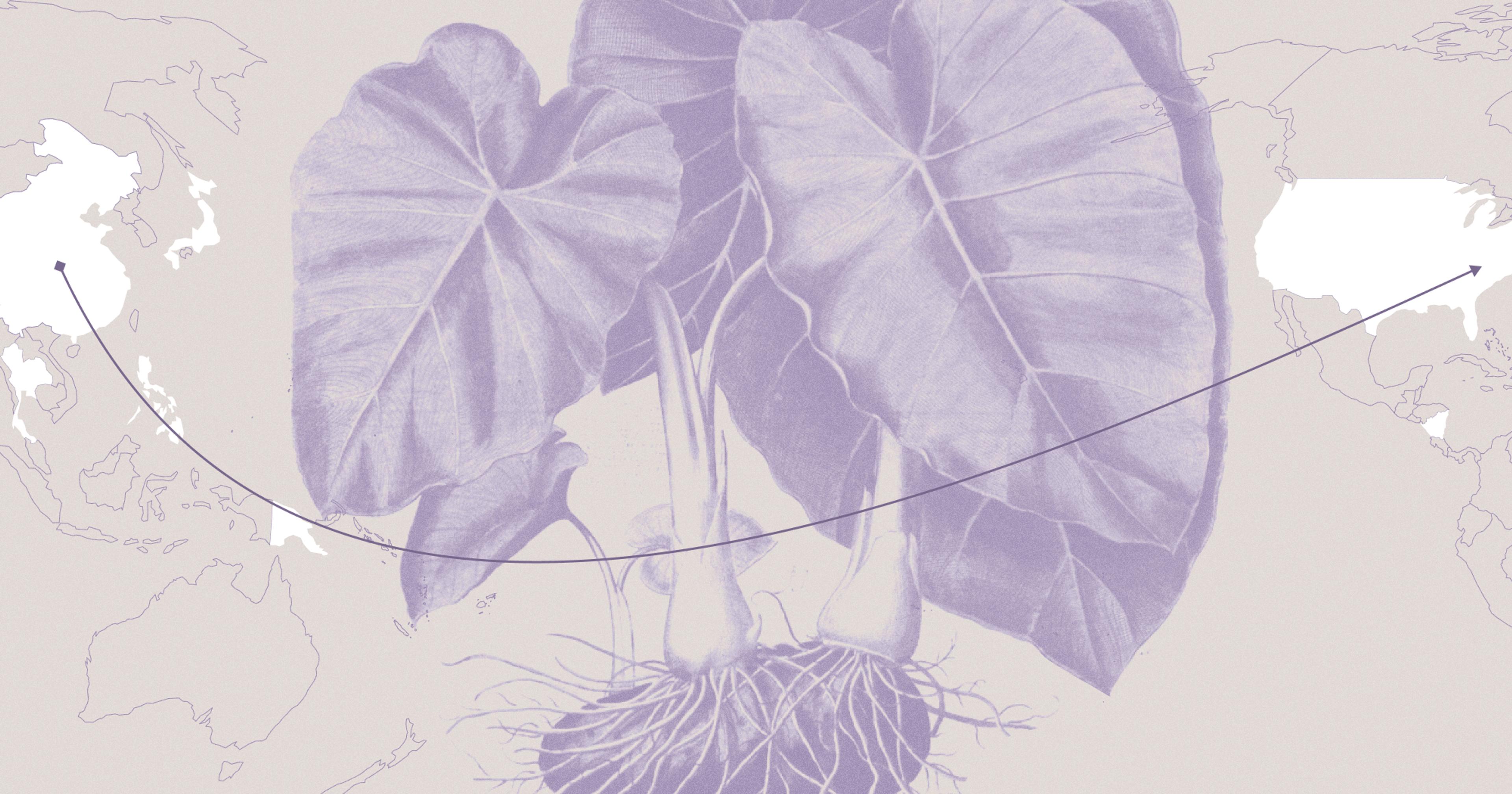

On the Experimental Farm in temperate North Carolina, research growers are cultivating tropical plants like taro, cassava, and chayote — crop options for a changing climate.

On a small patch of land just outside Asheville, North Carolina, experimentation is the name of the game. In recent years, the half-acre plot has yielded typical Southern crops like okra, collard greens, southern peas, and peanuts, as well as plants you’re more likely to find in the tropics, such as cassava, chayote, ginger, turmeric, and taro.

The micro farm, fittingly called the Experimental Farm, is tended by the Utopian Seed Project, a nonprofit dedicated to reviving heirloom crops and increasing biodiversity in Southern agriculture. The organization is doing what many for-profit farms cannot: experiment and test new crops without a guarantee they’ll be profitable. Farmers often don’t have time and money to test out a new crop without knowing they’ll be able to make money from it, and agriculture research at academic institutions is often focused on commodity crop markets. As a nonprofit that receives grant funding for crop research, the Utopian Seed Project aims to help fill this gap.

In addition to honoring the past with seed-saving projects to preserve historically important varieties of okra and collards, executive director Chris Smith has his eye on the future, driven by a curiosity for what might one day thrive in the warming region.

“Every year, it feels like it’s getting a little bit warmer, our seasons are getting a little bit longer. And obviously, that trend is set to continue,” said Smith, author of the James Beard Award-winning The Whole Okra: A Seed to Stem Celebration, who launched the Utopian Seed Project in 2018 with support from local gardening company Sow True Seed. “Yes, we need to mitigate climate change. But we’re pretty stupid if we don’t think about adaptation strategies to climate change, because we’re already there.”

