Public seed breeders, often academics who work to help farmers and gardeners, are rapidly disappearing. All the while, commercial breeders with patented, expensive seeds are consolidating.

The concept of a seed may seem simple. Collect it from a crop, plant it in the ground, and watch it grow. But it’s so much more than that.

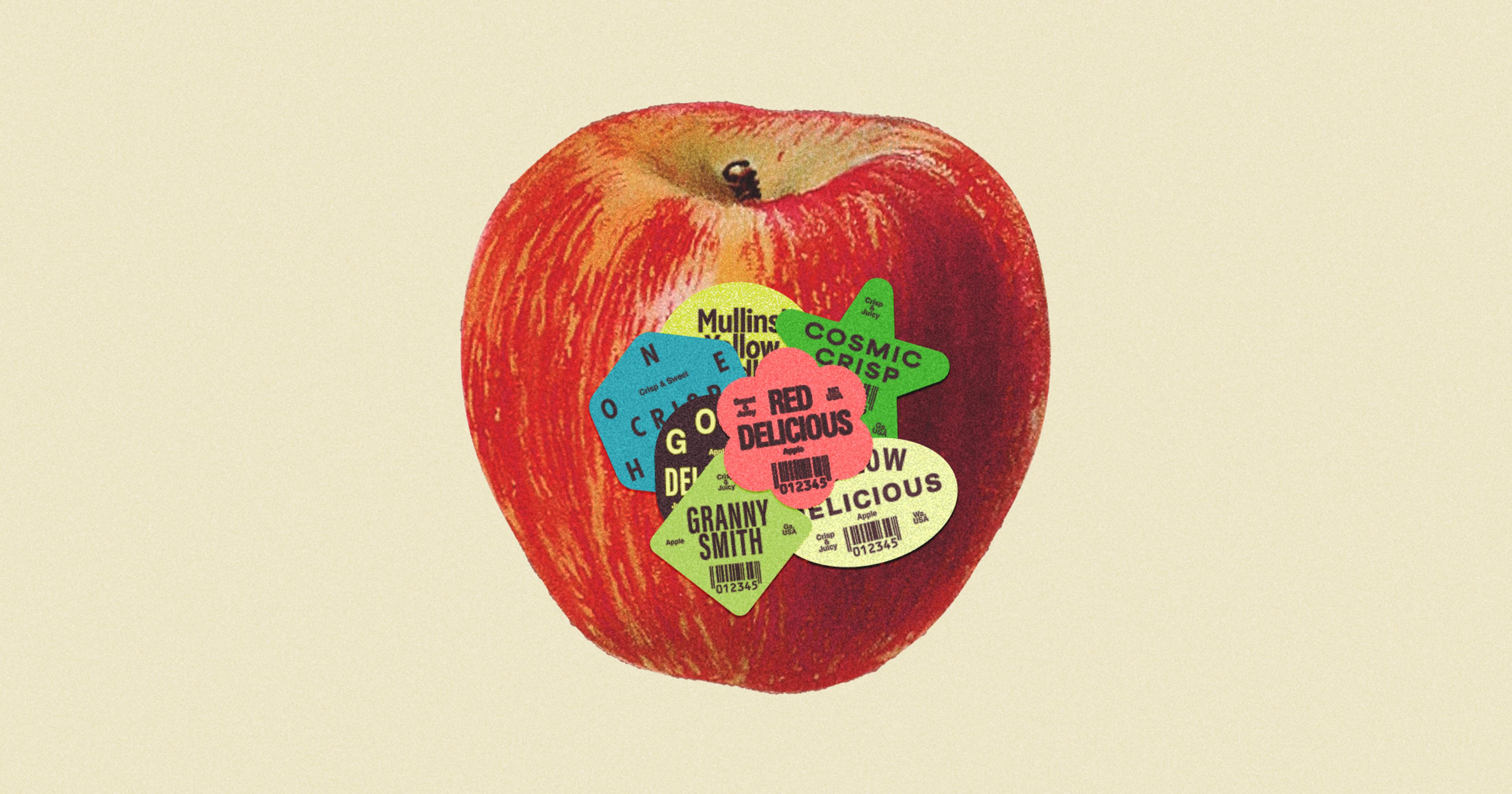

In pursuit of the most bountiful, beautiful, durable, or delicious final product, seed breeders have been adapting and adjusting seed genetics for centuries. And depending on who produces a seed, its genetics may be a) up for grabs or b) tightly controlled intellectual property.

Public plant breeders — often academics at land grant universities — are typically focused on creating plant and seed types that remain in the public domain, meaning the final product is available to any interested researcher or farmer.

But public breeders are becoming all the more rare.

