As the Trump Administration’s trade war with China continues, soybean farmers wonder who will buy their crop.

Like many U.S. farmers right now, Paul Overby is feeling the Big Tariff Squeeze. For starters, the early August tariffs the Trump administration socked on an enormous swath of countries, including some input producers, raised fertilizer costs for the North Dakota commodity and specialty crop grower. A high Chinese tariff on canola from top producer Canada, affects U.S. farmers, too, whose prices are tied to those of our neighbor to the north; this leaves Overby with an as-yet untallied loss on this year’s harvest. And as of this writing, not a single soybean shipment had been booked from the West Coast to leading importer China, as that country retaliates for a U.S. tariff on all Chinese goods and Trump threatens to push it ever higher.

“We’re just struggling to deal with the normal fundamentals of the market — supply and demand — then there’s this whole uncertainty that’s created in the marketplace because of the craziness of tariff threats and then next week it’s different,” Overby said with an air of exasperation. “Just like the grocery store, once the prices go up, they don’t come down very fast,” he pointed out. Nevertheless, “We can’t do anything about it so most farmers are ignoring it for now, putting their heads down like, ‘Harvest is coming, I just gotta get the grain in the bin.’”

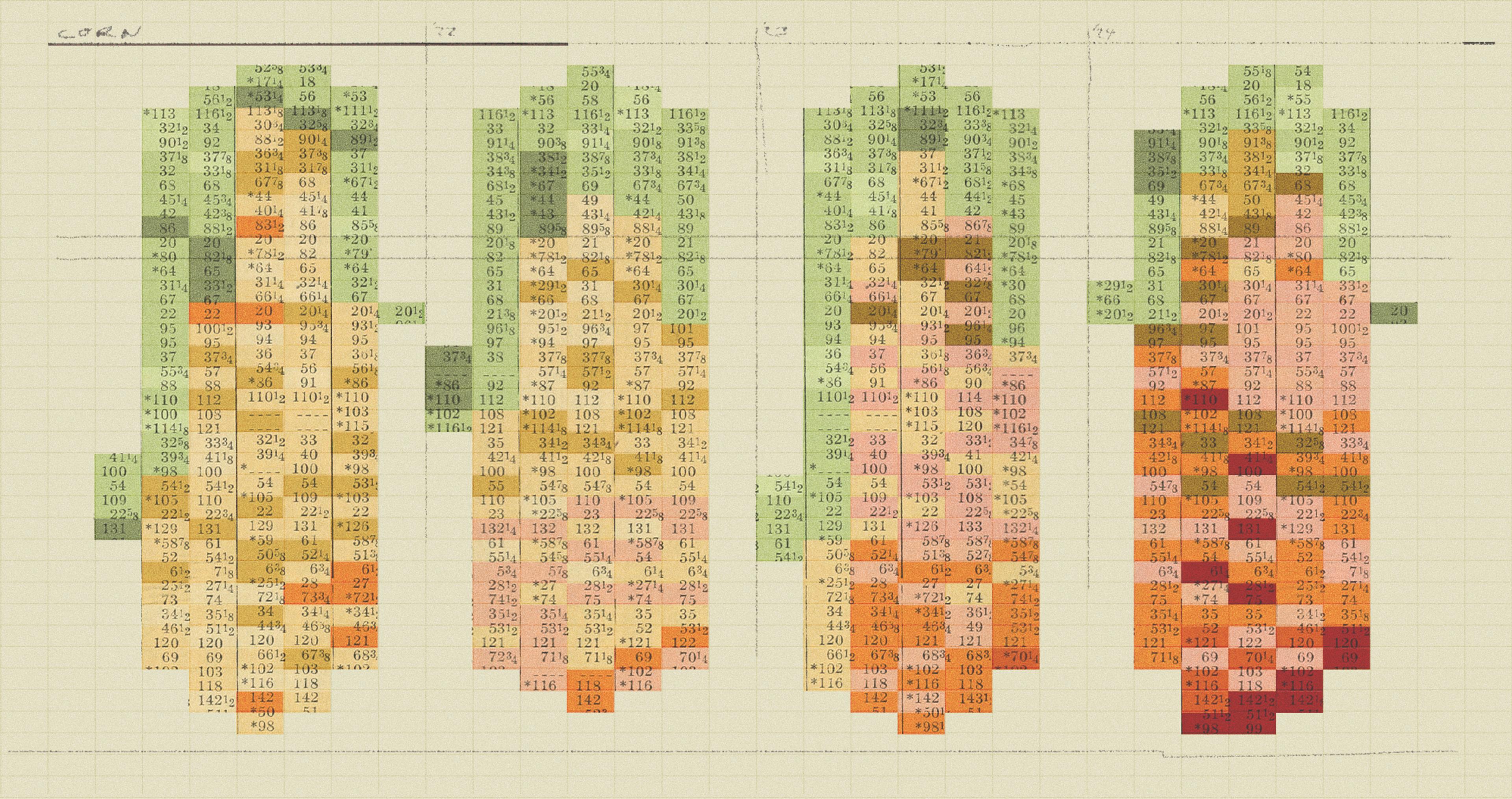

The U.S. harvested 4.36 billion bushels of soybeans last year, and more than half of that windfall shipped to China. Where the brunt of this year’s haul will go is — thanks to that essential trading partner’s decision to purchase zero American soybeans in retaliation for a 56.7 percent tariff on all Chinese goods — a matter of growing concern. And it’s happening just as U.S. farmers are bringing in their beans; the season for exports is September to February, with a slight overlap with when South American soybeans mature and hit the market, according to Mike Steenhoek, executive director of industry group the Soy Transportation Coalition, who grew up in an ag family.

