Funding for the water quality sensor system that monitors ag-related pollution has been axed, making it harder to hold the industry accountable, and nearly impossible for citizens to check the quality of their drinking water.

Editor’s Note: After this story was published, news broke that Iowa State University would use its own funds to keep the water sensors operative.

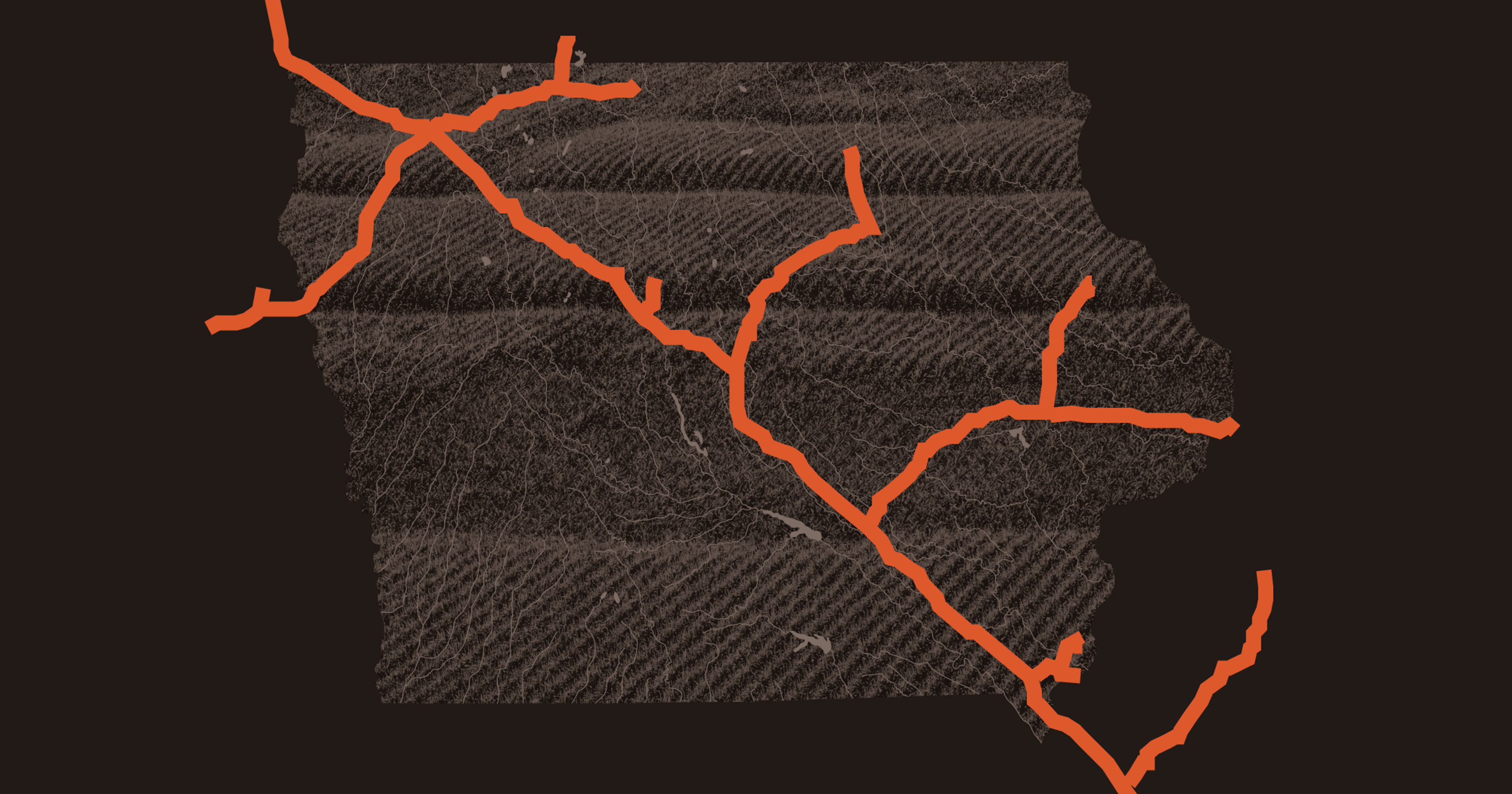

Agriculture is huge in Iowa, where farmland covers nearly 90% of the state’s acreage. Iowa is the country’s largest producer of biofuel and the top corn-growing state. But look beyond those infinite rows of corn and you’ll find a state drowning in water pollution issues.

