It’s no secret that large-animal veterinarians are in short supply across the U.S. How are we going to fix it?

Heidi Helff grew up loving animals. For many veterinarians, it’s a cliche for a reason.

As the 22-year-old grad student tells it, Helff always knew she was going to be a vet. She grew up with Labrador Retrievers and in high school shadowed a veterinarian near her home in Chester, New Hampshire, a town of about 5,000.

Like most of her class, when she enrolled in the animal science program at the University of Vermont, Helff envisioned her future taking care of small companion animals — dogs, cats, hamsters, and the like.

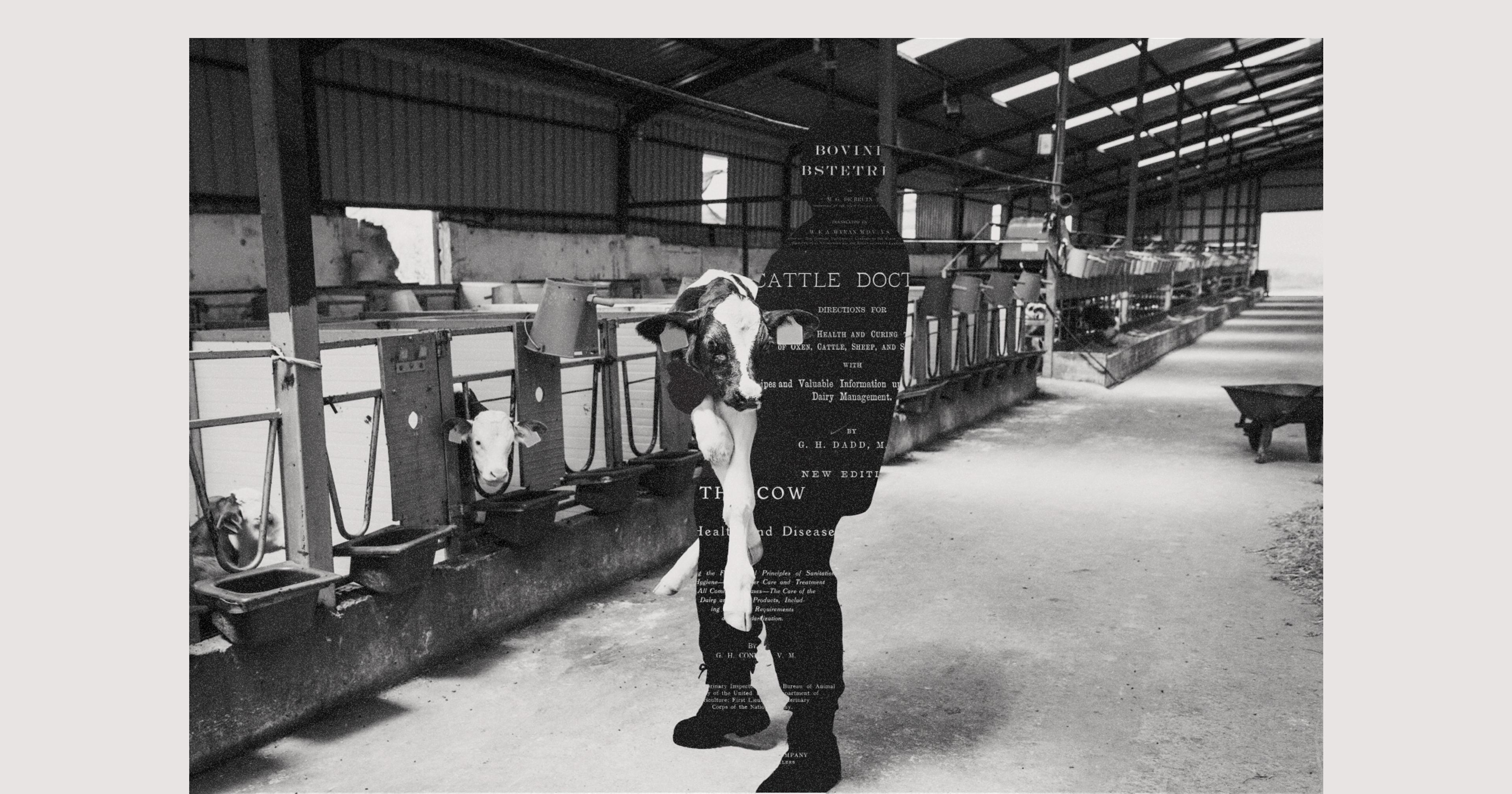

Then she met her first cow. The University of Vermont operates a working herd of dairy cattle aptly dubbed CREAM, or the Cooperative for Real Education in Agricultural Management program. Through this initiative, Helff got her first experience handling large production animals — caring for them, treating them, and waking up at 3 a.m. to milk them — and she relished it. She loved the cows’ personality and the endearing way they craved routine.

“It was truly a life-changing experience,” Helff said. “It set the path for me to want to work in food animal medicine.”

Helff is now in her first year studying veterinary medicine at St. George’s University in Grenada. The school has a working cattle program similar to CREAM, and Helff said for her capstone project she plans to study ringworm in cows and eventually move somewhere in the Western U.S. to practice.

But hers, she admitted, is a decidedly uncommon career path.

“A very small percentage of us are interested in large animal [medicine],” she said of her class.

Veterinary medicine is a difficult field — this is no secret. Speak to anyone in the industry and they will cite everything from poor mental health outcomes, high levels of student debt, long, often unpredictable hours, physical demands, difficult clients, the consolidation of the farming industry, and the general reduction in workforce as huge barriers when it comes to attracting and retaining new vets. These issues have culminated in a well-cataloged shortage of large animal veterinarians across the country.

“There’s so many different factors that there’s certainly not a single solution. It’s a big mess.”

