On the strange work of a “climate advice columnist,” and the fallacy of consumer responsibility.

It takes an enormous amount of confidence — delusion, probably — to tell people how to live. This is the perennial conflict of the advice columnist, who reviews the pleas of desperate individuals and attempts to give knowledgeable, compassionate guidance on their most pressing issues.

In the realm of climate-related advice, my remit at the media outlet Grist for about five years, most people would be very happy if some reliable authority figure simply told them what to do. I believe that when you write to an advice columnist, you are asking another person to simplify a complex problem. But the maddening thing about climate change is that every action that mitigates carbon emissions carries unsatisfying caveats or uncertainties — and usually, a presumption that you will have to change ingrained personal habits.

This advice column had existed for over a decade before I took the reins. The older, beloved version offered counsel on individual choices one can make to lead a climate-conscious lifestyle, from the least-toxic household cleaners to the proper disposal of sex toys. Under my authorship, the column would suggest, gently: Perhaps there are systemic causes of ecological collapse that would be more deserving of mental and emotional energy than the merits of making your own coconut oil lube.

I felt an enormous amount of guilt when it came to questions of consumer responsibility. It’s not because I am a particularly reckless or profligate shopper, but I do have a hard time caring about the environmental virtues of one laundry detergent versus another, or the climate consequences of a dead vibrator languishing in the landfill. And yet hundreds of readers had written in over the years because they did care, which made me wonder what was wrong with me, an ostensible environmentalist.

