In The Mighty Red, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Louise Erdrich turns her attention to sugar beet production in North Dakota. It’s a farming novel for our times.

Few recent novels give agriculture its due. In contrast, farming is at the core of 19th- and even 20th-century American fiction, with its heroes formed through westward expansion.

“I don’t see enough fiction about contemporary farming, so I wanted to try,” Louise Erdrich told me on a phone call.

Erdrich, who is of Ojibwe descent and a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, reimagines the contemporary farming plot for our era of climate change in her latest book, The Mighty Red. Across her expansive body of work, which now totals 32 books, she has ignored the narrative assumptions U.S. audiences place on Native people, and written with precision and sensitivity. She has won the Pulitzer Prize, National Book Award, and National Book Critics Circle Award, among others.

The Mighty Red takes place in a sugar beet farming town in North Dakota’s Red River Valley of the North during the 2008 financial crisis. Kismet Poe, the protagonist, is a young woman with Ojibwe ancestry about to graduate from high school. Following a confusing tragedy, Kismet finds herself stuck in a portent-clouded marriage to Gary Geist, the son of sugar beet farm owners. But as her consciousness about the land grows, so does her sense of agency, and her resolve to escape the marriage.

Human relationships and the environment twine, each reflecting the other’s condition. Erdrich explores the environmental consequences of industrial farming and the possibilities for action when our fate is uncertain.

As weighty as the subject matter is, this novel is a page-turner. After finishing it, I felt like I had read a book without parallel — it stayed with me, coloring my perspective, for weeks.

The Red River runs north along the border of North Dakota and Minnesota into Canada. It is extremely toxic — a key site of danger in the novel — and floods often. Minnesotan geologist Jim Stark said floods in the flat Red River Valley differ from conventional ideas of river surges. “They’re very slow because of the topography, but they inundate a great deal of land,” he said.

The valley’s clay soil is some of the world’s most fertile, however. “I can dig down for two, three feet sometimes, and it’s still black soil,” said Steve Radel. Erdrich stayed at the Radel family’s holiday rental on their Minnesota family farm, Redpath Retreat, while writing the book. The region is responsible for nearly half of U.S. sugar beet production, and is home to the American Crystal Sugar co-op, the largest producer in the country.

“I grew up in the Red River Valley, so I suppose it would be fair to say that I have been researching this book a little at a time, for many years,” Erdrich said. She gathered stacks of documents and interviewed people from different phases of her life about farming.

“While in high school I visited and sometimes helped out friends who lived on farms, or worked in the sugar beet fields, but things have changed considerably,” she said. “I might have a better emotional understanding of why people farm than a practical understanding of how it is done. That did take a lot of research.”

“I don’t see enough fiction about contemporary farming, so I wanted to try.”

Phoebe Farris, a photographer, art critic, and professor emeritus of art and design at Purdue University who is of Powhatan-Pamunkey ancestry, has written about Erdrich. “For Indigenous people, it was always an issue, trying to protect the land and the environment. It wasn’t some kind of new age threat or something that got commodified. What she’s doing, what she’s talking about, we’ve always experienced and tried to live,” Farris said.

Crystal Frechette, Kismet’s mother, works the night haul for the Geists, sticking it out regardless of weather. Erdrich shows the physical labor involved with exactitude: She “worked until her biceps trembled and the back of her neck went numb.”

As Farris said, “Some people are harming the environment. It’s not by choice. It’s the only job we can get.” Environmental damage is not always a matter of agency, but rather of survival.

Meanwhile, Gary, who will inherit the Geist family farm, muses, “The fact was, they weren’t as rich as people thought.” Despite their high output, debt is the reality of running a farm. His mother, Winnie, continues to carry the hurt from the foreclosure of her childhood farm, which her father-in-law bought up.

