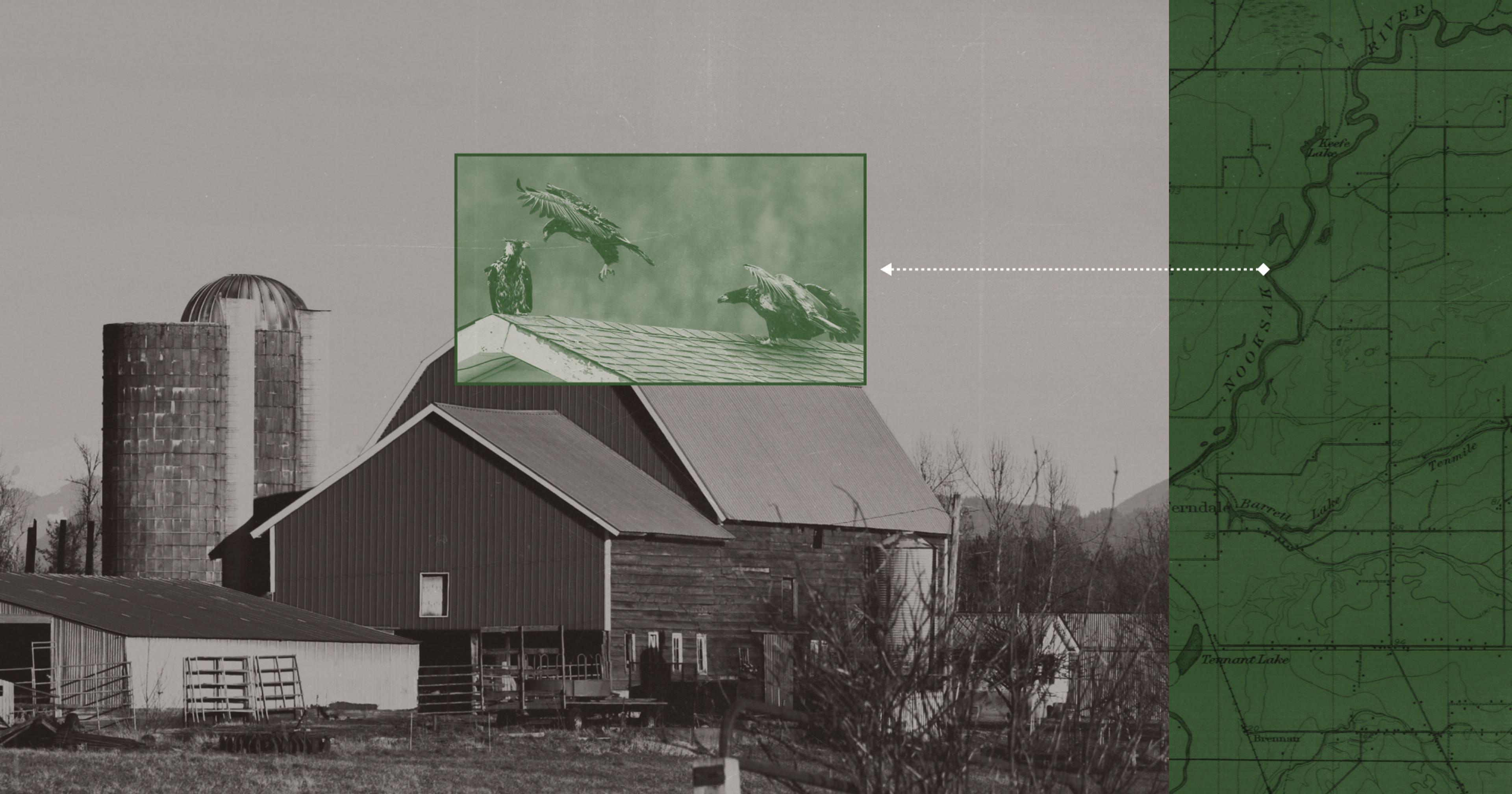

There’s a new movement afoot, encouraging farmers to create bird habitats on their land. It provides natural insect control while mitigating the massive bird losses of recent decades.

The complicated relationship between food producers and wild animals is an age-old saga — cattle ranchers and wolves, home gardeners and rabbits, ranchers and beavers. Birds are no exception; the wrong species can decimate a farmer’s entire crop, but if managed effectively, birds can also offer crucial pest control.

