The grocery aisle makes a lot of promises, but are industrial meat farms living up to their claims?

White Oak Pastures is a sixth-generation, 156-year-old farm in Bluffton, Georgia, that made the bold decision nearly 30 years ago to transition away from industrial agriculture. After decades of crowded barns and antibiotic-laden feed, fourth-generation farmer Will Harris was ready to undertake some radical revisions.

Today, the farm’s animals roam free, grazing on grassy fields and rooting their stout noses in the dirt. All White Oak livestock is raised without antibiotics or hormones. Their products sport labels like Non-GMO, Certified Humane, and Raised Without Antibiotics.

Harris‘ ethics reflects a deeper shift in industrial farming practices that began showing face late in the 21st century. While antibiotics are often attributed to illness prevention, their use became popular in the 1940s as a growth enhancer in livestock feed. Farmers could rapidly raise animals double the size, while using a fraction of the resources.

This “non-therapeutic” antibiotic use was economically rewarding, but concerns about drug residues and antimicrobial resistance began to rise in the 1960s. Antibiotics in food, water, and soil can make their way into our bodies, leading to resistance in human medicine. Antibiotic resistance has been identified by the WHO as “one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development today.”

Calls for the gradual phasing out of antibiotics in livestock started back in the ‘60s, though it took some time to see regulatory movement. Today, the use of these drugs in American livestock is managed by both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA is in charge of testing meat and managing on-package labeling, while the FDA regulates non-medical antibiotic use.

These regulations led to the 1996 establishment of the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS), which tracks antimicrobial resistance in foodborne and enteric bacteria. Over the past two decades, the FDA has also banned unapproved uses of cephalosporins, used to treat diseases like pneumonia, and fluoroquinolones, used in respiratory and urinary tract infections, as well as other medically important antibiotics. Additionally, antibiotics are now forbidden to be used for growth promotion (though the jury is out on how effective the rule has been). Today, thanks to FDA intervention, many over-the-counter, medically important antibiotics now require prescriptions or veterinary authorization for use.

Through the USDA, adding labels like “Raised Without Antibiotics” or “No Antibiotics Ever” to meat is a voluntary process. Producers may submit a one-time application to be reviewed by USDA inspectors, who may conduct further testing in the future.

Yet, a 2022 study by the Milken Institute found that 15 percent of “Raised Without Antibiotics” beef samples came from feedlots that tested positive for antibiotics — critics argue USDA’s oversight is lacking in this area.

This June, USDA revealed it would be taking steps to ensure greater accuracy of antibiotic-related labels on meat products. The agency now plans to conduct a sampling project in the “Raised Without Antibiotics” market. It also said its Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) will strengthen the guidelines related to the documentation companies submit when verifying animal-raising claims.

“Tyson’s change is not some high-minded reevaluation about what it is to have medically responsible use.“

Meanwhile, Tyson Foods, America’s largest beef, chicken, and pork producer, recently reported it would begin reintroducing certain antibiotics into its chicken supply chain, dropping its long-held “No Antibiotics Ever” tagline. The Wall Street Journal reported Tyson’s decision is based on data indicating that the drugs they use, called ionophores, are not considered by the World Health Organization (WHO) to be medically important for treating human illnesses. Ionophores are mainly used in poultry production to control a disease called coccidiosis.

Yet, Michael Hansen, a biologist and senior staff scientist at Consumer Reports, said in an interview that new data is becoming available that links ionophores to medically important antibiotics. “Even if [an antibiotic] is not used in human medicine, if it’s in the same family, then [scientists] are concerned about it,” he said. “Because antibiotics in the same family all work fundamentally the same way.” He continued, “When one becomes resistant, the others do too.”

Hansen said the USDA’s improvement goals are positive, spurred by consumer sentiment and increased scientific data. “People had a suspicion things were just being said, that weren’t necessarily true,” he said. Now, with increased testing and inspections, Hansen believes we’ll see greater verification of label claims.

Grocery giant Whole Foods is also facing a class-action lawsuit after an independent laboratory found antibiotic residue in “antibiotic-free” meat purchased from one of its stores. Since 1981, Whole Foods has claimed that every animal within its supply chain is raised without antibiotics.

Andrew deCoriolis, executive director of Farm Forward, an animal advocacy non-profit that first brought the lawsuit against Whole Foods, said it’s no coincidence that Tyson’s backpedaling on its antibiotic-free claims comes when the USDA is taking steps to strengthen its labeling policy. He noted that, “Tyson’s change is not some high-minded reevaluation about what it is to have medically responsible use. [It’s] purely recognition that they knew antibiotics were in their supply chain, and they weren’t going to pass a rigorous testing program.“

Scientists believe that 60 percent of known infectious diseases, as well as 75 percent of all emerging infectious diseases, are transmitted between animals and humans.

DeCoriolis added that responses like Tyson’s are a step forward, insofar as the antibiotic-free label will be meaningful to consumers. That said, he believes it’s a step back for public health and animal welfare.

