Bullied by blight, the filbert has long failed to find a home on farms in the eastern U.S. After decades of research, its arrival is imminent.

When Tom Molnar was a young man in the late 1990s, he visited an orchard that gave him something to dream on.

On a farm in south-central Pennsylvania, George Dickum, nearing his 80s, was the proud keeper of a 30-year-old hazelnut orchard. Packed with fruiting trees, it was a land out of time. All across the eastern United States, hazelnuts had been cut down by Eastern filbert blight, or EFB, an endemic disease that chokes life from a tree and prevented a domestic industry from taking root. As if by magic, the trees in Dickum’s orchard had evaded the blight.

For Molnar, then early in his tenure as the head of Rutgers University’s hazelnut breeding program, it was at once inspirational and worrisome. Dickum’s hazelnuts showed the promise and potential of a new crop for northern growers — a low-input, high-value, nut tree that could enhance soil health and diversify farmlands sustainably. That is, if someone could protect it from disease. But, Molnar knew, nobody had yet done that; Dickum’s trees were susceptible. Their survival was predicated on isolation from other orchards. Someday the wind would blow the wrong way, bringing deadly spores from neighboring land, and the orchard would collapse.

“This poor guy,” Molnar said, “was going to lose everything if blight made it to his farm.”

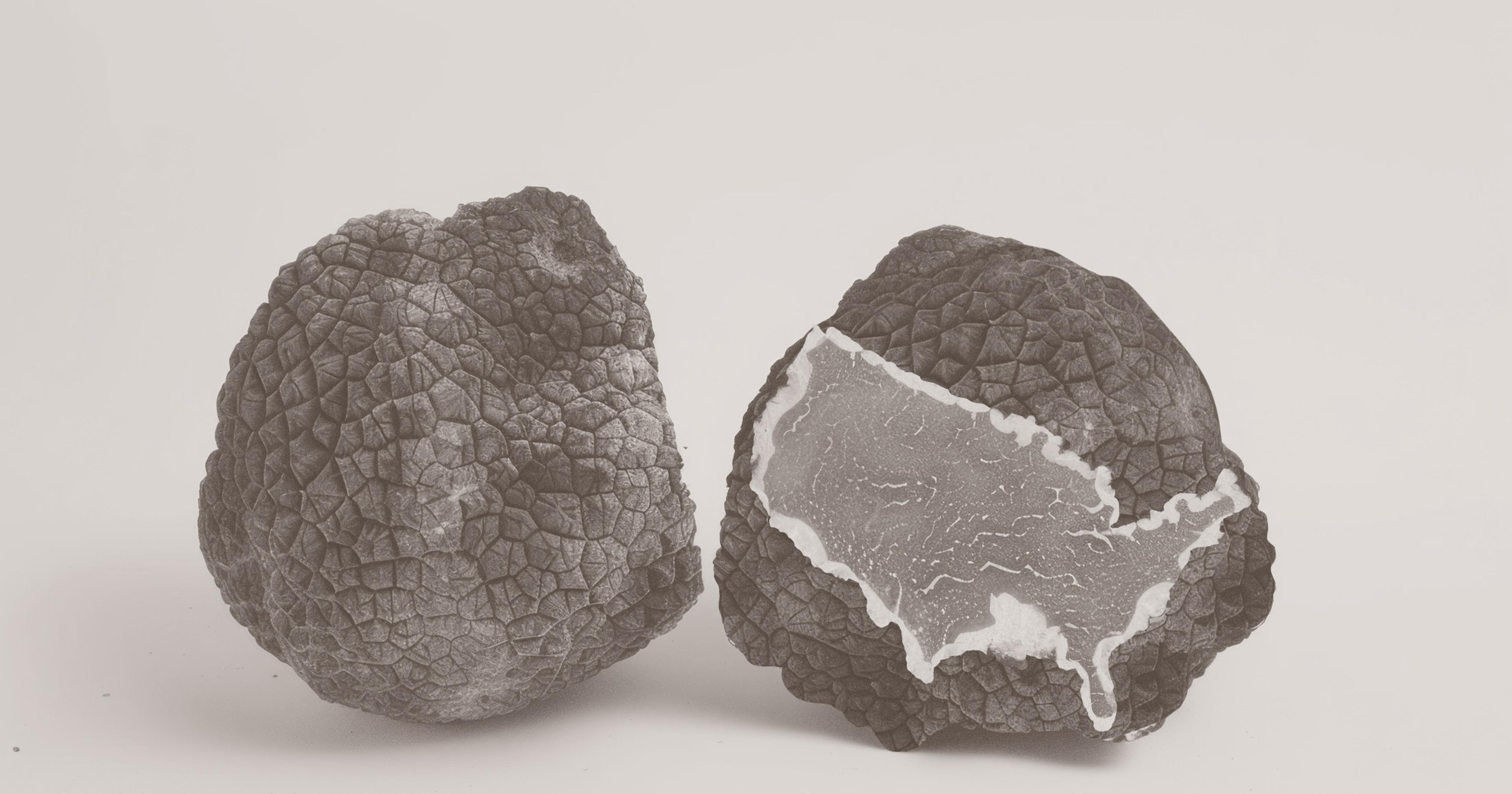

Carried on the wind or splashed about by rain, EFB spores infect a tree at bud break, when young, vulnerable shoots emerge. Some 16 months after infection, cankers begin to grow — sunken, dark brown, football-shaped patches that will release their own spores in time and spread from a tree’s canopy down to its trunk. By the time the cankers have reached that far, the tree’s fate is certain. The fungus girdles the vascular tissue; limbs die, leaves brown and shrivel. “It’s a slow, painful process,” hazelnut breeder Shawn Mehlenbacher said.

But now, after nearly three decades developing a way for farmers to overcome EFB, Molnar has finally got something to show for it: a collection of four cultivars, released in 2020, that can withstand even the intense pressure on his New Jersey research farm, where numerous strains of the blight are present. Molnar, now 47 and as driven as ever, has planted tens of thousands of doomed trees in search of these resistant varieties. And there are more in the pipeline, as well as a small but growing circle of farmers, chefs, and chocolatiers eager to see his vision made real.