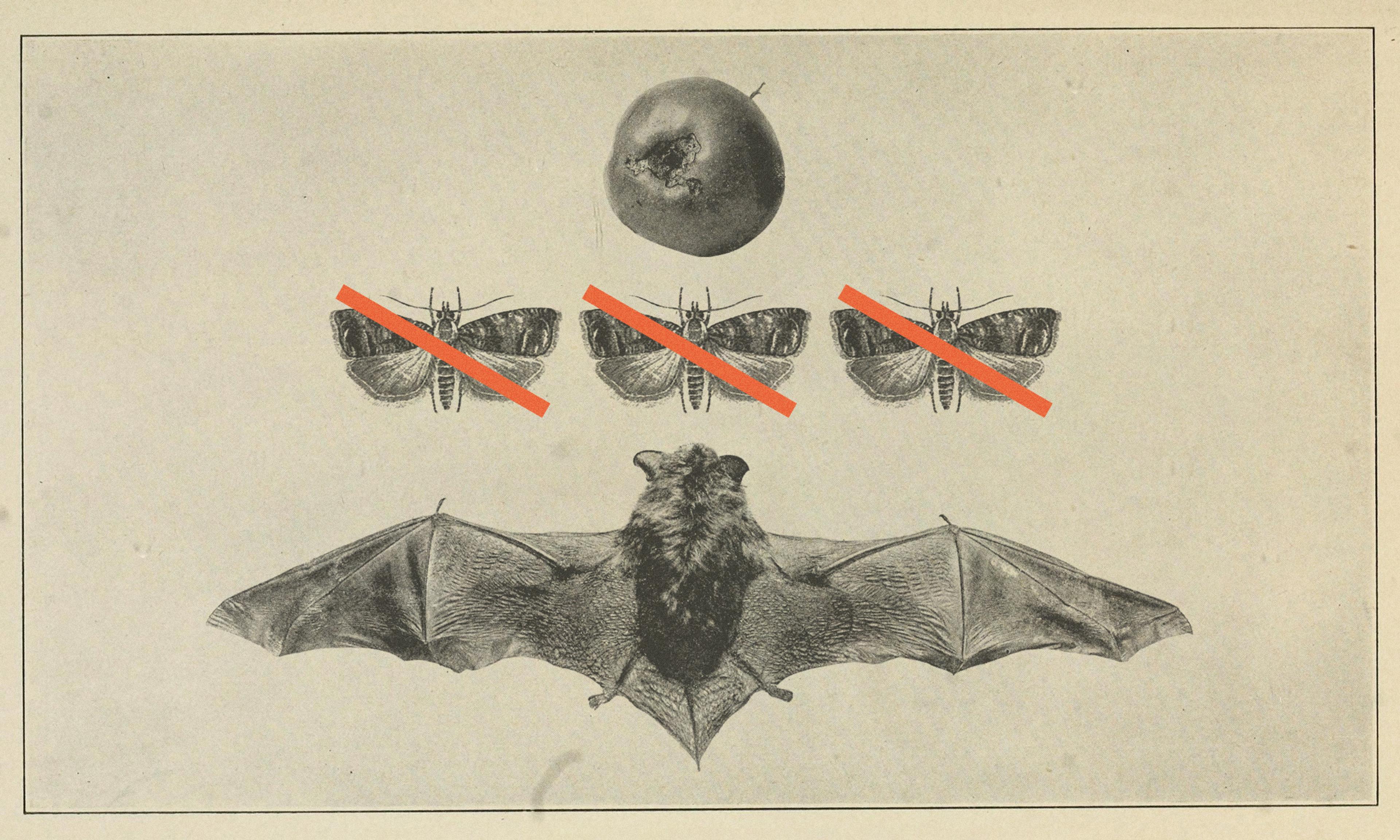

The cost-benefit analysis might seem simple on its face: If birds have the potential to be problematic, keep them away from your crop and utilize pest control methods that seem more reliable. But, of course, it’s not that simple.

A 2019 report by the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology found that North America has lost nearly 3 billion birds since 1970 — as in, nearly 30 percent of the total population of breeding adult birds has vanished in the last 50 years. More than 90 percent of those losses are seen in just a few common species such as warblers, finches, sparrows, and blackbirds. The researchers peg this dramatic decline as an environmental crisis; birds are a crucial part of our ecosystem, serving major roles in pollination and seed dispersal.

Farming — specifically the large-scale, mechanized monoculture that’s become more prevalent in the last half-century — is a major contributor to this crisis. A 2005 article in Science identified agriculture as “the greatest extinction threat to birds,” primarily because of the loss of natural habitats, interactions with farming equipment, and death from pesticides.

