Mycoremediation — the use of fungi to degrade contaminants — shows great promise, but still has a long way to go.

Fifteen years ago, Danielle Stevenson, former urban agriculture coordinator in Victoria, British Columbia, set out to help the city’s public schools establish vegetable gardens. It was an exciting project, but a major roadblock kept rearing its head: When she tested the soil on prospective garden plots, she would find hazardous levels of lead and other metals, rendering it unsafe to grow food. The projects would grind to a halt.

“Nobody knew what to do about it,” said Stevenson, who grew up living and working on farms.

Instead of getting discouraged, the soil toxicity problem piqued Stevenson’s curiosity. Ultimately, it led her to work full-time on developing ecologically regenerative methods of cleaning up contaminated soil and water. Now an environmental toxicologist and mycologist, some of her favorite tools are fungi.

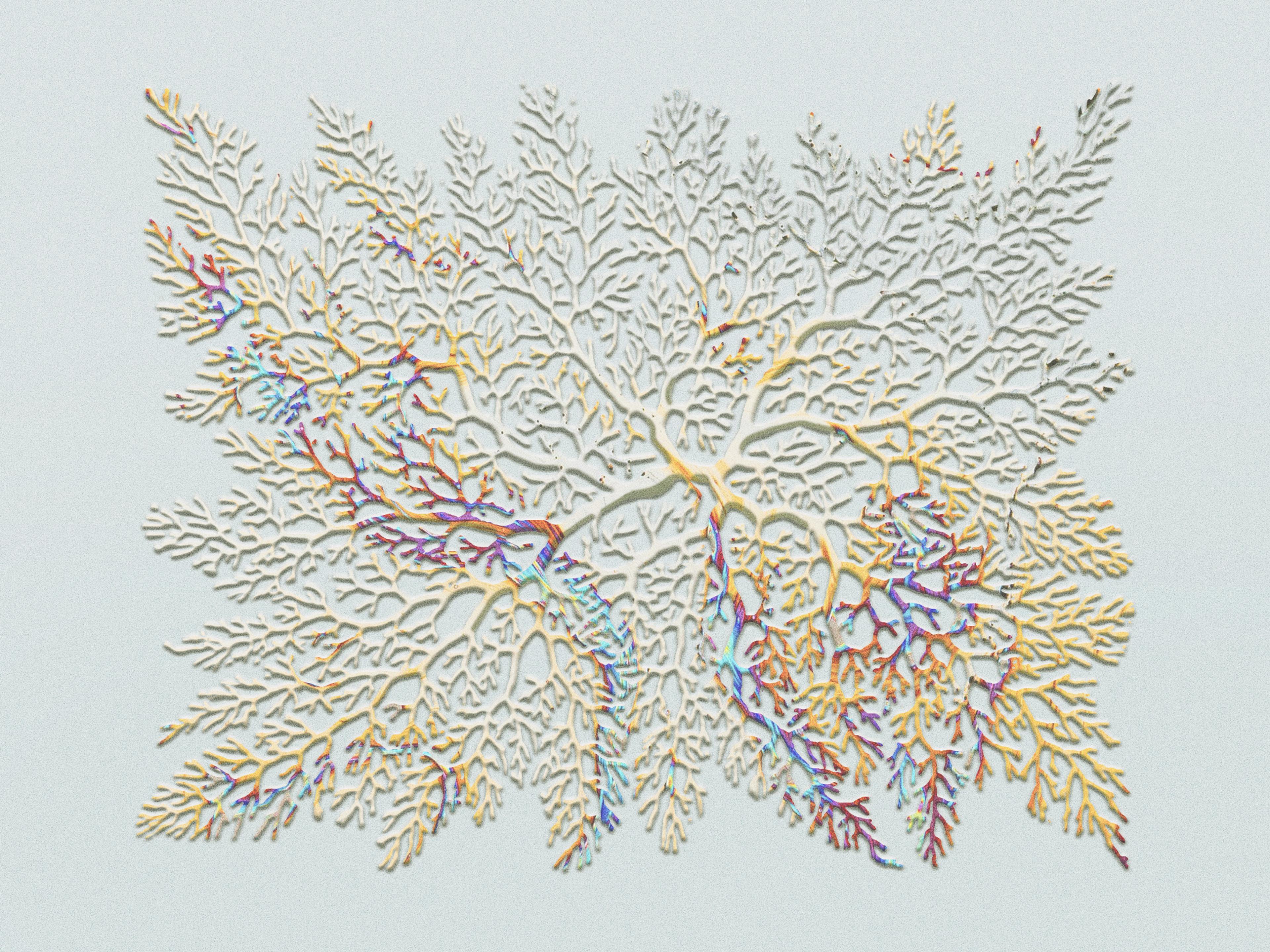

Stevenson is an expert in the small but growing field of mycoremediation, or the use of mycelium to restore the health of soil or water. Certain fungi can essentially “eat” toxins; their mycelium produce enzymes that degrade some plastics, petroleum, and heavy metals. Mycelium are an underground network of fungal strands, and the potential of this fungal root system is already being realized in leather and plastic alternatives, building materials, and meat substitutes.

