Could a warming climate prove a boon for California orchards?

Twenty years ago, Frog Hollow Farm grew heaps of Bing cherries.

Located an hour’s drive east of San Francisco, the farm grows mostly stone fruits, from apricots and plums to pluots and cherries — including the ever-popular Bing variety. In recent years, however, farmer and founder Al Courchesne and his team have been forced to move away from Bing cherries for one simple reason: It’s not cold enough.

“Old varieties we used to love in California, those require around 800 chill hours every year, but in Brentwood we’ve been getting less and less in the last 20 years,” said Rachel Sullivan, farm operations manager at Frog Hollow. “That’s happening statewide.”

With the changing climate bringing warming temperatures to California, several of the state’s growing regions have been experiencing a twofold impact. Fewer cold days in the fall are affecting many crops’ ability to properly flower come spring. And on the flip side, fewer cold days in the spring may translate to a decreased need for frost mitigation measures.

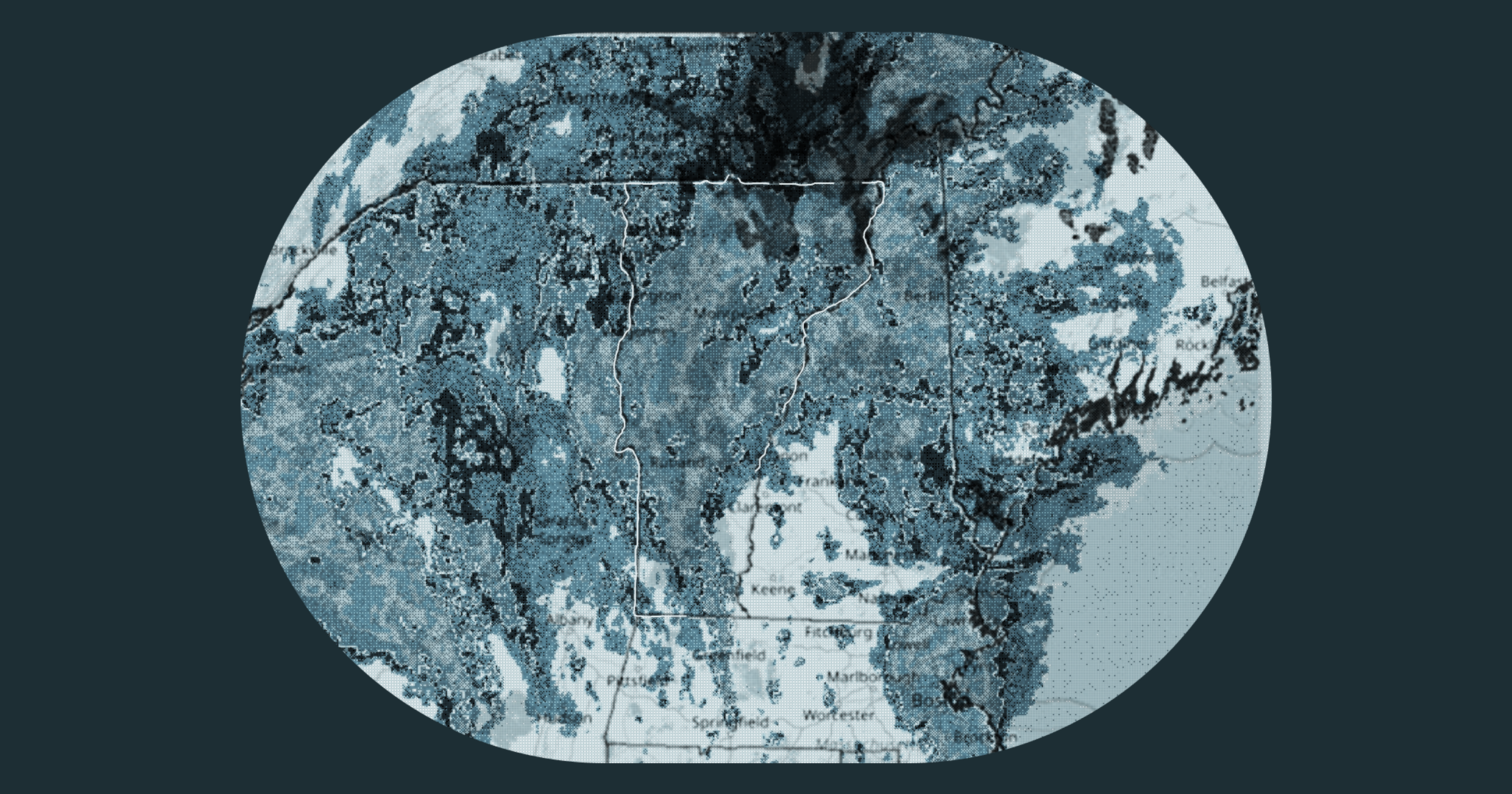

Findings from a 2020 study from researchers at USDA, the University of California, Davis, and the University of California, Merced, back Sullivan’s experience. The study focused on the reduction in frost hours (time between roughly 28 and 35 degrees Fahrenheit), as well as the reduction in chill hours (time between roughly 32 and 45 degrees Fahrenheit).

The California researchers found that the state is set to experience fewer and fewer spring freezes. Using climate data and predictive models, researchers forecasted that by the middle of the 21st century, the state will experience on average 63 percent fewer frost hours. The paper highlighted three high-value perennial crops and found that the majority of almond and orange crops could experience 50 to 75 percent less frost exposure, while avocado acreage may see more than 75 percent fewer frost hours.

Lauren Parker, lead author on the study, as well as a project scientist at UC Davis affiliated with the USDA California Climate Hub. called the projections a double-edged sword. She noted that warmer winters and springs will reduce the risk of frost but increase the risk of other problems like insufficient chill accumulation and pest pressure.

“Within the climate change context, there will be winners and there will be losers and there will be everything in between,” she said. “And most of us will be a little of both.”

Like almonds and many other fruit and nut trees, cherries require a certain period of cold weather in the fall in order to properly develop and resume normal growth, flowering, and fruiting in the spring. While this chill requirement varies depending on species, age, and other factors, many varieties such as Bing need hundreds of cumulative cold hours in order to bear the most fruit.

