North Carolina’s tobacco production has been declining for years. A new specialty crop is emerging, but some growers are wary.

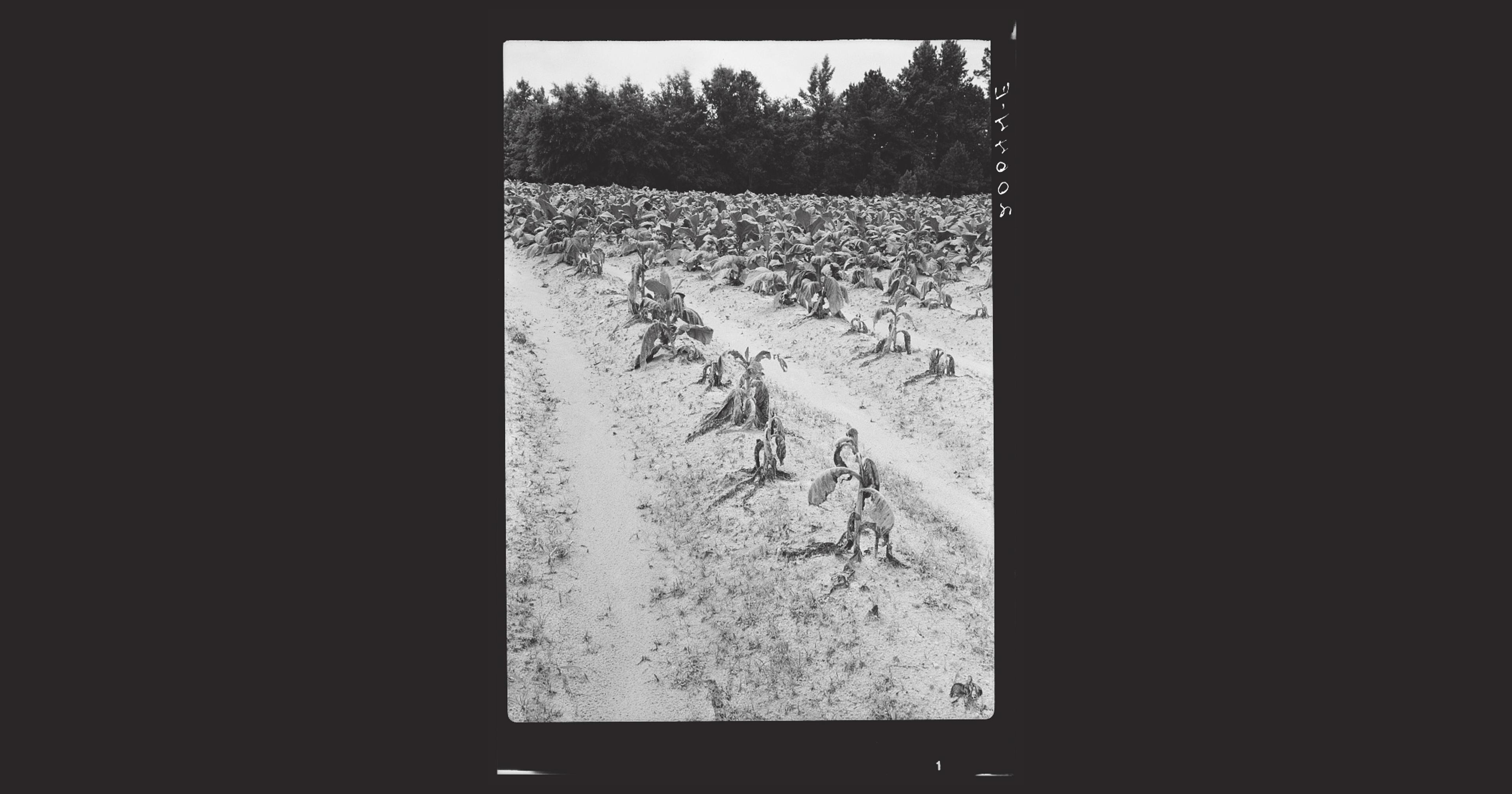

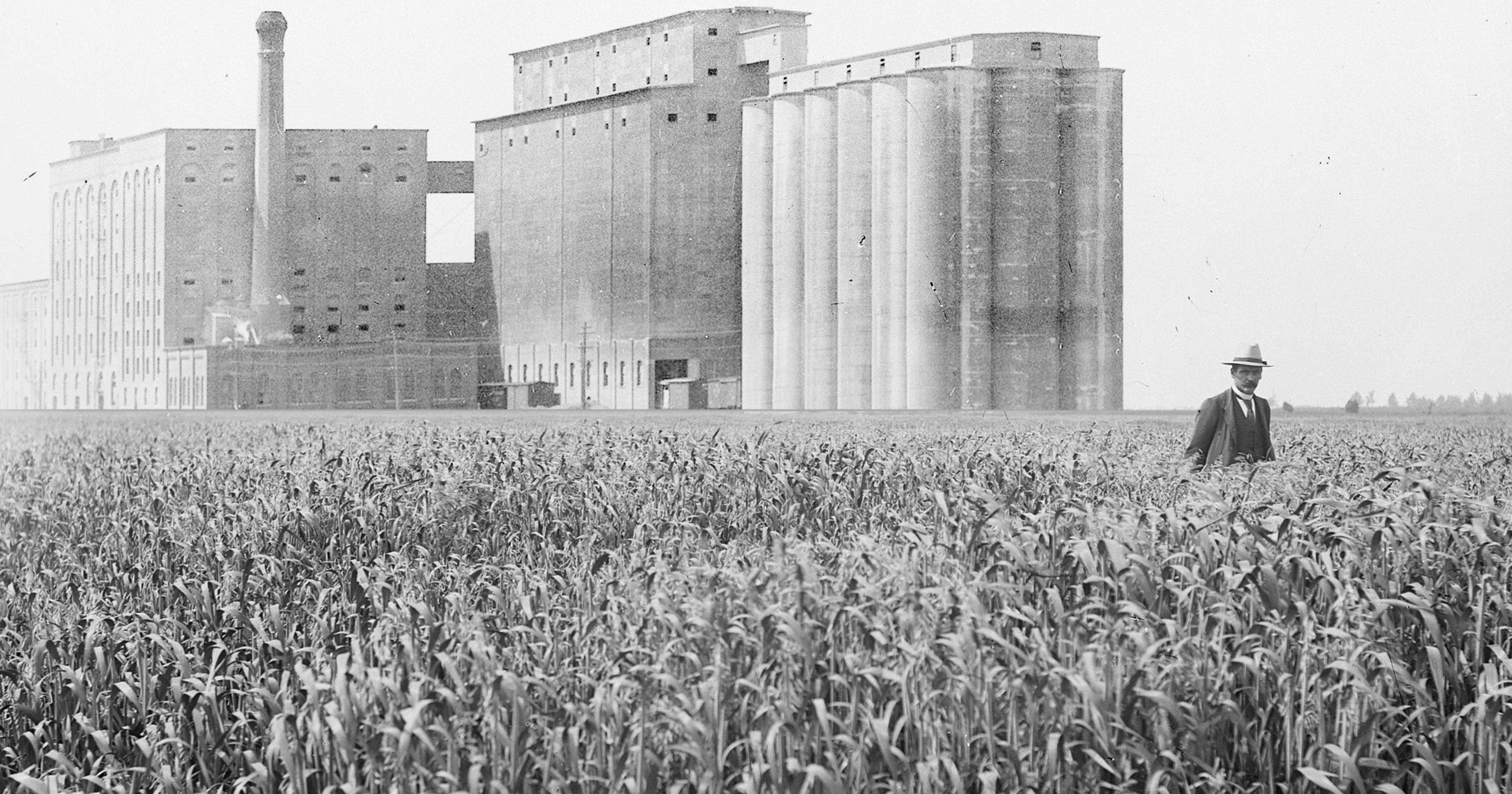

In its heyday in the 1950s, North Carolina grew nearly one billion pounds of tobacco, a profitable crop that its farmers continued to rely on for decades. But even as the state’s production levels reached an all-time high, the American tobacco industry was already beginning its decline. It began with the emergence of health-related articles warning against the dangers of smoking cigarettes in 1957, followed by the first Surgeon General’s report on smoking and health in 1964, which held cigarette smoking responsible for a 70% increase in the mortality of smokers over non-smokers.

The report served a devastating blow to North Carolina’s economy, which was primarily fueled by agriculture — most notably tobacco. As smoking rates have fallen 68% among adults since 1965, so has the planted acreage of flue-cured and burley tobacco, which account for more than 90% of all U.S. tobacco production. Last year, 116,000 acres of tobacco were harvested in the Tar Heel State, totalling nearly 250 million pounds. That’s a lot of tobacco, especially when you consider the fact that there’s between 0.65 and one gram of tobacco in a single cigarette.

