Hemp’s detoxifying properties have been proven to tackle PFAS pollution. Through ongoing legal challenges, researchers are exploring its potential.

After the 2018 Farm Bill legalized hemp production for the first time since the 1970s, Chelli Stanley started seeking out polluted land for an experiment. Hemp is a hyperaccumulator, meaning toxins from soil can be absorbed through the plant’s roots. Inspired by Indigenous activist John Trudell, the journalist and environmentalist wanted to grow hemp to see if it could clean up contaminated soil.

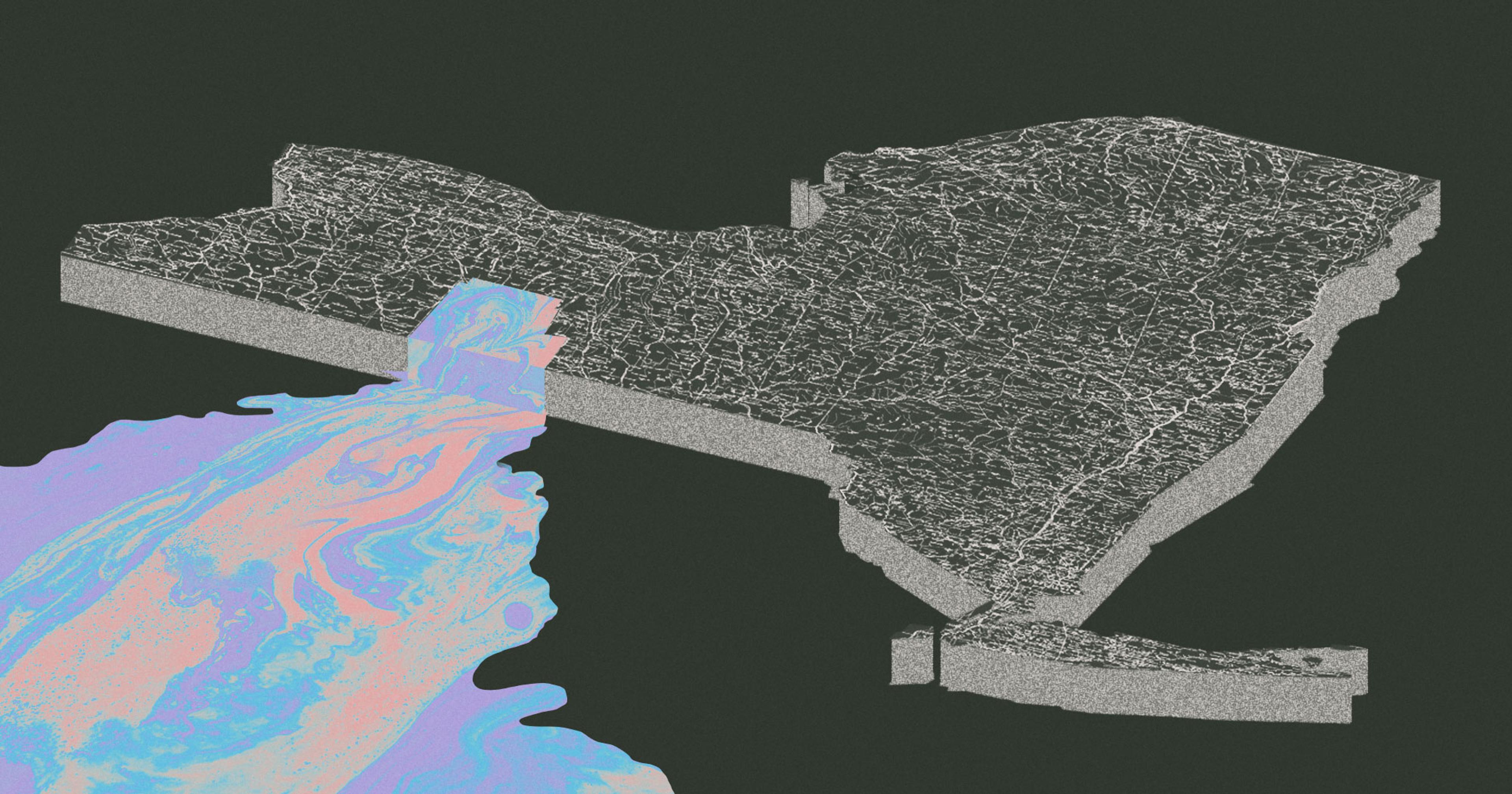

She eventually met Richard Silliboy, Vice Chief of the Mi’kmaq Nation. In 2009, the Tribe had acquired the former Loring Airforce Base. Located in the small town of Limestone, Maine, the military previously used the land for over 40 years as a firefighting testing area. Upon inspection, the Tribe found the soil and groundwater was thoroughly contaminated with PFAS from toxic firefighting foam. It was so polluted, in fact, that the EPA deemed it a Superfund site, putting it on the national priority list for hazard clean-up.

Eager to collaborate, Silliboy partnered with Stanley in 2019 and co-founded Upland Grassroots alongside community activists, Tribal members, and researchers at a variety of institutions. The goal: to try using fiber hemp to remove the PFAS.

While industrial hemp has been used for phytoremediation efforts before on heavy metal toxins and radioactive isotopes — one of its large successes was on agricultural lands in Chernobyl after the 1986 nuclear disaster — hemp’s potential with PFAS is a newer subject.

PFAS, or Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as “forever chemicals,” are a group of thousands of different compounds that don’t easily break down in the environment. Some compounds aren’t harmful, but many others have been linked to health issues including liver damage, thyroid problem, and cancer.

Upland’s creation coincided with the rise in PFAS found in farms all over Maine due to the usage of PFAS-heave sewage sludge as a low-cost fertilizer applied on fields. A practice used since the 1980s, most sewage sludge is said to contain PFAS due to wastewater treatment plants being unable to break it down. It has since contaminated waterways and crops; sickened farmers; killed livestock; and led to multiple people losing their farms.

