“The cattle are ready but the lockers are full.”

Ninety-eight percent of marketable meat in the United States is processed at a mere 50 facilities. These large facilities move several thousand head of cattle or hogs a day, with carcasses humming down the production line on their journey toward store shelves and restaurants. You can imagine, then, the destruction that happens when one of these few facilities is closed even for a day. During the first spring of the Covid-19 pandemic, a number of facilities had to shut down for days or even weeks as the result of disease outbreaks among workers, resulting in a 45% loss of capacity nationally for pork and cattle processing. The result was catastrophic in scale. Most immediately, meat became scarce on store shelves and meat prices shot up across the sector, with prices up 18% in May 2020 over May 2019. An analysis from Oklahoma State and the National Cattleman’s Beef Association in April 2020 estimated $13.6 billion in losses across the beef sector. Millions of slaughter-ready animals were euthanized, because there were no facilities available to process them.

Facility closures, alongside Russian hacks of meatpacking giant JBS, revealed the vulnerability in highly concentrated industry. JBS and the other “Big Four” meat companies (Cargill, Tyson, and National Beef) control as much as 85% of the beef market. In 2020, as a result of the massive bottlenecks caused by the closures of major processing plants, farmers looked to get their animals booked at independent plants and small, local meat lockers, which generally process a small quantity of animals for private consumption. For processors, this meant being overwhelmed with orders. By late 2020, many Nebraska processors were booked out through 2022 for cattle and hog processing. This wait time and uncertainty made it impossible for small producers to plan financially. With processors swamped, cattle producers were considering selling off and getting out of the market. “I can’t really plan, you know,” one Nebraska farmer told me, “I have cattle that are ready for slaughter now but the lockers are all full. This might be our last year.”

“I can’t really plan, you know,” one Nebraska farmer told me, “I have cattle that are ready for slaughter now but the lockers are all full. This might be our last year.”

