Research and funding partners have now pulled support for the Darling line of transgenic trees, a significant setback for restoration plans.

In the 19th century, across 320 million forest acres from southern Maine to central Mississippi, springtime brought the flowering of pollen-coated catkin clusters on billions of American chestnut trees. “Visually, the trees were a sight to behold, turning entire mountainsides a creamy yellow and then, as the catkins began to release their pollen, a sugary white that from a distance resembled snow,” wrote Donald Davis in his 2021 environmental history of the tree, The American Chestnut.

That “glorious” sight, and the ecological, cultural, practical, and financial benefits it heralded — food for humans, wildlife, and livestock; wood for houses, fences and railway ties; extract for tanning leather; an important feature in Native creation stories — was all but extinguished by a fungal blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, by the early 1900s. Biologist James Hill Craddock called the loss of 5 billion trees and their 2 billion tons of biomass the “greatest ecological catastrophe since the last Ice Age.” It increased carbon levels, helped push some woodland species closer to extinction, and deprived waterways of the trees’ cooling powers.

For decades, scientists have been toiling to make a blight-resistant American chestnut tree. One prominent project, of the State University of New York’s College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF), was showing great promise in developing a genetically modified tree — until that effort suddenly unraveled.

This past December SUNY admitted a major error with a variant known as Darling 58. This caused its research and financial partner, the American Chestnut Foundation (TACF), to pull its support of D58; skeptics to opine about the futility of restoration efforts; and critics to clamor about allegedly nefarious aims by the researchers. Indigenous groups especially have opposed GM trees as an infringement of their food sovereignty. The ensuing brouhaha “highlights the challenges of understanding the impacts of introducing long-lived organisms into the wild,” according to a press release from the Campaign to Stop GE Trees.