And yet it’s a small fraction of what the state once grew.

“It’s been my livelihood my entire life … and it’s been real important to our part of the world,” said Mack Grady, a third-generation tobacco grower in Seven Springs, North Carolina, who doesn’t use any tobacco product himself. “It’s a long-lived crop, but it’s dwindling.”

North Carolina is still the nation’s largest tobacco producer, followed by Kentucky and Virginia. But tobacco is no longer the most profitable crop, and the landscape is rapidly changing. Drive through almost any county in the central and southern parts of the state, and you’ll see formerly abundant tobacco farms that have been developed into housing subdivisions, shopping centers, and wide-laned expressways.

In an effort to keep their farming operations afloat, hopeful farmers like Grady are trialing a new tobacco crop — cigar wrapper tobacco leaves. Known as Connecticut broadleaf, this type of tobacco is traditionally grown in areas of the Connecticut River Valley, which stretches from Hartford, Connecticut, across the border into Massachusetts, including parts of southern Vermont. Broadleaf tobacco is a relatively new crop to North Carolina, planted for the first time in 2018, but farmers and researchers alike are excited about its potential — and long for a solution that doesn’t involve selling their land to developers.

“Our farmers are competing not only in the commodity that they’re growing, but also they’re competing with the housing market and development,” said Will Strader, N.C. Cooperative Extension director for Rockingham County. “So they’ve been hit from multiple directions.”