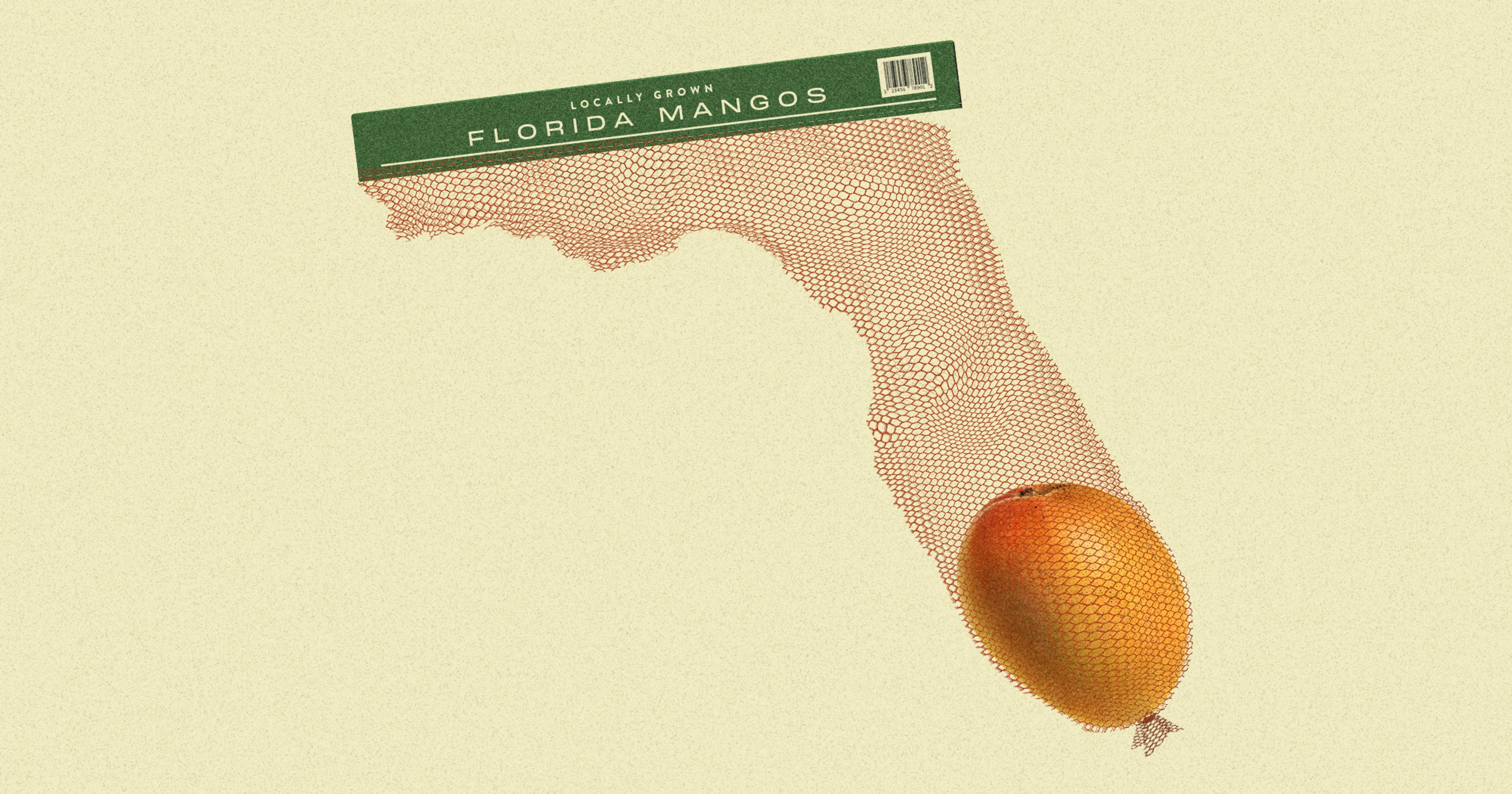

Today, a hazelnut industry stands ready to rise in the eastern U.S., just as a new strain of EFB threatens 100,000 acres of trees in Oregon that represent nearly all of this country’s contributions to the $3.5 billion global hazelnut market. The U.S. ranks third in the world in production behind Turkey, which grows more than 70 percent of the nearly 600,000-ton global supply, and Italy. But it’s the only country where EFB lurks, making it necessary to breed resistance. There are now 150 acres of sturdy, resistant hazelnuts planted across the Mid-Atlantic, Molnar said, and the foundation for something much bigger to develop.

“I’ve been all over the world looking at hazelnuts just to see if we can do it here,” he said. “And I’m finally seeing that we can. It’s actually happening.”

The Slow Work of Selection

On a Friday morning in late August, a wash of dark clouds hangs over Rutgers’ Horticultural Farm 3 in East Brunswick, just a stone’s throw from the cars whizzing by on the New Jersey Turnpike. The first cool air in months suggests fall is on the way, and the hazelnuts pooling around the base of the trees seem to sense it. Vise-grip in hand, brown hair tucked behind his ears, Molnar darts between selections of Corylus avellana, the European hazelnut, habitually cracking open shells. In a trim scarlet t-shirt over boots and cargo pants, he moves and speaks with the type of enthusiasm that usually wears off after all this time.

“Very few people have ever tasted a fresh, high-quality hazelnut,” he said, handing over a batch he just roasted. “Most people don’t know how tasty they actually are.”