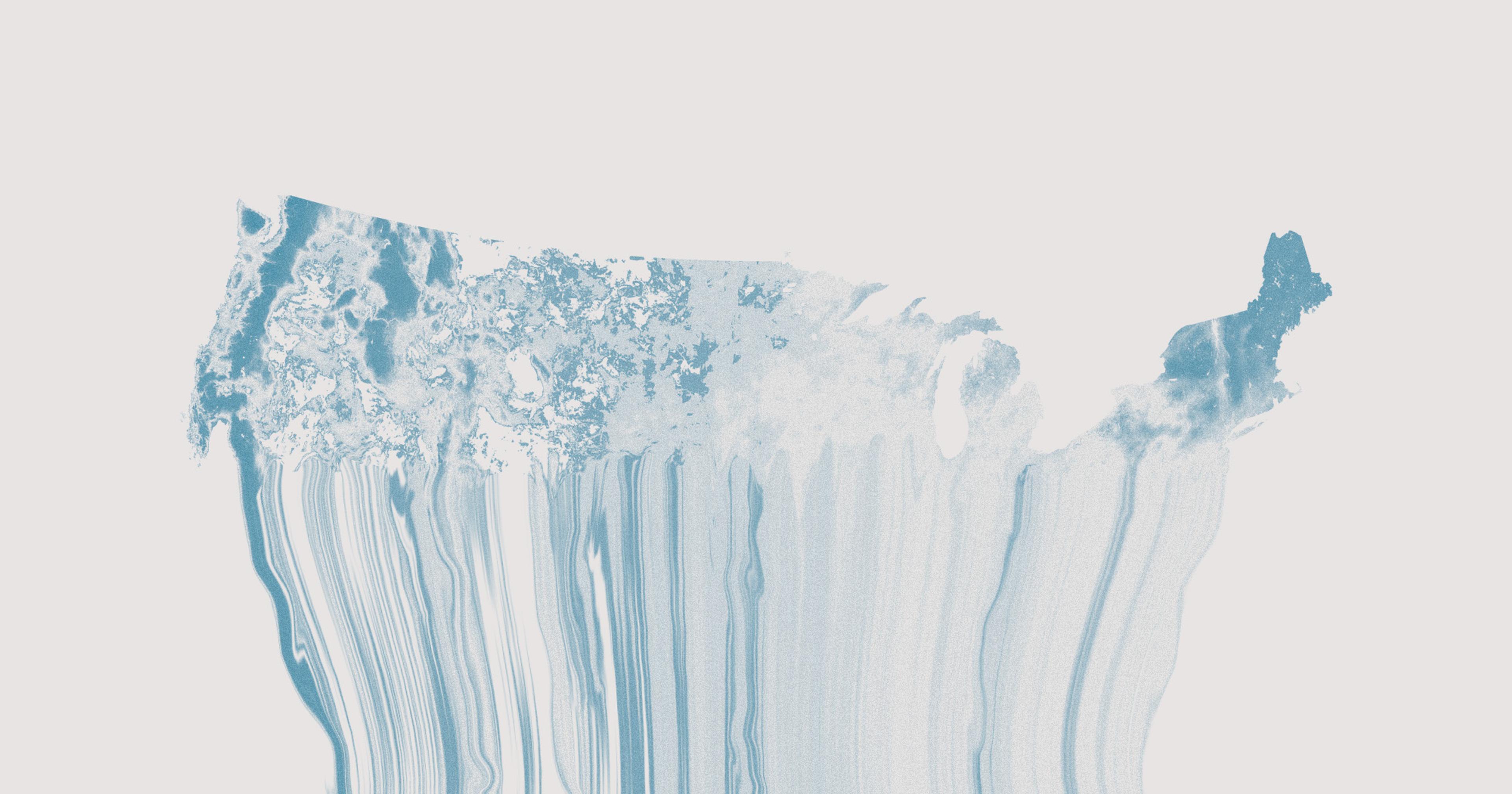

Moreover, while crops are budding in the spring, they are particularly sensitive to temperatures below freezing. And surprise frosts can be costly — an ill-timed freeze in California’s Central Valley in 2018 resulted in more than $40 million in crop damages. Elsewhere, a record-breaking late spring freeze in Vermont earlier this year damaged thousands of acres of crops, including 50 percent of primary bud loss in many vineyards across the state.

“Within the climate change context, there will be winners and there will be losers and there will be everything in between.”

One common strategy used to protect crops from frost is to irrigate them with water, a process that generates a small amount of heat. The study noted that fewer frost hours could lead to water savings for farmers, as well as reduce the amount of CO₂ released via irrigation pumps. However, the authors were quick to note that any potential savings in these departments would likely be offset by an increase in water and energy demands due to rising temperatures. The greenhouse gas savings would also represent a drop in the bucket compared to the roughly 9 million metric tons of CO₂ emitted per year by the state’s crop-growing industry as a whole.

A spokesperson for the Almond Board of California also cautioned that the variability in both California’s many microclimates would make it difficult for growers to capitalize on any potential benefits from a warming climate.

“The adverse consequences of climate change, including increased disease susceptibility, challenges in synchronizing blooming between different almond varieties and pollinizer trees, and issues related to water availability, are likely to far outweigh any benefits gained from frost avoidance,” the spokesperson wrote in an email.

Fewer cold days will also likely lead to an increase in insects like the navel orangeworm, an invasive pest that, according to longtime grower and nursery consultant Ed Laivo, has “never been a worse problem.”

“I don’t think the warming of the climate is beneficial at all,” Laivo said. “If anything, it just creates a broader environment for these organisms to multiply and sustain themselves.”

“There’s not one magic bullet that’s going to save ag. It’s going to take a lot of effort in different respects.”

Flooding, drought, smoke, fluctuating temperatures — the unpredictability brought on by climate change has made it increasingly difficult for farmers across the country to maintain healthy crops and produce consistent yields year after year.

“[Growers] really want to be able to say ‘I’m going to plant this variety and it’s going to be there the entire time I’m doing this,’” Laivo said. “That’s what they hope for, and it’s never the case.”

At Frog Hollow, farmers have planted newer cherry varieties developed by nurseries to require fewer chill hours. But this strategy represents an expensive, time-consuming investment that isn’t guaranteed to pay off, Sullivan said.

“When you plant a new orchard, you have to wait three years before you can get a significant crop from those trees. If you pull out an old Bing tree that you might get a crop on once every five years, is that going to be more expensive than ripping out the whole orchard?”

“It’s a lot of time and money. But it is a solution.”

