Forward-thinking ranchers are embracing virtual fencing technology for business reasons. Across this technology’s invisible barrier, wildlife waits with interest.

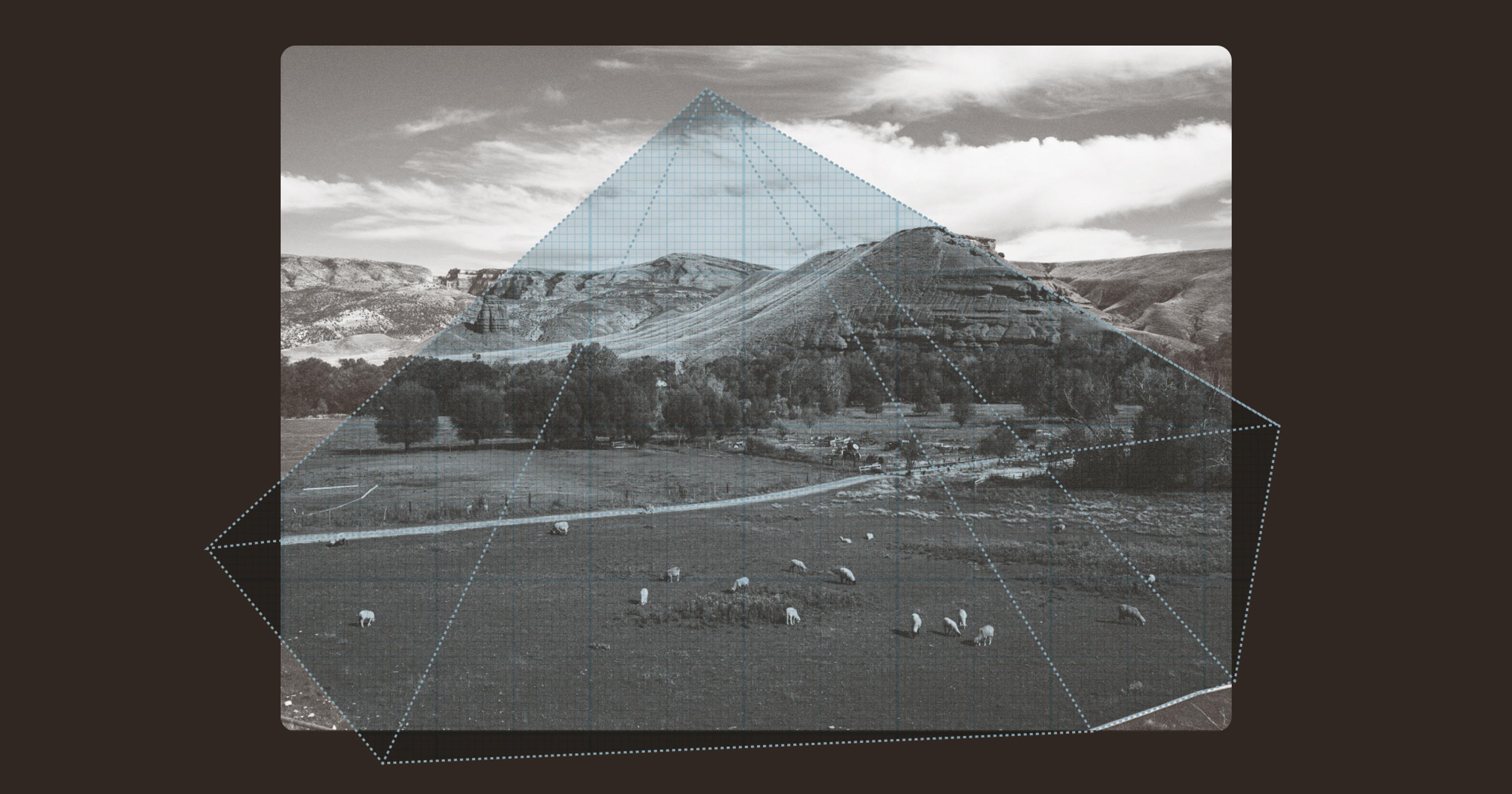

As Colorado cattle rancher Gayel Alexander greets each day from her neat and orderly home porch, she relishes its contrast to the rugged landscape surrounding Ja Quidi Ranch. Her panoramic view displays a living ecosystem, from the constrained harshness of the ranch’s summer pastures to the deep canyons of her winter grazing allotments. This ecosystem holds dear a structure of both wild and domesticated life.