“I’ve witnessed a continuing and accelerating decline in public plant breeding,” said Bill Tracy, a professor in the Department of Agronomy at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who has worked in public corn breeding for four decades.

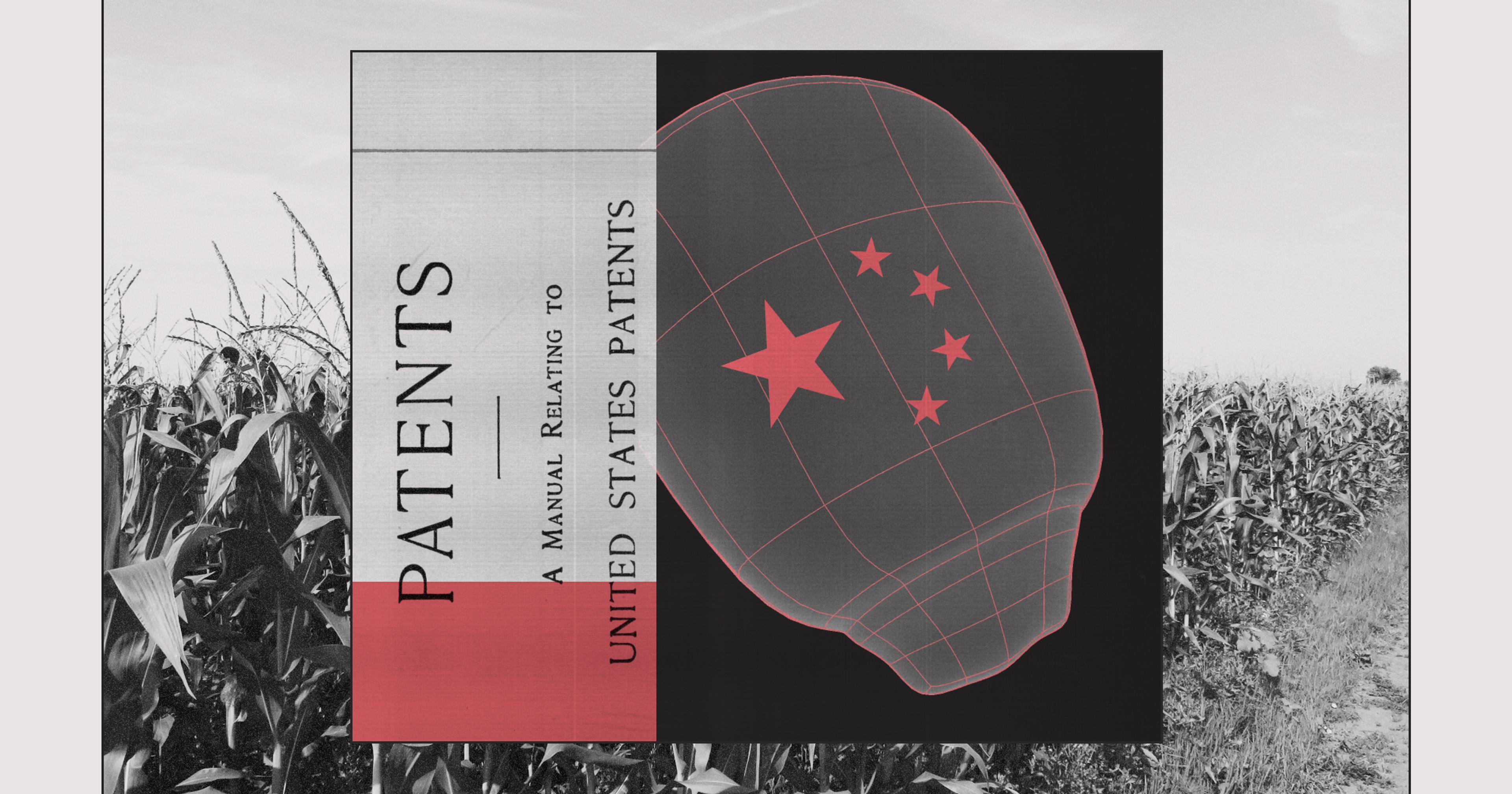

Commercial seed breeders work for large agribusiness companies, researching and breeding seeds for international distribution. The seeds are typically patented — or not allowed to be reproduced and not permitted for use in public breeding programs. This means the farmers growing these crops have no ownership rights over their seeds. Due to patent laws, farmers growing these crops are typically not allowed to collect seeds and use them to replant, which forces them to continue buying seeds year after year.