Maine eventually banned sludge usage and is trying to repair the damages, but lawsuits are popping up against regulators such as the EPA; the agency still promotes its usage, while little federal regulation has taken place. Nationwide, according to the Environmental Working Group, nearly 20 million acres of farmland have been treated with sewage sludge.

Even if the EPA bans its usage, how to repair the land remains an open question. Can hemp be the answer, and what are the potential benefits and barriers?

Research Commences

Inspired by the Loring cleanup project, Lesley Putman, chemistry professor at Northern Michigan University, began doing research with her students. They started by exposing hydroponically grown hemp to PFBA, a nontoxic PFAS compound. The plants successfully took it up in the leaves, stems, and flowers.

Next, they exposed hemp to toxic PFAS compounds such as PFOS, which was found at Loring. Putman watered some hemp plants with a PFAS solution, while other plants got treated by the sewage sludge that she got from the former KI Sawyer Airforce base, another property which had PFAS contamination from firefighting foam.

She said the experiments with the toxic PFAS didn’t affect the growth of the plant. The team was disappointed that it only got sequestered in the roots, but Putman said it’s a good start.

“There is persistence in experimenting with it, but that’s what science is about. It’s about finding solutions.”

Furthering the research, one of her students recently started looking into how PFAS affects the cannabinoid content in cannabis plants. She also recently partnered with an area business that specializes in fungal remediation. They inoculated the roots on some of Putman’s hemp plants with fungi to see if it could help degrade the PFAS more quickly, but she hasn’t noticed a difference.

Most recently Putman presented her team’s work at a seminar, highlighting that their studies showed hemp seems to be most effective in sites where contamination is highest — a surprise.

“There is persistence in [experimenting with it], but that’s what science is about. It’s about finding solutions,” she said.