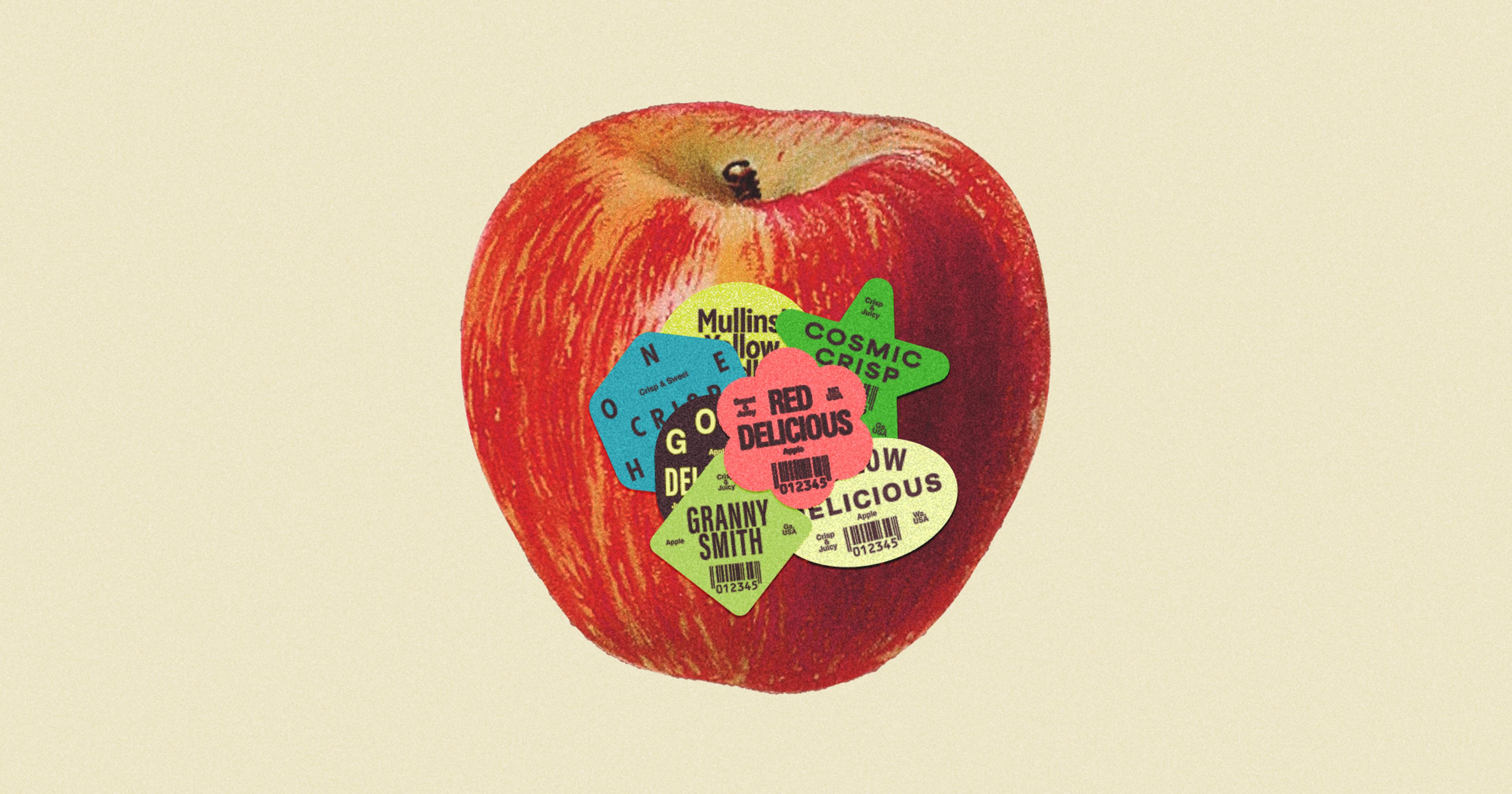

He’s right. They’re rich, buttery, and faintly sweet, with a depth of flavor absent in shelled, months-old grocery store varieties. His breeding program is first and foremost about blight resistance, but it’s about more than that, too. Molnar wants to identify and propagate trees that will yield impressive quantities of round, flavorful, hefty kernels that shed their skins when roasted, so they can be inserted into chocolate bars, sprinkled into salads, blended into butter, or eaten by the handful.

