New research has found that miniscule pieces of plastic dotting cropland could be hurting the photosynthesis process and leading to lower yields.

When Eric Cates, owner of Cates Family Farm in Spring Green, Wisconsin, monitors his cows, he’s carefully eyeing them for one particular transgression: to ensure they don’t munch on any plastic garbage thrown from driver windows.

“I’ve seen bags of chips and plastic bags drifting into our farm,” said Cates, “and we can’t let them eat anything that they come up on. We don’t want that plastic in their system.”

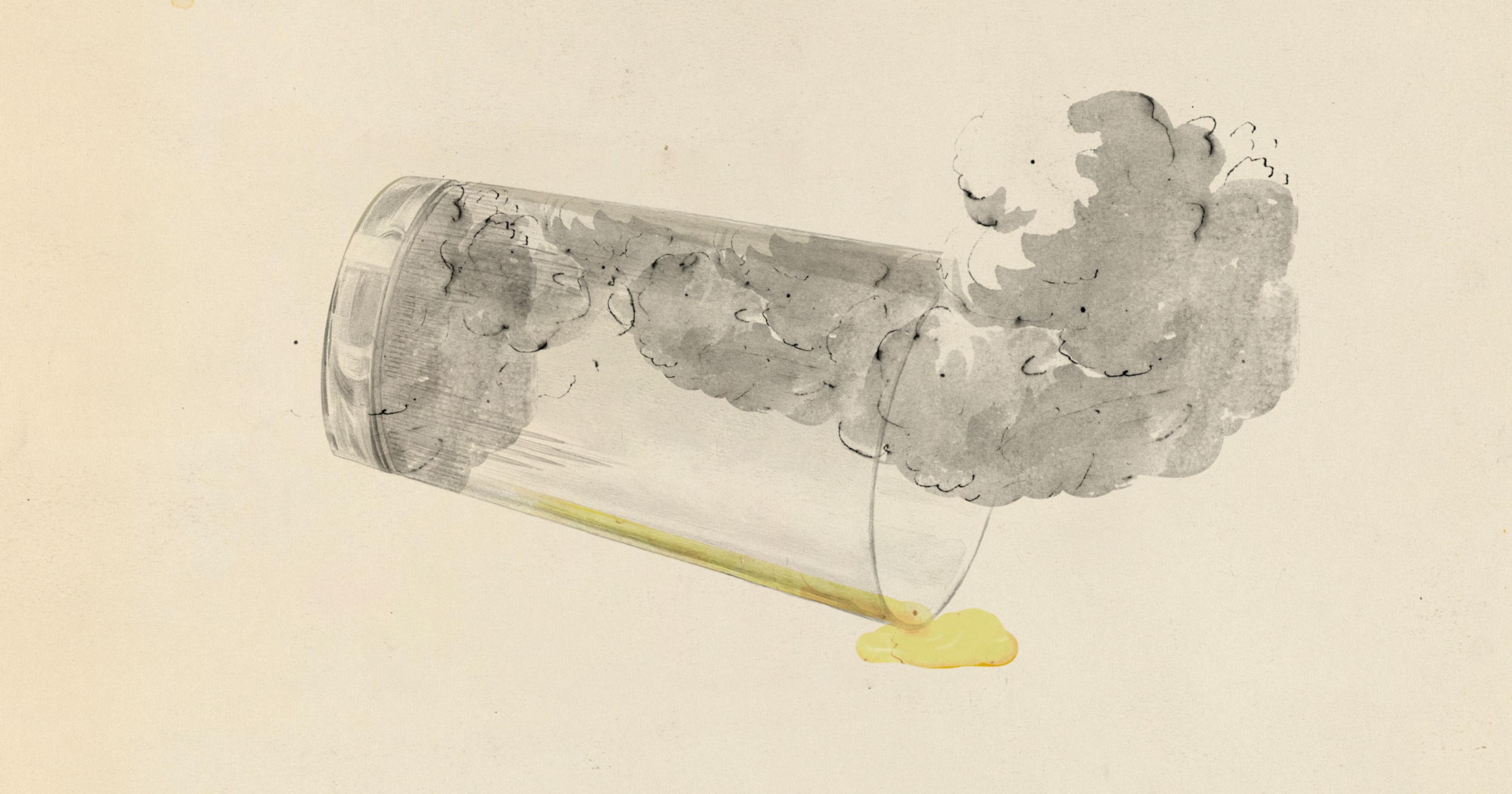

New research has found that farmers might be up against a more difficult form of plastics to find that can hurt their yields: Microplastics are miniscule fragments of plastic products that have been detected almost everywhere on Earth, from Antarctic sea ice to human brains.