A Web of Regulations

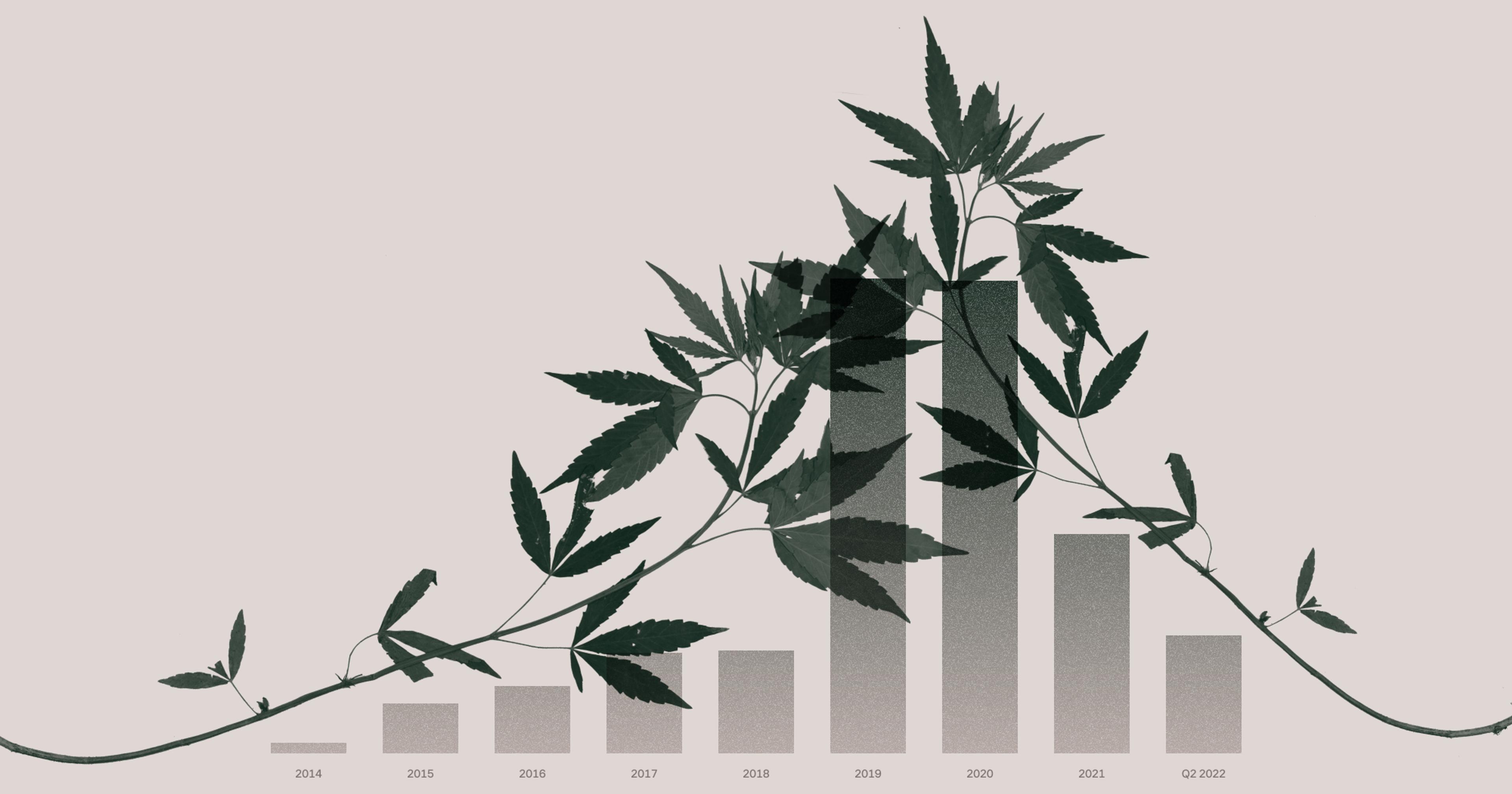

Though Putman has been doing phytoremediation for years, it wasn’t always easy to research hemp. The Agricultural Act of 2014 had made hemp legal for academic study, but it remained heavily regulated because it was still considered a controlled substance.

Even after it was removed from this list, Putman had to apply for a grower’s number, which involved a background check and GPS coordinates for where she planned to grow. The university designated a fenced-in outdoor area, where she used above-ground planters to avoid contaminating the soil. Hanging on the entrance into the area is a sign with her grower number, and underneath in blazing capital letters: “HEMP IS NOT MARIJUANA.”

“Not only is there still confusion about the difference between hemp and marijuana in government, there’s still very much confusion between industrial and cannabinoid hemp,” said Erica Stark, executive director of the National Hemp Association (NHA).