As the length of North Carolina’s growing season has increased, Smith has found that some crops native to the tropics have the potential to thrive there, too. To date, he’s planted arrowroot, cassava, chayote, roselle (in the hibiscus family), taro, turmeric, water chestnuts, and more. The experimental crop trials have shown that what grows as a perennial plant in a tropical region makes a suitable annual crop in another.

Take ginger, for example, which doesn’t grow well when exposed to temperatures below 50°F. The plant might not make it through a cold winter to see another year’s season, but it can certainly grow to maturity in regions with longer growing seasons and then be planted again after winter frosts subside.

Some of the project’s crop trials have yielded better results than others. Taro, a root vegetable that’s a staple in many African and South Asian cultures, is especially promising. “In this region, you can grow it with less externalized inputs. It doesn’t need as much irrigation, fertilizer, or pesticides. It doesn’t have any pest predators in this region at the moment … From a farmer’s perspective, it’s pretty much as easy to grow as potatoes,” said Smith. Taro is also a versatile ingredient that can be prepared in similar ways to a potato, a key factor for its future success. “Anything you can do with potatoes you can do with taro.”

“Yes, we need to mitigate climate change. But we’re pretty stupid if we don’t think about adaptation strategies to climate change, because we’re already there.”

On the other hand, cassava (often referred to as yuca) seems to want just a slightly longer growing season than what’s currently available in western North Carolina. All the batches Smith has grown simply do not grow large enough to be a viable food crop. “If we just had another month in our season, cassava would be a perfect crop,” he said. “It’s just agronomically not quite making sense for us yet.”

Still, Smith says it’s a category of crops worth exploring. For one, North Carolina’s demographics are changing. According to the most recent Census, foreign-born residents now make up 8% of the state’s population, and have brought rich cultural food traditions with them. Between 2010 and 2020, North Carolina’s Asian-American population grew 64%, according to data collected by the UNC Asian American Center.

“A spin-off benefit of [tropical crops] is that it really creates niche opportunities for traditionally underrepresented farmers, immigrant farmers, African-American farmers. The people that get really excited about taro are people who have experienced it because they’re from West Africa, or the Caribbean, or from Asia,” said Smith, “and that gives an opportunity for the farmers to supply those restaurants … It doesn’t have to be limited to that, and I don’t think it should be limited to that. But certainly, they’re the first people who respond positively to it and that could be really useful.”

Additionally, Smith believes that it’s important to start growing these plants now in order for them to be regionally adapted by the time there’s a need to plant them more widely. “It’s going to be much harder to grow the crops that we traditionally grow, and we’re going to want other crop options for a changing climate,” he said.

While North Carolina is considered a temperate climate, changing weather patterns already show the state is getting warmer, wetter, and more humid. “We’re still temperate, we still have seasons,” explained David Suchoff, alternative crops extension specialist and assistant professor in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences at North Carolina State University. “But that being said, when you look at our summers, and our soils, we’re almost kind of a subtropical system … we can grow crops almost year-round.”

“It’s not like an iPhone, where you can just have a marketing campaign and release it. It’s agriculture, so it’s slow.”

Academic researchers like Suchoff are similarly looking for alternative crops to introduce to North Carolina farmers, many of whom can no longer depend on tobacco for a steady, reliable source of income. “We want to look for crops that are resilient, crops that have the ability to withstand a lot of the seasonal variation that is becoming a lot more prevalent with climate change,” he said.

One of the alternative crops that Suchoff sees great promise for is sesame, which is widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical parts of the world. Currently, only a small percentage of sesame is grown in the U.S. — North and South America combined account for a measly 4.3% of the world’s supply — and almost all of it is grown in Texas and Oklahoma. It’s low-input and highly drought-tolerant, a crop that could diversify income sources for commodity farmers who already grow corn and/or soybeans. “There’s a huge [global] demand for sesame that’s not being met,” he said. “There’s a lot of interest in trying to expand production into the Southeast, because there are a lot of similarities and aspects of our climate that are a good fit for that crop.”

Finding a new crop that’s suitable for a region’s changing climate is the first step. Integrating it into the local food system is the next hurdle, and arguably the most important part. After all, without demand for a crop, what’s the point in growing it? Just because taro or arrowroot or water chestnuts grow well in North Carolina doesn’t necessarily mean there will be buyers.

“It’s not like an iPhone, where you can just have a marketing campaign and release it,” said Smith. “It’s agriculture, so it’s slow. There needs to be a supply chain, and it needs to be ongoing. It’s complicated.”

That’s why the Utopian Seed Project spends as much time building a network of cooks and chefs interested in the experimental crops as they do growing them. With taro, for example, the organization conducted public taste tests and dinners, as a way to assess the tuber’s viability and popularity among consumers. The taro chips, whipped taro, taro hash browns, and steamed taro that were served received positive feedback. The organization also partnered with the student farm at Elon University, which grew taro and supplied it to the college’s dining program.

Of all the plants being trialed in rows on the Experimental Farm, Smith is especially psyched about the future of taro, which he hopes will serve as a model for how to grow tropical crops in a temperate region and successfully integrate them into the food system in a smart and meaningful way. “It’s definitely got the potential to have the culinary businesses excited about it, consumers wanting to eat it at home, and farmers being able to make money from growing it,” he said. “I don’t think it’s going to become a cash crop, but it can become a profitable crop.”