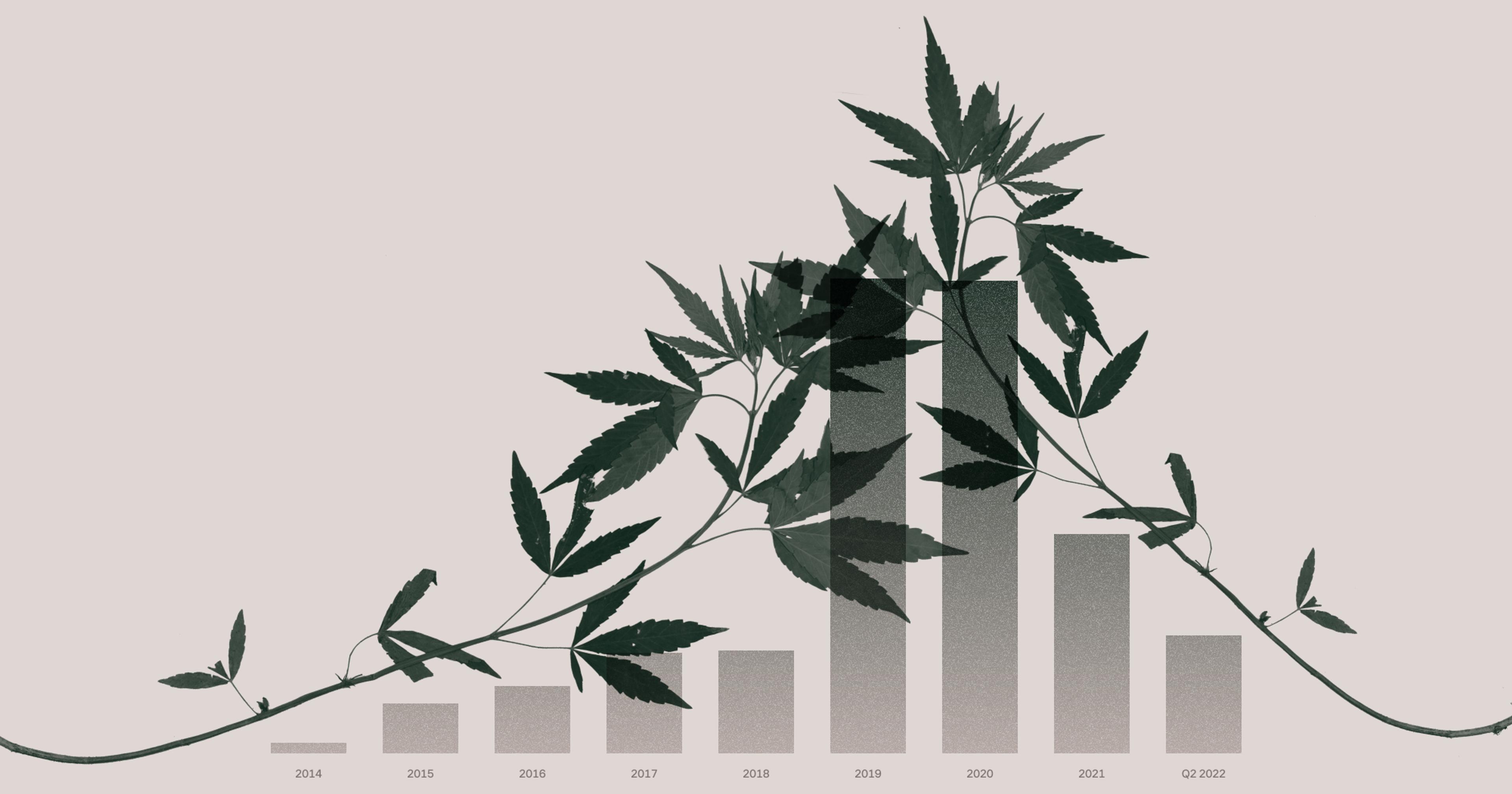

Could growing broadleaf tobacco help lift these farmers up? Unlike cigarette tobacco, the market for broadleaf tobacco is still strong, correlating with cigar sales that have steadily increased since 2015. For many cigar enthusiasts, high-grade broadleaf tobacco is among the most prized leaves used to make dark maduro cigars. But tobacco farms aren’t as prevalent in the Connecticut River Valley as they once were, causing a supply issue that has been further compounded by several consecutive bad growing years.

“It could potentially be even more profitable than the tobacco traditionally grown in the state.”

