy-growing neighbor: “It’s not that he’s like, ‘I love corn and soybeans.’ But he loves farming, he loves to make a living, and that’s the smart way to make a living doing farming,” she said, due to the money USDA makes available to producers like him. On the other hand, the “mission-driven” organic vegetable farm she and her husband run has never received crop insurance or subsidies. Additionally, “I have very little access to the kinds of technical assistance I need,” she said. Farm Action is calling for Farm Bill changes that would allow her better access to all three.

“Helping [consumers] to eat more healthy foods also means increased dollars going to the farmers who grow them,” said Christina Badaracco, a registered dietician and co-author of the book The Farm Bill: A Citizen’s Guide, which explains the bulky, sometimes arcane legislation for a lay audience. “When we look at our systems of subsidies and crop insurance, we need to think about expanding the types of producers who are eligible.” That should better include smaller farmers of so-called specialty crops that are “really what just about everybody would think should be filling the largest portion of people’s plates,” Badaracco said.

“When we look at our subsidies and crop insurance, we need to think about expanding the types of producers who are eligible.”

William Hoagland is senior vice president of the Bipartisan Policy Center and a former administrator at USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service. “Should we be providing more subsidies … to smaller producers of fruits and vegetables? That would be beneficial from a nutrition perspective,” he said. “But I don’t think you’re going to convince traditional farm organizations like the American Farm Bureau and the American Soybean Association that” their members are not producing foods important to American consumers.

The American Farm Bureau Federation, which The Nation points out “positions itself as the voice of the farmer,” released a survey showing that Americans trusted farmers and wanted Farm Bill reauthorization, although its questions made no distinction between row crop and specialty crop producers. A 2022 Farm Bureau market report outlined some of the frustrations of specialty crop producers and concluded that “it is important to consider the unique market challenges facing specialty crop producers and the current farm bill provisions in place to make informed future recommendations” — although it stopped short of openly advocating for them. The Farm Bureau did not respond to a request for comment but in a press release, its president, Zippy Duvall, said, “Thanks to the farm bill, farmers and ranchers can hold on through the tough times to keep the nation’s food supply secure.”

The 2018 Farm Bill was considered status quo by Farm Bill watchers, including Hoagland; it didn’t manage to shake up Farm Bill business-as-usual or shake off the heavy lobbying arm of Big Ag that Hoagland alludes to. Carden, however, believes there’s a chance to make change in 2023. “This farm system that has prioritized corporate interests … has failed us. [2020’s] empty shelves scared people,” she said.

Already, she pointed out, legislators have introduced what are known as marker bills — meant to garner Congressional support in advance of trying to write them into the Farm Bill — that challenge the ag lobby: Sen. Cory Booker’s (D-NJ) Farm System Reform Act that shifts resources away from industrial animal production; Rep. Chellie Pingree (D-ME) and Rep. Dan Newhouse (R-WA)’s Local Farms and Food Act, meant to strengthen local food systems and boost parts of the Nutrition title; and Rep. Earl Blumenauer’s (D-OR) Food and Farm Act, that would increase investment in regional food systems, cap commodity crop subsidies, and expand crop insurance for specialty crop producers, among other reforms.

The issue of crop insurance is especially relevant to helping non-commodity farmers get and stay in business. The 2014 Farm Bill included Whole Farm Revenue Protection (WFRP); it initially served farms with up to $17 million worth of insured revenue, which was expanded recently to $34 million. However, said Carden, this provision is “not very cost-effective for farmers because it’s got this big paperwork burden, and [insurance] agents are not all that incentivized to sell it because it’s really complicated to write and they get more money by acreage.” She said some of the paperwork load had been lately eased but that Farm Action was advocating for more.

“Purchasing foods that are less processed helps ensure a greater percentage of each dollar goes back to the people who actually grew the food.”

Still, actually paying farmers to grow nutritious food could use a boost. The Gus Schumacher Nutritional Incentive grant program (GusNIP) was introduced in 2018 under the Nutrition title; among other things, it gives grants to provide veggie prescriptions to low-income people with certain diet-related diseases. It has so far distributed $257 million and Badaracco thinks it could do some heavier lifting. “A lot of us are hoping GusNIP will be scaled up in [2023] for produce prescriptions in particular, because that involves a specific linkage between … healthy foods and people who are in need,” she said.

In an email she elaborated that nutrition assistance programs more broadly “can help strengthen markets for small, diversified farms because the funds are used to buy foods that are more wholesome and nutrient-dense … Also, purchasing foods that are less processed helps to ensure a greater percentage of each dollar goes back to the people who actually grew the food.” She also pointed out that the Senior Farmers’ Market Nutrition Program funded by the Nutrition title provides benefits to use at farmer’s markets, “which thereby help the local farmers who sell at them.”

Carden agreed that GusNIP has not only shown “really positive health outcomes, but if we keep it tied closely to local procurement and scale it up, it has a lot of potential to support farmers and local communities.” She thinks there’s a good chance it will receive increased funding in the 2023 Farm Bill, along with crop insurance reforms.

Still, not everyone is so bullish about Farm Bill reauthorization prospects. “I don’t think there’s going to be a Farm Bill [until late] in this 118th Congress — after the presidential elections, in a lame duck session in 2024,” said Hoagland, although he said that if Republicans gain the Senate and/or the White House, reauthorization might not happen then, either. He believes that the partisan fighting that’s already broken out over whether to lower SNAP benefits and increase work requirements around the program are a harbinger of what’s to come. It’s “going to create chaos and make the polarization that already exists out there even worse,” he said.