Years after an Upstate farm family started spreading biosolids on their land, local wells started registering high PFAS levels. Things got ugly.

Eva Turner anticipated the usual five or six people to attend Cameron, New York’s, March 2024 board meeting. At least 20 showed, filling all the plastic-backed folding chairs in the tight, low-ceilinged town hall. The reason for the surge, mused Turner, a retired mechanic for Philips lighting company, was the vote to extend the town’s year-old moratorium on sludge, the sewage that’s left over after the wastewater treatment process. The vote was first up on the agenda, and representatives from Casella Waste Systems — top sludge distributors in these hilly west-state dairy lands — were expected to attend.

For decades, Cameron residents have been fighting the spread of sewage sludge on surrounding farmland, which they say has been contaminating their water. Last year’s moratorium was hard-won and residents were concerned that its hold was tenuous; Cameronians had packed the hall, prepared to fight on, if it seemed the board might allow Casella to pick up the practice again.

As it happened, the Casella reps were absent and the vote was delayed on a technicality. But Turner, her community compatriots, and Steuben County neighbors from the next-door towns of Bath (which passed a moratorium on sludge then changed its mind) and Thurston (which banned sludge last October and got sued to reverse it) spent an hour venting their frustrations.

Longtime Cameron resident Wayne Wells called Steuben County an “industrial sacrifice zone.” Steven Stewart, a retired farmer from Bath, said he was spending $700 to test his wells because he feared the effects of sludge that were spread on fields adjacent to his land. Cameron native Tim Hargrave, whose creek contains over 24 parts per trillion (ppt) of PFAS, brought up Dickson farm, which spread sludge on some 2,000 acres planted with corn, soy, and hay. He said his land’s value had plummeted.

Environmental Working Group sets a maximum safe limit for toxic “forever” per- and polyfluoroalkyl — PFAS— chemicals in drinking water of 1 ppt. Meanwhile U.S Environmental Protection Agency has just set limits in drinking water for several of 15,000 PFAS chemicals, of between 4 ppt and 10 ppt, while noting that for at least two of these chemicals there is no safe level of exposure. “Put the sludge next to your property to contaminate your [water] and see if you feel differently,” Hargrave said to a board member who’d just equated sludge bans with communism.