While mushrooms have enjoyed a moment in the spotlight in recent years thanks to innovations like these, mycoremediation still has a long way to go. There may be great potential in applying mycoremediation to agricultural settings, but there are still major impediments to applying the method at scale.

“There’s a lot of talk about the potential of fungi, but a lot of the studies have been done in a lab and on a very small scale,” said Stevenson.

One of those promising smaller-scale projects took place in Marathon County, Wisconsin, in 2021, led by the county’s solid waste department. Alex Thomas, a compost and hazardous waste specialist, was contacted by a machine shop that had accidentally spilled coolant all over its gravel parking lot and was looking for help with cleanup. Thomas and his colleagues had been waiting for an opportunity to experiment with mycoremediation, and the oily parking lot was their chance.

A local mushroom farmer excited about mycoremediation, Jerome Segura, agreed to donate blue and pink oyster mushroom blocks that had already been harvested to the project. The blocks, which contain the organic substance mushrooms are grown in and the mycelium left behind after the fruiting bodies are harvested, are a waste byproduct from mushroom farming. The team broke up the blocks over oily soil that had been removed from the parking lot and put into three plots: one with pink oyster mushrooms, one with blue, and one without mushrooms. They were thrilled to find in a 96% reduction in oil waste in the blue plot, and 60% reduction in the pink.

“Polymers are thick and they have to be decomposed to smaller pieces, and fungi are specialists for doing that.“

“It tells us that this is a pretty easy field method, that with a couple more verifications, and a systematic approach can be a kind of an approachable in situ treatment, or at the very least, a very cost-effective treatment for hydrocarbon spills,” said Thomas. The experiment involved minimal interventions on the part of the team: They just broke up the mushroom blocks over the oily soil and watered them a few times, and let the mycelium do their thing.

“This is a good case study of where we can use existing waste to solve existing problems, and give it a second life and second use,” said Thomas. “Mycoremediation is really exciting from that aspect.”

Segura worked on other projects with the county waste department, including a promising experiment that demonstrated the potential for mycelium to reduce the presence of PFAS in water. But Segura says there is often a failure to reproduce such studies or publish their findings, and while the federal government has dedicated plenty of money to remediation projects, “very little of that money is making its way down to the people doing the work.”

“This work is expensive, and often done in ad hoc fashions outside normal research channels,” Segura added. “As a result, I think many of the studies and the results are lost to the researchers.”

The findings from the project Segura and Thomas did together on the spilled coolant, for example, were presented publicly but never published in an academic journal.