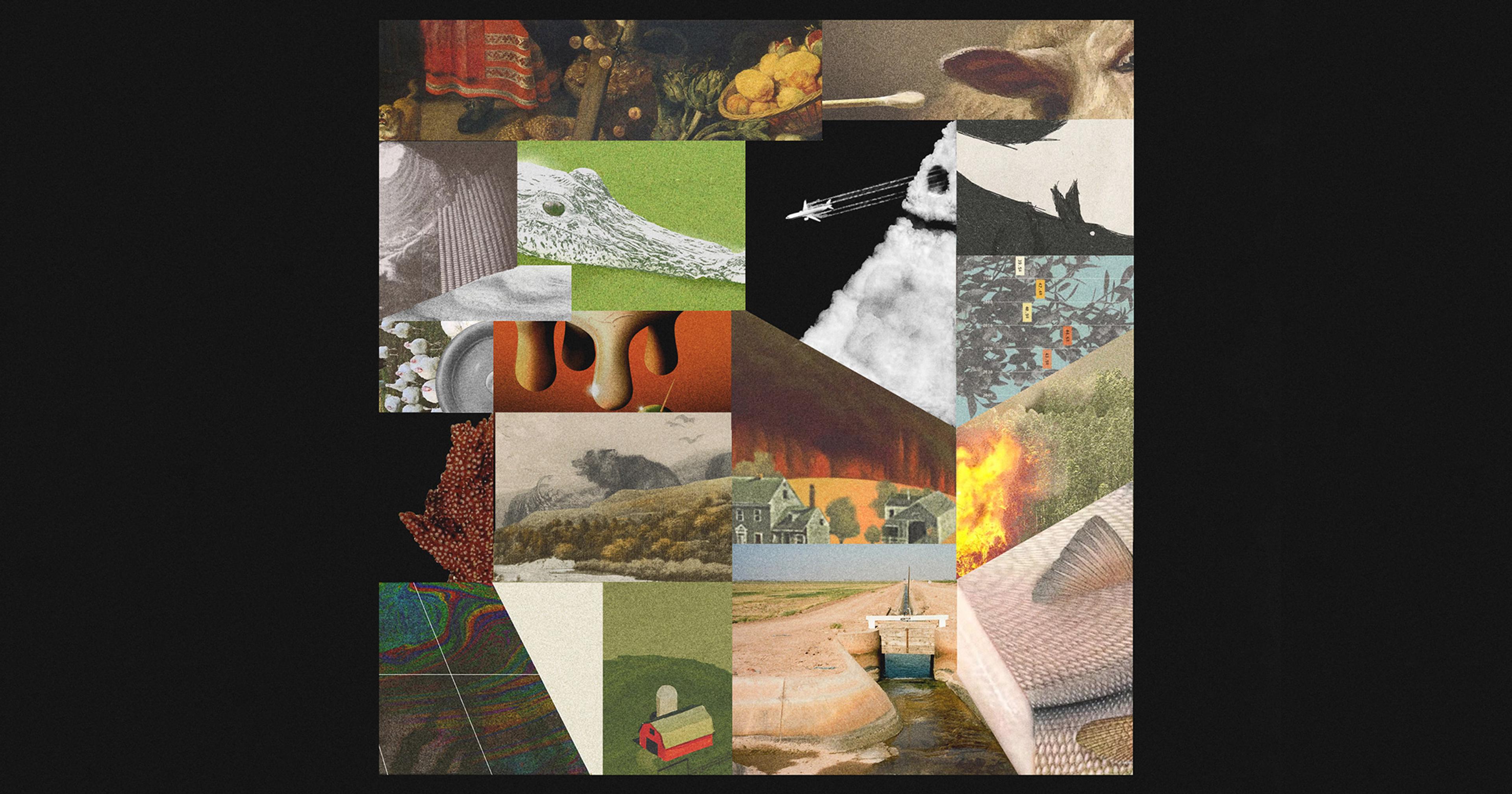

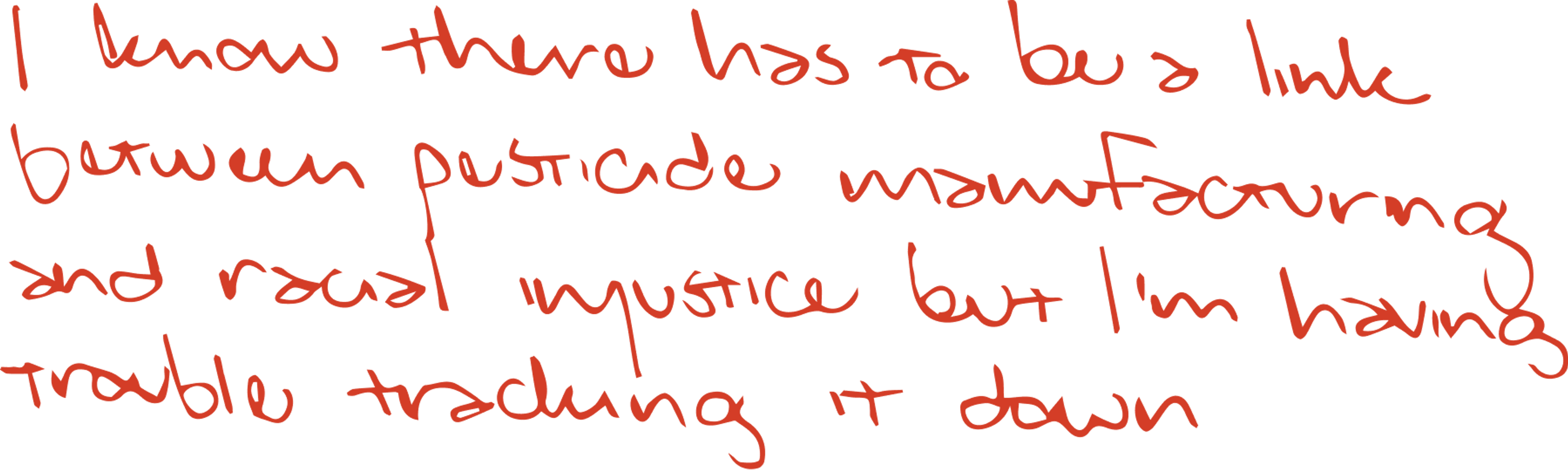

Questions of eating — grocery shopping, meal planning, food waste — do feel like they bridge the gap between consumer responsibility and systemic overhaul. Agriculture occupies an enormous segment of national carbon emissions, and is responsible for any number of crimes in the realm of water contamination and air pollution. And if demand dictates the market, a meaningful consumer movement could theoretically usher in the widespread use of environmentally responsible ag practices.