Industrial hemp is cultivated for fiber and oil, and used in products like textiles, paper, and construction materials; it has low levels of THC (typically less than 0.3%) and doesn’t get you high. Cannabinoid hemp is grown specifically for its high concentrations of cannabinoids like CBD and also contains low levels of THC that can produce a calming effect.

“We are still facing the problem of various government agencies not even understanding or acknowledging that hemp is legal.”

Stark said that when the 2018 Farm Bill passed, the word “industrial” was dropped from the definition intentionally to protect the cannabinoid industry, but as an unintended consequence that made it more difficult to have distinct rules for fiber and grain hemp.

“We are still facing the problem of various government agencies not even understanding or acknowledging that hemp is legal,” she added.

The NHA has been working on the Industrial Hemp Act of 2023, introduced to the Senate last March. The bill would create a legal distinction between industrial and cannabinoid hemp to be able to lessen some of the regulatory confusion.

Potential for Profit

In terms of growing hemp for phytoremediation, Stark says she doesn’t see too much yet in the ag sector, likely for several reasons. Partly, it’s because of regulatory hurdles. Compliance testing is expensive and hard to accommodate on several acres of land. NHA hopes the bill will also get rid of the arduous testing protocols if it’s being used for phytoremediation.

Stark also said that it needs to be known what products can be safely made from hemp grown on contaminated land to be able to create value-added products. This way, instead of paying to fix the contaminated land, farmers could not only be doing something good for the environment but also generate revenue and get some of that money back.

Stark said there still needs to be more research on what can be done for viable options, and it would likely not involve anything ingestible. Some are putting their hope in biofuels.

“The most important thing would be finding a way to get the PFAS out of the hemp.”

Bryan Berger, chemical engineer and professor at the department of chemical engineering at the University of Virginia, has been collaborating with the USDA to build pathways toward converting hemp into fuel. They recently released a study in April about the process of conversion.

The process breaks down the plant’s cellulose, which has sugar valuable for the fermentation process that can help fill in fuel products that he says will hopefully be an answer to getting away from petrochemicals. That said, it’s still an open question whether PFAS-contaminated hemp could ever be safe enough to use in this fashion.

“The most important thing would be finding a way to get the PFAS out of the hemp,” said Vice Chief Silliboy, adding that they currently can’t burn it, because the PFAS would just go back into the atmosphere.