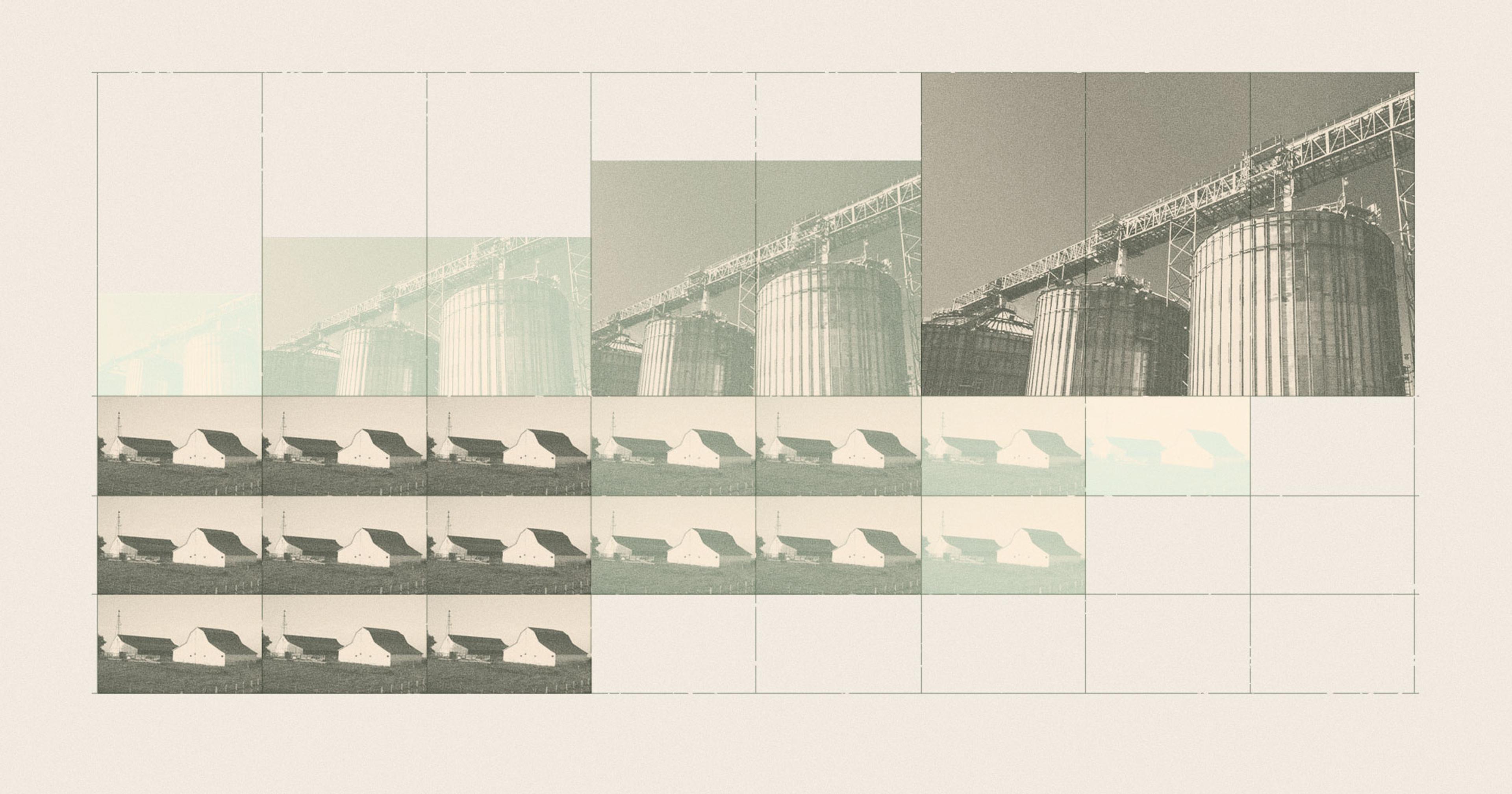

Sarah Vogel, a North Dakotan advocate and former state Commissioner of Agriculture, is the author of The Farmer’s Lawyer, which discusses her experience representing 240,000 small family farms facing foreclosure during the Reagan administration and which Erdrich cites in her acknowledgements. “It was absolutely accurate, the way Louise Erdrich described what happened to her family’s farm,” Vogel said. As in the rest of the country, the number of farms in the sugar beet industry has decreased over time, while their size has increased.

[Sugar beet farming is] “a big cultural thing … it’s really helped a lot of farms through difficult times.”