Steenhoek compares the yanking of the Chinese market to a restaurateur who opens a sports bar next to a major league baseball stadium, where customers are almost guaranteed — only to have that team pick up and move to another city. “Someone can say, there are other customers out there; you can diversify, and we have been working very diligently to achieve that,” Steenhoek said. “But we’ve had this very mutually beneficial relationship with China for years and it’s served farmers well and been a source of major rural economic development.”

“We can’t do anything about it so most farmers are ignoring it for now, putting their heads down like, ‘Harvest is coming, I just gotta get the grain in the bin.’”

Suddenly needing to find an outlet for $13.2 billion worth of soybeans — the amount China purchased last year, compared to the $2.3 billion purchased by number two importer Mexico — is no easy lift. Not least, said Steenhoek, because China is the ideal soybean customer: a country with a large population; growing per-capita income to spend on food; an “insatiable demand for pork … and poultry” (hogs and chickens are the livestock fed the most soy meal); and a lot of home cooks who stock soy oil in their kitchens. “There isn’t another country that would have all those bullet points,” Steenhoek said. “That’s why it’s a real concern.” Not to mention, China has begun to invest in Brazilian soybeans, sending the clear message that “the United States is going to become [their] supplier of last resort,” Overby said.

As a result, the price for U.S. soybeans is now so low that grain elevators are sending letters to farmers, warning of the challenges to off-loading them. “At present, selling a soybean train is nearly impossible, and with the export market essentially at a standstill, we do not know when trading conditions will improve,” wrote grain cooperative CenDak to its members on August 18, in correspondence shared with Offrange. And the American Soybean Association, an industry trade organization, penned a letter to the White House on August 19, warning that “soybean farmers are standing on a financial precipice,” and urging the administration to prioritize their needs in upcoming negotiations.

What Overby called the “Trump tariff thing” was also an issue back in 2018, during his first presidential term. Crop prices had just plummeted and those tariffs “did not help anything at all,” Overby said. But biofuels, which can be made of corn, soy, and other grains, helped pull prices back up under Biden; exports mostly snapped back towards normal-ish, Steenhoek said.