Scattered throughout 41,000 Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Forest Service, and privately owned high-desert acres, her 225 cow-calf pairs graze alongside deer, antelope, bears, mountain lions, and the most dominant of local wildlife: elk.

The crux of Alexander’s business is protecting her herd, keeping them safe and content while providing an income. Cattle operations have for centuries relied on physical fence lines to manage this fragile balance between the domesticated and the wild, but the Ja Quidi Ranch is turning to technology, specifically virtual fencing, to maintain order. But there’s an emerging side benefit that Alexander and other conservationist ranchers are noticing: It strengthens the wildlife and natural habitats that share her lands.

Changing Control Patterns

Over recent decades, permanent fence posts and wires controlled Alexander’s cattle’s grazing habits, but the herds of elk calling her land home have had a significant say in the strength of this control.

“We can spend weeks fixing an old fence and building a new one and a single bad winter makes it look like we haven’t done anything,” Alexander said. “When 200 to 400 elk come off the high country moving in a mob as wide as a house, they tear up miles in the blink of an eye.”

With these chaotic scenes driving her thought process, Alexander changed how she controlled her cattle.

In May 2024, thanks in part to a USDA-related grant, she began using Vence virtual fencing technology to reduce her costs and slash the time and labor set aside to monitor, repair, and replace her fences.

“We can spend weeks fixing an old fence and building a new one and a single bad winter makes it look like we haven’t done anything.”

Virtual fencing uses software to draw perimeter pasture lines on a digital map. These coordinates are transmitted via radio towers to GPS-enabled collars fitted with radio antennas. When cows wearing the collars approach the invisible lines, they first receive an audible warning to keep their distance. If ignored, a weak electric shock moves the animal back into the desired coordinates.

Alexander’s initial interest in the tech was money-related.

“Yes, primarily my reasons were focused on my cattle,” she said. “I wanted to save money on infrastructure, improve my range management, and build up intensive grazing practices to increase my herd numbers.”

But the benefits didn’t stop there.

Bringing Wildlife Behavior Into the Equation

Wildlife care ultimately became a vital reason for Alexander’s interest.

“The elk and deer travel the same route every season like clockwork,” she said. “I knew they would break through fences, and of course, some would get hurt or worse. My life is about caring for animals. I didn’t want to passively accept this kind of thing.”

Karie Decker, director of wildlife and habitat at the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation (RMEF), a Montana-based conservation and pro-hunting organization, sympathizes with Alexander’s view. Decker says that research examining the impact of fence-line-dotted landscapes on big game species behavior is ongoing.

“It’s true big herds of elk moving in a hurry take them out,” Decker said. “Injuries and deaths are a bigger deal for deer and pronghorn as they tend to get tangled up easier and more frequently, but we have many records of elk, especially calves, getting hung up, and breaking legs as they try to get free. Elk bulls’ giant antlers become an even bigger risk in the fall and winter.”

She explained that RMEF research confirms that elk avoid heavily fenced areas. Pronghorn antelope and deer will also be redirected from high to low-quality forage regions. “This behavioral shift influences their migration and breeding, plus hurts their ability to get food, especially during the hardships of winter.”

Physical Fences Promote Genetic Vulnerability

On top of these issues, Decker believes too many permanent fences harm elk’s genetic maintenance and improvement.

“Young bulls need to separate from their herds to wander; it’s key for genetic variability and keeping bloodlines healthy,” she said. “If they face significant barriers, roadways, and large obstructions, this wandering isn’t successful. Genetic improvement takes a hit.”