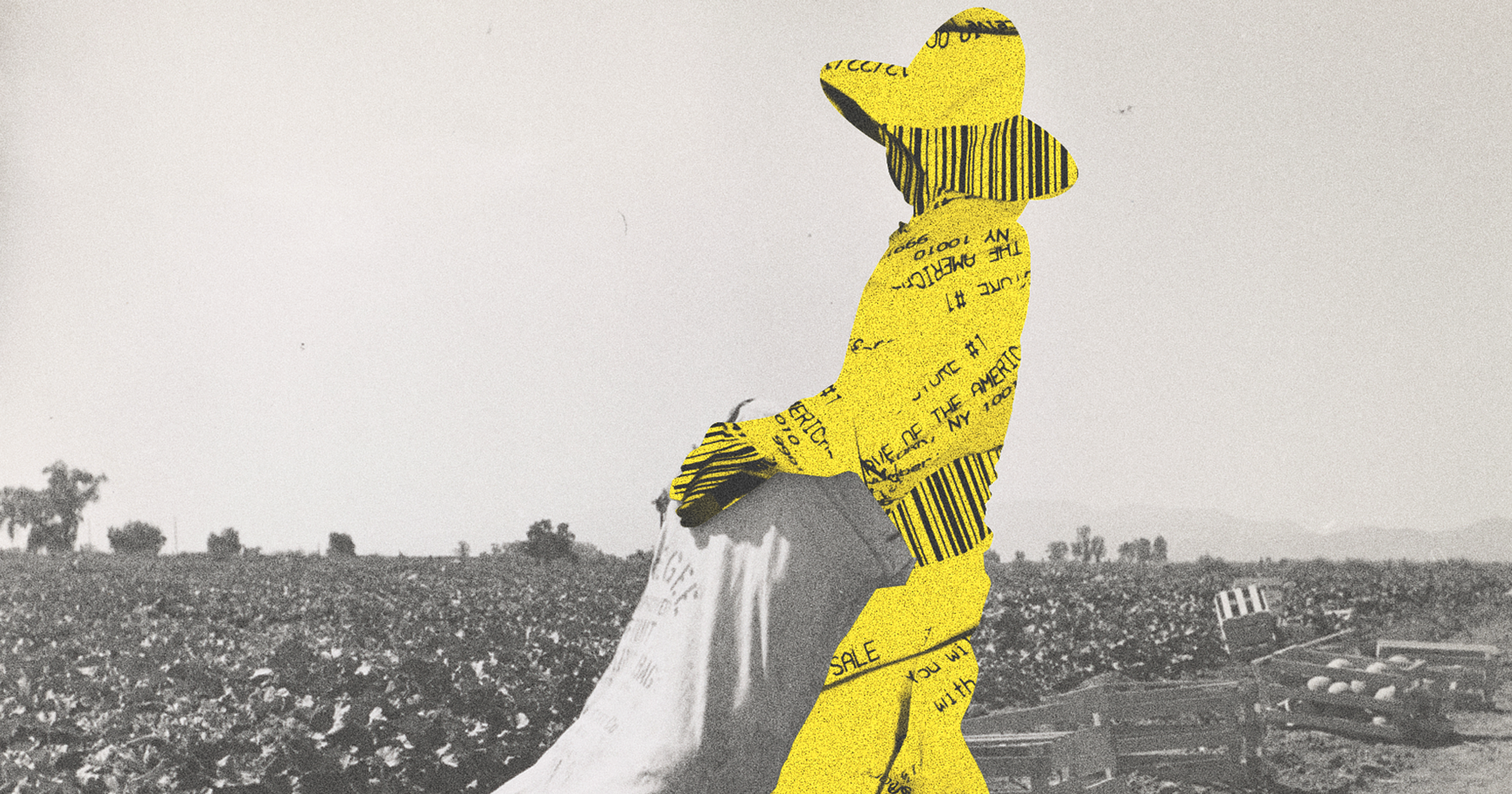

According to a 2023 Johns Hopkins report, the number of veterinarians working with livestock animals has decreased by 90% since World War II, meaning that these types of vets now account for less than 2 percent of the total veterinarian population. In addition, a recent industry survey found that more than 700 counties across all 50 states are experiencing potential large animal veterinarian shortages.

These shortages aren’t just issues for livestock farmers — they can lead to problems like unlicensed or unqualified animal care, as well as threats to food security and safety. Indeed, veterinarians represent the first — and often only — line of defense in the effort to identify and mitigate zoonotic diseases like African swine fever, salmonella, and avian flu.

However, programs like CREAM and several new initiatives are tackling the problem holistically, not only incentivizing prospective veterinarians to enter the industry, but also studying and attempting to address the social and cultural factors exacerbating the shortage.

Oklahoma State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine is piloting a new program that it hopes will help better understand the scale of the issue and offer practical solutions. Known as the Center for Rural Veterinary Medicine, the program takes a three-pronged approach: academic research, education, and training for student vets specific to rural environments (including a service component to communities lacking veterinary practices), as well as community outreach to expose young people to veterinary medicine as a career path.

“As veterinarians, we are problem solvers,” said Martin Furr, assistant dean of clinical programs at OSU’s College of Veterinary Medicine. “We need to approach this problem of the rural veterinary shortage in the same way: a scholarly approach, understanding the problems, the dynamics, what is going on, and then developing a strategy to fix it.”

While the program is still in its infancy, Furr said it has already generated strong interest from both students and local communities.

“I would hope that this would be a model for how other universities start to think about the problem and develop their own approaches so we get more people working on this issue,” he said.

“You work 10 days out of a 14-day period and you’re on-call and you’re putting prolapses in in negative degree weather and chasing horse colics around. It’s kind of a hard sell.”