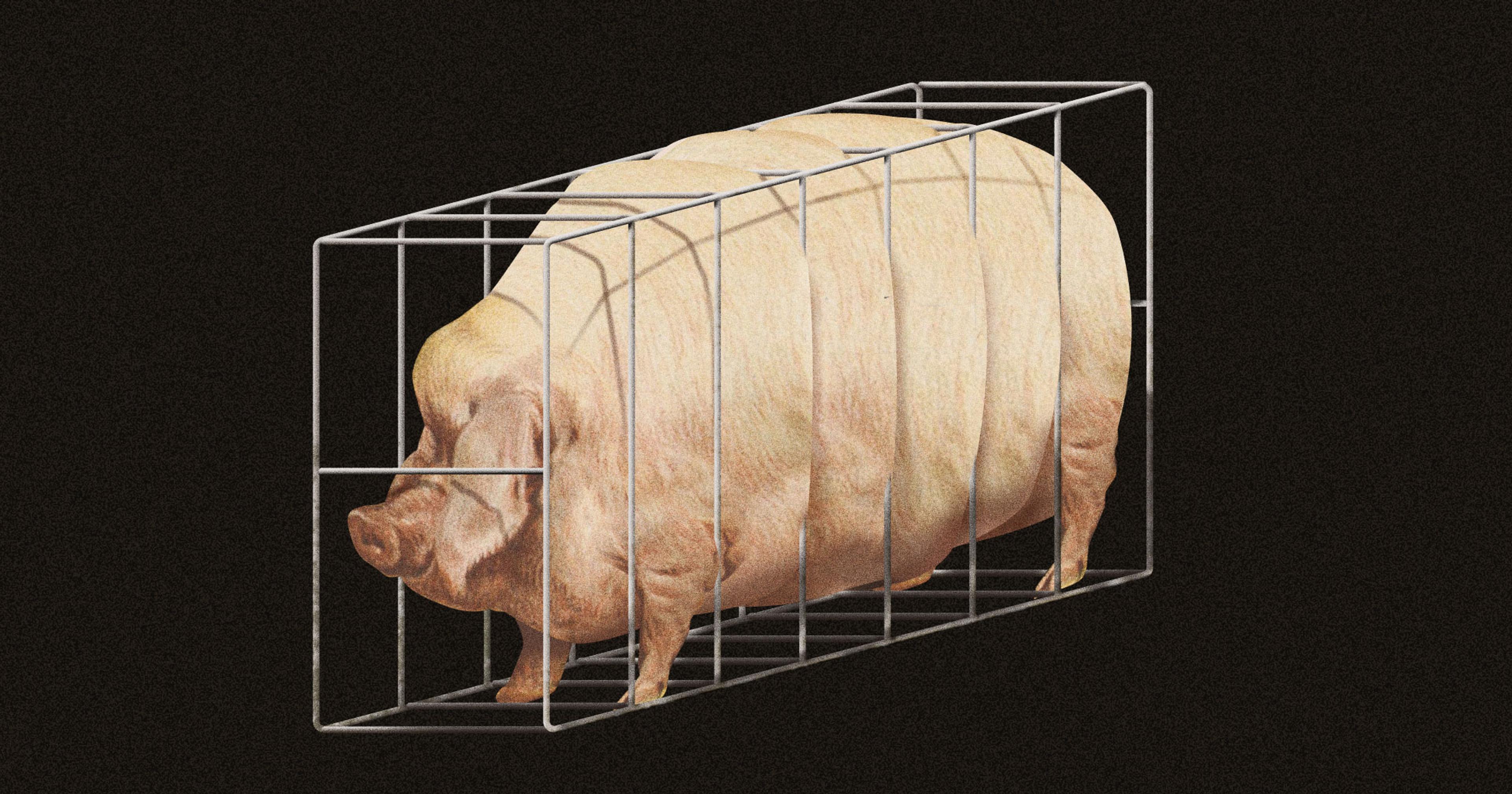

The real problem, said deCoriolis, is that companies like Tyson are unwilling to change their farming practices in the ways necessary to stop using antibiotics. This means that a significant amount of antibiotics will continue to be used, and the underlying conditions leading to the need for antibiotics — such as overcrowding, poor sanitation, and bad genetic health — will remain unaddressed.

Hansen agrees that while there have been calls for the elimination of antibiotics in meat products for decades, the fundamental problem rests within industrial meat production. “If you wanted to raise the animals in a way that minimizes the use of antibiotics, you wouldn’t be packing them together in such large numbers, or having genotypes that go from egg to harvest in 35 days.”

He continued, “Some of these chickens grow so big, and their breasts are so large, they can’t even stand up. They have leg defects. They’re packed together, so the high ammonia levels in the air cause respiratory problems, and then antibiotics are used to treat that bacteria.”

“[If] you can give the animals adequate space … that minimizes the chance they’ll be stressed out, or living in conditions that increase their risk of illness,” he said.

For decades, scientists have warned that current industrial farming practices run the risk of exposing new superbugs and sparking a long-term zoonotic pandemic. Scientists believe that 60 percent of known infectious diseases, as well as 75 percent of all emerging infectious diseases, are transmitted between animals and humans.

“Consumers have an imagination for what good animal farming should look like.”

White Oak’s Will Harris said free-range feeding allowed his animals to stay healthy without antibiotics. “When I made the first decision [to go free-range], the second decision was made for me,” said Harris, speaking on his shift to organic, open-pasture farming. “I didn’t need [antibiotics] anymore. I just turned those cows out and let them start eating grass. The freedom from antibiotics was a bonus.“

For Harris, antibiotic labeling is just one part of a larger, corrupt food cycle. As industrial farms get bigger, and food prices fall, we push costs over into other areas, said Harris, — the environment, the welfare of animals, the livelihood of farmers, and the economic productivity of rural America.

DeCoriolis echoes this sentiment, saying there should be more to consumer and producer values than just antibiotics. Despite their fallibility, he said, “Catch-all claims like ‘All-Natural’ and ‘Antibiotic-Free,’ … invoke something for consumers about the wholesomeness of the product. Consumers have an imagination for what good animal farming should look like.”

“Unfortunately,” said deCoriolis, “antibiotic-free labels are not going to ensure [good animal farming] alone. Even if the verification goes into place, and [antibiotic-free] becomes a meaningful label, that may just mean that you’ve got a chicken company that’s willing to let 30 percent of its birds die so they can market you a premium product.”

Tyson, in the Wall Street Journal, claimed its approach, “was made with the best interest of people and animals in mind.”