“Agriculture’s footprint is taking out habitat and water resources,” said Jo Ann Baumgartner, executive director of the Wild Farm Alliance (WFA). “Then there’s the pesticides that harm birds, and those pesticides also harm the food source: the insects that birds eat and the plants that support birds.”

The WFA is a non-profit organization dedicated to increasing biodiversity by expanding the idea of wild farming, a practice that both supports and benefits from untamed nature. The WFA promotes the presence of flowers, native trees, shrubs, and wildlife on farms. It also encourages farmers to keep as much soil as possible covered in plants (crops or cover crops) to control erosion, provide habitat for wildlife, and promote the build-up of carbon in the soil.

The WFA advances these principles through three primary programs: the Farmland Waterways Trail, the Farmland Wildways Trail, and the Farmland Flyways Trail. Each of the trails is intended to create a connected network of wild space across North American farms. The WFA also encourages organic farming practices, endeavoring to create a more holistic, closed-loop system in which nature and farmers are working in collaboration rather than opposition.

The Farmland Flyways Trail is WFA’s effort to address the crisis of bird decline. It encourages farmers to invite birds onto their farms with nest boxes, perches, and native plantings, and also gives lessons on how to manage the birds to mitigate crop damage. Participation in the trail is free and self-monitored, and farmers can register with a simple online survey.

“We watched these birds … swoop down and get the army worms. We have really seen a decrease in our pest population.”

The WFA tracks participating farms on the Farmland Flyways Trail map, which currently includes 200 farms with about 2,000 bird boxes across the country. Most of the farms are concentrated on the West Coast, where the WFA is headquartered (a new satellite office was recently established in Minnesota).

A number of studies and reports indicate bringing wild birds onto the farm is often a net positive for farmers. Much of this evidence can be found in the publication Supporting Beneficial Birds and Managing Pest Birds, a resource authored by the WFA in collaboration with Sacha Heath, now a senior scientist at the San Francisco Estuary Institute, and Sara Kross, a senior lecturer at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand.

“The literature is showing benefits after benefits after benefits from doing things like planting native hedgerows for farmers,” said Kross. “They are often bringing in insectivorous birds and birds that provide benefits to the farm and not necessarily increasing the number of pest birds and the amount of damage from pest birds. So that bird equation seems to be tipping more on the beneficial side than the cost side.”

Pest birds are birds like crows and starlings that tend to flock, creating large groups that can do quick damage to a farmer’s crop. Hedgerows, one of the strategies promoted by the WFA, are actually found to discourage flocking birds, which prefer to forage in large, open areas.

Some species of songbirds may switch to a plant-based diet during certain parts of the year, thus becoming a pest by feeding on a farm’s crops, rather than the insects. There are usually specific times in the growing cycle when this becomes problematic, and the WFA offers a variety of strategies for addressing this, including visual and audio scare tactics and crop exclusion (netting). Farmers can also discourage pest bird behavior by allowing the first few rows of a crop to go to seed, providing a non-crop food source for the birds, and also by inviting predatory birds like raptors and kestrels to the farm with additional perches and nest boxes.

Supporting Beneficial Birds and Managing Pest Birds looks at the role of various species of birds in several different types of farms, including nut crops, fruit fields and orchards, mixed crops, grasslands, and pastures. An appendix of 118 avian pest control studies found that, in most cases, birds provided valuable pest control and inflicted negligible damage to the farmer’s crop.

“I have not seen a single drawback.”

“We are really trying to help growers understand why habitat can be beneficial in all these different ways,” said Baumgartner.

The organization’s goal is to reach 500 farms and 5,000 bird boxes within the next two or three years, by inspiring more farmers to install boxes and also capturing data about farms that have existing boxes.

Mountain Sun Farm, an organic vegetable farm in Mentone, Alabama, is the only farm in the Southeast that’s listed on the map. Owners Liz Simpson and her husband Brian installed five bird boxes on their property at the end of 2021, and since then, they’ve also increased native pollinator plantings like buckwheat, sweet alyssum, and sunflowers to provide additional food sources. The Simpsons report dramatic improvements in pest control. Before installing their bird boxes, the farmers were in a constant battle against destructive cucumber beetles.

“We would see them starting in February or March,” said Liz Simpson, “and they would go all year. It seemed like year-round we would have these cucumber beetles. I don’t know what type of bird would eat those, but we seem to have them because” they’re seeing a lot less beetles.