“At present, selling a soybean train is nearly impossible, and with the export market essentially at a standstill, we do not know when trading conditions will improve.”

In a normal-ish export year, Midwestern soybeans get barged down the Mississippi, Ohio, and Illinois rivers to export facilities in New Orleans. Meanwhile, hundred-car-long trains shuttle soybeans from Western states to Pacific ports, and Pacific Northwest beans get barged down the Columbia River or through the Puget Sound. In Memphis, the main port for Arkansas growers, “There’s no [grain] barge traffic on the Mississippi River,” farmer Shawn Peebles told Offrange on August 19, recounting his first-hand view of the scene. “I mean, that’s scary. That is something I’ve never seen. I’m 54 and I have never seen it this bad. Would this put me out of business? No. Could we lose all our retirement? Yeah, yes.” (There has been some grain barge traffic elsewhere on the Mississippi but it’s down from last year at this time.)

Members of Overby’s wife’s book club had recently mused that grain elevators might not even purchase farmers’ soybeans this year — a rumor Overby’s co-op has since dispelled. “There will not be turning away of soybeans at elevators,” confirmed University of Illinois farm economy professor Gary Schnitke to Offrange in an email. “The question will be the price.” Not to mention how long the beans will have to sit around before it’s worthwhile to sell them.

That wait causes at least one serious ripple effect: “There’s going to be a lot of bushels that are going to need a home and then when you don’t have a green light for our major international customer, that’s going to put pressure on storage,” Steenhoek said. Dried soybeans can store for a couple of years, even in piles on the ground. But a soybean surplus from 2024 means some farmers have “missed the opportunity to pull the trigger” and sell off last year’s crop before this year’s harvest, Steenhoek said. Worst-case scenario: They’ll have to continue to pay for storage even as Brazilian soybeans start flooding the market in a few months, further limiting demand for the U.S. supply. Peebles responded to this possibility with resignation. “We’re approaching everything as business as usual, because you don’t have a choice, really,” he said.

Steenhoek said the landscape is not all doom and gloom, though. For starters, “Increased low prices will result in increased demand elsewhere, and we will continue to pick up [other] sales.” (He declined to say where.) A decrease in the value of the U.S. dollar will also help make exports more competitive, he predicted.

“I’m 54 and I have never seen it this bad. Would this put me out of business? No. Could we lose all our retirement? Yeah, yes.”

He and Overby are also both counting on a lift from the renewable fuels market, which can use any number of crops to make biofuel, including soybeans. “Delta Air Lines is buying every gallon they can get of it, because of the regulation in Europe requiring international flights … to have sustainable fuel,” Overby said. “Just like the farm crisis in the 2000s, which we solved by turning corn into an energy crop, that’s, in essence, what we’re probably going to do now — turn soybeans and some other minor crops into energy as a way of providing a support base for farmers.” Steenhoek said that the U.S. is currently limiting imports of renewable fuel feedstocks from other countries, “So that is certainly helping” soybean farmers, he said. Where soybean meal (as opposed to oil) can be sold, though, remains an open question, as does how the transportation industry will weather this swift change in supply chains. “It really wreaks havoc,” Steenhoek said.

The American Soybean Association has pleaded with the Trump administration to get China to remove their retaliatory tariffs and commit to a “significant” soybean purchase. There was no movement on that front in early September, although a Chinese ag consultant told Reuters that things could change come November, with the cost of U.S. soybeans “attractively priced” (read: low) and Brazilian beans priced high.

Still, Overby’s not overly optimistic about how things will pan out. “Those of us sitting in the middle with these smaller size operations are the ones that really get squeezed,” he said about his 1,300-crop-acre operation. “We’re too big to go get a bunch of off-farm income, and yet we’re too small, from a capital standpoint, to have a huge amount of resources to dip into to ride it through. That’s really the hidden farm crisis.”