Most research on microplastics has focused on its potential relationship to human health but now more studies have found a relationship between these tiny plastic pieces and plant health.

A 2024 report discovered how this crisis has disrupted the photosynthesis process across a wide swath of crops, including soybean and corn. The study from Ninjaing University in Japan, published in National Academy of Sciences USA, noted how microplastics coverage reduces the photosynthesis of terrestrial plants by about 1 percent, and by about 7 percent in marine algae.

The study also found that with the current rates of worldwide plastic production and microplastics exposure, farmers may see a 4 to 13.5 percent yield loss per year in staple crops such as corn, rice, and wheat over the next 25 years.

The researchers added that a 13 percent decrease in “environmental microplastic levels could reduce photosynthesis losses by approximately 30 percent … and the study emphasizes the importance of incorporating plastic pollution mitigation strategies into broader sustainability and food security initiatives.”

“The impact of this study is very substantial,” said Richard Thompson, professor of marine biology at the University of Plymouth and who, in 2004, coined the term “microplastics.” He wasn’t involved in the recent research.

It is “almost impossible to remove [microplastics] from the environment, which is why it’s essential to reduce their use straight from the source.”

He added how microplastics are so nano-sized, it would be “almost impossible to remove them from the environment, which is why it’s essential to reduce their use straight from the source.”