With such an intense agriculture system comes ecological consequences. For decades, the quality of Iowa’s drinking water has been diminished by extensive use of fertilizers, conventional tillage, monocropping, and more. The state leads the nation in cropland soil erosion rates, which has only exacerbated its nutrient runoff problem.

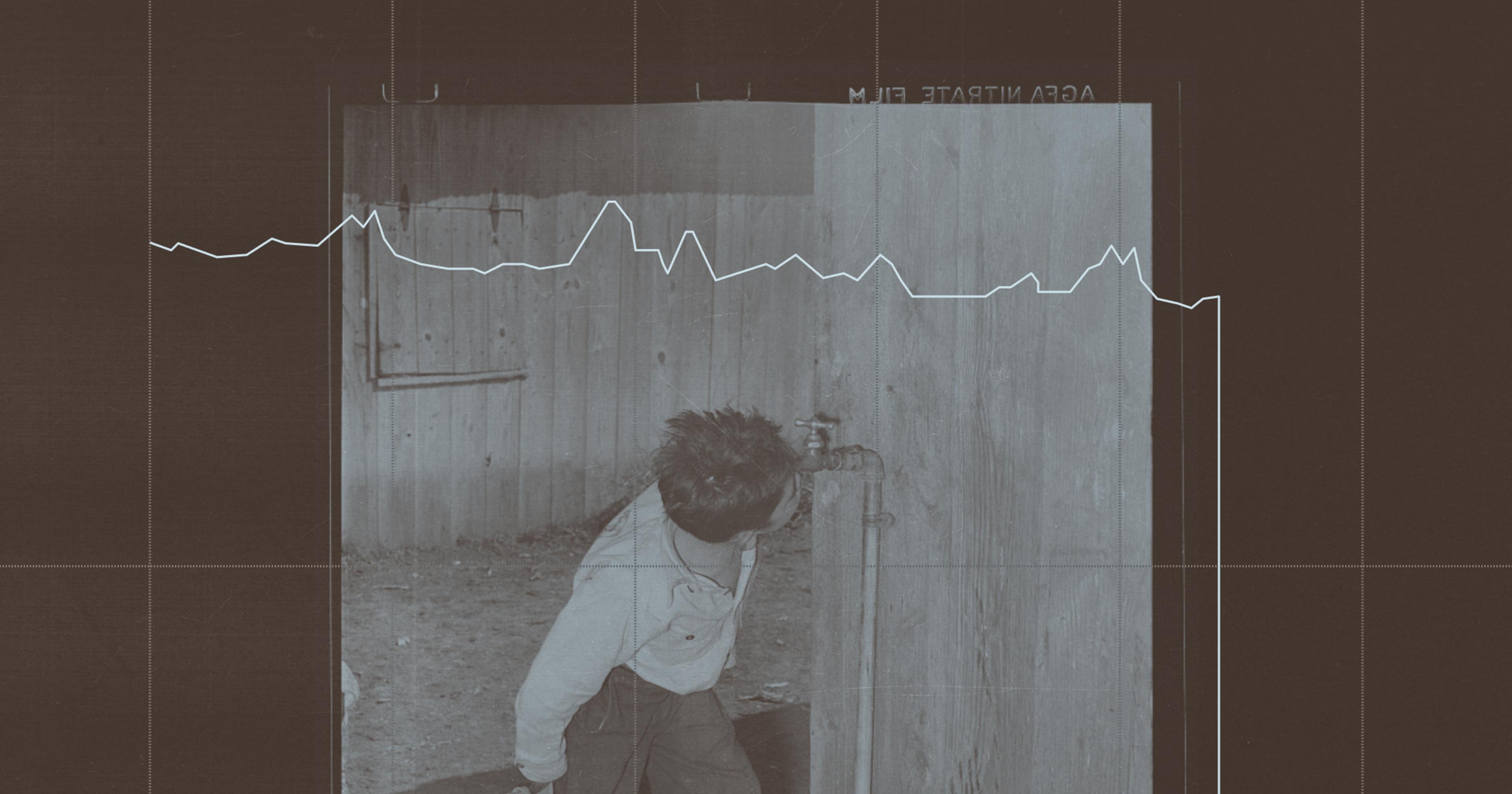

To keep track of these consequences, a network of sensors in Iowa rivers and streams have been collecting data on the quality of the water flowing through them for the last decade — but they might soon be pulled out. The sensors measure things like temperature, pH, and turbidity (how clear or cloudy the water is). More importantly, they monitor levels of nitrates and phosphorus, both common ingredients in commercial fertilizers that have a tendency to leach well beyond the fields they’re applied to, contaminating water supplies near and far.

This month, as many as 22 of the 60 sensors have measured nitrate levels above 10 mg/L, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency maximum contaminant level for nitrates at the same time. Any level above that can cause a slew of negative health effects, including nausea, dizziness, and headaches, as well as more extreme conditions such as cancer and “blue baby syndrome,” a potentially fatal condition that starves infants of oxygen.

Anybody can access the interactive sensor maps to get real-time updates on water quality — local government and researchers, yes, but also residents concerned about the safety of their drinking water. However, funding for the water quality sensors might soon be drying up, a move that could prevent scientists and citizens alike from accessing the important environmental data.

Earlier this month, Republican lawmakers approved a budget bill (SF 588) for agriculture, natural resources, and environmental protection that would cut $500,000 from the Iowa Nutrient Research Center (the organization that oversees the sensors) in FY 2024, the same amount it takes to run the project for a year. The cuts were specifically targeted toward the water sensors.

If the center doesn’t find another way to fund them, they’ll be pulled out of the water by July.

“To lose these sensors is losing a really important tool to try to understand that we’re not making the progress and that we do need to change course,” said David Cwiertny, professor of civil and environmental engineering and director of the Center for Health Effects of Environmental Contamination at the University of Iowa. “Without it, I think the intent is to make sure that we don’t change course.”

“We know that Iowa has an intense production system, 70% of our land planted to corn and soybeans ... This is very intense agriculture, like nowhere else on earth.”