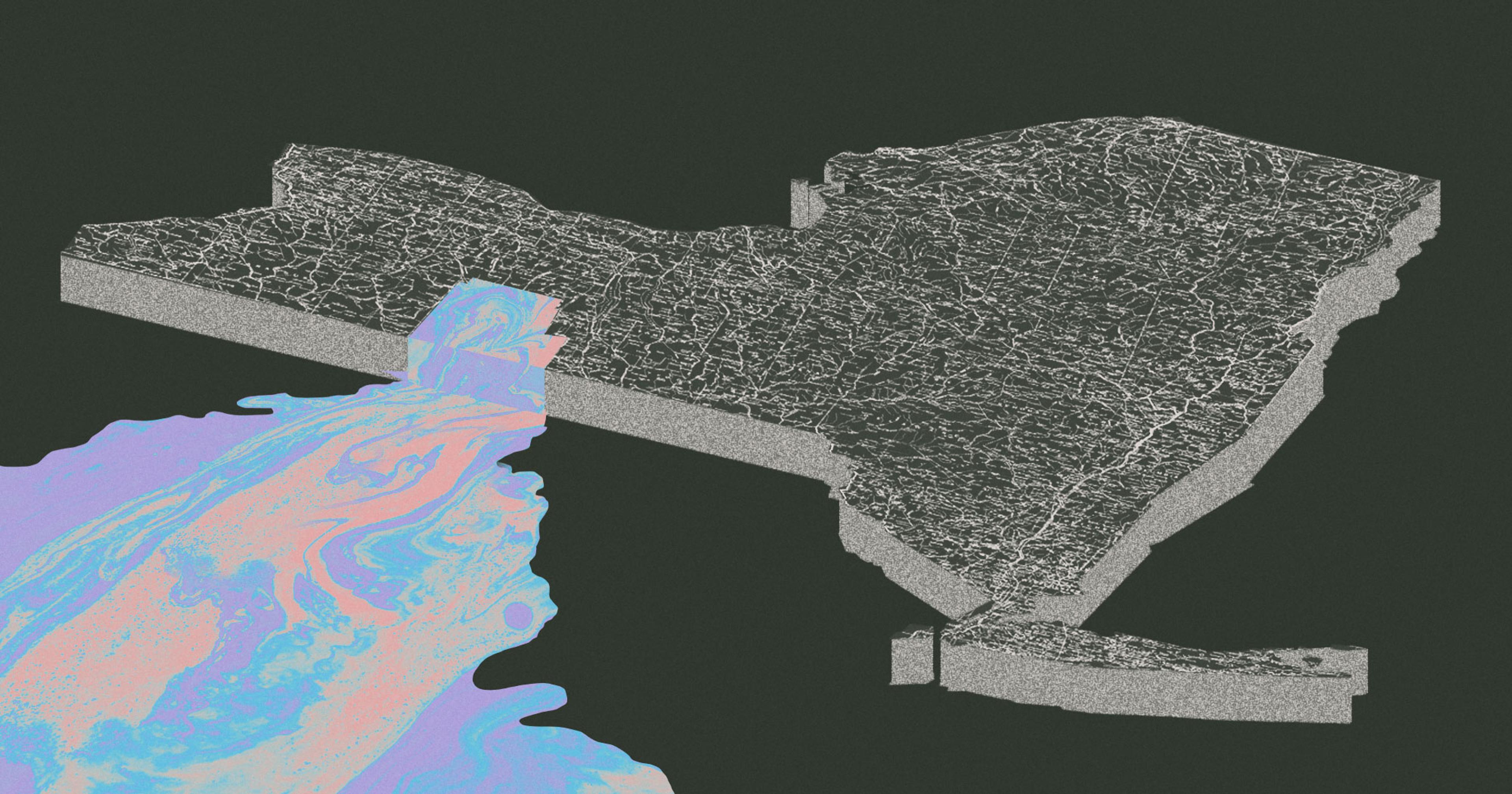

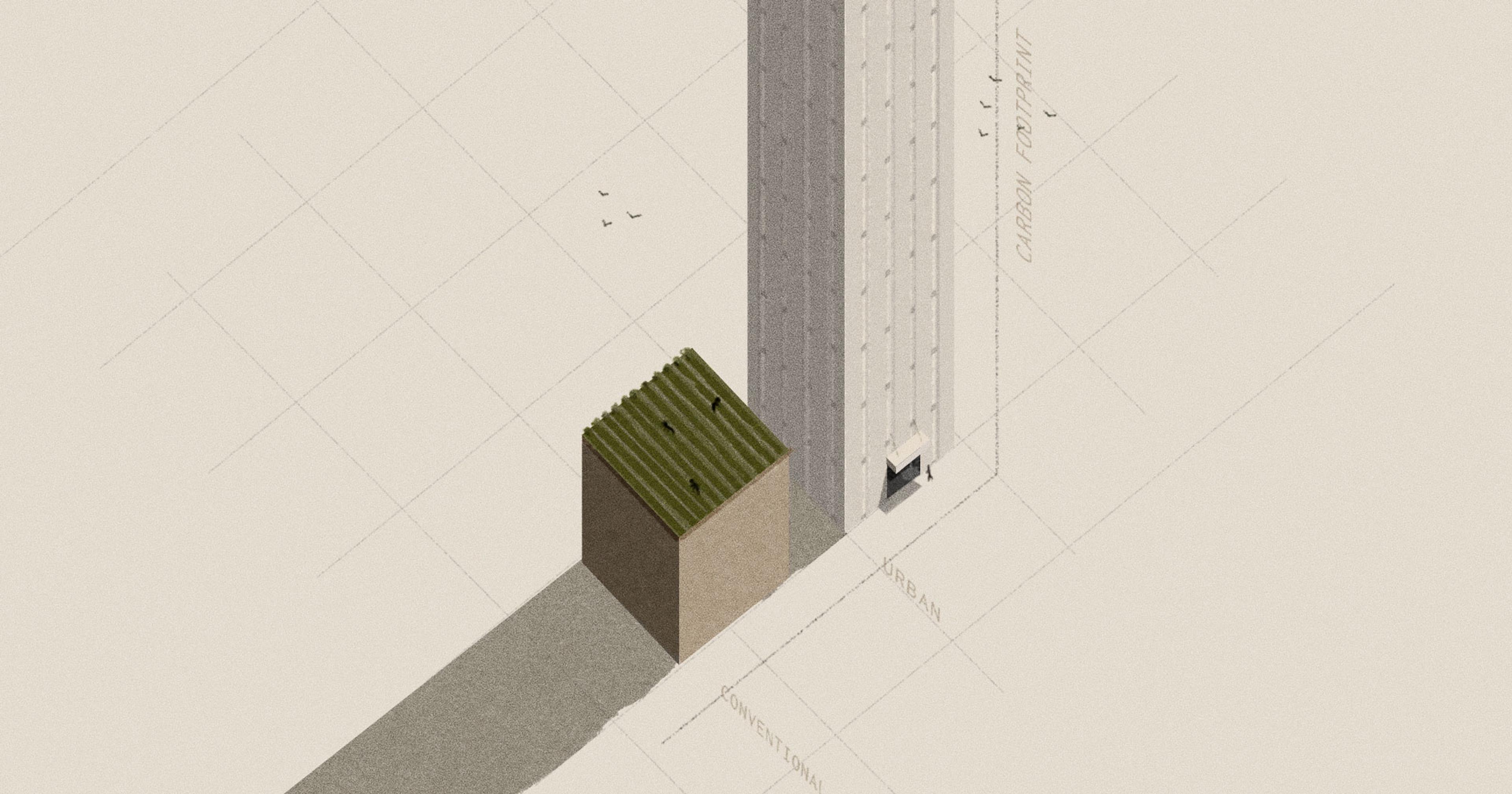

Since 2016, more than 19 billion tons of sewage sludge — more politely known as biosolids — have been spread on 20 million acres of agricultural land across the U.S., according to EWG. EPA touts them as containing nutrients beneficial to agricultural lands, despite sludge’s known potential to contaminate soil and water; there are no limits for PFAS in biosolids. Maine banned sludge in 2022 after finding high levels of PFAS in farmers’ milk, beef, and crop-growing soils; PFAS-affected farmers in Texas, Michigan, and South Carolina are raising the alarm all over again.

But to the incredulity of Steuben County residents, New York appears to be ignoring evidence of the pending environmental, public health, and food security catastrophe presented by contaminated biosolids. The state plans to more than double the amount of land-spread sludge by 2050 — despite the fact that “It’s completely not protective of human health or water quality to spread sewage sludge anywhere,” said Laura Orlando, senior scientist at climate impact nonprofit Just Zero. Even more of it could be headed Steuben County’s way, should the towns’ rules falter and Casella manages to enact a plan to truck in sludge from Long Island.