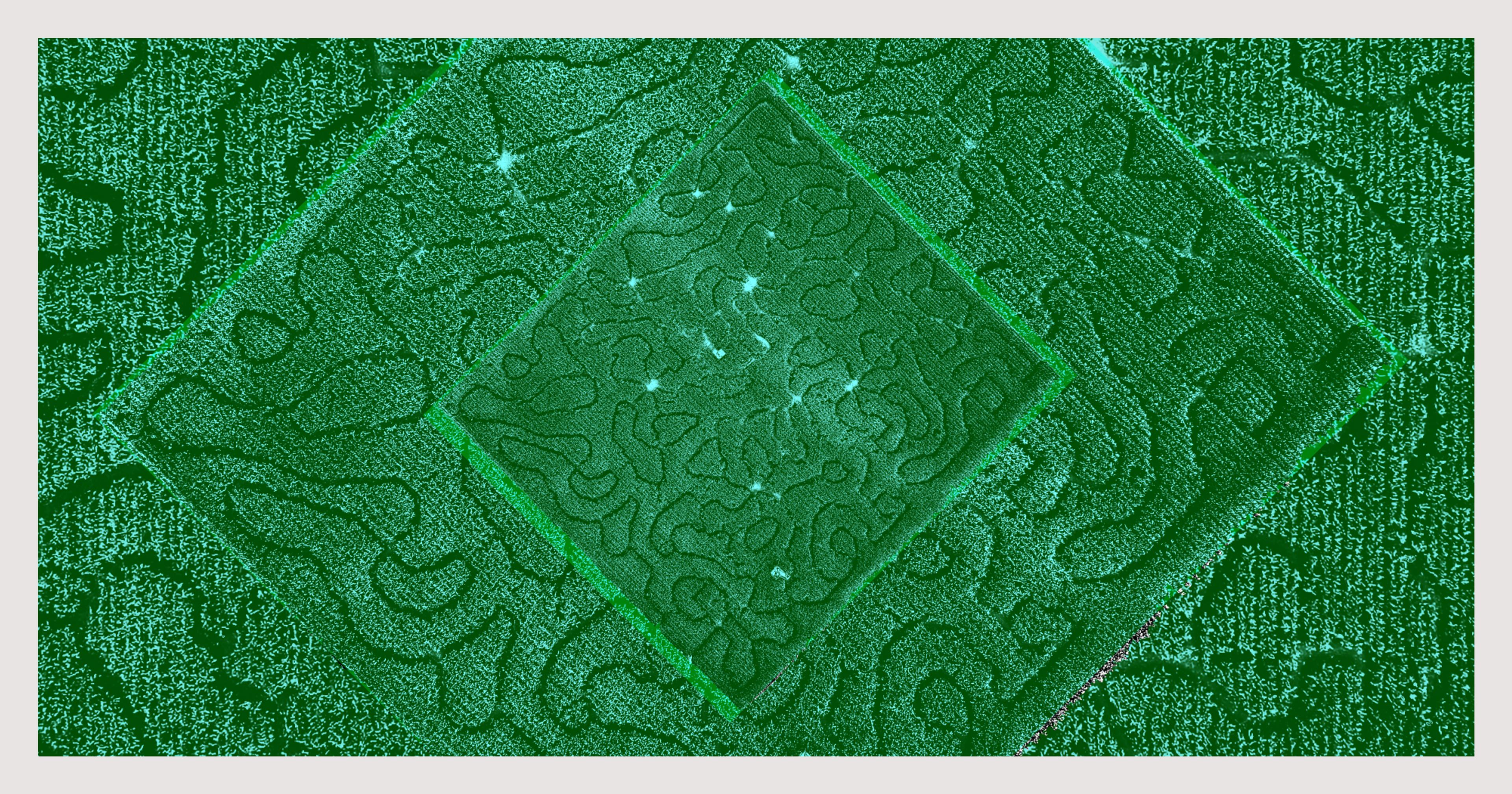

Tobacco growers in other states are now facing an opportunity to fill the gap. “There’s more [broadleaf] tobacco needed than the existing grower base could produce. North Carolina, as well as Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee, have all picked up on that and tried to see if this is a style of tobacco that can thrive here since we’re all familiar with different styles of tobacco already,” said Maggie Short, a crop and soil sciences doctoral student at North Carolina State University who’s working to develop nitrogen and potassium fertility recommendations for the new-to-N.C. crop.

“It could potentially be even more profitable than the tobacco traditionally grown in the state,” said Short. But first, she and other researchers need to learn how the new crop — which wasn’t bred to thrive in North Carolina — will react to disease and pest issues in a southern climate.

Grady harvested his first acre of broadleaf tobacco last year, a decision he made after realizing he wouldn’t need to purchase any new equipment to do so. “You use the same planter, the same plow, the same tractor. You can start growing it without a lot of new expenses because you’ve already got the infrastructure in place,” he said.

That said, unlike its flue-cured and burley cousins that are grown for cigarettes, cigar wrapper tobacco requires heightened management and care. A more labor-intensive crop with plenty of risk involved, its leaves have to be perfectly intact — no holes bitten by pests, no sunburn, no blemishes, no rough handling that could lead to tears. “One caveat is that it’s going to be a high-input crop … It takes a lot more tender love and care to grow this crop than other styles of tobacco that we’re used to,” said Short. “We really have to handle it with a velvet glove from planting all the way to curing, not just harvest but beyond that.”

“It takes a lot more tender love and care to grow this crop than other styles of tobacco that we’re used to.”

Short is no stranger to the tobacco industry. Her dad and uncle farmed tobacco in Guilford County, where it was first planted in 1610, until 2004, when the Tobacco Transition Payment Program (colloquially referred to as “the tobacco buyout”) allowed farmers to receive federal funds through the USDA with the goal of helping them exit the dwindling industry. After that, the brothers transitioned the family farm into mostly hay production and had to find off-farm jobs to continue to support their families.

Now, she’s hoping to give other farmers a different fate. “With the decline in tobacco production in North Carolina, we do see some farmers looking for alternate sources of revenue, and we definitely see [broadleaf tobacco] as an opportunity for our growers to not only diversify farms, but hopefully find a profitable crop, maybe more so than other things they might be growing,” said Short.

Not every tobacco farmer is onboard. After watching what happened with the failed promise of hemp, some growers are wary to jump on the broadleaf bandwagon. “Years ago, we saw the hemp boom come and go. And there were a lot of growers that tried that,” said Short. “Quite honestly, I don’t know that there’s any farmers in North Carolina growing hemp anymore.”

Perhaps learning lessons from the hemp bust, researchers and extension agents aren’t recommending farmers go all-in on broadleaf tobacco production. Instead, they’re encouraging farmers to plant a small amount to start while still farming the flue-cured and burley varieties they know well. “It’s not going to replace flue-cured completely. Hopefully it will help them supplement and provide another source of income,” said Strader. “It’s not gonna fit into every operation because of the intensive management that’s involved, but it is a good alternative for certain growers.“

It’s too early to tell if introducing cigar wrapper tobacco to farms will be a boon or a burden. “There’s moving variables, like any business, and I can’t say that it’ll still be here in 20 years,” said Grady. But one thing is certain: “People are still gonna smoke cigars and cigarettes all over the world.”