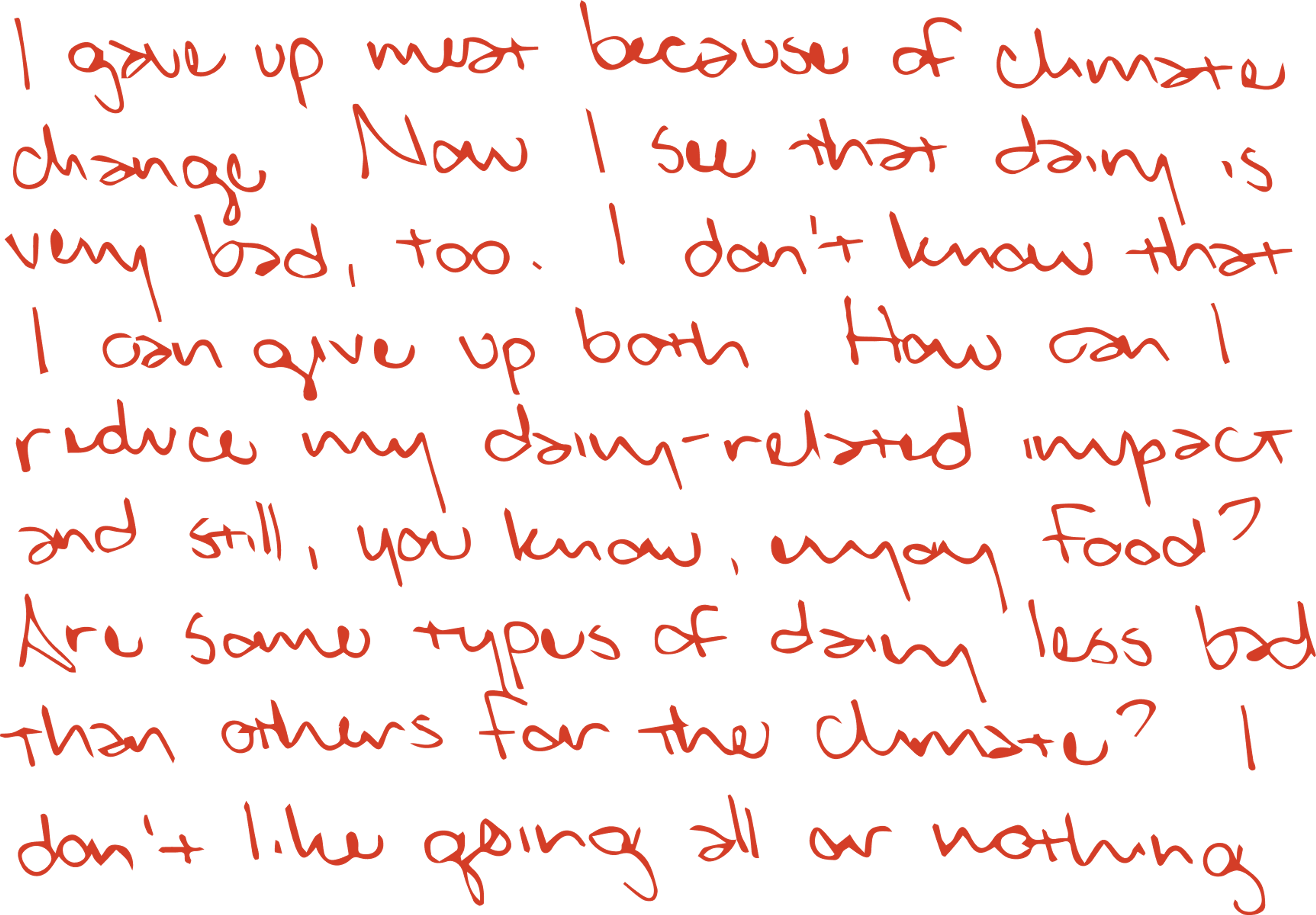

I fielded many questions about which vegetable has the lowest ecological footprint; which forms of dairy are acceptable for a consumer worried about methane; whether seafood is the most climate-sustainable form of protein. I would look at charts and tables and call academic experts and research things like carbon soil sequestration, the relative water intensity of crops, and the sins of various fertilizers. I would respond to curious readers about the best farming practices to preserve soil and climate and water tables, with the helpful guidance that one should seek out food that was grown using those methods.