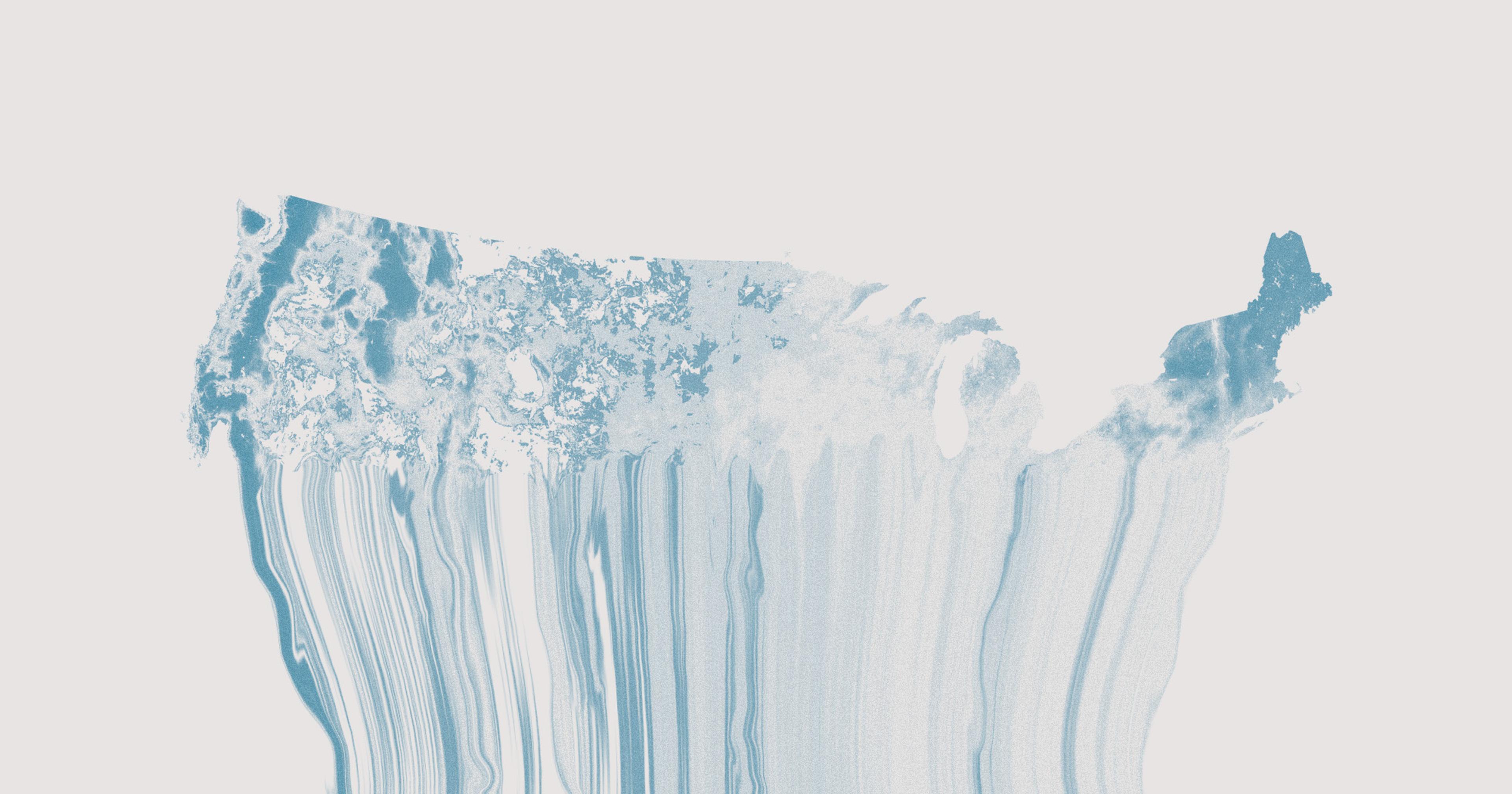

Ten years ago this month, Iowa passed a plan known as the Nutrient Reduction Strategy, which aimed to reduce its annual contribution of contaminants transported to the Gulf of Mexico — nitrogen by 45% and phosphorus by 29% — by the year 2035.

“We all know that Iowa has an intense production system, with 70% of our land [planted to] corn and soybeans. One out of every three hogs in the United States lives in Iowa. We’re the largest egg state, with 80 million laying chickens. We have about four million beef cattle, five million turkeys, and 220,000 dairy cattle. This is very intense agriculture, like nowhere else on earth,” said Chris Jones, who recently retired from his post as a research engineer in the University of Iowa’s Institute of Hydraulic Research. His new book, The Swine Republic: Struggles With the Truth About Agriculture and Water Quality, was released this month. “As a consequence of that, we have some environmental impacts that we don’t like very much, and that includes our impaired waters.”

It might only occupy 4.5% of the land area in the Mississippi River Basin, but the state contributes 29% of the nitrogen and 15% of the phosphorus found in the Gulf of Mexico. “We’re a big contributor to the Gulf of Mexico dead zone,” said Jones. “We are contributing to water quality degradation at the continental scale.”

When excessive nitrate is coupled with high levels of phosphorus in water, the contaminants can lead to harmful algae blooms that deplete waterways of oxygen, producing toxins that are harmful to both humans and aquatic animals. And all that agricultural runoff happening in Iowa has a literal trickle-down effect on other states and growing regions down the river.