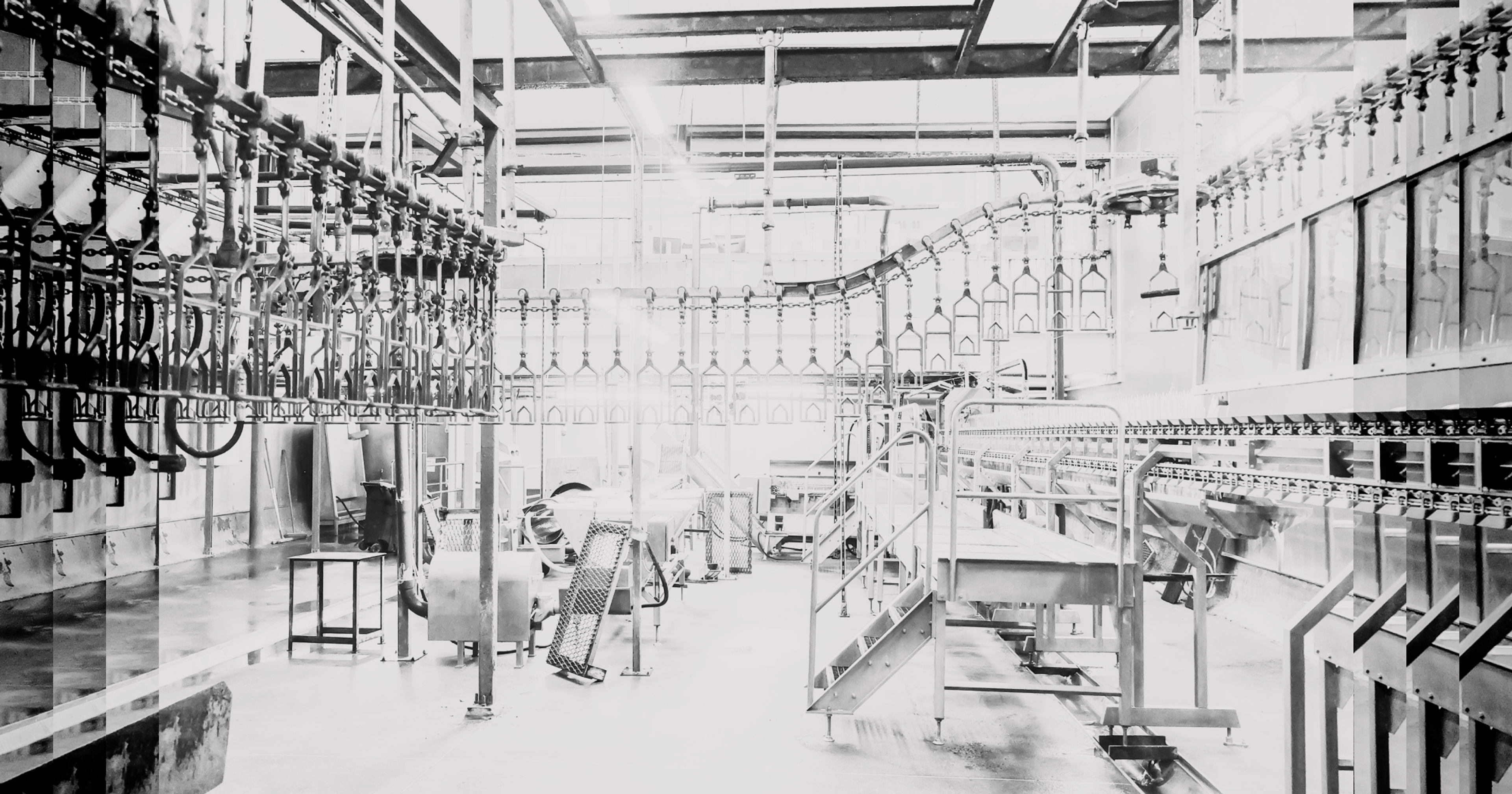

In the wake of these events, a number of states have started grant programs, like Nebraska’s Independent Processor Assistance Program (which still awaits funding appropriations), to help small processors expand their operations. These programs offer funding for independent processors to increase shackle space, expand their facilities, purchase equipment, and train workforce. Without greater shackle or freezer space, a small processor has a definite cap on how many animals it can move through. The pandemic closures demonstrated, however, that these independent processors are the only backstop when the major packers suffer disruption. Many small meat processors saw a 30%-40% year-over-year increase in business during the first year of the pandemic. These operations provided necessary flexibility in getting meat to local markets.

As a result of the continuing effects of the Covid-19 supply chain disruptions, the federal government is also working to spread American processing capacity beyond the big four companies, beginning with a 2021 Executive Order 14017 on America’s Supply Chains. In response to exposed vulnerabilities in the agricultural supply chain, the order called for supply chains that are “secure and diverse — facilitating greater domestic production, a range of supply, built-in redundancy.”

In February of this year, USDA released a major study pursuant to the terms of EO 14017. Chief among USDA’s recommendations are policies that promote competition and transparency in meat markets. For this purpose, USDA and DOJ have created www.farmersfairness.gov, a reporting system where farmers can notify the agencies of anti-competitive practices. In 2021, Chuck Grassley and a number of cosponsors introduced the Special Investigator Act and Cattle Price Discovery and Transparency Act in an effort to uncover exploitative practices on the part of meatpackers that lead to low prices for cattle producers. Negotiated and cash purchases for cattle have been increasingly replaced with formula contracts, where cattle will be signed away at a price to be determined according to a formula by the purchaser at the time of sale, rather than a price negotiated at that time. Without clarity on these formulas, the buyer can stiff a producer. 15 years ago, negotiated or cash sales accounted for more than 50% of cattle sales; today they’re only 20%.

At the same time as members of Congress are pushing for competition, and therefore better prices for a wider set of cattle producers, USDA and states are focusing on regional meat markets. The portion of U.S. agricultural markets dedicated to local and regional sales is small, at around 3%. But it’s on an upward trajectory, growing more than $3 billion in annual sales between 2015 and 2017. Farmers and ranchers are showing increased interest in direct and regional sales, since a larger portion of the revenue in these sales go to the producer than in traditional supply chains. Among these regional support initiatives are the state-level programs mentioned above, a movement to promote Cooperative Interstate Shipment, which allows state-inspected facilities to sell across state lines, and $500 million from USDA in grants for small processors.

In order to promote competition, the USDA is seeking regulatory reform on “Product of USA” labeling through a thorough review of agency practice and FTC enforcement standards, so that foreign products packaged in the United States no longer qualify. It has also launched a new grant program, the Meat and Poultry Processing Expansion Program, for eligible processors to apply for up to $25 million in order to build out facilities, train workers, or otherwise expand capacity.

Another avenue for supporting small processors consists in helping them to bring their plants up to inspection standards. The process of shifting from custom processing, where a butcher processes an animal for private consumption, to inspected processing can be expensive and confusing, and small outfits benefit from assistance in receiving their federal grant of inspection, while the market benefits from a processor’s ability to sell to commercial markets. The USDA will make further grant funding available under the Meat and Poultry Inspection Readiness Grant (MPIRG), and is increasing funding to a program that supports new food supply chain start-ups.

However, farmers and small businesses often have difficulty accessing USDA funds. Grant opportunities often aren’t communicated to their intended audience, and small business owners may have difficulty navigating a complicated application process. For livestock farmers looking to get into processing or farmers interested in opening a cooperative processing facility, for entrepreneurs, and for existing independent processors looking to expand their capacity, a great deal of funding and assistance is now formally available. Whether it will be accessible is another question.

The weakness and vulnerability of the American meat sector was thrown into sharp relief by the pandemic, which has drawn attention to decades-old negative trends for farmers, customers, and independent small businesses. A more diverse set of supply chains in the meat market could provide farmers better profits, customers better meat, and the country a more secure food system.