Therein, the problem. The unfortunate truth is, as a consumer, the main indicator of how a potato is farmed or a cow is raised is the produce sticker or package label. These labels are famously amorphous and unreliable. Gallons of ink have been spilled over the utter meaninglessness of the “natural” label, the debatable virtue of “organic,” the ambiguity of “cage-free” and “pasture-raised,” and the unverifiability of “regenerative” or “low-carbon.” And even if you accept that such signposts are fallible, you may be discouraged to learn that even the farmers with the most environmentally conscious intentions are, for example, relying on rather tenuous and theoretical calculations to certify their fields as carbon-positive.

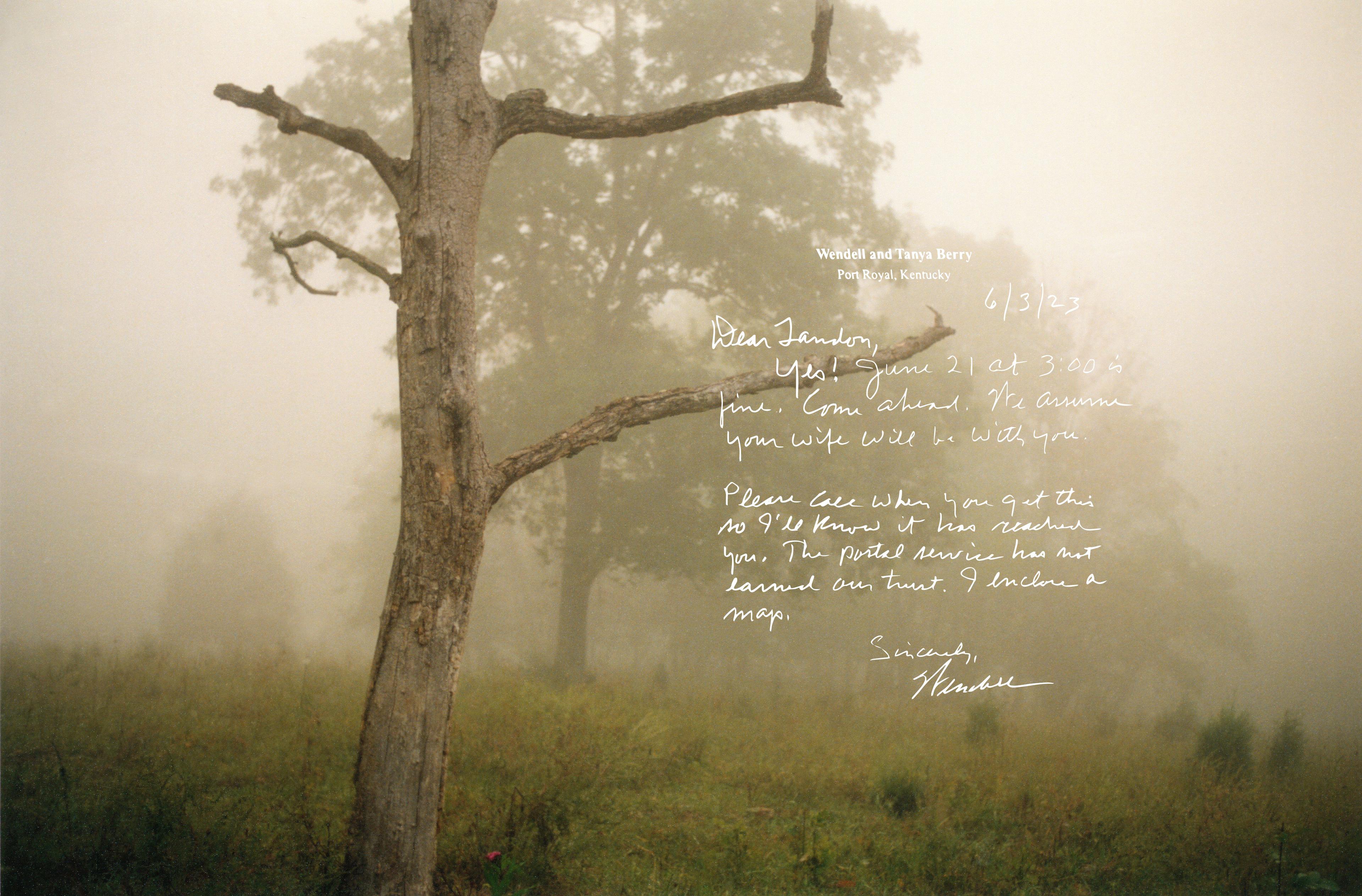

Not very satisfying! And if grocery store aisles are a sea of lies, where do you go? There was an oft-used dictum in the early days of the Slow Food movement: “Know your farmer.” You may have seen it on a canvas tote bag in jaunty serif font. The implication was that one could have faith in the environmental and nutritional integrity of one’s food only by understanding its source, a feat presumptively accomplished by shopping at farmer’s markets, researching direct-purchase farm shares, and getting deeply involved with your local co-op.

This school of sourcing doesn’t necessarily accomplish a more climate-friendly food system. It does, however, suggest a more decentralized one where consumers and farmers are separated by fewer, more transparent middlemen. This would, in theory, allow for a true free-market exchange: Consumers could convey their desires for more environmentally conscious farming practices to producers, demonstrating that an eager market exists for such products.

But recommending this rather boutique and high-effort method of food shopping, I grew to realize, only fit a fairly passionate segment of the American public — and boy, did I try to join that segment. I believe that if you’re going to give advice, you should at least try to live that advice. Since I was not going to become a farmer, environmentally motivated or otherwise, I started attempting to be the model food shopper.

I carried home pounds of farro from the co-op on my bicycle. I spent a shocking amount of money on meat, poultry, and eggs from small, (ostensibly) sustainable farmers, which partially inspired me to try veganism for a month. I went to two farmer’s markets a week to purchase locally grown produce. I tried CSAs and plant-based meal kit delivery services, and then canceled them due to the expenditure of carbon emissions in transportation and packaging waste. In the ultimate opportunity for the free-market exchange of consumer-producer preferences, I briefly dated an organic farmer and desperately tried not to be bored when he explained his cover crop methodology.