Studies focusing on pronghorn antelope also confirm wire and posts alter their migratory paths. As antelopes are built for speed and not for jumping, they will often follow fences for miles, wasting the energy necessary for breeding.

Densities, Time Budgeting, and Travel Data

The University of Wyoming Migration Initiative has also documented ungulate behavior changes due to cattle fences. “Density is a big deal,” said Jerod Merkle, Knobloch Professor of Migration, Ecology, and Conservation. “We have evidence proving animals don’t spend much time around areas with a high fence density.”

Matt Barnes, a Colorado-based rangeland scientist and wildlife conservationist, believes wildlife must move without impediment, largely for seasonal migrations but also between plant communities. “Physical obstacles are a barrier to this movement and barriers are rarely a good thing,” he said.

During the last decade, U.S.-led research has doubled down on the importance of migration for elk, deer, and pronghorn antelope. Attached radio collars are proving big game moves farther than anyone initially thought.

“We’re seeing the extent of their travels,” Barnes said. “We’ve confirmed physical fences and infrastructure create pinch points to slow migrations. This is especially noticeable in the more arid West where deer and elk naturally follow the greening up of the grasses and plant life. It stands to reason virtual fencing would provide a much greater opportunity to roam freely wherever their natural instincts take them.”

He explained that physical fences interrupt migratory paths not only from winter to summer range but also through the habitat itself. “We simply don’t know to what level this reduces numbers or weakens species since fences are a barrier but not an absolute barrier,” Barnes said. “It’s hard to measure without more research.”

Ecosystem Gains

In 2022, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), a global environmental nonprofit, began a 5-year research project on Kansas, New Mexico, and Colorado ranches examining the relationship between virtual fencing and the environment.

“Partway in, we’re finding it’s a game changer for land managers of all stripes,” said TNC deputy director of the North American Regenerative Grazing Lands Program, William Burnidge. “It reaches wildlife habitat, water resource management, and business outcomes.”

Burnidge explains the benefits for biodiversity and wildlife include the removal of physical obstructions that injure or kill birds during flight. There are also indirect benefits that improve range conditions and habitat, aid adaptation to drought, deal with fire after-effects, and even integrate prescribed burning.

The TNC trials also investigate virtual fencing’s impacts on plant communities and their productivity, ecological processes, biological activities, and the cycles above and below ground.

“Partway in, we’re finding it’s a game changer for land managers of all stripes.”

Riparian areas are managed to promote greater health, and thicker, denser vegetation, particularly grasses and forbs. “We’re seeing definite signs of early vegetative response and a reduction in erosion and other aspects impairing water quality,” Burnidge said.

Burnidge said they are in the early days of accurately assessing soil health and carbon sequestration, but emphasized its importance as global grasslands hold approximately 20% of the planet’s carbon stocks.

“The worst thing we can do for the climate is convert grasslands to other land uses,” he said. “Breaking grassland up releases perhaps as much as 50% of the carbon from the soil. If technology can improve business and quality of life for cattle producers, it reduces the risk of these lands being converted to corn or other uses.”

Burnidge stressed the key to virtual fencing technology contributions lies in the recovery that plants and grasses gain during and after grazing events. “Virtual fences deliver a path forward by providing more valuable growing seasons and rest periods.”

Out With the Old

Tracing invisible lines on a computer to contain cattle is intriguing, but nothing substantial changes until the old obstacles are removed. In the short term, ranchers are shying away from rolling up wire as the policy issues around what’s legal, what’s a right of way, or what a neighbor-to-neighbor boundary looks like are hammered out.

Back overlooking her Colorado landscape, Gayel Alexander is hopeful the U.S. Forest Service will give her the nod to clean up the old wire on her parcels, leaving only the wooden posts so elk don’t tear up miles of fence or die in the process.

“Fences are a wonderful tool, but elk can’t help how they behave, migrating in the same corridors every year,” she said. “I know some are getting hurt and dying when they come through … This technology is still in the early ‘working out the kinks’ stage, but we’re hoping for a positive outcome for everyone on both sides of the real and the invisible.”