Part of the problem is that despite their importance, many rural veterinarians say the current landscape of the industry has made their careers unsustainable. Sarah Wagner, who spent five years as a practicing large animal veterinarian in rural Virginia before transitioning into the world of academia, said that the rural vet shortage mirrors other industries’ longstanding struggles to draw newcomers to the agrarian reaches of the country.

“My boss was a good mentor, but I was very lonely,” Wagner said of her experience. “I was never part of the community.”

As the assistant dean and a professor of pharmacology at Texas Tech University’s School of Veterinary Medicine, Wagner has spent a lot of time thinking about the plethora of issues currently plaguing her field. She noted that as women make up the vast majority of veterinarians in the U.S., institutional problems like sexism — particularly in rural areas — and the gender pay gap have become increasingly prevalent.

“There’s so many different factors that there’s certainly not a single solution,” Wagner said. “It’s a big mess.”

Stephen Wadsworth was Helff’s mentor through the CREAM program at UVM. Wadsworth, who has spent more than 40 years as a practicing veterinarian in northern Vermont, said the landscape of both farming and veterinary medicine has changed “radically” since he first entered the field.

While the number of dairy cows and production levels have remained relatively constant, the state has seen the number of farms cut in half since 2012. Consolidation means operations are more geographically spread, leading to more “windshield time” for vets. And without a critical mass of farms in rural communities, practices in those areas have an increasingly difficult time making ends meet, which in turn affects the salary they can offer recent graduates.

“It’s such a multifaceted problem that the solutions are going to have to be similarly complicated and nuanced,” Wadsworth said.

“To leave their comfort of suburban or urban culture and move out to a little country town out in some rural area, that can be intimidating.”

Industry organizations like the American Association of Bovine Practitioners (AABP) and American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) have attempted to alleviate the shortage through approaches like student debt relief. According to AVMA data collected in 2023, veterinary students graduate with an average of more than $150,000 in student loan debt. Started in 2010, the organization’s Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program, which repays up to $75,000 of debt for qualified individuals, has placed roughly 800 vets into areas with veterinary shortages.

“It’s not the answer, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction,” Wadsworth said of the program.

Earl Brady, who owns a large animal practice in northern Vermont, said he’s had success using the student debt relief program. But even so, the economics of rural operations are extremely difficult to balance.

“When you’re in school and you have $300,000 of student debt, you have the option to go work for a small animal clinic and make $120,000 working four days a week with no on-call,” he said. “Or you go to rural Vermont and start at maybe $85,000 and work 10 days out of a 14-day period and you’re on-call and you’re putting prolapses in in negative degree weather and chasing horse colics around. It’s kind of a hard sell.”

Beyond the economic considerations, current and former veterinarians stressed the importance of community and human connection when it comes to both attracting and retaining workforce, particularly in rural areas. Less quantifiable considerations like mentorship and peer relationships can play a pivotal role in helping combat the rural veterinarian shortage, they said.

Indeed, a survey of recent veterinary medicine graduates, published by the AABP in 2022, found that peer support and mentorship were key in offsetting the common feelings of “isolation or loneliness often experienced in rural communities where other similarly aged professionals are scarce.”

“You’re on the road or doing work alone, you’re not in an office with colleagues or friends,” Brady said. “It’s so important to have your thing or foundation that keeps you human outside of work. For some it’s church, for some it’s 4H club, or skiing, ice fishing, that sort of thing. Finding that community makes it a sustainable thing.”

“To leave the comfort of suburban or urban culture and move out to a little country town out in some rural area, that can be intimidating,” Wadsworth added. “Many of these young people need some guidance and mentoring and somebody with wisdom who can guide them through the minefield of life.”

Since taking over the practice in early 2022, Brady has nearly doubled the size of his team, hiring three recent veterinary school graduates and expanding the coverage area by 50 miles. He said he’s found some success searching for candidates that have a prior connection to the state, but even so he worries constantly about turnover.

“We’re trying to figure out how to accommodate the clients and not burn out the [staff],” Brady said. “I’ve got to figure out strategies to keep people on board.”