And I began to feel annoyed! I wanted to buy the Perdue chicken because it was cheap and the conventionally farmed supermarket lettuce because it was closer to my apartment, and sometimes I wanted to be lazy and sleep in on Sunday mornings and not walk to the farmer’s market in the relentless Seattle drizzle. I wanted to eat a cheeseburger at a bar and not care about where it came from! I didn’t want to talk about alfalfa on a date! I love food and I love cooking and I wanted it to be easy, not a source of guilt over my own hypocrisy as an alleged expert on climate-friendly lifestyles.

I realized I was building a lot of resentment around maintaining a climate-conscious diet. Conscious is really the operative word here: You can wring hands and shake heads over fast food and Instacart and prepackaged meals of inscrutable origin, but the cultural shift to easy, no-thoughts-required meals has already passed. It is a hard sell to ask someone to go from putting very little work or thought into a basic survival skill (feeding oneself) to devoting hours to research and sourcing.

Yes, among the little segments of our daily lives, the one occupied by food has potential for real planetary impact. And because eating is such a basic part of life, it feels like a logical starting point for reducing one’s carbon footprint. But food is not basic — every bite you take is intricately wrapped up in emotion and habit and comfort and craving. And all of the opacity of the American food system burdens the pursuit of an environmentally sound diet with disheartening and frustrating questions: Why does it require so much extra effort? Why does this cost so much?

As it turned out, I ended up proving to myself the whole point of taking over the column: Placing the onus of staving off climate change on consumer choices is a self-defeating proposition. Convention and ease — to say nothing of affordability — are tempting mistresses, and when you succumb to them you feel disgusted and defeated that the system has won. It’s too much psychological drama to go through for a salad!

In a refreshing departure from the rules of the advice column, there is no tidy lesson or teachable moment here. I only offer the suggestion that a system as Byzantine and beset by problems as American agriculture is not fixed by the insistence that consumers hold the supreme power of change. It’s also a philosophy that embodies a certain sort of hubris, that the one who buys is driven by purer motives than the one who produces. But that, unfortunately, is not as easy to sell on a tote bag.

This article first appeared in Ambrook Research Journal V. 01, a limited-edition print publication.