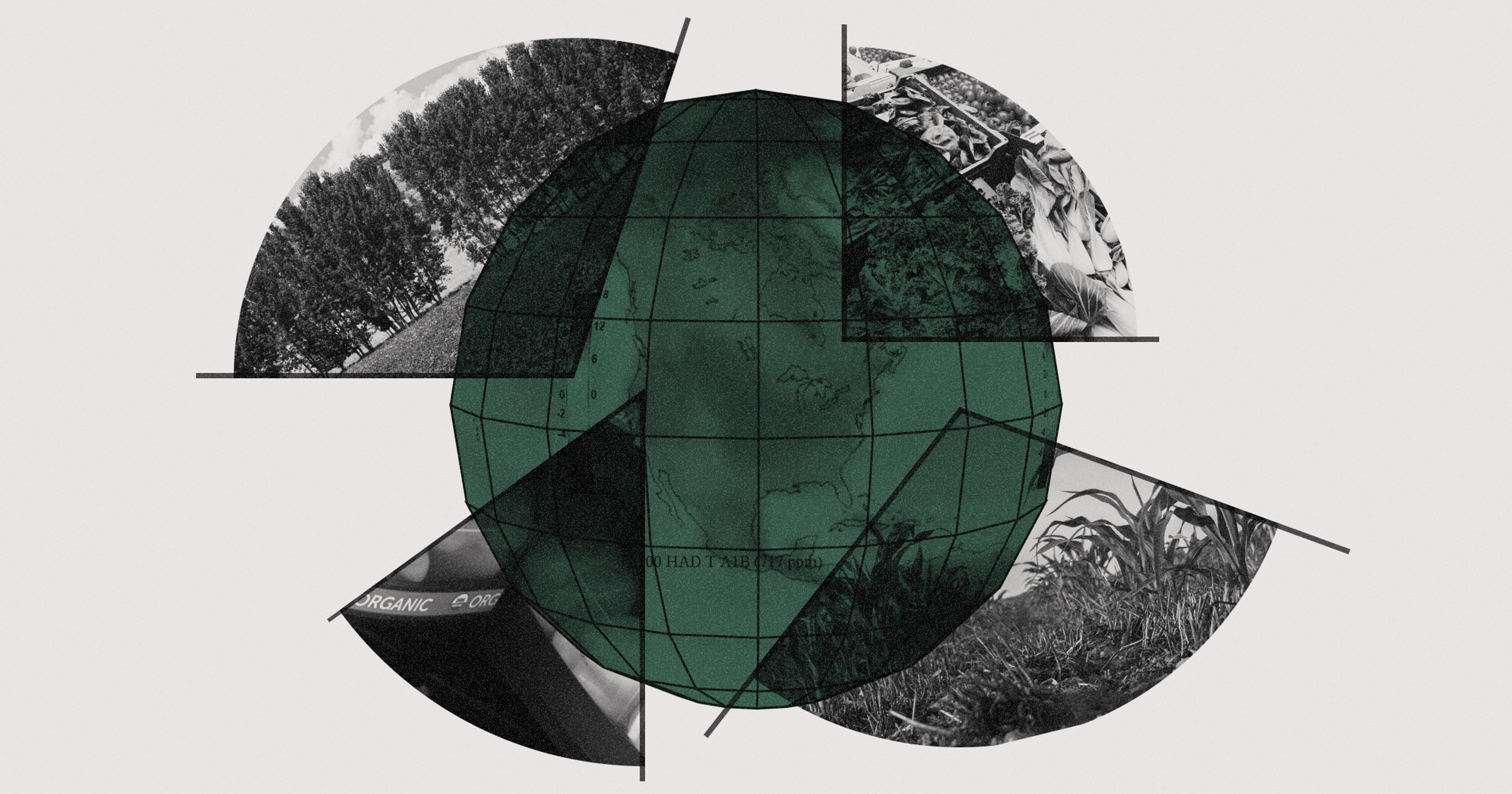

Other potential solutions include building more accurate models to help farmers plan for or react to weather events, said Jodi Johnson-Maynard, head of the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences at the University of Georgia. This includes a set of online risk management tools for farmers based on crop and location-specific data, built by the frost study researchers.

And, Johnson-Maynard added, all these efforts — toolkits, new crop development, scientific study, and policy implementation — need to be engaged collaboratively in order to give farmers the greatest chance of success.

“You have to think about the market at the same point in time you’re thinking about the agronomy and the biology and how to grow that crop,” she said. “Because if there’s no market for it, it’s not going to help the farmer. Those things have to be developed side by side.”

“There’s not one magic bullet that’s going to save ag,” Johnson-Maynard added. “It’s going to take a lot of effort in different respects.”