He points to a Raritan — a robust cultivar he calls the “workhorse” in his stable — with admiration. When its nuts are roasted, he said with pride, “they just unzip.” Named for the river that runs alongside Rutgers’ campus, it’s joined by the Monmouth, Somerset, and Hunterdon (the New Jersey counties where they’re being grown), as well as the Beast, a pollinizer that earned its moniker by towering over smaller, weaker plants in research trials. (Hazelnuts are wind-pollinated and unable to fertilize their own flowers, so trees like the Beast are needed to produce nuts.) As a group, these trees are the first that a farmer in the region could reliably plant in the European hazelnut’s ideal growing range — throughout the Mid-Atlantic and reaching into southern Ontario and parts of Michigan — without fear of ruination.

Getting here has been slow work. It takes 17 years from the time two parent plants are bred until a hazelnut cultivar can be released. Today, Molnar’s research farm is full of healthy green trees studded with clusters of nuts ready to drop, but as recently as seven or eight years ago it was a different story. “When I brought people here,” he said, “it was just dead and dying trees every year. It looked like hell.”

“When I brought people here, it was just dead and dying trees every year. It looked like hell.”

For Molnar, trees have been a lifelong companion. Much of his childhood was spent exploring the woods of eastern Pennsylvania, where he moved when he was nine. At home, his yard was full of ornamentals from the nursery where his grandfather, mother, and uncles worked. (In addition to hazelnuts, he also breeds dogwoods.) He always knew he wanted to be a scientist, someone who could make an impact on the world. Studying plants seemed more welcoming than research on animals, so he went to Indiana University of Pennsylvania to study plant biology. In need of a summer job after his freshman year, his aunt connected him with Reed Funk, Rutgers’ renowned turf grass breeder, who was turning his attention toward nut trees as he aged. Molnar planted his first hazelnut when he was 18.

He was taken by the work — the interaction with plant life and all the questions waiting to be answered. If he wanted to make a contribution, developing a sustainable, climate-friendly food source was about as good as he could do. He eventually transferred to Rutgers in the late 1990s and stayed on for a PhD under the mentorship of Funk, who gave him the program’s reins upon retirement. He narrowed his attention to the hazelnut, casting aside research on pecans, hickories, and chestnuts, because it offered a tangible problem to solve: With blight resistance, an industry could prosper. He only had to look to Oregon for proof.

A Valley Under Attack

North America is home to its own species of wild hazelnut, Corylus americana, but its small kernels aren’t viable in a market dominated by the domesticated European variety, first introduced to the U.S. by pioneering California nurseryman Felix Gillet in the late 19th century. The European hazelnut soon found a home in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, where the crop is worth over $120 million today, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But given its susceptibility to EFB, which is native to eastern North America, it wouldn’t exist at all without an effort similar to the one Molnar has undertaken.

Sometime in the 1960s, a single strain of the blight was transported west of the Rockies, where it had never been. (East of the Rockies, numerous strains exist, increasing the threat to susceptible trees and complicating the search for resistance.) By the ’80s it was traveling two miles per year, right through the heart of Willamette Valley. Orchards were decimated; the industry’s destruction seemed all but certain. But there was one species that could survive contact with EFB. Known as Gasaway, that species, identified in 1975 by a breeding program at Oregon State University, was a pollinizer — it carried small nuts in paltry quantities. But if crossed with more compelling trees, the resistance carried in its genes could make it a savior.

Mehlenbacher has led Oregon State’s program since 1986. A straight talker with gray hair and a thick mustache who got his start breeding fruit trees at Rutgers, he and Molnar have collaborated for many years, sharing research and plant materials in search of high-quality sources of resistance. That work has taken them around the world to collect germplasm from Turkey and a long list of former Soviet nations, in search of species that might carry resistance to EFB.