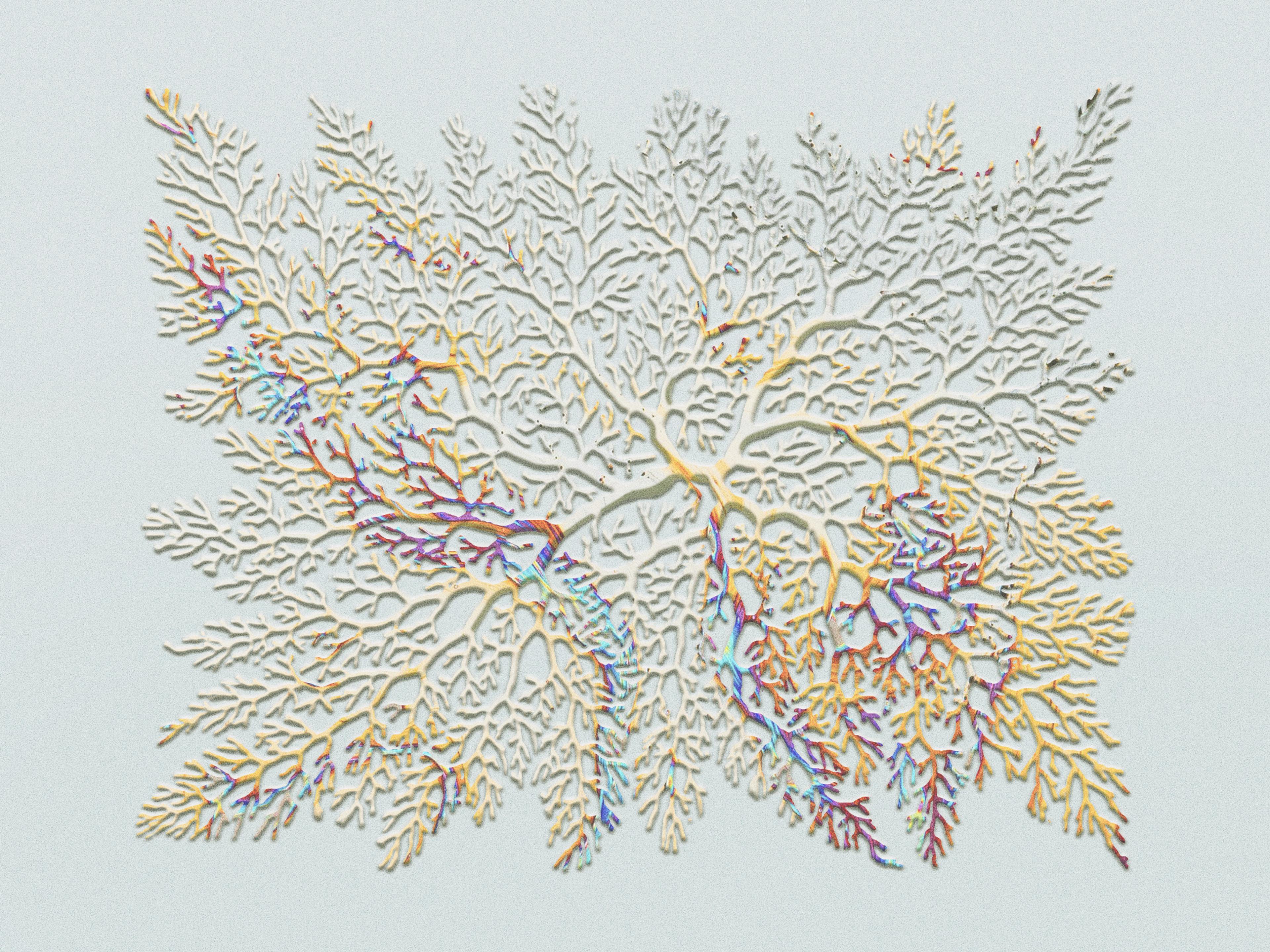

To degrade some of the PFAS in the harvested hemp, scientists on the Upland project have been using a process called hydrothermal liquefaction, a process of breaking down the biomass that was spoken about in their joint-published study on the trial. However, so far their studies have shown that a small amount of contaminants remain in the plant.

The Uplands project currently has a company remove and safely dispose of the contaminated plants. However, they said that one member of their team has been researching how to break down the PFAS using microbes.

Hemp’s Future Legacy

UVA’s Berger lives not too far away from Albemarle County in Charlottesville. which used to be one of the largest hemp processing facilities in the U.S., before it got criminalized in the 1900s due to what some believe were dirty tricks from the timber industry. Hemp was once used widely by the military; the government even encouraged U.S. farmers to grow it.

“A lot of history was lost,” Berger said, adding that if you talk to 3rd and 4th generation farmers there, they remember their grandparents growing hemp.

Berger, who is part of the team of researchers with Upland Grassroots, said that there still needs to be more studies done about converting contaminated hemp into biofuel. He hopes that maybe the Upland project can help move the dial with it continued research, which thanks to a grant will be continued over the next few years.

They grow from June through mid-August and harvest once the plant starts flowering, because there is a lot of PFAS uptake in the pollen, and they don’t want it blowing around. This summer the group tried to plant 50 to 60 different varieties of hemp to see which works best.

“We can do nothing with the property. We can’t put homes on it.”

While the conclusion the team made was that it doesn’t offer a comprehensive solution, hemp has effectively cleaned up some of the soil, and they will continue using it. The team also made another observation, that their research underscored the importance of involving community members in research aimed at remediating their lands.

Some of the group have also been trying to remediate nearby land that was contaminated with jet fuel, but they aren’t yet working with scientists on that.

Silliboy said that he hopes the group gets enough documentation that the Air Force will come back and do some of the cleaning or compensate the Tribe because there is still so much contamination. “We can do nothing with the property. We can’t put homes on it,” he said, adding that they were hoping to at some point put up a portable mill for economic development.

In the meantime, he said, “It’s very slow progress. As long as we’ve got people willing to work with us, I’m willing to keep tagging along and doing what we can.”