“Because you can’t save [the seeds] yourself as a farmer, you’re basically passing off any level of seed sovereignty to a corporation,” said Chris Smith, executive director of the Utopian Project, a nonprofit that focuses on crop diversity in the food and farm system. “Those corporations are obviously driven by a profit motive and not the farmer’s interests, necessarily.” And these companies aren’t shy when it comes to suing farmers for breaking patent laws.

Meanwhile the public sector breeds seeds not primarily for financial returns but to help farmers, improve the quality of seeds, and boost the agricultural industry as a whole. This sector of breeding results in returns like lower on-farm inputs, higher crop diversity, protection of natural resources, and more.

And it’s disappearing.

When Funds Dry Up

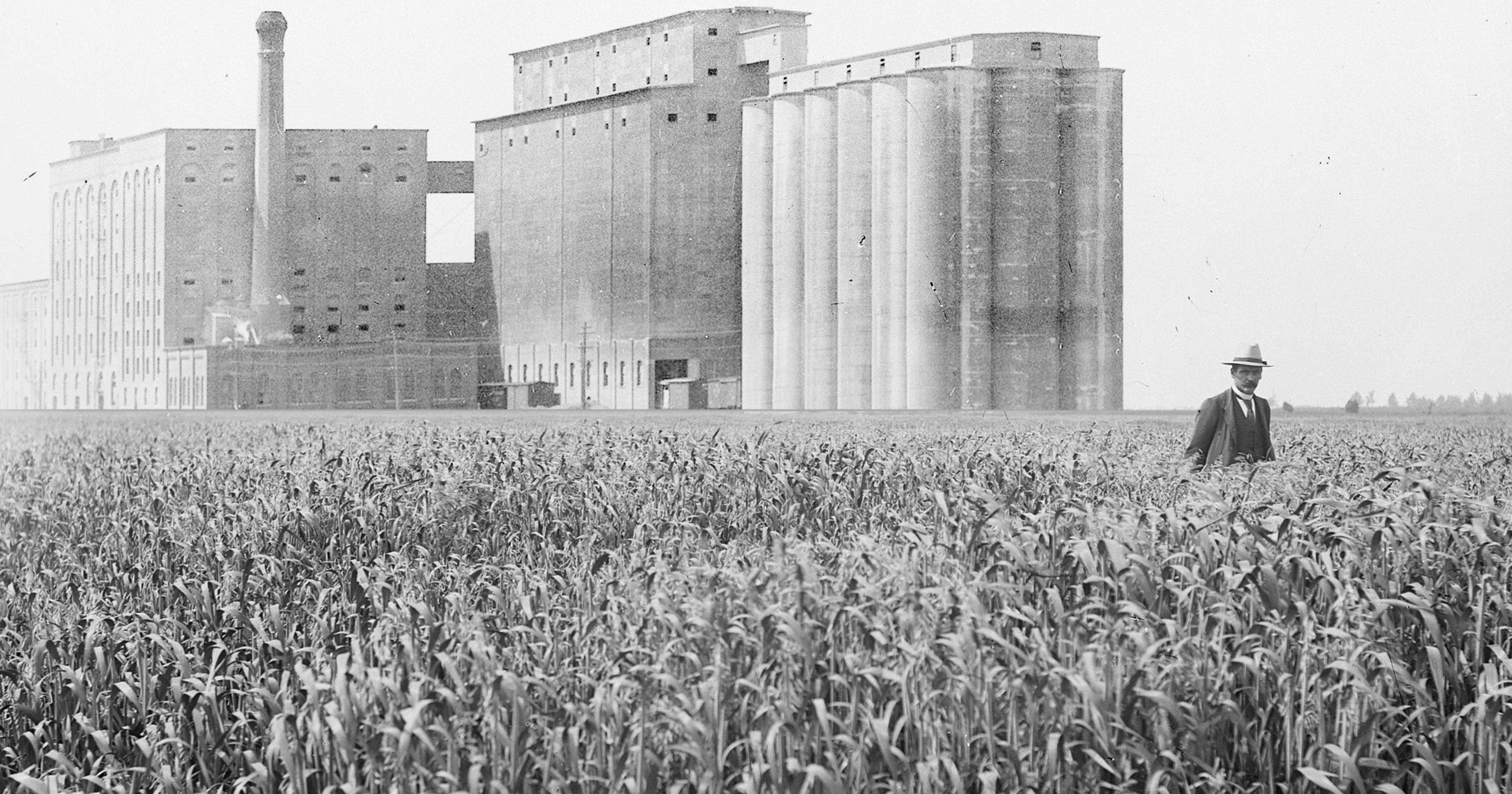

Public plant breeding was once taxpayer-funded and implemented through government programs. That changed throughout the 80s and 90s, when state budgets for universities were broadly reduced. Lower state budgets meant less money to go around, and federal grants became highly competitive. Much of the available grant money was funneled into other agricultural research.