With Gasaway and the seeds he and Molnar brought back from those expeditions, Mehlenbacher bred enough resistant cultivars — 28 and counting — to replant the Willamette Valley and refortify Oregon’s hazelnut industry. Acreage has more than tripled in the past 15 years. But, he points out, “we don’t consider that problem solved.” This spring, an apparent mutation in the blight showed why.

When they heard rumors of EFB in an orchard at the northern end of the Willamette Valley, Mehlenbacher and his colleagues went out to inspect. What they saw was distressing. The pathogen had overcome resistance. Based on the size and position of the cankers, it had been seven years since infection — enough time for it to have spread considerably. And because the industry was now relying on Gasaway to breed resistance into each new cultivar, the entire valley was in danger.

“They all have the Gasaway resistance gene,” Mehlenbacher said. “That’s the scary part.”

There are ways to manage infected trees: scouting to catch it early, pruning, spraying fungicides. But many Willamette Valley growers are relative newcomers who thought EFB was vanquished and never learned how to handle it. Even worse, when demand dropped for the relevant fungicides, so did supply.

“People were a little bit complacent about the strength of that resistance gene,” Mehlenbacher said, “to the point where they weren’t doing any EFB management at all.”

It isn’t all doom and gloom, Mehlenbacher said, but overcoming the outbreak will take education, outreach, and more plant breeding to give farmers alternatives.