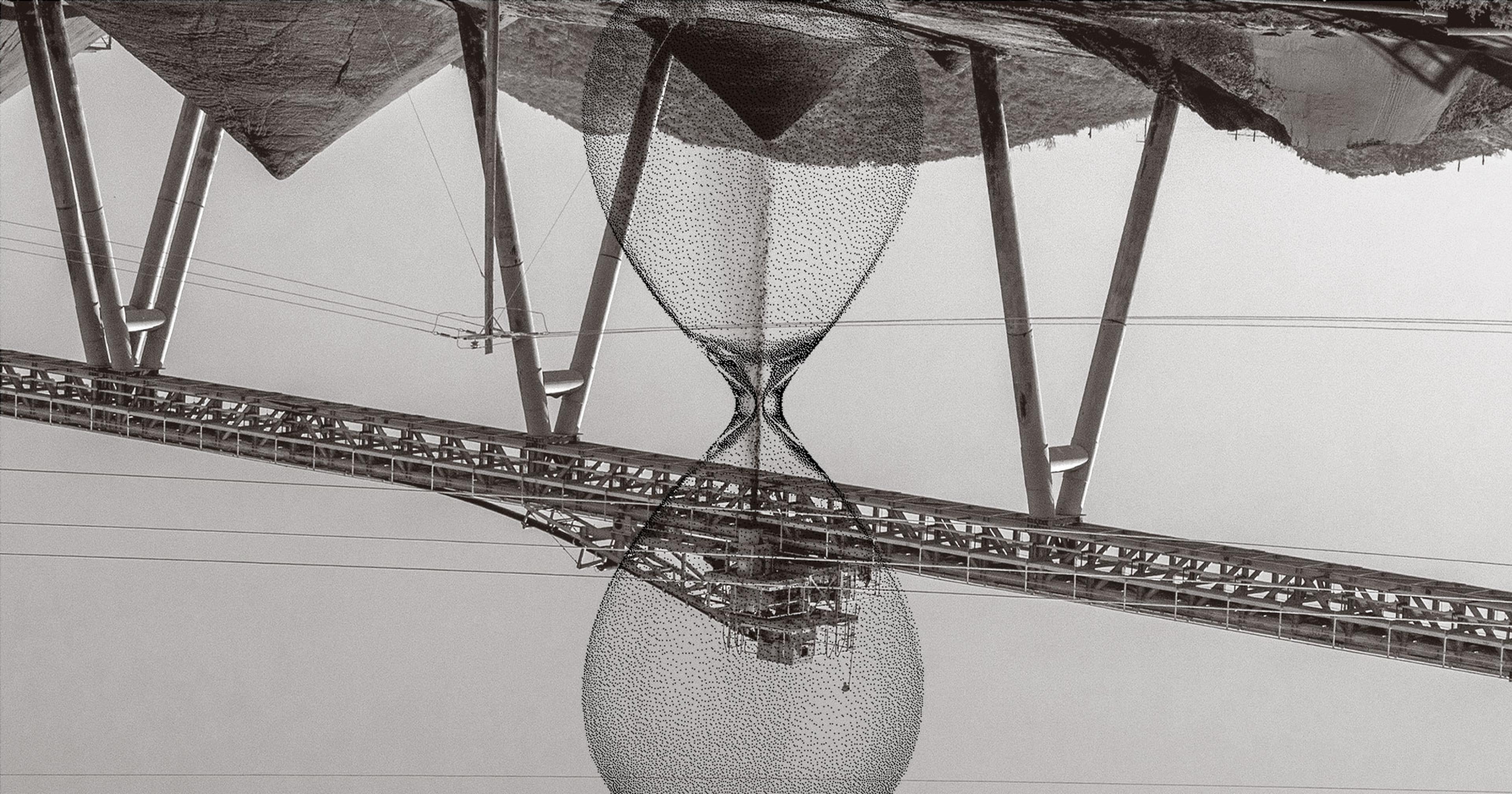

Sewage sludge is what’s left over after municipal treatment plants clean up the wastewater flowing to them from household bathrooms and kitchens, local industries, and the sewer system. Cleaned water is released back into waterways. The residual sludgy material may be incinerated or pressed into pellets and marketed as lawn fertilizer.

Alternately, it’s picked up by a waste management company like Casella that may landfill it, sell it, or give it away to farmers. Since EPA and state conservation offices continue to extol it as an amendment for crop and dairy fields, often “a farmer will approach the state and say, ‘Where can I get this stuff?’” explained Orlando. “It’s a cheap disposal practice.” USDA organic standards, though, have banned sludge on organic farms since the mid-‘90s, for its potential manure ash content — a precautionary measure that now seems both quaint and prescient.

Lela Nargi

·A yard sign in Thurston

Federal rules governing sludge were written before much thought was given to PFAS. But EPA revisits standards every two years to figure out if there are any new contaminants it needs to regulate. Nevertheless, only nine heavy metals are on the list, said Murray McBride, emeritus professor of soil chemistry at Cornell University. Pharmaceuticals, microplastics, PCBs, surfactants, and high levels of phosphorous that might induce micronutrient deficiencies in crops, also appear —and are allowable — in sludge.

The citizens of Steuben County, though, are most alarmed by PFAS, which they know is linked to thyroid, testicular, and kidney cancers, and developmental delays and behavioral changes in children. To help them understand the extent of their problem, last year the local Sierra Club chapter sponsored water testing of 83 of their wells and other water bodies. PFAS contamination was nine times higher adjacent to fields where sludge was spread. One well, on Bonny Hill in Thurston, contained a whopping 82 ppt of PFAS.