One reason for this is the grant structures. They are often short-term, meaning the grants are awarded on a 1- or 2-year basis — public breeding projects often take much longer to complete. Today’s funding, according to Tracy, has more opportunities than when the situation was at its worst a few decades ago. Still, the inconsistency caused the public breeding sector to take such a hit, it has never fully recovered.

Tracy said that now, even when programs get an influx of cash, the money can often get stuck filling gaps that lack of past funding caused, as opposed to broadening the sector. “We lost large numbers of faculty and when you lose faculty members, you lose people who are training new plant breeders. So that’s one thing. We also lost infrastructure. We essentially have no infrastructure left to start [new projects].”

Another issue: A significant portion of seed breeding program leaders are older (not unlike farmers). When program leaders retire and there is not enough younger staff to take over, the program often ends. Nick Rossi, policy specialist at the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition, who works to advocate for increases in public funding for agricultural research, said, “Across land grant universities, there are significantly less plant breeders on staff.”

Research conducted by Washington State University in 2018 that surveyed 278 public sector plant breeding programs across the country found a 21.4% drop in the programs’ full-time employees — mainly program leaders responsible for designing, planning, managing, and conducting breeding activities.

And that costs farmers.

Commercial Control

With profits on the line, commercial seed companies tend to focus on a final product that results in a high yield. Of course, higher-yield crops benefit a farmer, but other traits that can save farmers cash or achieve sustainability goals — like a crop that requires lower or even no pesticides — often fall to the wayside.

Globally, four giant companies sell more than half the world’s seed supply, according to Rossi, and are generally focused on commodity crops. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) found that across U.S. markets, the top four seed corporations own 97% of canola, 95% of corn, 84% of soybean, 51% of wheat, and 74% of cotton intellectual property rights. The companies control major seed-breeding programs, which then patent and restrict other breeders from access to the crops’ genetics — resulting in fewer and more expensive options for row crop farmers.

“The farmers are not the winners at all. I mean, they’re the survivors, but they’re not the winners.”

Before seeds were commoditized and subject to such strict control, farmers were free to collect, store, and share seeds as they felt fit. They weren’t even always expected to buy their own seeds. When the USDA was first founded in 1862, one of its main jobs was to package and disseminate seeds across the country, free of charge.

Farmers, of course, want their crops to succeed, and seeds that go through the breeding process can become more hardy to weather or pests. But the lack of diversity in commercial seed options and the dwindling number of public breeders leave farmers with fewer choices — and they’re paying more. Seed prices rose 700% over the last two decades for genetically modified (GM) seeds, and around 200% from non-GM seeds.

When it comes to the current seed breeding situation, Tracy said, “The farmers are not the winners at all. I mean, they’re the survivors, but they’re not the winners.”

Charting a New Path

In a recent report by the USDA that addressed the issue of a fair and competitive seed market, the department recommended investment in future public seed breeding. The report encouraged more funding for “public sector plant breeders to work in crops or regions that are currently underserved by the private sector and where innovation is needed for farmer choice and resilience.”

Farmers aren’t the only group with fewer options here. Because private sector breeding often results in patents, public breeders are unable to experiment with most seeds a private breeder produces — leaving some wary.

“The privatization of actual genetic traits is really troubling,” said Smith. “I should be allowed to work with purple carrot genetics without worrying about being sued. And that’s not our current reality, which is really scary to me.”

According to Rossi, in the midst of the tension between the plant breeding sectors, he has noticed a wave of “cooperative grassroots organizations” that don’t necessarily fit the traditional idea of a public plant breeder. These organizations are breeding their own crop varieties for the sake of diversity in seed stock — like the Utopian Seed Project, the Open Source Seed Initiative, and the Ujamaa Cooperative Farming Alliance.

“I should be allowed to work with purple carrot genetics without worrying about being sued.”

Smith explained his nonprofit does some “low-level breeding” work to encourage and offer resources for more farmers in their region (the Southeast) to grow more varieties.

Unlike commercial breeders, the Utopia Seed Project isn’t looking for the highest yield. Instead, they use the diversity of their crops as a buffer for when conditions aren’t hospitable to some crops but may be fine for others — something that will become ever more important both in the face of our changing climate and further consolidation in the seed industry.

Smith said, when it comes to breeding, “Anybody can be a plant breeder, and traditionally everybody was a plant breeder.” To him, keeping plant genetics unpatented and available for breeders to experiment with is important for the future of crops. “There are almost infinite genetic possibilities that seeds could offer. If those genetics get locked off by patenting individual genetic traits or whole varieties, then you’re removing that possibility and part of that plant’s future from a plant breeders toolkit.”