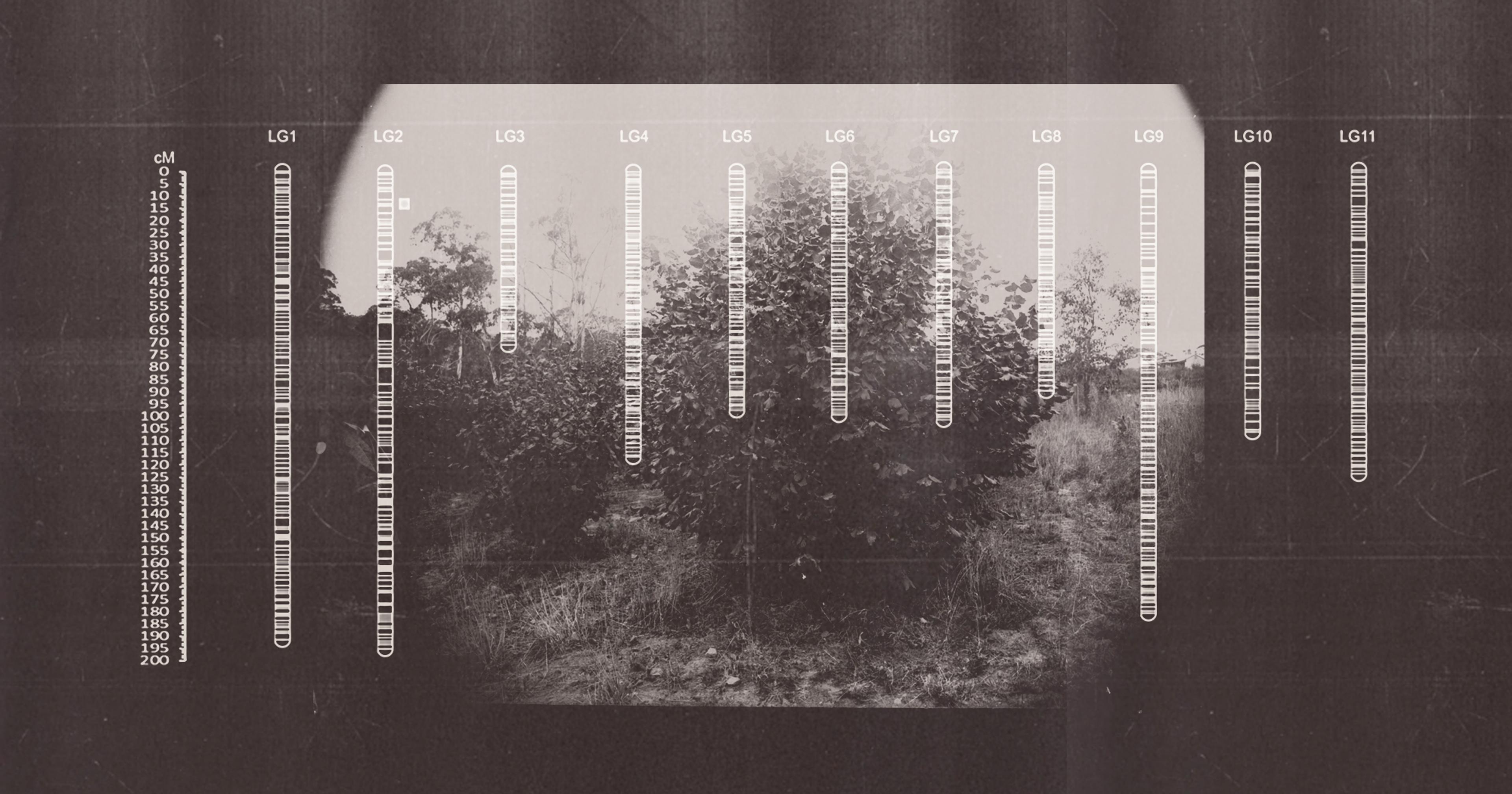

Mehlenbacher and Molnar are focused not just on genetic resistance, but tolerance — genes that can limit canker growth or spore spread, or allow a tree to keep fruiting even once infected. Combining those genes in new cultivars could create what they call “quantitative resistance” that would be harder for EFB to overcome. Where once Gasaway stood alone, they have now identified more than 100 major sources of resistance and nearly as many that offer quantitative protection. Still, the outbreak in Oregon is “a wake-up call,” Molnar said.

In addition to breeding with European varieties, Molnar and Mehlenbacher have crossed avellana with americana from the beginning, blending the superior size and quality of the former with the cold hardiness and EFB tolerance of the latter. (The Beast, for example, is one-quarter American, and boasts the native plant’s sticky husks as part of its genetic legacy.) The process of breeding hybrid hazelnuts moves slowly because of the generations needed to weed out the native plant’s inferior traits, including its small kernels and thick shells. But while his recently released cultivars are fully European, Molnar believes the American variety will figure prominently into long-term, sustainable hazelnut production in a changing climate. Sections of his research farm are devoted to the effort, in collaboration with the Upper Midwest Hazelnut Development Initiative, which is breeding native cultivars in hopes of kickstarting commercial production in the region.

“You don’t need 1,000 acres of this to have a good life for yourself.”

Jason Fischbach, a co-leader of the initiative, is tired of “the inertia of corn and soy” that holds sway in the upper Midwest. It’s all he sees when he drives around the region, he said, while the American hazelnut — native to the Midwest and nearly the entire country east of the Rockies — is relegated to the woods. “It’s a biological treasure,” he said, “but no one’s ever looked at it.”

There’s a small community of growers in the Midwest, Fischbach said, although none are yet using the American hazelnuts his program has been breeding. They’re interested, though, in an alternative to the corn-and-soy paradigm that could actually have a positive effect on the environment.

“We really are trying to take a whole new approach to what ails us agriculturally,” Fischbach said.

In on the Ground Floor

On his farm in Somerset, New Jersey, Ed Clerico is trying to do something similar. He grew up here in a family of dairy farmers that eventually transitioned to hay and beef. When his father died in 2013, he took over with an interest in something more sustainable. Exploring his permaculture options, he found Molnar and his hazelnuts. They were his favorite nut to crack as a kid, he said, and soon enough he was planting some of Molnar’s trees.