Adam Nordell, one of four farmers forced out of business in Maine because of legacy PFAS on his land, said that many producers he knew felt similarly alarmed —as well as duped. “Farmers were told [sludge] is safe, that you’re foolish not to accept it,” he said. “Often contractors did the application so the farm didn’t have to — there’s no wear and tear on the farmers’ equipment, there’s no tax on the farmers’ time, and in some cases the contractors built access roads to handle the heavy equipment, actually investing in farm infrastructure. In hindsight, if it looked too good to be true it probably was too good to be true.”

“Farmers were told sludge is safe, that you’re foolish not to accept it ... In hindsight, if it looked too good to be true it probably was too good to be true.”

Bonny Hill is home base for Casella’s local operation, and the former site of a milking barn for a local farming family, the Dicksons. This family ran a multi-generational dairy operation that moved into sludge spreading some 25 years ago, sold and leased that part of its operation to Casella in 2022, and now raises livestock feed. Their operation was a co-plaintiff with Casella in the lawsuit against the Thurston ban, which they said violated New York’s Right to Farm law that permits the practice. (As of this writing, the case has been discontinued but according to environmental law nonprofit Earthjustice, which represents the town, a new, similar challenge could eventually be filed.)

Referencing the lawsuit, a Casella spokesperson said the company would not spread sludge on Dickson farmland until “all regulatory issues have been resolved,” but pushed back on the notion that PFAS in biosolids were a health concern. Dangers from the chemicals, they wrote, “more likely exist at the beginning of the product life cycle rather than at the end of the waste stream.” (The Dicksons could not be reached for comment.)

Lela Nargi

·Cameron residents Tim Hargrave and Eva Turner

The day after the Cameron board meeting, a dozen neighbors gathered up the hill from Casella’s office. They were armed with water quality data; maps showing fields permitted for sludge spreading; documents they’d procured through FOIL requests; and articles that tracked their sludge fight back to the ‘80s. They tapped long memories, tracing their erosion of trust in the Dicksons, who they’ve known their whole lives and who they believe overlooked their concerns about the dangers of sludge. “They were respected people in the neighborhood; my grandfather was friends with their grandfather,” said Mary Borhman, who alleged they violated a verbal agreement not to spread sludge on fields she leased them.

Neighbors also expressed a deep frustration with New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), which they accuse of both dismissing their concerns about PFAS and ignoring sludge violations (e.g., spreading it on unpermitted land or failing to plant buffer zones to keep it out of streams and creeks). “Their method of operation is just, brush little people off to the side and keep pushing us off,” said Hargrave.

“DEC recognizes the potential for PFAS to re-enter the environment and negatively impact natural resources and public health with the land spreading of biosolids that may contain excessive levels of PFAS,” wrote a spokesperson in an email, while referring to biosolids as “nutrient-rich organic materials.” The agency has “enacted a policy to specifically address biosolid use that includes sampling requirements for biosolids recycled in New York State.”

In an email, Orlando called DEC’s stance an “anti-science and anti-public health approach to biosolids management;” if EPA has said there’s no safe level of certain PFAS in drinking water, how is it that PFAS in sludge — which can leach into drinking water — is not a comparable health threat?

“Their method of operation is just, brush little people off to the side and keep pushing us off.”