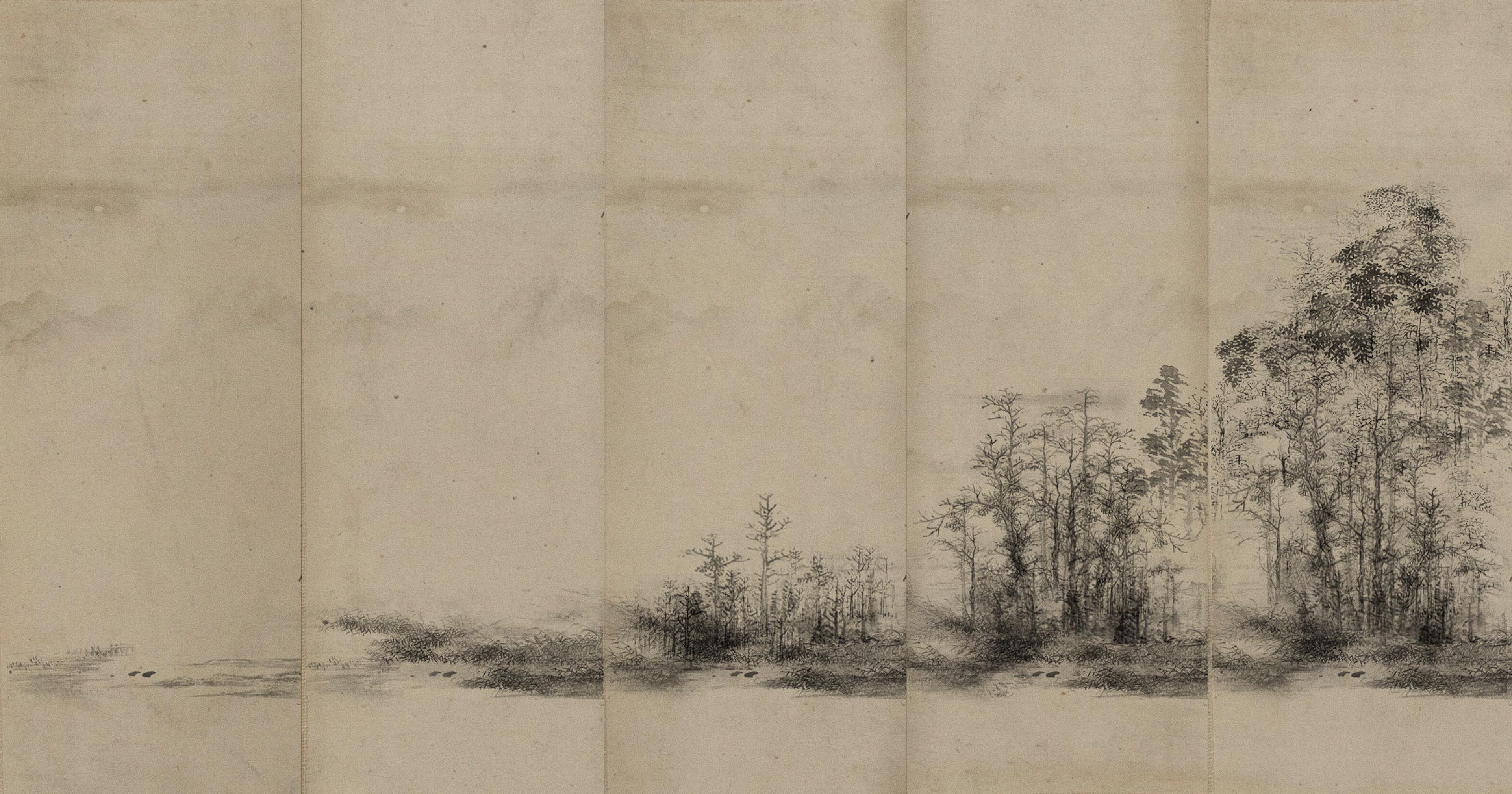

Some of the largest-scale studies Stevenson has seen are her own: As part of her PhD research, she identified native plants growing on polluted sites throughout Los Angeles, then planted those along with symbiotic fungi previously shown to remove cadmium and lead from the soil at three separate 3-acre brownfield sites. The one-year study on these polluted sites showed reduced heavy metals and petrochemicals in the soil, thanks to this combination of phyto- and mycoremediation. While the results are exciting, Stevenson emphasized that the study needs to be replicated and tested further, and scaled up.

The EPA initially posed a catch-22, basically telling Stevenson that she couldn’t test a new method in the field unless it had already been proven in the field.

“I’m really, really passionate about trying to do more of these,“ said Stevenson, ”trying to continue to scale and test these methods in field conditions.“

One of the impediments she repeatedly encounters is regulatory agencies, which initially stood in the way of her brownfields project. The EPA initially posed a catch-22, basically telling Stevenson that she couldn’t test a new method in the field unless it had already been proven in the field.

The lack of thoroughly proven methods also makes it challenging to encourage experimentation with mycoremediation on farms. Because farmers are often “maxed out,” Stevenson said, trying an experimental method isn’t a popular undertaking. The same logic often applies to city agencies that own sites like brownfields.

“The folks who own or run those lands just don’t want to try something that hasn’t been proven, even though it might actually address the issue and build healthier soil and have all these other benefits and be a lot cheaper than any other remediation methods,” she said.

Still, Stevenson remains hopeful, and the broader community of mycologists, mushroom farmers, and enthusiasts is pushing forward in North America and around the world. In Germany, mycologist Dietmar Schlosser has been studying how plants and fungi can degrade environmental pollutants for two decades, and has gradually seen more attention drawn to his field in recent years.

“Fungi are known to be excellent polymer degraders,” said Schlosser. “Polymers are thick and they have to be decomposed to smaller pieces, and fungi are specialists for doing that. Considering that with the increasing attention paid to biodegradation of plastics, they are gaining more interest now than 10 years before.”

As researchers like Stevenson and Schlosser work to demonstrate and document the potential of mycoremediation, there are still many blanks to fill in.

“Fungi are very powerful organisms, and I think we are just now beginning to become aware of their capabilities,” said Segura. “We do not understand how their nonselective digestive enzymes work. Imagine what we might be capable of doing after we understand those channels and replicate them on a large scale.”