Still, sugar beet farming is a fact of life in the Red River Valley. Kismet and other characters see a strange beauty in it. Looking out at the Geists’ farm, how “the baby beet plants, coddled in their chemical dust, stretched row after laser row into the shimmer of tomorrow’s heat,” she finds it “exquisite.”

Rob Sip, executive director of the Red River Watershed Management Board, said, “[Sugar beet farming is] a big cultural thing … it’s really helped a lot of farms through difficult times.” His grandmother told him stories of defoliating, digging, and loading sugar beets by hand from nearly a century ago. Sip has helped with the sugar beet harvest almost every year since 1990.

While The Mighty Red is set against the backdrop of the sugar beet industry, gardens are also at the novel’s heart. “There are also gardeners in the book — that’s farming too, personal farming,” Erdrich said.

At the moment she is most lost, Kismet creates a plot of her own. She discovers real soil, with “insect husks, fluffy particles, nutlike crumbs, infinitesimal threads,” while reading Madame Bovary. She resolves to do the opposite of whatever Emma would do, because Flaubert’s heroine poisoned herself and died. “The last thing Emma would have done was put her hands in the dirt and start a garden,” she says. This intention, held onto when everything else is unclear, becomes her guide. She plants cuttings from Crystal’s garden instead and chooses life.

Her realizations crescendo once she visits her friend’s farmstead, which is rewilding sections of its land with native plants, and witnesses a vesper flight. The Radels have been working to make Redpath Retreat a similar oasis, with land put into the CRP (Conservation Resource Program) and RIM (Reinvest in Minnesota), a permanent easement.

Names carry significance in The Mighty Red — it is bold, and a little mischievous, to make your protagonist a gardener named after fate. Aside from Kismet, Crystal is named after American Crystal Sugar. Radel said, “I texted her [Erdrich]. I said, ‘Hey, has anyone else that’s read this book picked up on that little pun?… She goes, ‘Steve, Steve, nobody else.’”

As in the rest of the country, the number of farms in the sugar beet industry has decreased over time, while their size has increased.

Weeds are also more than their name. They symbolize resilience against elimination. Crystal compares her and Kismet’s father Martin’s families to the Lord’s ivy, “a weed ineradicable by human means.” As she eats the nutritious lambsquarters she has grown in her garden, she reflects on how this early American crop has been supplanted by the nonnutritious sugar beet.

“I was raised by parents who operated a large garden so I grew up working in the garden and weeding (and eating some weeds),” Erdrich said. “My grandparents on the Turtle Mountain reservation supported their children with a successful truck garden. My sisters, brothers, nieces, nephews — and as for me I am a slacker.“

She continued, “I am very bad at gardening. Last year my only successful crop was mint — because it is invasive.”

As Erdrich brings readers closer to the present day, she alludes to shifts such as drones and precision technology. These are not framed as at odds with regenerative agriculture: In a dream, Diz sees fields covered in amaranth via a drone.

What most closely links The Mighty Red with our current world is existential risk from climate change. At a book club meeting, the women read Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and debate how the world will end. Winnie points outside at the dirt rising from the sugar beet fields. She says that this is how the apocalypse will happen, because there is no food without soil. Kismet speaks up, saying that the novel is not about apocalypse, but about the love between a parent and child.

The novel acts as a closed circuit, creating balance from its own elements.

These two threads — love and apocalypse — lace through the novel. It maintains the hope that even if we approach the brink, and live amid varying forms of destruction, we can return.

The novel acts as a closed circuit, creating balance from its own elements. At the end, I wondered if Kismet’s world could have been opened slightly more, if returning to the beginning was best for her. But perhaps Kismet is right — what will get us through doom, if not love? The book is about what is to come, but also about what always has been.

From the essential literary ingredients of fate, environment, and love, The Mighty Red charts its own dynamic. While in conversation with the classic novels, it transmutes this literary inheritance to present us with something fresh and true.

“It’s big enough to hold what’s troubling you,” Steve Radel said, about the prairie. “Anything I’m concerned about here, it can be held.”

Perhaps it is big enough to hold our existential crises, both planetary and personal, as well.