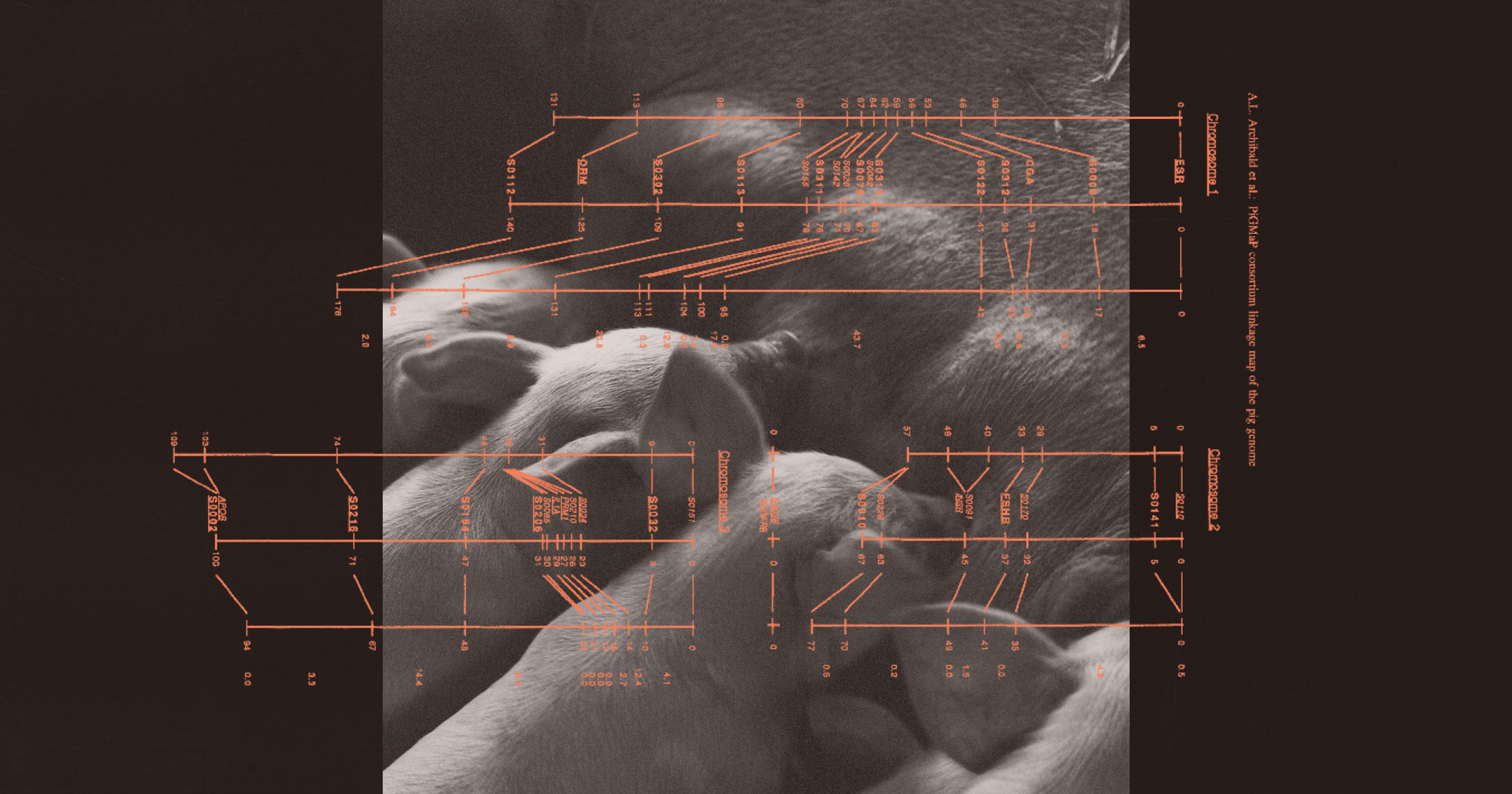

There are three distinct methods to pursuing a blight-resistant American chestnut. One, used by the American Chestnut Cooperators’ Foundation, seeks to breed resistance into 100 percent American chestnut trees. Another, undertaken by the American Chestnut Foundation (TACF), is a backcross in which American chestnuts are cross-bred over and over with Chinese chestnuts to impart the latter’s blight tolerance into a hybrid tree. The third — and most controversial — is genetic modification. SUNY inserted a wheat enzyme called oxalate oxidase, or OxO, into a chestnut that’s grown to a seedling in a lab. Then that seedling is used to pollinate wild trees whose progeny carry the OxO that can set off blight resistance.

“It’s not that the mistake was made, it’s that we weren’t told about it.”

After years of fiddling, SUNY put the first transgenic chestnut trees in the ground in 2006; there are now thousands of younger trees planted under permit in several locations. In 2019, SUNY considered the project sufficiently robust to file a petition with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal & Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), to have D58 deregulated. If approved, this would theoretically make the trees available for distribution to the public.

Just as everyone was checking their watches and imagining federal approval must be imminent, in early December 2023 it was disclosed that SUNY had goofed up variations of its breeding line. Instead of using D58 to pollinate trees in its research plots, it had accidentally used D54, which has OxO DNA inserted into a different part of its genome; almost all those thousands of transgenic trees are D54s, not D58s. Newhouse insists it’s not a big deal, equating the different position of OxO to a word in a novel that’s turned up in one chapter instead of another. “They’re all the same phenotype. They all have the same new DNA. It’s not a mix of genes or a bunch of unknowns,” he said.

TACF, though, withdrew its support of the APHIS petition and the trees themselves, saying they’d already noticed “disappointing performance results” and expressing irritation they’d learned about the gaffe from researchers in Maine rather than from SUNY. “It’s not that the mistake was made,” they told The Washington Post. “It’s that we weren’t told about it.” APHIS put the petition on pause so SUNY could present additional details about D54; it was apparently reviewing these details at the time this story was written.

Regardless of which breeding line is listed in the petition, Davis thinks they’re equally problematic. In both, the OxO gene “is constantly turned on, and that means all their energy is going towards fighting blight as opposed to growing the tree,” he explained. As a result, trees grew stunted and covered in cankers. He speculates that the D54 mix-up was a convenient excuse for TACF to withdraw its support because there’s another breeding line in the works, called win3.12, whose blight-resisting powers are only activated when it comes in contact with Cryphonectria parasitica. But Davis also calls this maneuvering “bad poker”: Approval for the Darling lines would grant approval for win3.12 and any other transgenic chestnuts containing OxO — so why push back?

“Even people who used to be fans of the American chestnut would say it had its chance, it had its place in history.”

He sees other problems with the GM restoration endeavor. Though most of the 430 million American chestnuts growing wild today succumb to blight before they mature, there are full-grown trees that have somehow avoided this fate. So far, the transgenic American chestnuts that cross-pollinate with wild trees pass down their blight resistance only 50 percent of the time, and they’re also susceptible to other blights. That means, were they to cross-pollinate with still un-blighted trees, it could wreak havoc on remnant populations, making them extinct once and for all.

Additionally, the transgenic trees have only been tested for blight resistance for a few years. “Baby trees are not the same as 200-year-old trees,” said Rachel Smolker, co-director of renewable energy nonprofit Biofuelwatch, and as they age, they might begin to show less resistance, or other negative traits. “We know that an organism’s genomes behave differently at different stages of life and with exposure to different environments, and that there’s no way that just testing baby trees that have been grown in controlled conditions proves anything to us whatsoever,” Smolker said. Biofuelwatch believes the biotech industry has been quietly supporting transgenic chestnut efforts in order to soften public opinion for plantations full of (still elusive) transgenic pines and poplars — these in the pursuit of liquid biofuels made from wood.

While chestnut blight may have been the nail in the coffin for the American chestnut, the tree had other problems before the fungus arrived on imported Japanese trees. One was ink disease, Phytophthora cinnamomi, which wiped out chestnuts in the southern part of their range by the Civil War; it can’t survive the cold but could move north with climate change. The transgenic trees are not currently resistant to ink disease; at least one backcross breeder, though, has focused on making chestnuts resistant to more than one disease.

Not that hybrids are a faultless alternative to transgenics. “There are lots of exotic varieties of plants that have been hybridized that are really vulnerable to pests, and then they introduced a pest to a native species. So that’s not benign either,” said Smolker.

The restoration challenges are so steep that “even people who used to be fans of the American chestnut would say it had its chance, it had its place in history,” said Davis. “They say now we need to move on to species that are going to be more likely to survive in new environmental conditions.” In the moment, a blight-resistant American chestnut of any sort seems a long way off, despite the anticipation of its potential revival.

Note — After this story published, Ed Greenwell, president of the American Chestnut Cooperators’ Foundation, wrote in with this information:

We have been successful in breeding trees with durable blight resistance/control. Our oldest trees were planted in 1976, so are coming up on 50 years. Perhaps another point of significance is that our program has bred five generations of pure American chestnuts that show durable blight resistance. Many of these trees are growing upwards of 60 feet tall, are nut producing and exhibit excellent blight canker response.