Army worms were another pest that attacked a cover crop field of sun hemp at Mountain Sun Farm.

“While Brian was mowing it, we watched these birds … swoop down and get the army worms,” said Simpson. “We have really seen a decrease in our pest population.”

Simpson thinks that their diverse crop array is advantageous in terms of the benefit they see from the birds.

“This is not some new, hippie thing to be doing. This was mainstream farming only three or four generations ago.”

“Growing a diverse range of crops helps us with that: If we lose something because of a pest bird, it’s okay,” she said. “But if you’re growing one crop and [a specific bird species is] a pest of that crop, I can see how it would be pretty scary to build houses and invite [other birds] along.”

Kross highlights that the correct type of box is important: The entrance hole needs to be the right size because if it’s too large, it can be accessed by starlings, which can often become a pest bird.

“But if [the entrance holes] are small,” said Kross, “they’re going to support tree swallows and bluebirds and wrens and other cavity nesting birds, most of which are insectivorous. So they’re usually providing benefits to farmers by then going out and eating whatever’s most abundant, which is often the thing farmers don’t want a lot of in their fields.”

In 2022, WFA monitored 174 boxes across the central coast of California and found nearly three quarters of them occupied, mostly by Western bluebirds. Honig Vineyard and Winery in Rutherford, California, started putting up nesting boxes in their vineyard 15 or 20 years ago, primarily to invite bluebirds onto the vineyard for pest control.

“Putting bluebird boxes in vineyards has been going on for quite some time,” said Kristin Belair, director of winegrowing and sustainability at Honig.

In addition to bluebirds, the vineyard also encourages the presence of predatory birds like barn owls and kestrels, which have helped control the rodent population. Belair estimates there are around a hundred nesting boxes on their property.

“I have not seen a single drawback,” Belair said. “We’ve done a lot to enhance biodiversity around the vineyard and we feel that we’ve gotten a lot of benefits from doing that.”

“Being organic is not a prerequisite, but we do caution growers about using pesticides.”

The concept of inviting birds onto your farm is not new. In 1885, the USDA established the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy, the first federal agency that was responsible for birds. The division was a precursor to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and its primary role was to study the positive effects of birds on agricultural pests. Kross explained that it wasn’t until after the World Wars, when chemical pesticides became more widespread and available to farmers, that using birds for pest management fell out of practice.

“Only a couple of generations ago,” said Kross, “farmers were learning about and really encouraging birds to come onto their farms to be the natural enemies of pest insects. This is not some new, hippie thing to be doing. This was mainstream farming only three or four generations ago. So it’s a little bit unfortunate that we have lost that understanding of the value that biodiversity can bring onto our farms.”

In addition to the general biodiversity benefits and sustainability aspect, bird boxes also have the tertiary benefit of reducing the need for on-farm pesticides.

“Being organic is not a prerequisite, but we do caution growers about using pesticides,” said Ashley Chesser, communications director for the WFA. “The goal is to create a holistic ecosystem where the beneficial birds and insects keep the pest insects in check. Spraying will kill off the insects the birds need to survive and can have negative impacts on the birds directly as well.”

Simpson remembers the temptation to use the strongest sprays permitted for organic farmers in the early days of their farming career.

“It’s hard to make a living farming,” she said. “The first few years, we were just in survival mode and we were just trying to make enough money to survive and the cost was so high. It was like, if this crop does not work and we can’t sell it, how are we going to farm next year? And so you get desperate.”

The WFA isn’t ignorant of the narrow margins that farmers face. Baumgartner herself was an organic farmer in the 80s and 90s.

“I really understand how hard farming can be and how farmers are on the edge of making a living or not,” she said. “Nature’s messy. It’s not like in every situation birds are great. But we can tip the scales towards having birds be beneficial on the farm. We can change things around.”

Of course, the benefits of wild farming and using farms to support the bird population cannot be assessed just by profit margins. There is an intrinsic value to supporting the natural world — humans feel more at home and relaxed in a space that is rich with plant and animal life than one that is bare and monotonous. Furthermore, increasing natural habitat on farmland provides greater carbon sequestration, which is crucial to healing a warming planet.

“Everything is connected,” said Baumgartner. “We can’t exist with just things that only benefit people. When we have those connections in place, our world is going to function better, be cooler, support more carbon storage, and hopefully bring back the biodiversity that is so fundamental to our psyche and how the world works.”

For North American farmers, birds are an integrated pest management system that worked well before, and could once again.