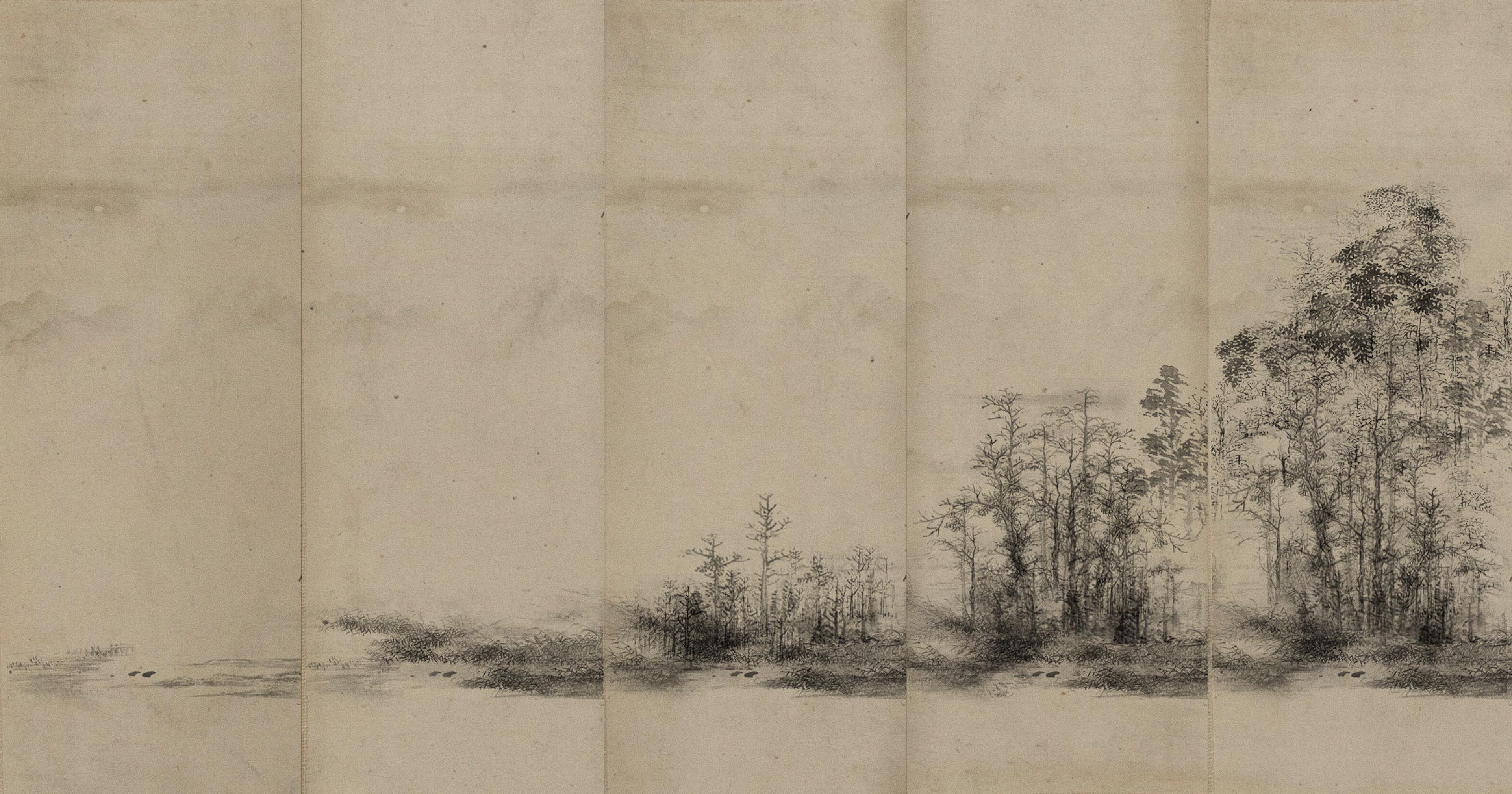

Steuben County residents are keeping an ever-growing tally of the ways sludge has upended their lives. A few people have installed costly filtration systems for their wells, although most opt to buy bottled water. Everyone fears that contaminated wells mean they’ll never be able to sell their homes.

Borhman and another neighbor, Jamie Quick, recalled the pigs and cows and chickens most families around here once kept to feed growing families — part of a heritage Hargrave revived 10 years ago, fixing up his Cameron property to raise beef cattle. Although his wells and therefore his cattle water supply contain no PFAS, he said the butcher he intended to sell to “is not willing to take the risk” on the meat, since his property abuts sludged fields. And Hargrave expressed concern that wild deer were likely contaminated with PFAS, too. “That’s a huge impact for the local people that live here if we can’t hunt and consume this meat,” he said.

Much to the relief of Cameron residents, the town board voted to extend the sludge moratorium another year on April 10. But their long fight against it has taken an emotional toll. People are reconsidering family deaths and whether PFAS played a role in them; Eva Turner can rattle off every house in her town that’s been hit by cancer. Leslie Smith will tearfully recount that the pond he’d built for his grandchildren to fish and swim in is off-limits due to high levels of PFAS.

And Wayne Wells worries that the moratoria and bans won’t hold. An 80-year-old Vietnam veteran who should have retired years ago, he was contemplating acts of civil disobedience. After 40 years of fighting the sludge, “I think that might be the only way to stop it,” he said.

Reporting for this piece was supported by a media fellowship from the Nova Institute for Health.