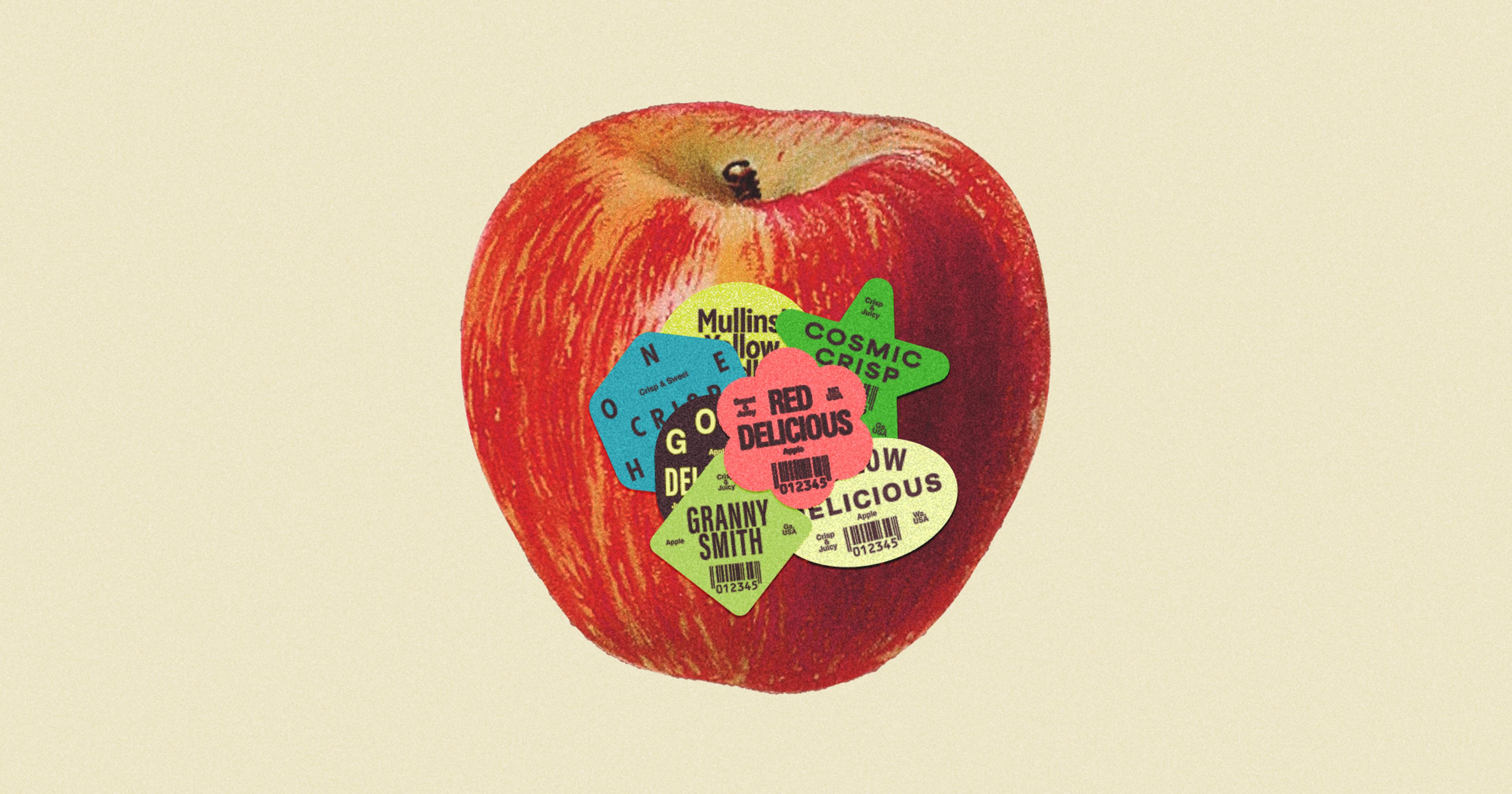

Both Thompson and the Chinese study point to several pathways for microplastics to infiltrate crops: Heavy use of plastics in textiles and cosmetics leads to treatment plants pumping out sludge that is often used in farmland as a nutrient enrichment. Mulch films and fleeces to protect crops are largely made from plastic. And airborne microplastics can shuttle through the air from, say, car tires on nearby roads.

The latter pathway can be especially harmful to human health. A report from the Center for International Environmental Law noted that “microplastics often have large specific surface areas and are predominantly hydrophobic, meaning they repel water. These characteristics make airborne microplastics a ‘Trojan Horse’ capable of hiding and carrying harmful substances inside the animals or humans who inhale, absorb, and ingest them.”

Microplastics don’t just hurt a crop’s growth but also its flavor. A 2023 study from Agricultural University in India also found stunted growth in crops, such as tomatoes, peppered with microplastics. Study author Periasamy Dhevagi said these particles dwindled seed germination rates, particularly at higher concentrations. She added, “It was observed that a concentration-dependent negative [meaning, if the observed area was high in microplastics concentration] impacts the physiological, biochemical, growth, yield attributes and fruit quality of tomato.”

Most significantly, microplastics in the studied crops showed “metabolic disturbances that can impair growth and reduce resilience to environmental stresses,” Dhevagi said.

“The impact of this study is very substantial.”

Dhevagi urges for more research into an area of agricultural science she believes is sorely ignored. “The possibility of microplastics entering the food chain raises worries regarding food safety and human health,” she said. “Addressing this issue needs a collaborative effort among politicians, academics, and the agricultural community to establish sustainable practices and policies that reduce microplastic contamination in agroecosystems.”

Thompson, a specialist in microplastic pollution’s impact on marine life, is hopeful that UN negotiations between 180 countries “who realize how dangerous microplastics can be,” is close to securing a binding treaty, despite numerous meetings over the past five years.

Most recently in December 2024, a group of oil and gas producers led by Saudi Arabia, Iran, Russia, and other Gulf states, opposed capping plastic production outlined in the treaty, insisting the regulations should focus solely on plastics waste management.

With plastic production still rising — projected to nearly triple by 2060 — Thompson is anxious the spread of microplastics in both agricultural and marine ecosystems will gain too much momentum to be reversed. He also believes a particular scientific challenge has blunted the treaty’s progress.

“If there’s enough outrage out there about microplastics covering so much farmland, then yeah, I definitely think these ideas could gain traction.”

“Many countries still want evidence microplastics can be dangerous to human health, and studies have only been able to prove association, not causation, because we can’t do studies on human subjects,” Thompson said.

Still, he maintains, the microplastics found on plants could end up in the food we eat. “We already know this happens with other foods including fish, and questions are in what concentration and how harmful are they.”

Some farmers are not taking any chances with how microplastics may be ending up on their land. For now, Cates will still be taking a hands-on approach to keeping his family farm as plastic-free as possible. He’ll continue picking up Doritos bags and beer cans flung near his land, and he’ll also quickly trash the plastic binding wound around his hay bales.

He pauses thoughtfully when asked if he thinks these new studies on microplastics will move the policy needle in any way. Two beats. Then he replies, “If there’s enough outrage out there about microplastics covering so much farmland, then yeah, I definitely think these ideas could gain traction.”