“In-stream sensors are being defunded at the same time that ag groups are ‘celebrating’ 10 years of so-called progress on the Nutrient Reduction Strategy.”

The Nutrient Reduction Strategy was implemented to change that. But 10 years in, what sort of difference is it making, if at all? According to the 2018-19 annual progress report, the last one released by the Iowa Nutrient Research Center, the nitrates leaving the state had actually increased significantly. In 2000, 101,298 tons of nitrates flowed out of Iowa. In 2018, that number had spiked to 426,416 tons.

There are now online dashboards available to track the progress, but the information the reports contain is dense and difficult to interpret — and nowhere can you find real-time readings like the water sensor system offers.

It would seem that the water quality sensor network would be an important tool to have for tracking the state’s progress to its lofty goal of nutrient reduction. So why is it being defunded? According to the bill, Republican senators instead want to divert the money to the Iowa Department of Agriculture to fund nutrient reduction projects like bioreactors and saturated buffers, which reduce nitrate levels in water that passes through them. In other words, the money would go towards managing the problem’s consequences instead of solving its root cause: excessive application of commercial fertilizers.

“It’s not lost on anyone working in the water quality space, or the Iowans who pay attention to this work, that the in-stream sensors are being defunded at the same time that ag groups are ‘celebrating’ 10 years of so-called progress on the Nutrient Reduction Strategy,” said Iowa Environmental Council water program director Alicia Vasto in a statement. “Defunding progress reporting and monitoring is not the direction we should be going in our approach to nutrient pollution in Iowa.”

Jones has been especially outspoken about Iowa’s water contamination problem, and until last week, managed the network of water quality sensors across the state. For nearly seven years, he also authored a blog that drew attention to the state’s poor water quality and the political and industrial players involved in its demise — a blog that, according to Jones, upset two state senators.

“Keeping the public in the dark should make anybody feel uncomfortable. We should know what’s in our waterways.”

The researcher alleges that Republican Senators Tom Shipley and Dan Zumbach pressured University of Iowa officials to stop him from posting on the university-hosted website, threatening to pull the plug on state funding that supported the water monitoring project. Jones offered his resignation shortly after.

Zumbach — whose son-in-law runs a 11,600-head cattle feeding operation on Bloody Run Creek, where one of the sensors is located — denied the allegation, and told the Iowa Capital Dispatch that it was “reckless and possibly defamatory.” Neither Zumbach nor Shipley responded to a request for comment.

If the sensors are removed, Jones said large agribusiness concerns will gain more control over the narrative about the quality of Iowa’s water. “The industry and state government is wanting to message progress towards nutrient strategy goals in a positive way. The sensor network generated data that contradicted that,” he said. It seems “the objective here is to get control over the messaging so the industry can deliver messages to the public that paint this all in a positive way. And that’s certainly a lot easier to do without the sensors and without me.”

Without real-time data tracking the levels of pollutants in water sources, it becomes more difficult to track the source of a contamination — and harder to hold that source accountable. “What the sensors were doing was essentially facilitating the monitoring of improper behavior,” said Silvia Secchi, professor in the Department of Geographical and Sustainability Sciences at the University of Iowa. “If manure is improperly applied, you don’t have to wait three days for the fish to die because the sensor immediately tells you and you could send the [Department of Natural Resources] people there [to investigate].”

“By taking away the sensors that give us a chance to show if we’re making any progress [in nutrient reduction], then we’re basically flying blind. You can’t manage what you don’t measure,” said Cwiertny, who emphasized that the consequences of defunding the water sensor network extend far beyond one man’s career.

“Keeping the public in the dark should make anybody feel uncomfortable … We should know what’s in our waterways. To have that data taken from a very public display to no longer being accessible is problematic. We can’t have data like that be taken away, be hidden, because we have a right to know,” he said. “We should be making environmental quality data more available to citizens, not less.”