He’s now up to four acres, with plans to add two more per year. Last year was his first harvest, 300 pounds of nuts that he ground and baked into cookies, sold at farmer’s markets, and offered to chocolatiers as samples. “We weren’t shooting for the moon,” he acknowledged while rolling a handheld gatherer along the grass to pick up the first nuts from a harvest he expects will be closer to 1,000 pounds this year. Once the orchard fills out, he wants to establish a you-pick arrangement to help teach people about regenerative agriculture. He sees a bright future, both for the land that carries his hazelnuts and the industry Molnar is working to kickstart.

“You don’t need 1,000 acres of this to have a good life for yourself,” Clerico said.

From a farmer’s perspective, hazelnuts have plenty to offer. They require fewer inputs than a fruit crop like peaches or apples — less sprays, less labor to prune and train, and no need for hand-harvesting. The nuts simply fall to the orchard floor and wait to be swept up. One or two people can easily manage 50 acres, Mehlenbacher said, and the work can largely be done on the side of something else. In the shell, the nuts maintain quality for up to a year, so the season isn’t limited. And in the Mid-Atlantic, at least, there’s no competition to keep prices low.

Chefs and candy makers see the promise, too. Molnar’s hazelnuts are regularly featured at Blue Hill at Stone Barns, Dan Barber’s revered Hudson Valley restaurant at the agricultural vanguard. Molnar also has a longstanding relationship with Ferrero, which makes Nutella and is a dominant force in the global hazelnut industry. The company has helped fund his research, recognizing that although EFB is limited to North America, it could threaten hazelnuts worldwide if that changed. In that scenario, resistant cultivars would be vital. In the meantime, the company, always in need of nuts, is tracking the quality and output of Molnar’s cultivars.

Dan Richer, a James Beard nominee at Jersey City pizzeria Razza, got connected to Molnar 13 years ago while searching for local ingredients for his pies. He started with a five-pound bag and ample curiosity; these days, he buys a few hundred pounds from Rutgers each year to use on Project Hazelnut, a pizza he said has “a cult-like following.” It’s simple: fresh mozzarella, ricotta, a drizzle of honey, and hazelnuts — the star of the show. For Richer, the pizza is a platform to help diners discover something new about their region, and a way to support a nascent crop in the land of blueberries, cranberries, and tomatoes.

“I want to be part of a hazelnut industry developing in an area where it has such great possibilities,” Richer said. “It takes a village to accomplish these things.”

As soon as Rutgers released its cultivars in 2020, he planted three trees of his own. They haven’t fruited yet — it takes five years — but he appreciates them all the same.

“Every time I look at them I think of Tom, I think of New Jersey, and I think of my restaurant,” Richer said. “These trees in my backyard are part of something special.”

A Field in East Brunswick

In both plant breeding and tree crops, patience is a virtue. Although Molnar’s excitement about reaching this point is palpable, he realizes the finish line isn’t in sight. After all this time, he’s just settling into the starting blocks. In the next few years, he expects hazelnut acreage in the region to approach 500. Once the first wave — those trees already in the ground — begin producing mature harvests, he said, further investment will likely follow.

Slow growth is ideal, Molnar said. He doesn’t want his hazelnuts to be planted like they are in Oregon, where orchards often span more than 1,000 acres. “To be safe and buffered from the crazy climate,” he said, “we’re going to need this to be part of a diversified farm system.”

Even discussing these practical considerations would have been foolish earlier in his career, but it’s quickly becoming real. What he saw in George Dickum’s orchard all those years ago was a mirage of sorts, but the trees on Ed Clerico’s farm are built to last. It’s enough to make Molnar a bit reflective.

“In the plant sciences,” he said, “there are very few opportunities to do something like this with your career.”

He could be forgiven for getting a little emotional at the sight of a successful harvest. He’s seen whole progenies collapse, only to plant more. He’s known some of his trees longer than his own children. Many will end up outliving him. Someday, if he has his way, his grandkids will be able to pick up a hazelnut and trace its history back to a field in East Brunswick.

“I guess it’s a fear of the shortness of life that has always driven me,” Molnar said. “If you have the opportunity to make a contribution, you have to do it.”